Stick Woman

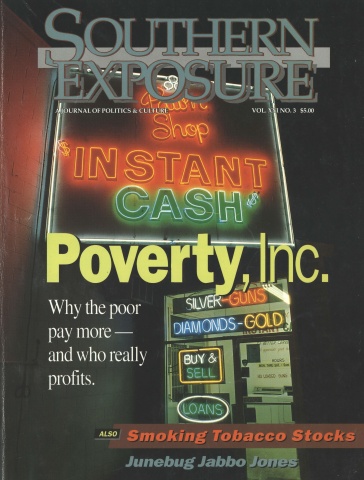

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

You have to know this I tell you.

Here is what I do have: I got a stick and I got legs to carry me to see my boy every week now. Used to be every day, but I gets tired nowadays. And they say, “Look at that fool woman!” I walk ten miles to the graveyard and ten miles back. The people along the way, I know they talks about me. I see their heads turning and their jaws working. I hear the whispers: “Shame . . . poor thing . . . lunatic woman.” They in my business, even white folks got a look in their eye for me when they see me coming. But ne’er one of them will stop and ask me why I hobble down this here sand road every week. Ne’er one of them don’t have to feel sorry for me neither. You neither . . . but you come to listen.

I know, I see, I hear — can you grant a poor old black woman that? Can you grant me, though I can’t read nor write, that I have birthed volumes of poetry as I breathe? But then all you can see is an old woman wrapped in rags that don’t match. I ain’t got no teeth and my hands are black and knotted like roots of some tree. And these hands dig deep — I got a stick.

You know, this dirt was always for my stick. The cemetery is on the road to Hamalata. All the colored boys was buried in the pasture there that belonged to some crackers before it did to the government up-North. And they marked Gabby’s grave like they did all the rest: with tin crosses. It took only a couple of rains and they, the crosses, began to rust. They was red in the red Georgia clay that was churned and blistered with sores that would be new graves, staved with some more bleeding crucifixes — in the clay and scattered with no sense, like weeds, like so many crumbling fence-posts lining a madman’s acre. Gabby’s cross, too. My boy’s head was under it, the cross. Six feet, as long as my stick, for twenty odd years. It was for the clay that I sharpened it. You know, I dig in the ground over his grave. I push the sharp stick down as hard as I can. And it got harder to do as time went on. The clay got harder and I got older, frailer. But I dig down, I testify! I dig a hole with my stick until I hit something solid that won’t give. That be Gabby, my boy, right under my stick. See? But in 20 years the hard thing gets deeper — through the clay, through the dirt. I push this stick through the unsapped wood that was his casket and then the bones and then back into the dirt. Stabbing Gabby’s grave. And I’d tap on his casket when it was there before it was dust. Everyday. Once a week now, I tap and feel connected through my stick to something. Down deep things wash back and forth like a tide. I remember having a little and then having nothing but memory that comes unstuck; like beads from a broken string in the dust and nonsense. Like me and my stick.

What for do I tell you these things?

Do you smell the honeysuckle? Lawd have mercy. Twenty years alone. Buster gone long before that. Buster, my man. You could smell the honeysuckle then — always that smell, sweeter than anything you can put in your mouth. Acidy, like it wants to burn your insides. But it hangs, that smell, swelling up in your throat and choking you the way tears do. Carry on. Carry on.

Buster was gone this time around, near about 35 years ago. Buster went, then Gabby — he gone too. My man and my boy. Losing this thing or that thing, they say. Lawd, you can lose your soul — is that not your teaching? And then you can be poor and lose everything like me, except your soul. Ain’t no consolation in this darkness, the darkness what the preacher pray over — an empty nothing — except what I put imagine to. Sweet Jesus can have that too, my soul.

