This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

In October 1991, more than 600 grassroots leaders gathered for an historic meeting in Washington, D.C. They represented Latino, Native American, African American, Asian American, and Pacific Islander communities from across the United States and its territories.They had come to attend the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit.

The Summit was a defining moment in the emerging movement for environmental justice. After much discussion and debate, the delegates drafted 17 Principles of Environmental Justice that represent a radical departure from traditional views equating the environment with air, water, and land. The Principles redefined “environment” as “wherever we live, work, and play,” expanding the concept of environmental hazards to include unsafe jobs, unemployment, inadequate housing, poor health care and education, unresponsive government, police brutality, and crime.

The Summit transformed the participants, bringing in its wake a powerful surge of grassroots activism led by communities of color. In rural towns and inner-city neighborhoods across the South, activists are striving to do more than simply distribute pollution equally among all social groups—they seek ways to free all life from the burden of toxic contamination.

The Summit also altered the direction and priorities of predominantly white national environmental organizations and government agencies. “Those of us who went to the Summit and saw the power, the courage, the knowledge, and the effectiveness of those 600 environmental leaders of color came away changed,” said Michael Fischer, former head of the Sierra Club. “The experience changed our lives, and the lives of our organizations.”

Two years after the Summit, however, it is clear that the environmental justice movement has fallen far short of the powerful promise evident at its birth. The movement has become a storm center of wrangling around issues of leadership, funding, and vision. There are increasingly rocky relations between people of color and whites, between grassroots groups and national organizations. The great unifying hope of the Summit is in danger of being lost.

This special section of Southern Exposure on environmental justice emerges from our concern for the future well-being of the movement and the suffering communities it seeks to heal. We hoped it would serve the interests of all concerned if we took an in-depth look at environmental justice work where it matters most — on the frontlines of community-level struggles.

