This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Across the South, big corporations are making billions of dollars in profits by targeting the region’s most economically vulnerable citizens. Poor and working-class people. African-Americans, Hispanics, and other minorities. Middle-class consumers who suddenly find themselves jobless or overwhelmed by bills.

Each year, millions of Southerners are swindled, ripped off, or gouged by exorbitant prices for loans and basic financial services. They are targeted because they lack the income, credit history, or skin color to qualify for the fair-market rates and above-board treatment offered to more affluent — and mostly white — consumers.

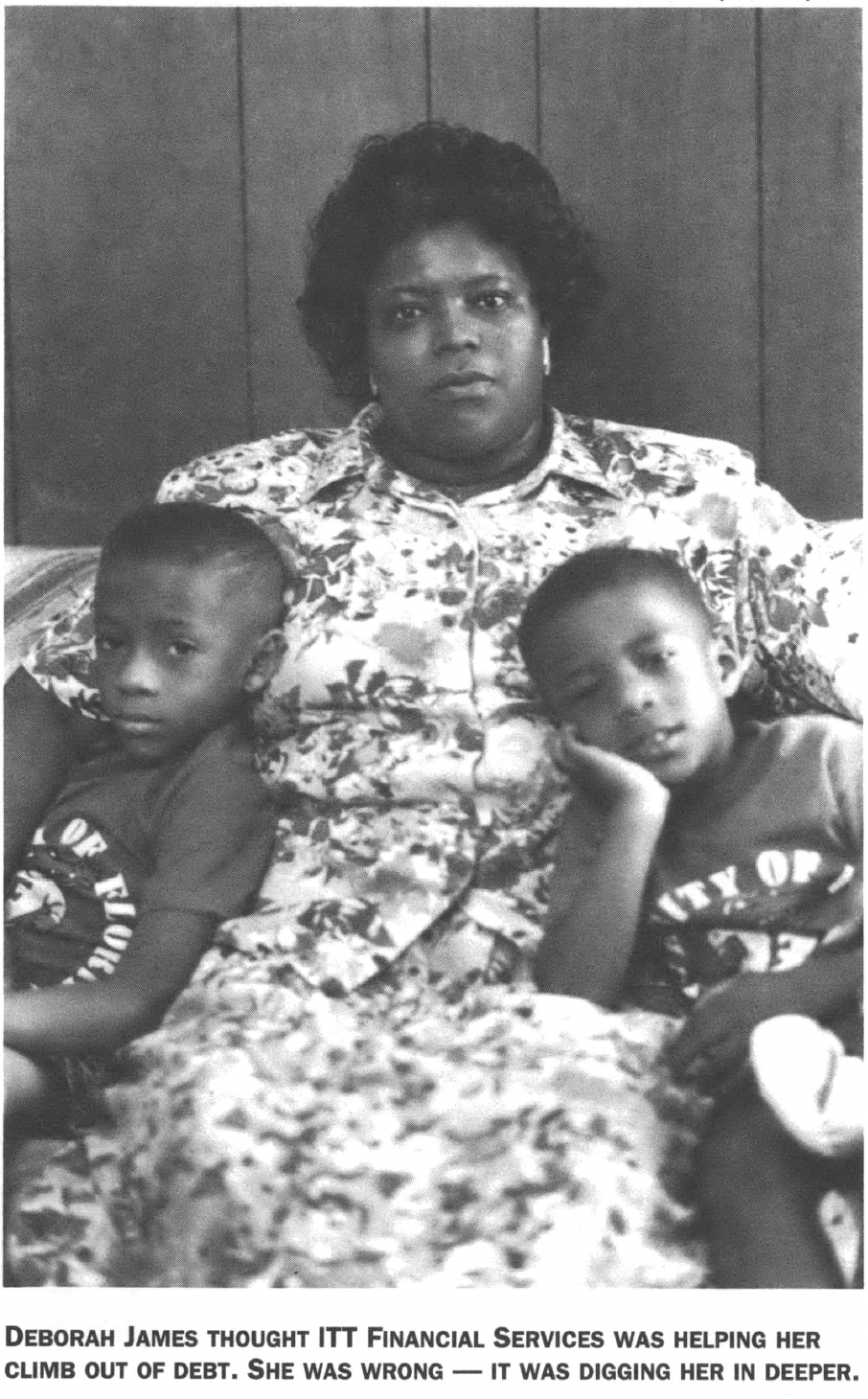

They are people like Deborah James.

Deborah James shushed her baby as he cried and wriggled in her arms. She was worried. She was in debt and could see no way out.

“Stop Adrian,” she told her son. “Quit, quit, get up.”

Across the table, a loan officer with ITT Financial Services in Jacksonville, Florida was oozing concern.

“He’s just tired, that is what his problem is,” the loan officer said. “I’ll get you out of here buddy, just give me a little time. He can smile, give me a smile.”

He pushed some papers in front of James.

“Look at that. OK, then this one right here. And this one right there. And this one right there.”

She signed a few more, and it was over.

