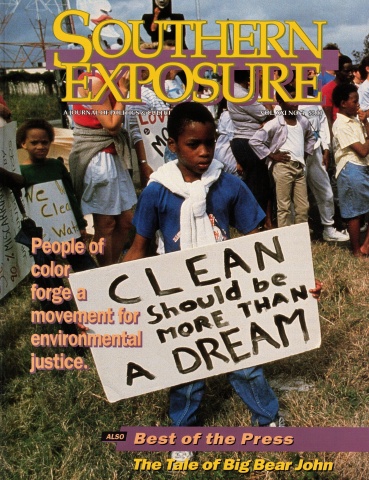

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

MURFREESBORO, TENN. - Pat Floyd worked the swing shift at General Electric for 12 years, earning $9.95 an hour to clean the bonding oven where freshly lacquered motor windings were baked dry. She used solvent and thinners to scrub the oven walls, and the company provided a vapor mask, gloves, and an exhaust fan for her protection.

Last spring, GE closed up shop in Murfreesboro and moved to Juarez, Mexico. The workers who replaced Floyd receive only $1.11 an hour, and the company provides no safety equipment- only the solvent and thinners. After less than a year on the job, Mexican workers complain of nausea, dizziness, and loss of appetite.

Since 1982, more than 5,000 Tennesseans have lost their jobs to Mexico. U.S. companies now run more than 2,000 assembly plants known as maquiladoras along the border from Brownsville, Texas to Tijuana, Mexico, taking advantage of the same kind of low wages, unorganized labor, and weak environmental regulations that have long made the American South a profitable place to pollute.

"Corporations are going south, whether it's from Tennessee to Texas or Texas to Mexico," says Ruben Solis of the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice in San Antonio. "They go to places where they can take advantage of people. They look for communities that do not have a position of power, so there's no enforcement of regulations."

Between 1986 and 1991, Mexican jobs created by multinational corporations rose by 25 percent. Most of the work involves auto production and electronics, but low-skill, labor-intensive Southern industries such as textiles and food processing are also starting to cross the border. Maquiladoras operate in duty-free zones on the border, where they import raw and unfinished goods into Mexico and ship finished products back to U.S. markets with few or no tariffs.

The much-discussed North American Free Trade Agreement- better known as NAFTA- is designed to greatly expand these zones. The agreement will create an international tribunal of "trade experts" with the legal power to eliminate state or local environmental, health, safety, and labor laws it deemed "trade barriers." Side agreements call for separate panels to monitor environmental and labor standards, but left the powers of the tribunal intact.

Despite the environmental risks, major environmental groups like the National Audubon Society and National Wildlife Federation rallied support for the agreement. Corporate executives from WMX, the largest waste management company in the world, sit on the boards of both groups. Ignoring opposition from many of their local and state chapters, the two organizations joined with USA*NAFTA, a coalition of more than 400 multinational corporations including WMX, GE, Du Pont, Eastman Kodak, Citicorp, and American Express that committed to raise $2 million for a pro-NAFTA lobbying and public relations campaign.

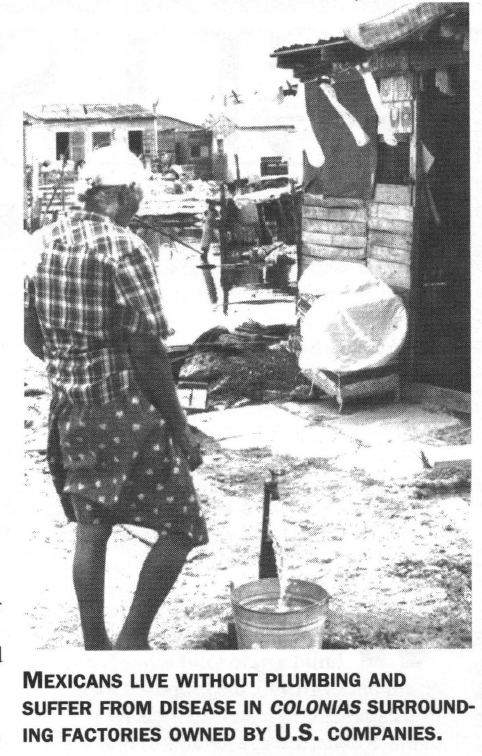

Under NAFT A, corporate giants will increase their push south, paying people of color to perform dangerous jobs and dumping hazardous waste in their communities. More than six million people now live along the 800-mile industrial corridor between Texas and Mexico, many inhabiting the unincorporated communities known as colonias that have sprung up around the maquiladoras. Most colonias have no potable water or sewage systems; many lack electricity.

