Repealing the Death Penalty

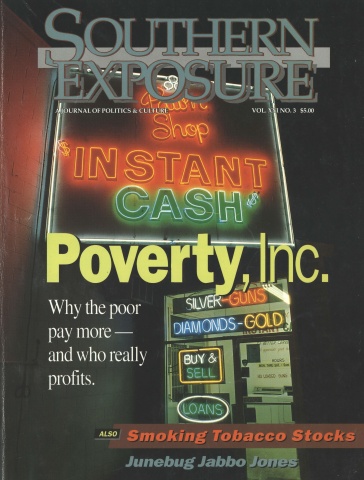

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Since the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed the death penalty in 1976, more than 210 people have been executed nationwide. The South accounts for most of the state-sanctioned killings — 44 percent in Texas and Florida alone — and another 1,392 Southerners are locked up on death row. As lawmakers call for more “get tough” measures to combat violent crime and an edgy public demands blood for blood, supporters on both sides of the capital punishment debate expect the death toll to climb.

Fortunately, in this chilling climate the winds of change are slowly gaining strength. Across the region, activists who oppose the death penalty are gradually making headway in the quest to abolish executions. In North Carolina, for example, state lawmakers recently voted to repeal the death penalty for mentally retarded defendants and for juveniles 17 and under. Activists have revived North Carolinians Against the Death Penalty, a statewide coalition that broadens support for reform. And last year, then-Governor Jim Martin granted clemency to Anson Maynard, a Native American wrongly convicted of murder — underscoring how fallible our criminal justice system can be.

Such accomplishments represent significant milestones that offer encouragement to human rights advocates everywhere. Yet pressing questions remain. What next? Where is the anti-death penalty movement headed? How do we make our message accessible and compelling to a fearful public?

The immediate answer to “what next” lies in lobbying. As the number of executions in the South continues to rise, we must step up our efforts in state legislatures across the region. At the top of the agenda are efforts to:

▼ narrow the range of defendants subject to the death penalty. Children already receive protection from execution in most states, but a dozen mentally retarded people have been put to death in recent years. We must convince policymakers to act immediately to prevent such tragedies from happening again.

In the South, Georgia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky have exempted the mentally retarded from capital punishment, but similar reforms were defeated this year in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. In North Carolina, both chambers of the General Assembly voted this year to end executions of the mentally retarded, but the Senate effectively undermined the measure by lowering the I.Q. criterion from 70 to 60 — well below the level of most mentally retarded people. North Carolina Senate and House conferees will meet next spring to work out a compromise on the bill. Anti-death penalty activists and advocates of the developmentally disabled should call or write state representatives, urging them to raise the I.Q. criterion to its original level.

▼ build coalitions that broaden our support and tap the leadership of new constituencies. In North Carolina, death penalty activists joined forces with child advocates in the fight to exempt juveniles from capital punishment, and with advocates for the developmentally disabled in the push to exempt the mentally retarded. Although the nature and politics of each initiative were distinct, both produced important human rights victories.

▼ develop relationships with legislators to gauge their interests and perspectives on criminal justice issues. Virginians Against State Killing conducted a “Listening Project” with state lawmakers last year, asking them to share their personal feelings about capital punishment and explore its alternatives. As a result, legislators felt like they were listened to instead of yelled at — while activists gained important insights and laid the foundation for further discussions.

Beyond the immediate demands of lobbying, the “what next” of the anti-death penalty movement must involve a long-term effort to reframe the debate and reclaim the voice of reason and justice. The movement to abolish executions is too diverse and multifaceted for any single strategy to work. Yet one thing is clear: Those of us who oppose the death penalty must become more effective in connecting with ordinary citizens who support it.

All too often, conservative supporters of capital punishment pigeonhole opponents as liberals who are “soft on crime.” This predictable argument suggests that we care more about murderers than victims, marginalizes the movement, and creates an “image roadblock” that hinders our real message from being heard.

To overcome this misperception and reach out to new constituencies, activists need to:

▼ emphasize the common ground we share with those who support the death penalty. Most people who support executions want safe communities and a criminal justice system that is fair and responsive; antideath penalty activists desire the same. These common interests offer fertile ground for creating a more humane criminal justice system devoid of capital punishment.

▼ present our case unapologetically. We must not be afraid to articulate the values, principles, and facts that lead us to oppose capital punishment. Different constituencies offer different strengths: Church groups often provide the clearest moral vision for repealing the death penalty, while grassroots organizers and legal advocates can marshal strong research underscoring the importance of alternatives.

▼ emphasize cost-effective ways to reduce crime and offer alternatives to death. Every study demonstrates that even with fewer appeals, the death penalty costs significantly more than life imprisonment. And violence prevention is even cheaper than punishment. Teaching children conflict mediation skills, treating substance abuse, providing meaningful employment and job training — these strategies address the root causes of crime, reduce the need for punishment, and make communities safer.

▼ recruit the family and friends of murder victims as visible allies. Many don’t want revenge, and say state-sponsored killing cannot heal their wounds. Their stories are compelling — and their voices command genuine respect from the media and policymakers. They can also provide a key link to victim’s rights groups, drawing attention to the violence of the death penalty.

▼ develop relationships with the media. Newspapers and television fuel the public fear of crime and oversimplify our case against the death penalty. Activists and our allies need to respond to specific misinformation perpetuated by the media. We must also provide resource packets that present the facts clearly, as well as credible spokespeople who can define our agenda in a concise and persuasive manner.

In the world of the 30-second sound bite and USA Today-length newspaper articles, perception is three-fourths of the battle. To reclaim the public image of our movement and reshape the substance of the death penalty debate, we must devote more attention and resources to marketing our message. That means developing “catch phrases” that both perk the ears of a restless citizenry and affirm our commitment to an effective criminal justice system. One organization in North Carolina, for example, has broadened its appeal and attracted new members by emphasizing the phrase “working for safe communities.”

Whatever the specific strategy, reaching out to ordinary citizens is critical if we hope to repeal the death penalty in its entirety. It won’t be easy. The number of state executions continues to rise each year, and federal and state officials want to speed up the killings by putting more limits on legal appeals. We must step up our efforts to take our message to the public in an effective and unwavering manner. Doing so can only hasten the winds of change, drawing more and more people into the movement to abolish the death penalty.

Tags

Leigh Morgan

Leigh Morgan is a staff member at the Carolina Justice Policy Center in Durham, North Carolina. (1993)