“If you’ve got any problems at all don’t hesitate to call me,” he said. “I’ll give you my card, so don’t get behind that eight-ball anymore. You can always call me and I am sure that we got a solution.”

James thought ITT was helping her climb out of debts to a waterbed store and health spa. She was wrong. It was digging her in deeper.

Once the finance company took over her debts, it rewrote her loan contract five times over two years — lending her $2,669 to pay off bills.

James paid back all but $45 of that in monthly installments, but her debt now totals more than $4,000. Why? Because ITT charged her interest rates between 21 percent and 30 percent, tacked on fees each time it rewrote the loan, and billed her more than $1,600 for credit insurance, an item consumer advocates say is virtually worthless to borrowers.

When James couldn’t keep up with her payments, collectors working for the company called her home. Sometimes late at night. They called her at work. They called her mom.

“It really and truly hurt me that they would take advantage like that — in such a disguise that everything they were doing was for my benefit,” James says.

Other ITT customers report the same mistreatment. The company charged Art Wrightson, a restaurant manager in Tampa, more than $600 for credit insurance on a loan of less than $2,600. “They’re flat-out slick,” he says. “They’re taking advantage of a lot of people.”

Gertrude Stuckey, a cafeteria worker in Jacksonville, ended up more than $4,300 in debt after borrowing money from ITT to pay a $500 dental bill. When she couldn’t pay, she says, the company harassed her unceasingly.

“They laughed,” she recalls. “They thought it was funny when I said: ‘You’re violating my rights.’”

The New Loan Sharks

Low-life leg-breakers and con men operating from grimy storefronts aren’t the only ones preying on the vulnerable. These days, most of the profits made from gouging disadvantaged consumers flow into the balance sheets of big banks and major corporations like ITT. They are well-known, respected, insulated by the advice of powerful law firms, oftentimes traded on Wall Street.

Some break the law. But most simply take advantage of harsh economic realities and lax government regulations that leave many consumers with few choices and little clout in the marketplace.

“Everybody is taking their pound of flesh every time a poor person does a transaction,” says Gary Groesch, a housing activist who now heads the Alliance for Affordable Energy in New Orleans. “If poor people got an even deal, that would be a miracle.”

The poverty industry begins at the bank door, where poor and minority consumers are shut out of mainstream sources of credit. Government studies and media investigations in recent years have repeatedly demonstrated that major banks systematically “redline” entire neighborhoods, refusing to lend money to the people who need it most. They also charge stiff fees for small accounts and bounced checks, making it tough for consumers with modest incomes to get access to basic financial services.

As a result, more and more Americans find themselves living in a financial ghetto, cut off from affordable credit. Yet the banks that put them there still find a way to make money from their discrimination. Major financial institutions advance money to front companies — trade schools and tin men, used-car dealers and pawn brokers, finance companies and second-mortgage lenders. These businesses then loan the money — often at sky-high interest rates — to people the banks won’t do business with themselves.

“These scams have existed for a long time,” says Marty Leary, research director of the Union Neighborhood Assistance Corp. (UNAC), which is investigating lending abuses across the nation. “What makes them different is the massive scale, the fact that they’re very efficient profit generators for a very small number of people. It’s a centralization of power and economic resources brought into communities on very predatory terms.”

The result is a debtors economy where everybody profits — except the poor. They are trapped into a separate but far-from-equal banking system where they pay more for everything.

There is no way to calculate exactly how much consumers pay for unfair credit; consumer debt now totals $4 trillion, and many transactions go unreported. It is clear, however, that millions of Americans lose billions of dollars each year. Marty Leary of UNAC estimates that mortgage lenders and finance companies alone make at least $70 billion a year in predatory loans.

The list of businesses that target the poor for profit is long. Among the biggest money gougers:

▼ Second-mortgage companies work hand-in-hand with mainstream banks to target poor and African-American homeowners. Contractors and mortgage brokers prowl minority neighborhoods offering loans with interest as high as 30 percent to pay off bills or make home repairs. Big banks finance the operations — and then “buy” the loans to collect the interest themselves. Fleet Finance, the Atlanta-based subsidiary of the largest bank in New England, has been accused of fleecing more than 20,000 borrowers in Georgia.

▼ Fringe banks — pawn shops and check-cashing outlets — make big profits by serving customers who have been locked out of mainstream banks. Check cashers typically charge two percent to 10 percent of a check’s value to cash it. In many states, pawn shops charge interest as high as 240 percent.

Business is booming. The number of pawn shops has doubled in the past decade to an estimated 10,000. Since 1987, the number of check cashers has jumped from about 2,000 to an estimated 5,000.

▼ Used-car dealers take in billions of dollars a year, often working in tandem with banks and finance companies to set up low-income and credit-damaged customers for price gouging and loan schemes.

“For people who have bad credit, you’re gonna have to take what they give you,” says Rick Matysiak, special investigations coordinator for the Georgia Department of Insurance. “If you’re gonna pawn off a car that has been cut in half and put back together, you put it to the people who have the least ability to fight back.”