Buster, my man, he was one of those Turks from up Georgetown way. They say the Turks come from over the water somewheres. They ain’t colored like the rest of the nigguhs that around up in the country or around here in DeRenne neither. Buster was one of them Turks for sure he was tall, slender, red-color-brown like ginger. His nice hair, it was that ginger color too. His eyes: they was dark in a way that didn’t go along with the rest of him. They was wild eyes. And let me tell you, when me and my girlfriend seen him for the first time on the excursion boat, out Daufuskie way, she say, “Chile, you better grab that pretty man before them high-yallah gals do.” And I say to myself: I ain’t studyin’ him. I ain’t looking for no man nohow.

But I seen all the high-yallahs, them teachers’, preachers’ and undertakers’ gals just rolling they eyes at him and switching cross the deck like they was August she-dogs and I say to myself: “I’m gonna get him just to spite them gals. They could kiss my black ass,” I says. And I got him.

Buster and me lived together and had Gabby. The baby come out black like me with nappy hair — like me. I still loved him, though. But then something happened. Buster got killed working on the docks as a stevedore. In DeRenne if you black you work the docks; if you white, then you get rich or drown in hate. And that man Buster brought home some money, let me tell you. We was living so good that I sent Gabby to the Catholic school and everything. That was so he could mix with a better class of children. But all that ended when a crate or a bag or something crushed my man. Burst his backbone wide open so much so that the undertaker say a piece of bone shot clear through my ginger man’s big heart. Busted that heart like a skin sack of wine. I cried, Lawd, I cried. And dreamed that if I had kept him home that day or laid up and pleasured til noon, if I had done something to keep Buster off that dock where somebody loosed his grip or wasn’t looking or was too drunk or tired to catch whatever fell on my man . . . I cried because he was gone, and I cried because I could’ve saved him. I cried because I was alone with a baby who would never really know his daddy, the man that was sprinkled in brown spice all over.

Things got bad and I moved in with my mama. No money, no nothing. Buster had some insurance, but the policy man come to my mama’s house and say that me and Buster was living in sin. We weren’t married in the eyes of the law. I told that cracker that the sin was that I was a woman alone with a baby and no way to support herself. That was the gattdamn sin — forgive me Jesus. At least some money shoulda come to our little boy! The cracker reared back on his heels and stuck his gnawed thumbs in his suspenders and said that unless I had some papers showing that Gabby was Buster’s baby, then the child could be any nigguh’s bastard. White folks always got to have some paper when it comes time to give something up, but when it’s time for taking they got no use for formality, I thought then. “Business is business,” he said and marched off the porch like he had conquered something.

Mama heard everything that the insurance man said, so she knew I wasn’t getting any money. And it didn’t take long for her to start acting funny-like. I knew she didn’t want me and Gabby around if I didn’t have nothing to give her. And she knew I knew.

So one morning I got our things together and just walked off. Mama didn’t even ask where I was going, she just stood in the screen door humming some church song. But all that was long ago and I don’t spite her none how she acted. Mama’s dead and I still don’t cry for her neither. Nothing leaves nothing. You can’t pretend that ain’t the world.

Anyway, Gabby and me made okay. I cooked for white folks, some nice, some nasty — especially the men that would try to get up my dress. And Gabby grow up big and fast, got a job and started looking out for himself. And he would bring his wages home to me every week, and say, “Here’s our money, mama.” Did not do no drinking, cussing or cutting-the-fool, my Gabby. As a man, he didn’t remind me none of his daddy — at least lookswise. But he was a worker like his daddy and I was proud.

Then the war come and they called Gabby. I seen him in his uniform too, marching down Bull Street, stepping high with the other boys. Over there was where the war was and he was stepping! I was so proud that day, so nobody could tell me nothing. Even the crackers who was up on the balconies of the fine Bull Street houses, the ones with the iron banisters tipped with gold — even those crackers who’d be cursing and shouting at the fine colored boys, the ones like Gabby in the green shirts that matched the color of oak leaves, even they couldn’t make me mad that day. Gabby always done right.