To make matters worse, 25 years of unrestricted dumping by the maquilas has resulted in a health crisis. A survey of water and soil by the National Toxics Campaign documented “an alphabet soup of toxic chemicals” along the border. An alarming number of babies have been born with partial or missing brains or spinal cords, and adults suffer from tuberculosis, typhoid, hepatitis, and cholera as a result of poor sanitation. Cervical cancer among women is three times the rate of U.S. women, and bladder, liver, and bowel cancer are common.

Many U.S. communities abandoned in the rush to Mexico also suffer from a legacy of pollution. Alco Pacifico operates a lead smelter in Tijuana, Mexico after closing a smelter that poisoned a black and Latino community in Dallas, Texas. Schlage Lock left behind a toxic Superfund site and hundreds of unemployed workers, many suffering from respiratory problems and eye irritations, when it closed its doors in Rocky Mount, North Carolina and moved to Tecate, Mexico in 1988.

As companies cross the border, workers are also forging international connections. Joan Sharpe, a former Schlage worker and an organizer with Black Workers for Justice, visited Tecate to see conditions for herself. In the colonia surrounding the plant, she met teenaged women who worked 10 hours a day for $4.

But when Sharpe asked to talk to workers inside the plant, managers refused to let her in. “I could point out areas that were real hazardous,” she says. “They didn’t want me to have that kind of connection to workers.” Sharpe waited until workers came out on breaks and gave them flyers explaining why she was there. She also told them that the severe rashes on their hands came from the graphite they were working with on the job.

Conditions are bad, says Sharpe, and NAFTA would only make things worse. “It’s an open gate for plants to just pick up and leave without having to deal with anything.”

Across the region, grassroots organizers like Sharpe are working to improve conditions along the border .The Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras in San Antonio urges companies to abide by voluntary Standards of Conduct to control wages and benefits, environmental contamination, and health and safety. Such standards apparently threaten Mexican officials: The group is being investigated by the town of Matamoros, host of some of the worst maquiladoras.

“It’s important for people to realize that the ones who are being investigated and having the pressure put on them are not the corporations,” says Sister Susan Mika, who chairs the Coalition’s board. “It’s the people who are trying to document and expose what’s going on.”

The Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice took the lead in opposing NAFTA. Last July the network held a gathering in Tucson, Arizona, bringing together grassroots activists on both sides of the border to develop a common agenda. One concrete result was a series of protests held along the border in October in collaboration with the Red Mexicana Frente al Tratado de Libre Comercio (Network to Stop NAFTA in Mexico).

Opposition to the accord also forged important links between environmental and labor organizers. For years, companies have pitted workers against environmentalists, claiming that stiff "green regulations" threaten jobs. But some of the largest labor unions initiated active anti-NAFTA campaigns - citing the threat to the environment as a primary concern.

"Health and safety and toxics are issues that more people have had to personally deal with than conservation," explains Bill Troy, director of the Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network in Knoxville. Since TIRN was organized in 1990 as a resource for workers threatened with plant closings, the group Photo by Ernesto Mora has developed a heightened awareness of environmental issues. TIRN created an educational program on the impact of free trade, and nine members traveled to Mexico to see conditions in the maquiladoras first-hand and share their experiences with workers back home.

"I saw children playing in green slime from chemical plants," says Shirley Reinhardt, who used to work in a GE plant that relocated to Mexico. "I thought I had seen everything, but I have never seen anything like this."

NAFTA opponents also united across racial lines. "Black workers are more likely to be employed in industries which will experience large job losses to Mexico," says William Lucy, Secretary-Treasurer of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees and president of Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. "If American business was making investments in our inner cities and poor rural communities, as it is doing in Mexico, black unemployment would plummet."

Native American organizers also fought the agreement. "It would have a tremendous impact on us, but no one is pointing out what the impact will be," says Jackie Warledo of the Indigenous Peoples Network.

Ruben Solis of the Southwest Network says that any trade agreement must include basic principles that will force industry to improve worker safety and wages, clean up existing pollution, and eventually eliminate toxics at the source of production. The Network also calls for including a declaration of human rights.

The key to dealing with the problems of free trade, says Solis, is to involve people who live and work in effected communities. "We have to begin with extensive hearings to let people speak about what has been happening for 25 years of industrial programs on the border. The people who have been contaminated have to have a voice in the process."

Tags

Rick Held

Rick Held is a journalist and activist based in Knoxville, Tennessee. (2000)

Rick Held is a writer in Knoxville, Tennessee. Ruben Solis, coordinator of the Border Campaign for the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice, contributed to this article. (1993)