▼ Finance companies like ITT Financial Services make huge profits by serving as high-interest lenders of last resort for borrowers with limited income or shaky credit. Consumer debts to finance companies now total more than $115 billion.

All but three Southern states allow finance companies to charge maximum interest rates of at least 36 percent a year — including 109 percent in Tennessee and 123 percent in Georgia.

▼ Rent-to-own stores have become a $3.7 billion-a-year business by selling appliances and other household goods by the week or month to low-income customers — charging them as much as five times what they’d pay for the same items at traditional retailers. The industry has tripled in size in the past decade amid a frenzy of corporate buyouts and increasing chain ownership. A third of its 7,500 outlets are in the South.

▼ Trade schools use easy access to federal loan money and the promise of better jobs to take advantage of low-income students. The schools — and the banks that finance them — have left hundreds of thousands of students stuck with the bill for billions of dollars in fraud-tainted profits (see story, “The Perfect Job for You”).

▼ Debt collectors do the dirty work when consumers can’t pay, using threats and manipulation to make sure lenders get their money. One consumer advocate told Congress that collection agencies and in-house bill collectors working for lenders have become “nothing more than terrorists” holding people hostage to their debts.

John Long, an Augusta attorney active in the Republican Party in Georgia, once represented big companies. Now he defends consumers. “I got tired of being the guy who had to go out and screw somebody,” he recalls. “You’d say: This is illegal, you can’t do that. They’d say: We’re gonna do it anyway.”

Long says the small-time shysters that have long ripped off the unwary are nothing compared to the big corporations that now prey on the poor. “These guys that do it today — they’ve got it down to a science.”

“They Keep You Poor”

One reason getting cheated on a loan hurts so much is that it usually leads to a cycle of more and more debt. That’s what happened to Audery Duncan after she signed up for classes at the Crown Business Institute, a trade school in Atlanta. She says school officials promised to teach her to read, but never did. She ended up stuck with a $2,500 student-loan debt to First American Savings.

Her credit was ruined, and Duncan had to go to a rent-to-own store when she needed bunk beds for her daughters. She pawned her engagement ring to pay for food and clothing. And because she cannot get a checking account, she now pays a $5 fee to cash her welfare check at a downtown Atlanta bank.

Bufford Magee, a New Orleans cabbie, pays $308 a month to three finance companies, including one that financed his bedroom furniture. “They’ve got two guys riding up and down the streets. They stopped me one day. I said, ‘Man, I don’t need no bedroom.’” But he finally relented. “Come to find out the bedroom ain’t worth nothing. It was sheet material. They made it themselves.”

Magee tried to get bank loans, but they refused him. “When the banks won’t lend you money, what you gonna do? I try to live decent. I work seven days a week.”

He held out an olive-green payment book from one of the finance companies. “You end up paying 40, 50 cents on the dollar,” he said. “They keep you poor that way. You can’t never get on your feet.”

The Seven Dwarves

For decades, one of the most profitable ways to keep poor people poor has been to go after the money they have invested in their home. Second-mortgage companies persuade homeowners who have been turned away by banks — especially African-Americans — to take out high-interest loans for bill consolidation or home repairs (see sidebar, “They Won’t Give You a Chance”).

Over the past decade, however, a new innovation has fueled the rapid growth of this scam: A growing number of banks and S&Ls now buy these loans on the “secondary market.” By purchasing the right to collect on these debts, bankers can earn money on the loans while claiming that they bear no fault if the deals turn out to be tainted by fraud. Companies hit with allegations of mortgage abuse include ITT, Security Pacific (now owned by Bank America), and Chrysler First (recently purchased from Chrysler Corp. by NationsBank).

The Debt Massacre

Three years ago, James Pough walked into the General Motors Acceptance Corp. office in Jacksonville, Florida and opened fire. He killed nine people before he took his own life.

At first, the worst mass murder in Florida history looked like just another example of a gun nut gone mad. But now court documents charge that predatory credit and collection practices by the loan company helped push Pough to the breaking point.

Pough bought a 1988 Grand Am from a local Pontiac dealer. According to WJKS-TV in Jacksonville, the dealer valued the car at $9,125, but warranties and other tacked-on costs increased the price to $15,300. On top of that, GMAC financed the loan at 19.8 percent interest. Payments were $392 a month. Pough, a laborer earning about $400 a week, paid $3,500 before he couldn’t pay anymore.

GMAC took back the car and auctioned it off — and then informed Pough he still owed $6,394. Yvonne Mitchell of the city Consumer Affairs Division says Pough complained to her that GMAC collectors were arrogant and nasty. “I remember him telling me he offered to make a payment, and they refused it,” Mitchell told the Florida Times-Union. Instead, she says, GMAC wanted the whole amount — right away.

After Pough’s rampage, husbands of two of the victims sued GMAC, saying officials had endangered workers by making loans “to people that they knew couldn’t pay.” As far back as the early 1980s, a top company executive had similar concerns. He wrote branch offices to ask, “Are we buying marginal or poor risk paper knowing that extremely difficult collection measures are going to be necessary? Are undue pressures being exerted on field employees and credit employees to conclude assignments, at any cost?”