A colored lady was standing next to me in the street and I say to her that them crackers gonna be shamed when they see how brave the colored boys gonna be in the fighting over there. The lady’s boy was in the parade too and she said to me that she had hoped her boy had run off to Camden or somewheres as long as he could get away from the crazy crackers who wanted our black boys to die for them. I says to her that the boys be fighting for their country. She looked at me as though she didn’t know what I meant by “their country.” But I meant country the way it was something other than those devilish crackers on the balcony. That’s the way it was always taught to us. But that woman must’ve heard nothing about that and so she drifted away from me.

Getting killed? My Gabby looked too good to be laid out in some pine box. He looked too good in his green suit like oak leaves.

Gabby sent me letters from France. He sent me a postcard too, with a picture of him and a white gal. I remember that one good because I had to go down to the post office and get it. The man wouldn’t deliver it to my house. I even had to see the postmaster, on top of that. He, the postmaster, was one of them brown-teeth peckawoods. Chewed tobacco so long that when he talked his mouth looked like it was full of shit instead of gums and teeth.

The postmaster handed me the postcard. It was just a picture of a little white girl giving Gabby a basket of flowers. She was just a child. Then the postmaster looks at the picture and looks at me like I done something to him. He spit some of the stool from his mouth and says, “I’m from Mississippi.” I knew right then just what he meant.

I wasn’t gonna put up with no mess. I says to him, “Well, I guess you feeling pretty homesick.” I was being uppity. That made him mad, so he hocked up his britches and shook his finger in my face. “Mammy, you batter watch yo’ black ass!” I told him, “Sugar, if I’m yo’ mammy, then you better watch yo’ black ass.” That fool didn’t have no comeback for that. I took my postcard and my pride and just walked on out of there.

Gabby sent me more pictures and letters. But for four months I didn’t hear nothing from him. I started to get a little scared, but I was still sure that he was coming home, marching up Bull Street the same way he left.

Then I got a letter saying Gabby was alive and coming back. He was just hurt a little, so he had to spend some time in Charleston, in a hospital for soldiers. Well, he wouldn’t be marching home but he’d be close by. I was excited. This was something good.

I went to Charleston the first day Gabby was to be back from overseas. I took the Silver Meteor first-class-colored all the way. That was the fastest train. To see Gabby I had to go up to this nice white lady nurse. She sat behind a big counter like they have in the post office. She was right pretty in her white dress and funny bonnet, just like the picture of an angel. I thinks to myself: a nice white lady, she must come from up North. And she spoke to me so sweet — I was about to bust. I asked her about my boy Gabby. She leafed through a yellow-paged book as thick as a Bible and spotted Gabby’ s name. She sucked air between her teeth — they was so white and straight — and tells me Gabby had come in the day before. My heart sunk. I had traveled fast and hard to meet him getting off the boat and this white lady angel was telling me that I was too late. I said, “How come, ma’am? I come like the letter say.”

She scrunched up her face like I had bothered her and said, “Aunty, those plans were changed. The hospital ship was supposed to have made a stop at Norfolk to let some of the nigra soldiers off, but the whole Virginia bunch of them died before getting there. So, you see, the ship made the run in a little less time.”

To tell the truth, I wasn’t much listening to that nurse no more. All I wanted to do was see my boy, since he was already there. The nurse told me I could see Gabby any time I wanted because the doctors was going to let him loose the next day anyhow. She pointed me in the direction of some steps and said Gabby was that way.

I shot up those stairs like a cat-on-fire. But I didn’t know where I was going. The place was big with people, mostly white folks running in every direction. So I looked around until I found a colored face. Walking through some swinging doors, I got lucky. It was a boy in white clothes carrying a white porcelain bowl with a rag over the top. He was a short-fat joker with the kind of pale yellow skin you usually find on the nastiest Pullman porters. I walked up to him and asked where I could find Private Gabriel Ben Sidon.