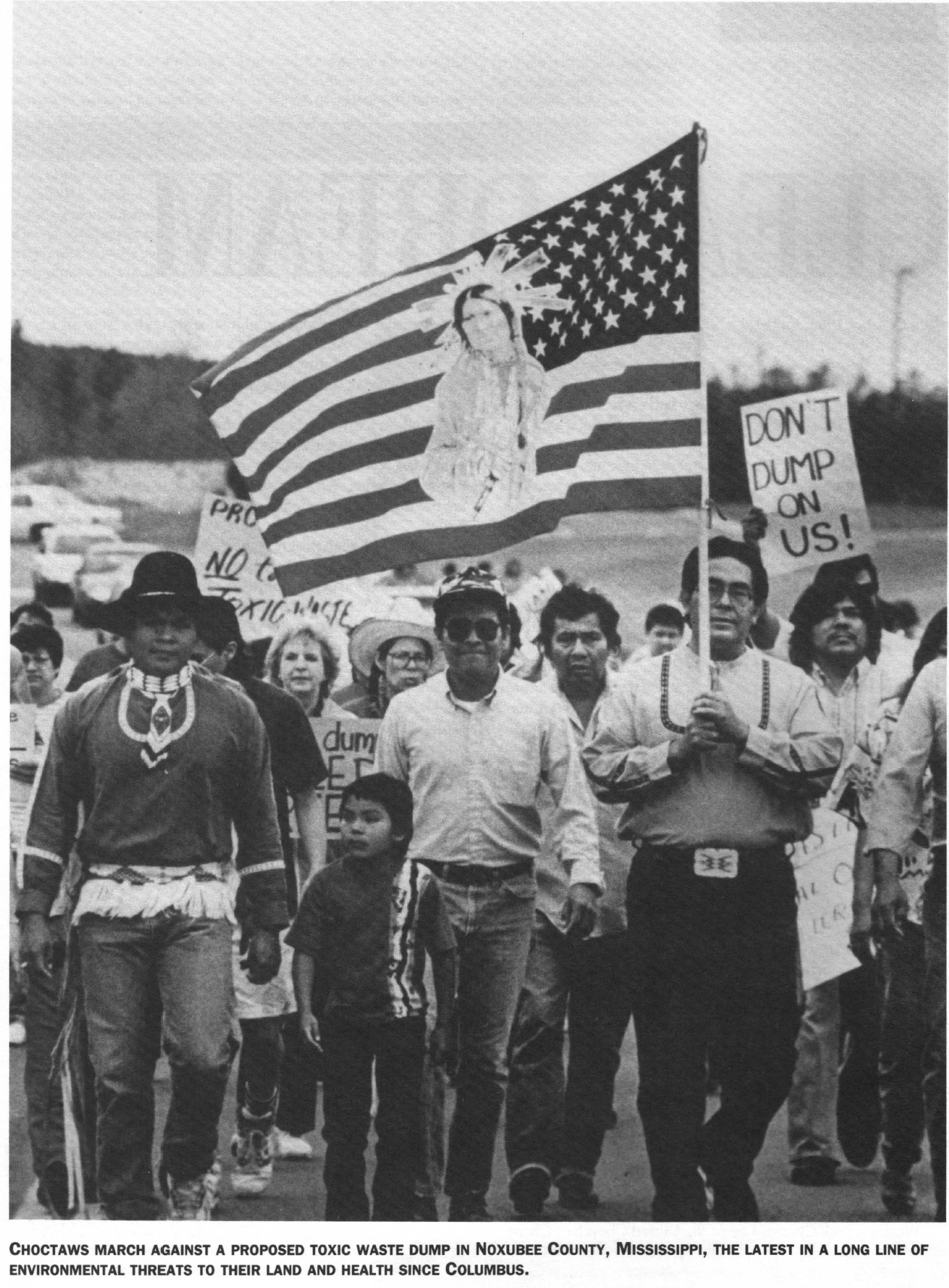

Working with Charles Lee of the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice, we put together an overview of environmental racism from Columbus to the present. We collected stories of environmental justice struggles from all 13 Southern states. And we invited a wide spectrum of local activists to discuss the future of the movement, share their experiences, and speak for themselves on the issues they care about most.

What we learned is both encouraging and discouraging. We are heartened that grassroots activism is on the rise, and that youth and workers are increasingly involved in environmental justice struggles. We are also glad that state and federal officials are paying more attention to environmental justice and equity issues.

But despite such progress, poisoning industries and waste facilities are escalating their assault against communities of color. Victimized communities are fighting for their lives with grossly insufficient resources; environmental justice groups find themselves in keen competition for diminishing financial support. And the pervasive climate of organizational turfism and racial polarization remains a powerful impediment to serious cooperative action.

These obstacles to united action require a refocusing of our efforts. The environmental justice movement recognizes that widespread environmental degradation is an inevitable outcome of our current mode of economic production. Until we adopt different ways of meeting our material needs, we will make no appreciable headway in reducing toxic contamination. In short, we must face a fundamental question: "What can we do to create a future for people of color and our society as a whole that is both economically viable and environmentally sustainable?"

If the environmental justice movement is to survive, we must strengthen the capacity of communities of color to develop meaningful economic alternatives to polluting industries and waste facilities. We must give serious and sustained attention to help communities develop their own leadership, raise money, build coalitions, and shape public policy. Only by placing community-based economic development at the center of our work can we hope to keep the environmental justice movement on the high road of inspired cooperation and constructive activity.

The diversity of agendas within the movement is a source of great strength - but it is also a source of conflict. Effective action requires coordination and cooperation. We in the movement must work to strengthen our unity of purpose and vision if we are to fully realize our dream of environmental justice for all.

Tags

Isaiah Madison

Isaiah Madison is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies. He became interested in community economic development when working as a lawyer in Mississippi. He handled cases for black farmers having difficulties holding onto their land and became involved with the Federation for Southern Cooperatives. (1994)

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)