The lawsuit has yet to go to trial. GMAC denies it did anything to put employees at risk. It has asked a judge that documents in the case be sealed as “trade secrets.”

SIDEBAR

The Great Mobile Home Rip-Off

For many Southerners with modest incomes, mobile homes have long afforded the best hope of having a place of their own. “Manufactured homes” are the fastest growing form of housing in the nation — with sales jumping 60 percent during the 1980s and 23 percent last year alone. The $6 billion-a-year industry also holds another distinction: It’s been riddled with more fraud in recent years than just about any other business in America.

In the mid-1980s, manufacturers representing more than half the mobile-home market were indicted for padding factory invoices in order to inflate profits they earned through loan programs run by federal housing and veterans agencies. Investigators said the scheme gouged more than $100 million from low- and moderate-income borrowers. Veterans officials estimated manufacturers padded invoices on at least 80 percent of the 295,000 mobile homes shipped in 1984.

Such corruption was widespread. “I’m glad everybody else has been told to stop,” said former First Brother Billy Carter, a top executive with Scott Housing Systems in Waycross, Georgia. “It would have been hard to stop if everybody else hadn’t stopped.” Scott paid a $50,000 fine.

Many who were cheated were unable to repay their federally guaranteed loans. In 1990, federal officials estimated that veteran and housing programs had lost more than $650 million on bad mobile-home loans. Federal investigators urged — without success — that the loan programs be scrapped because of widespread mismanagement and fraud.

Michael Calhoun, a Durham, North Carolina attorney who has represented more than 5,000 mobile home owners, says new buyers often pay interest rates of 14 percent, and many earlier buyers are still locked into through-the-ceiling rates from the 1980s. Mobile homes drop so quickly in value, Calhoun adds, that it’s almost impossible to refinance and get lower interest rates.

“I’ve got people paying over 20 percent on a 15-year mobile-home loan,” Calhoun says, “and they’re still paying it today.”

In Georgia, Fleet Finance has been sued for buying thousands of mortgages from a group of loan brokers nicknamed the “Seven Dwarves.” Almost all the loans had high fees and interest rates — especially for blacks. A state judge determined that black homeowners held 60 percent of the Fleet loans with the highest interest rates. Blacks also paid upfront fees of 11 percent, while whites paid eight percent. Homeowners nationwide averaged less than two percent.

Fleet officials deny they ever had control over the brokers. But court records show that four of the companies sold more than 96 percent of their loans to Fleet, and Fleet admits it “pre-approved” many of the loans before the brokers closed the deals.

Last summer, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled that Fleet has not violated the Georgia loan-sharking limit of 60 percent annual interest. But the justices said the bank’s practices “are widely viewed as exorbitant, unethical, and perhaps even immoral” and urged state lawmakers to put stricter limits on second-mortgage rates.

Fleet has meanwhile profited handsomely from the absence of real regulation. In 1990, the finance company made $60 million on its national portfolio of 71,000 high-interest loans, at a time when many of its parent company’s mainstream banking operations were losing money. Those profits — along with money from the student-loan business — gave Fleet the clout it needed to take over the Bank of New England in 1991. Thanks to that deal, company assets now total $45 billion.

From Whispers to Wall Street

Banks not only shut off credit to poor consumers, they also make it expensive to maintain a checking account. According to a survey of 300 large banks by the Consumer Federation of America and the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, the average annual cost of a regular checking account hit $184 this year — up 18.5 percent since 1990, nearly double the rate of inflation.

Such price hikes have left many consumers unable to afford a bank account. According to the Federal Reserve, the portion of American families without an account has increased from 9 percent to 14 percent in the past 15 years.

That’s where “fringe bankers” come in. Pawn brokers and check cashers offer themselves as one-stop financial centers for the bankless. They sell money orders and lottery tickets, make wire transfers, take payments for utility bills, distribute food stamps under government contract, and make high-priced “fast tax loans” to customers who can’t wait for their IRS refunds.

The “non-bank” market is being tapped by entrepreneurs like Jack Daugherty. Daugherty started small: Ten years ago he owned a single pawn shop in Irving, Texas. If he said “pawn shop” at a country club, people would turn away and whisper. If he had gone to an investment banker for a loan, they’d have shown him the door. Corporate America believed it was somehow above pawn shops and check-cashing outlets.

But thanks in large part to Daugherty, all that has changed. Back in 1983, after years of dabbling in night clubs and dry oil wells, Daugherty had an idea. The pawn business could boom, he thought, if it could overcome its shady image. His plan was simple: Give customers self-esteem. Make sure things look nice and the employees are friendly and fair, so people won’t have to feel like they have to slink into a pawn shop. Daugherty poured money into advertising, public relations, and charity drives, and soon found his Cash America chain of pawn shops on Inc. magazine’s list of the nation’s fastest growing companies.