The man rolled his eyes up in his head like he was looking for something in there, then he asked, “Is this Sidon guy your boss’ boy or your’n?” I say he probably knows my boy by the name Gabby. The man asked me the same question again.

“Gabby be my boy!” I sort of hollered and the man’s eyes focused. I was standing close enough to him that I could feel the warmth from whatever was in the bowl he was carrying. It was food, I thought. Gabby wasn’t doing so bad after all! They got colored waiters in this place, I was impressed.

I started to describe how my boy looked, but the man cut me off. He said there weren’t but four or five colored boys in the whole hospital and they were in the colored wing. I asked him if he worked there. He said, “Sometimes.” He said he was going in that direction, so I could walk along with him. I followed him back down the stairs to the first floor and out a side door to another building. This building wasn’t as nice as the others. The windows were small and high and they were smeared with what looked like grease. We came to a stairway and I started walking up. The colored man yelled for me to follow him. We went down instead of up, down into the cellar. This is where they keep my boy?

The stairs down stopped at a long hallway that had one naked hanging lightbulb way down at the other end. I let the man lead, it was dark. After a few steps, he said, “Wait here. I got something to do.” And he stepped into a doorless sideroom. Like the hall, it was dark, but a lot hotter. The waiter with porcelain bowl went over to the far wall of the room and flicked a switch. The wall opened up like jaws and in its mouth was a fire like I had never seen before. It turned the room orange! The man reached under the rag over his bowl and pulled out a white hand. I saw it! I saw it. He chucked the thing into the fire and flicked the switch again. The wall closed up and the room was pitch-dark again.

“Well, ma’am, that’s my job,” he says, now wiping the pus and blood from his hands with the rag. “Now let’s see if we can find Private Gabby.”

I followed him down the hall again. My legs felt numb. The closer we got to the lightbulb, the lower the ceiling got. The man was stooping over to keep from hitting his head on the pipes that hung down. There was a door under the light.

“This is it!” he said. I didn’t want to believe that this was the place where the proud boys in green oak-leaf uniforms were put. “This is the colored wing and if your boy ain’t croaked, then he’s gotta be in here.”

Behind the door was a little room, the ceiling was as low as the hallway — no windows. You could smell the sickness, that sweet smell that isn’t pleasing. It swells up in your throat and chokes you like tears. It’s a smell that says to you whatever you done and whatever you gonna do is useless.

There were four cots in the room and three men. Gabby wasn’t there! The nurse-lady’s yellow Bible was wrong. I had just known my boy was gonna come back. I start thinking Gabby was probably in a croaker sack, down in the water off Norfolk. No, I didn’t want to believe that. Gabby dead? I wanted to scream. Not thinking right, I spinned around to ask the burning man where the rest of the colored boys are kept at, but he was gone. The tail of his white coat was disappearing down the hall. I coulda chased him, but I didn’t, I didn’t move. I didn’t say nothing.

The three boys laid in their beds just looked at me. They didn’t say nothing. They didn’t move. Standing there in the only colored place in the whole sickhouse, standing there in the middle of a stinky little room — in a cellar, in Charleston — standing for such a long time and wondering, I was all drawn up. I was sucked up to one hellified spot to find out that I had lost SOMETHING. My boy Gabby. I was all drawn up and shoved in this corner with the eyes of them boys on the cots. They were red and glittering with cold and pain like the eyes of some sorry rats. And my boy wasn’t even among the rats.

I had to ask the boys, if just to hear myself talking, to make sure that I wasn’t as dead as I felt in that hole. “Where is Gabby?” I said it loud and it seemed as though glass was breaking. The boys in the bed began to mumble and shiver. The boy in the bed next to the empty one talked.

“Gabby? Gabby? My man is here! He on the toilet now, right ’round the side.”

“Mama?” My boy’s voice came from a near place.

