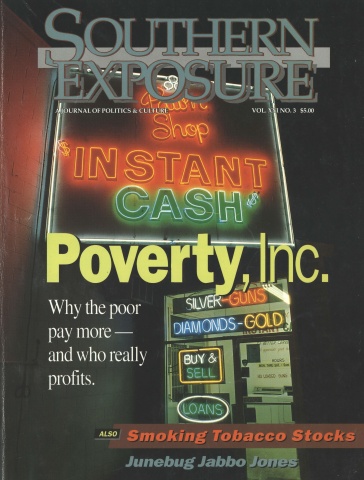

Poverty, Inc.

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Dot Woods used to be a teller at the old Fidelity bank on the corner of Driver and Angier in East Durham, North Carolina. “It was such a beautiful building,” she recalls. “It was so old-fashioned, with high ceilings and marble floors. It even had a balcony in the lobby.”

That was back in the 1950s, when the neighborhood bustled with life and local merchants prospered in the rows of red-brick shops that line the streets. Today the storefronts look worn and tired — and the imposing columns of the old bank now mark the entrance of East Durham Jewelry & Pawn.

Second-hand tools and stereos line the counters where local residents once made deposits and balanced their checkbooks. A sign next to a display of rifles announces, “Absolutely No Loaded Guns.” Customers can hock their belongings in exchange for loans that carry annual interest rates of 240 percent.

The bank-turned-pawn shop underscores a trend in inner-city neighborhoods and small towns across the nation. As mainstream banks have closed their doors in poor and working-class communities, unregulated money changers have moved in. Pawn shops and check cashers, rent-to-own stores and used-car dealers, finance companies and trade schools — all target the poor for profit, charging exorbitant fees and interest for basic services.

Credit is the lifeblood of the community. Loans enable people to invest in their future by buying a home, to get the education they need to find decent jobs, or to buy a car that will carry them to and from work, school, the store.

But those paths out of poverty are also the means by which financial predators now push people deeper into debt. Fraudulent home-loan deals, trade-school scams, and used-car rip-offs keep people poor — and enrich the businesses that lend them money.

The poor have always paid more — for groceries, household goods, insurance, and especially for credit. As more Americans sink into poverty or succumb to the lure of easy debt, however, the businesses that target them are bigger and more powerful than ever. They are increasingly owned by corporate giants like Ford, Westinghouse, and American Express, and underwritten by the same banks that refused the poor credit in the first place.

The poor aren’t the only ones hurt by predatory lending. As corporations pour money into pawn shops and other “fringe banks,” entire communities suffer. Hometown banks and S&Ls close their doors. Small businesses find it harder to get loans. Middle-class consumers, forced to borrow to pay their bills, find their credit ruined and their savings sucked dry. The entire nation becomes a financial ghetto, where usury is a trap, and bankruptcy the only escape.

Many who get in over their heads have few economic options, and lack the financial sophistication to avoid loan scams. But millions of well-educated consumers have also fallen prey to intricate schemes.

“We are convinced that the proverbial Philadelphia lawyer could not explain all the legal issues raised by these confusing documents,” said a Florida court after reviewing the paperwork on one 690-percent loan from a pawn company called Quick Cash. “This transaction could easily be the feature question in a difficult law school exam.”

This special section of Southern Exposure explores how the poverty industry works — and how average citizens are fighting back. Beating the credit predators won’t be easy. Consumer laws won’t solve anything unless they are accompanied by grassroots activism that educates people about their rights and develops non-profit alternatives that offer credit at a fair price. Without real reform, consumers will continue to sink deeper into debt.

Lilly Hunter tried to pull her four children out of poverty by enrolling with a trade school in Roanoke, Virginia. “Drive big trucks,” read the ad. “Make big bucks.” But the promise of a job proved to be a lie — and Hunter wound up $3,600 in debt.

“This was me and my family’s way out,” she said. “I was proud of myself for doing something. And my kids was, too. But really all they got was their heart broke.”

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.