Cash America is now traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Its symbol: “PWN.” It’s the largest of four publicly traded pawn chains based in Texas. All but a handful of its 245 pawn shops are located in the South. Last year, Cash America reported nearly $13 million in profits on $186 million in revenues.

With profits high, the rest of Corporate America is now rushing to cash in on fringe banking. A five-bank syndicate led by NationsBank Texas recently extended a $125 million line of credit to help Cash America expand. Western Union and American Express are diving into the check-cashing business, which collected about $790 million in fees in 1990.

But despite their image-polishing and new corporate look, there is one thing about the business that Cash America and other fringe-bank conglomerates have not tried to change: the prices. The average loan rate at Cash American hovers over 200 percent. Indeed, the chain makes no attempt to undercut the competition, charging the highest finance fees allowed wherever its stores are located.

“The reason for that,” Daugherty explains, “is we don’t want to alienate the industry.” If his prices were unfair, he adds, his customers would go elsewhere.

But many don’t have much of a choice. When Pacquin Davis, a public-housing resident in Atlanta, decided she wanted to break away from pawn shops and check cashers, she had to try three different banks before she found one that was willing to give her a checking account. The first two she visited, First American and Georgia Federal, turned her away because a furniture store had left a bad mark on her credit history. Georgia Federal refused to even allow her to open a savings account, she says.

Her Legal Aid attorney, Dennis Goldstein, says at least a dozen of his clients have been turned down for savings accounts at Atlanta banks because they have bad credit. That makes no sense, he says, because there’s no chance of bounced checks with savings.

Snubbing credit-damaged customers is one more way banks drive the poor away. “They just put that fear in your heart,” Davis says. “It kinda scares you to walk in that door.”

“Dead in the Water”

Customers like Davis who get turned down for bank accounts wind up paying more for access to their own money. John Caskey, a Swarthmore College economist who monitors fringe banks, estimates that a bank-less family earning $16,500 spends nearly $300 a year on check cashing and money orders.

Some check cashers take even bigger cuts. Last year, when the federal government sent checks to thousands of poor families whose children had been wrongly denied disability benefits, a big chunk of the settlement went directly into the hands of check cashers.

Delores Hagler, director of Social Security in New Orleans, says one parent reported that a check casher charged her 50 percent to cash a $16,000 government check — an $8,000 fee — because she didn’t have an ID. Other parents reported paying from three to 10 percent — often hundreds of dollars — to cash their settlement checks.

Such abuses are widespread. In Florida and Texas, dozens of check cashers have been accused of loansharking. In Virginia, the attorney general has sued five check-cashing companies that lend customers money in exchange for post-dated checks. In a typical transaction, a check casher loans a customer $200 in exchange for a $260 check that can be cashed on the customer’s next payday. The interest bite on these brief loans can equal annual rates of 2,000 percent.

Pawn brokers across the South, meanwhile, have been bilking the poor by pawning car titles. Customers sign over their title, pocket a loan, and drive away. If they can’t repay the money, the pawn broker gets the car. Interest rates can reach 1,000 percent.

One 66-year-old customer in Atlanta pawned his 1979 Mercury Cougar for $300. He agreed to pay back $545 over 12 weeks. When he fell behind toward the end, the pawn broker tacked on late charges and threatened to put him in jail. So he went to Legal Aid for help. His attorney found the loan contract listed the annual interest rate at 24 percent, even though the real rate was 550 percent.

“These people exist on people like myself who are stuck and broke,” says the man, who asked not to be identified. “If I haven’t got a car, it means I’m dead in the water. So they knew that and it means they can charge most anything they want.”

Repo Men

As the number of people who are “stuck and broke” has risen over the past decade, so have efforts to make money off them. Jack Daugherty, the pawn shop king, estimates the “non-bank” market includes 60 million Americans. So far, he says, pawn brokers and check cashers have tapped only 10 million to 15 million of those.

That leaves lots of room for expansion for the pawn industry — and for other businesses that serve the bankless. So it was no surprise when Daugherty and his chief financial officer at Cash America decided to open a chain of used-car lots for people who couldn’t get bank loans.

Urcarco opened in a big way. In 1989, it raised $43 million from investors across the U.S. and Europe. It became the nation’s first publicly traded chain of used-car lots.

Loan rates were high — 18 percent to 27 percent — but the company promised low down payments and better-quality cars. Its TV ads parodied its competitors by featuring a cowboy-fied salesman named “Bubba.” When he slapped the hood of a car, its fender fell off. Urcarco sales soon hit $38 million a year.

Then the bottom dropped out. So many loans were going into default, the company’s repossession rate hit 50 percent. Urcarco lost $24 million in three months. Company officials blamed overexpansion and the recession.

But were there other reasons why so many people were having trouble paying? In Houston, a class-action lawsuit accused the company of slipping hidden finance charges into its contracts and selling credit insurance at illegal rates to customers with shaky credit. One salesman told Forbes magazine that a customer needed just one thing to pass a credit check at Urcarco: “a down payment.”