“You here, boy? Where you at?” I shouted back. And then he came out from a side door. I didn’t look at him. I didn’t see nothing. I was blind — the tears, the kissing. My boy. My boy. Gabby? I didn’t feel his bones where once flesh wrapped him with mannish power. I didn’t hear him cough so deep from inside that it seemed that his innards were liquid. I didn’t notice the sagging air that followed him to his cot where he melted wearily from my arms.

Glad to have you back, son,” I said to him as we walked into our house. It wasn’t much of a house, just a tarpaper shotgun on the edge of Frogtown. At first he didn’t hear me, he rubbed the bare wood banister on the porch and then as though he was waking up from a dream he nodded and smiled my way. He was tired. The coughing seemed to get worse on the train ride back to DeRenne. A Pullman porter, a nice one, had some tabs of tar — tar always cleared up Gabby’s coughing when he was a baby. I’d just slip him a piece, he’d suck on it and the coughing was gone. The porter charged me half-a-dollar for the stuff and it still didn’t do no good. Gabby just coughed until he cried from the paining in his chest. When he talked on the train it was about the fighting over there — not looking at me when he talked. His eyes couldn’t face mine. And when he weren’t talking he’d just stare out the window, looking at nothing in particular, just staring.

“Mama, I seen . . .” he kept saying over and over again. “Mama, I seen too much.” I’d say that I knew, but I really didn’t. I knew nothing of the fire he spoke, must’ve been horrible fire and smoke, must’ve smell like Hell almighty, that flaming he said was over there.

“It took his — Booty Boy, my partner. The thing come out the dark and took his head off. Booty Boy’s head was in the hole by my foot. And his lips were moving like they was saying, ‘Run, Gabby. Run!’ His lips was still moving and I loved Booty Boy like a brother and I got scared. I got scared and kicked the thing out my hole, out my face, up in the bushes. Mama, I seen . . . ”

Then my boy’s eyes would water up and he’d look away from me, off in the comer of the room. Or if we were on the front porch, he’d look at the sky, but it was a look of emptiness, a look of shame.

“And Mama, they put smoke on us that burned your insides like somebody done poured hot grease down your mouth. I got a little bit of that smoke,” he say to me on the porch one night when my eyes had asked him for the um-teenth time of his sickness. I knew he wasn’t going to get better. I knew he hurt all the time. If he had a hole in him, I could patch it. If his leg was cut off, I could find a fine sapling and make him a crutch or he could just lean on me. But there was some thing inside of him, some white folks’ smokey demon devouring the organs and sucking away his young life. Lawd, if I could’ve reached in him and yanked that thing out. But it was a private something. If he could say, “Here, Mama. This is ours. Take it and do what you will,” like he’d do every Friday with his wages. But Gabby didn’t earn this thing! “Take this thing and get the fixings for a sweet potato pie I likes so much.” And I would’ve took it and run, run deep into the biggest pasture and buried it, buried it next to the Hell that it came from.

One day I went out the house to tell him to come eat. It wasn’t more than a month since I brought him back from Charleston. He wanted to go back to work, make some money, make me happy like before. Gabby was like that. But I say he ought to take it easy with his gagging and coughing. And he say, “No matter, Mama. I gets better day-by-day. You see it.” I’d lie to him and to my self. I’d agree.

It wasn’t a month since he’d been back when I walked around the side of the house and found him. He was on his hands and knees like he was praying. I found him there in the dust coughing and gasping for air. On his hands and knees — like a dog — he seemed to bark. The water in his chest growled and bubbled like happy feet on a church floor. Then he coughed hard once and strangled on that thing. I would’ve taken it and made him happy again and made things like they used to be.

Strangling, he looked at me with his eyes full of tears. He was so ashamed. I wanted to snatch him to his feet and say, “You a man, my son! You a man!” But the thing took his air away. He shuddered like he was cold and then it come out. A long black rope of blood spilled from his mouth into the sand. And already the green flies had gathered for the feast.

If you become a mother in this mean world, then you’ll need a stick one day.

Tags

William Pleasant

William Pleasant grew up in Georgia and now lives in New York City. (1993)