“I did a lot of deals that I was told, ‘I don’t care what you do, but make it look like that guy can afford the car,’” a former Urcarco collector told the Dallas Morning News. “They try to act totally professional, but if you sit behind the doors at the lot, you find it’s not.”

A company spokesman denied any wrongdoing. In the end, however, Urcarco settled the class-action suit for $100,000. Late last year, the company sold off its inventory, changed its name to AmeriCredit, and shifted to the consumer-loan business.

Michael O’Connor, a Houston consumer attorney who won the settlement from Urcarco, says he’s seen lenders all over Texas tacking on extra charges — especially for customers who have been denied bank credit and have to rely on “second-chance” financing. “That’s when they turn the screws up,” says O’Connor.

In Tampa, Florida, one of the nation’s largest car dealers ran newspaper ads urging people with bad credit to call and ask for “Betty Moses,” a made-up name. Royal Buick and a loan officer at Florida National Bank then falsified paperwork to secure loans from the bank. Many buyers defaulted within weeks, losing their cars and their down payments. The banker and more than 20 Royal Buick employees were convicted of fraud.

Insurance Rip-Offs

Perhaps the most lucrative way that car dealers and lenders cheat customers is by selling credit insurance. Studies by the Consumer Federation of America and the National Insurance Consumers Organization show that borrowers are overcharged between $500 million and $1 billion a year on credit insurance.

Credit insurance is supposed to pay off a loan if the borrower becomes sick, dies, or loses the items put up for collateral. But consumer advocates say it’s overpriced and usually worthless, since borrowers rarely collect on their claims.

The law says borrowers cannot be forced to buy credit insurance. But the commissions that lenders earn from selling it are so generous, it’s hard to resist sneaking it into a loan.

ClayDesta National — a Texas bank controlled by Clayton Williams, the unsuccessful Republican candidate for governor in 1990 — has admitted it broke the law by forcing low-income, black, and Hispanic car buyers to buy credit insurance. The bank came up with $1.3 million to repay the victims.

A prosecutor said the scheme targeted people who had been denied auto loans, because it was easier to get them to “take it or leave it.” ClayDesta had been losing money since the mid-1980s and was ranked as one of the worst banks in the nation. But the illegal insurance sales brought in $500,000 a year and helped put the bank in the black.

A former loan broker said in a sworn statement that he had warned ClayDesta’s consumer lending chief it was illegal to force borrowers to buy insurance.

The banker’s only response, he said, was a smile.

Bankers aren’t the only ones smiling about credit insurance. Finance companies make much of their money from such deals, often by refinancing loans for the same borrowers over and over so they can collect new fees and more commissions. A national survey by First National Bank of Chicago found that two-thirds of finance company loans are made to existing customers, either through refinancings or add-ons to earlier loans.

What do consumers get in return? Not much. While other types of insurance typically pay 70 cents in claims for every dollar collected in premiums, credit insurers pay an average of only 42 cents. In 1991, the credit insurance subsidiary of ITT Financial Services paid only 29 cents on the dollar. That same year, one Georgia company, First Franklin Financial, sold $10 million worth of credit insurance — and paid out just 8.5 cents on the dollar.

All this adds up to incredible profits for lenders. In 1991, the small-loan subsidiary of Fleet Finance in Georgia pulled in $6.7 million and posted a profit margin of 75 percent, thanks mostly to credit insurance. ITT’s Georgia subsidiary did even better — taking in $9.7 million with a profit margin of 82 percent.

Last year the Georgia insurance commission fined Fleet $325,000 for overcharging borrowers for credit insurance. Court documents and statements by borrowers across the nation also show that ITT has aggressively packed credit insurance onto consumer loans — despite repeated warnings from state regulators that it was breaking the law.

Insurance abuses and other questionable practices push many borrowers into debt they cannot escape. By 1990, ITT had 100,000 customers in bankruptcy — about a tenth of the annual number of personal bankruptcies in the entire nation. The company also found itself facing a tidal wave of lawsuits in Florida, Alabama, and other states. It settled a class-action suit in Minnesota for nearly $49 million and an attorney general’s probe in California for $30 million.

Deborah James is one of hundreds of borrowers in the Florida case. She paid as much as $895 for insurance on a single loan. On her first few loans, James says, ITT added in credit insurance without asking whether she needed it. She didn’t. She already had all the insurance she needed through her job at Sears.

As ITT came under fire across the nation over its insurance sales, it began tape-recording its loan closings. Transcripts of James’ last two closings show that ITT did tell her insurance was optional on those loans. By then, James says, it seemed to be a regular part of the loan. She thought it was for her own good.

But when she tried to make a claim for jewelry and a TV that had been stolen from her home, the insurance company said no. The same thing happened when she made claims for medical complications after two pregnancies.

Kristie Greve, a spokeswoman for ITT, denies charges that the company has systematically cheated borrowers. “To have a few people stand up and say things like that. . . I think that’s a real slap in the face.”

Swimming in $600 million in red ink, ITT announced earlier this year that it was selling its portfolio of consumer loans as part of a “strategic refocus.” It plans to concentrate on second-mortgages — an area where it is also facing lawsuits in several states.

Renting the Dream

Global conglomerates, intent on creating new markets beyond paper loans, have taken to peddling dinette sets and color TVs to the poor. Thorn EMI, a recording and electronics company based in the United Kingdom, pocketed $443 million in profits last year thanks to assets like music superstars Garth Brooks and Tina Turner. In 1987, it jumped into a whole new venture, buying the Rent-A-Center chain for $594 million. Since then, Thorn has expanded its empire to 1,200 stores nationwide and now controls one-fourth of the nation’s rent-to-own market.

Why is the business booming? A trip to a Rent-A-Center in Roanoke, Virginia gives a hint: There you can buy metal bunk beds for $16.99 a week for 78 weeks — a total of $1,325. Across town at Sears, a comparable bed set can be had on sale for $405.

That, in essence, is the story of rent-to-own: selling on time at markups that are astounding. Three million customers a year pay the price. Nearly 60 percent of Rent-A-Center customers earn less than $20,000 a year. Just four percent earn $45,000 or more.

The rent-to-own business got its start in the 1960s as a way to skirt new laws designed to limit interest rates that inner-city merchants were charging customers who bought on credit. By redefining such transactions as rentals with “the option to buy,” rent-to-own dealers are free to charge interest rates of 100, 200, even 300 percent a year.

Rent-to-own dealers say their prices are higher because their repair costs are high, and because customers can return items at any time with no penalty. Bill Keese, a former Texas state legislator who leads the industry’s trade association, says rent-to-own helps people who have been shunned by banks and department stores. “Our customers have as much right to the American Dream as anyone else,” Keese says.

But behind the red-white-and-blue sales pitch is an industry that cannot break away from the crude habits of the old-time ghetto merchants it has replaced. Legal Aid attorneys say many rent-to-own dealers still sell used goods as new, break into homes to repossess merchandise, charge unfair insurance and late fees, and threaten late-paying customers with criminal charges. A West Virginia rent-to-own company paid cash settlements last year to four customers jailed on bogus theft charges sworn out by the dealer.

Several Southern states have laws that make “failure to return rental merchandise” a crime. Rent-to-own stores frequently use these statutes — aimed at people who steal rented cars or video tapes — as a powerful collection tool.

Donna Smalley, an attorney and law professor in Alabama who represents the rent-to-own industry, says many people who work in the business simply don’t understand that it’s not a crime to owe money. “You would be amazed at how many managers I have who say: ‘I can’t wait to pick that sucker up and put him in jail.’”

Collectors and Pallbearers

That sort of attitude is common among businesses that profit from the poor. Whether renting furniture to low-income consumers or getting debt-ridden homeowners to pay a second mortgage, many lenders use take-no-prisoners collection tactics to squeeze payments out of financially strapped customers.

Deborah James says ITT telephoned her at work so often she was afraid she was going to lose her job. An ITT office file on James dated June 16, 1988 contains a brief notation: “Pull File — Call all relatives. Ph POE [Phone place of employment] & get dept she work in — Call at home late at night.”

Although she had no money in the bank, James says, company agents asked her to write post-dated checks that they could cash as soon as she got her hands on any money. “I told them I did not do that,” James says. “But sometimes I’d do it just to get them off my back. I said: OK, I’ll do that and they’ll leave me alone — ’til the next time.”

Consumer attorneys and government regulators in several states say ITT has routinely harassed borrowers who have fallen behind. Last year the company paid $1.3 million to settle charges of collection abuses in Wisconsin.

Many creditors hire bill collectors to put the squeeze on debtors, and consumer advocates say collectors routinely use psychological torture to terrorize people.

Payco American Corp. — one of the biggest debt collectors in the nation — goes after $3 billion in debts each year. In August, federal officials accused the publicly traded company of threatening debtors with jail, misrepresenting collectors as attorneys, using obscene language, and other illegal tactics.

Carleton Fish of the American Collectors Association says reports of serious wrongdoing are “aberrations.” But government regulators report a growing number of protests about collection hassles. Complaints to the Federal Trade Commission about collection agencies have doubled since 1990 — to 2,000 a year. The FTC gets another 1,000 complaints a year about lenders who do their own collecting.

Many more abuses go unreported because victims are afraid to complain. A study by the Wisconsin attorney general estimates that only one in 100 people harassed by bill collectors ever complain to authorities.

The FTC has gone after individual collectors, but state and federal agencies have yet to tackle the industry in a systematic way. Lone consumers often feel they have nowhere to turn. arver Jones was living the American Dream: a home in an exclusive neighborhood in Houston, two BMWs, a generous line of credit. Then he hurt his back in a car wreck and lost his job.

His creditors sicced a New York-based collection agency on him. “They yelled and screamed at me,” Jones says. “It was unbelievable.” The calls were so vicious he thought about killing himself. “I pounded on my bed, cried, got a pistol out, made a list of pallbearers.”

When Jones complained to the New York attorney general, however, he was told the state could take no action “because your complaint basically involves a disagreement between you and the merchant regarding what occurred.”

The Company Store

The modem poverty industry exercises awesome power over the lives of working-class and minority borrowers. It may not control the poor as completely as the company store once dominated coal miners, or wealthy planters tyrannized sharecroppers. But the principle is the same: The company makes money while those who work for a living sink deeper and deeper in debt.

Activists agree that fighting big businesses that profit from the cycle of debt will take intense research and organizing. “It’s not local slum lords that are doing the damage,” explains Marty Leary, research director of Union Neighborhood Assistance Corp. “It’s corporations that are unaccountable, mysterious — and somewhere else.”

And growing bigger every day. Many now reach across the nation — and around the globe. Jack Daugherty of Cash America intends to use Wall Street respectability and bank financing to expand his Southern pawn empire to every state in the union. Beyond that, he dreams of adding more international holdings to the 27 pawn shops his company already owns in Great Britain.

“We’re looking at Europe,” Daugherty says, his voice rising with excitement. “Canada. Australia. New Zealand. Russia. South Africa. It’s the world — worldwide.”

“A Brutal Bunch”

Richard Bell worked as a bill collector in Texas for over a decade before quitting to become a consumer advocate. In this excerpt from his testimony before the House Subcommittee on Consumer Affairs, he describes how the industry operates.

One day at work, I was doing the usual, making phone calls and screaming at the mother of a person who owed money to my client. After I repeatedly slammed the phone on my desk, I looked up and saw my 18-month-old son staring at me. I had brought him to my office, and he was stunned at what he saw his father doing. I will never forget the look of terror on his face. My son wouldn’t talk to me for a long time after that. It was two days before he would sit on my lap again.

After that day, every time I got back on the phone and started yelling at a consumer, I saw the image of my son’s face filled with terror. My son and my conscience got to me. I left the industry and vowed to help clean it up.

This nation’s bill collectors are a brutal bunch. I know. I worked for over 19 different agencies. At some, I held management positions or trained collectors. I have worked for some of the largest companies in the industry, including American Creditors Bureau, Debt Collectors Incorporated, and G.C. Services.

While I worked in Texas, the consumers in 90 to 95 percent of my accounts were out of state. Texas has no licensing for bill collectors, and creditors from all over the country use bill collectors from states with little regulation or enforcement.

Initially, when you get a file from the creditor showing that someone owes them money, you call the consumer. If you cannot get ahold of the consumer, you call the references the consumers provided in their application and frighten them into divulging the whereabouts of the consumer.

Parents are the first line of attack. They always know where their kids are, and they are often listed as references. Since they are usually reluctant to divulge information about their children, bill collectors say something like:

“I’m with the investigations unit of Walter County, we are investigating a gang of thieves and I do not know what this is about Ma’am but your son has been implicated. And, by the way Ma’am, if that stereo that is missing is in your home, you may be aiding and abetting a crime. Like I say, I don’t have all the information but this is urgent! Have him call me right away.”

After being frightened like that, it’s easy to get the elderly to pay their children’s bills. But since so many elderly are on a fixed income, they often do without needed medical care, heat, or food as a result of paying collection agencies.

When I would get called back, I would answer the phone: “Investigations” or “Law Office” or “Legal Department.” Then I would likely say:

“Hello, Mr. Smith? You live at 500 Elm Street don’t you? The client has placed a delinquent account with a collection agency. The agency has forwarded me the affidavit requesting criminal investigations, as well as capital gains tax fraud. Charges will be filed, according to federal and state codes. The bond has not been set, the warrants have not been issued. At this point, I believe the client is willing to forgo this procedure provided you’re prepared to send the balance of your account by Western Union or overnight delivery to the collection agency. If I receive a call by 1700 hours tomorrow and find out you have paid this bill, I will go to the courthouse and have the judge sign a Stay of Execution Order and your criminal record will be expunged.”

The trick that bill collectors have mastered is sounding helpful yet threatening at the same time. This technique silences those who would likely complain about a collector who screamed and insulted them.

One of the biggest myths is that people who don’t pay their bill are deadbeats. Approximately 96 to 98 percent of consumers truly want to pay their bills. Every consumer tries to work out something with their collector, some form of monthly payment. This is not profitable for the collector. Collectors are only interested in immediate payment in full.

The philosophy of the vicious bill collector is that the more trouble he creates in the consumer’s family, the quicker the bill will be paid. We would tell kids their father was having an affair, or tell the consumer that they could lose their children to local child welfare agencies. This is especially successful when used against single mothers.

Collectors who turn to illegal and predatory tactics to collect debts have the clear consent of agency management — and more than likely the consent of the creditor. My research shows that many of the creditors do not check with the Federal Trade Commission or state attorney general about the agencies they use. Why? Because the most brutal collectors provide creditors with the greatest return. They are interested only in the bottom line.

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)