This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Juanita Shorter looked on as her classmates plunged used, contaminated needles into each other’s arms. Their teacher stood by silently.

Shorter had come to Connecticut Academy, a private trade school in downtown Atlanta, to train as a medical assistant. The school’s recruiter had promised her a free, government-funded education that would prepare her to work in a hospital or doctor’s office.

Instead, she found a school where needle-sharing was common and waste disposal was cavalier at best. “We was fooling around with needles, blood,” she says. “We could throw the blood in the garbage cans. We could discard urine anywhere. I wouldn’t let them inject me with the same needle, though. I knew that needle was contaminated.”

Despite her revulsion, Shorter stuck with the seven-month program. The school, after all, was accredited. And with the prospect of a good job to support her two children, “I wasn’t ready to give up.” So she sat up nights in her trailer memorizing medical terms until she cried. She bought colored markers and wrote the words over and over until she learned them. She even brought home clean needles to practice on her boyfriend.

It wasn’t until she graduated that Shorter realized the training was useless. No hospital would hire graduates with Connecticut Academy diplomas. One doctor “told me he could not hire me with that,” she recalls. “He said they’d throw him a malpractice suit quick.”

During the past decade, thousands of poor and working-class Southerners like Shorter have been defrauded by private trade schools that lure them with promises of jobs — and then saddle them with big debts. In the process, the schools function as cash machines for big banks, enabling them to pocket billions of dollars in student loans guaranteed by the federal government.

Less than a month after Shorter graduated, a woman from First American Savings called her and ordered her to begin repaying more than $5,000 in student loans. “What loan?” Shorter replied. “I didn’t make a loan. I filed for a grant.”

The bank said otherwise. Without telling her what she was signing, Shorter learned, Connecticut Academy had tricked her into applying for a student loan.

Before long, the lender turned her account over to a collection agency, which called her four or five times a day, sometimes as late as 11:30 p.m., threatening to sue. Living on food stamps and $235 a month in federal aid, Shorter couldn’t repay. The collection agent persisted. “She would ask me, do I have a car, do I own my house, how much furniture did I have?”

Shorter continues to look for work, without success. “To be honest, my future is at a standstill,” she says. “I wanted to show my kids that you can always better yourself. But you look at my situation. What I’m showing them is: Your mama went out there and did the stupidest thing in her life. She listened to someone who was supposed to be trustworthy. She worked hard to get a diploma, and she can’t even stick it up on the wall because it makes her so mad, because it’s no good whatsoever.”

Hole in the Wall

With public job training programs slashed and jobs hard to come by, private trade schools have become a big business. As of 1990, the last year for which the U.S. Department of Education has figures, more than 4,500 accredited for-profit trade schools enrolled 1.4 million students. The schools promised them careers as beauticians, bookkeepers, medical assistants, computer operators, truck drivers, secretaries, and security guards.

The schools take credit for training an entire class of workers. “If these schools were to come to a halt, so would America,” says Stephen Blair, president of the Career College Association, an industry trade group.

Whatever their value, the schools have flourished on government handouts: More than 80 percent of their students get federal grants or guaranteed loans. In fact, trade schools collect almost 20 percent of all federal student loans — some $2.5 billion in 1991 alone.

Some trade schools do offer solid training and good job prospects. But many have used shady salesmanship and outright fraud to exploit the dreams of the poor.

The trade school swindle is relatively simple. Across the South, hundreds of schools advertise on daytime television, and their recruiters comb poor neighborhoods and welfare lines looking for new students. “Do you love money — the feel of it, the smell of it, the way it sounds when you crunch it up?” asks one TV commercial. “If green is your favorite color, we have a perfect job for you. Become a bank teller and get paid to work with money. . . . You’ll be rolling in the dough before you know it.”

Lured by promises of a free education and a guaranteed job, students come to the school, take a token admissions test, and sign some financial aid forms. It is only when they get to class that they realize it’s a sham.

In Miami, a respiratory-therapy school was equipped with broken machines; students had to enter through a hole in the wall of an X-rated tape store. In Albany, Georgia, a school charged more than $4,000 to train students as low-wage nursing-home aides — while a nearby public school offered the same course for $20. In Florida, a chain of schools for travel agents spent more than half its budget on recruiters — and less than two percent on teachers and classroom materials.

Confronted by such scams, some students drop out. Others graduate, only to discover that their school has no job placement service. Many are hounded by banks and collection agencies to repay their student loans. They cannot get a job because their diplomas are worthless; they cannot go back to school because they have defaulted on one student loan and can’t get another. The disasters start spiraling.

When Kathy Walbert graduated from Connecticut Academy and found herself unemployable, she and her disabled husband needed money to eat. But with their wrecked credit, they couldn’t take out a loan against the modest house they own in East Atlanta. So Walbert hocked her wedding ring and a pistol at a pawn shop, and now she pays $12.50 a month — at 150 percent annual interest — to keep them from being sold.

“We don’t even have money to buy groceries with. We can’t even afford nitty-gritty. We’ve got $3 in the bank,” says Walbert. “I’ll tell you the truth: I wish I never went to the school. It really messed up my life.”

Phil Mebane attended a training session the school held for its recruiters. In an affidavit, Mebane said the director of admissions “made it clear that the school’s sole purpose was to make money by obtaining federal financial aid funds. It appeared that the school’s teachers were employed simply to keep the students entertained so that they would stay in school for at least six days — until the student loan check came in.”

According to Mebane, the admissions officer “said that the school did not care if the students learned anything.”

Michael Sykes, the director of the now-defunct Connecticut Academy, insists that he ran a legitimate school. The teachers, he said in a court deposition, “were dedicated to what they did and had backgrounds important to the fields.” Sykes acknowledges that health inspectors had cited the school for unsterile conditions and improper handling of medical waste. “It’s possible,” he said, “that someone got a little lax.”

The Truck Man

Trade school officials like Sykes aren’t the only ones who profit from the fraud. According to the Department of Education, banks make $1 billion a year processing student loans — earning a higher rate of return than what they make on auto loans, home mortgages, and government securities.

Typically, a school bundles up batches of loan applications and sends them to a lender. Since the government guarantees the loans, the bank has no incentive to check out a student’s credit or a school’s reputation. The lenders advance money to the school, confident they’ll get their money back, no matter what.

Even when students get cheated, banks make money. Lenders accused of profiting from trade school fraud include Florida Federal Savings and Loan, Crestar Bank of Virginia, Wachovia Bank of North Carolina, and Charleston National Bank of West Virginia.

The banks like it that way. “It’s very hard for a banker, operating at arm’s length in making loans, to assess just how good or bad a particular academic program is,” says David Hardesty, an attorney for the West Virginia Bankers Association.

For years, the federal government made at least nominal attempts to ferret out the swindlers. But when Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, he began his crusade to dismantle the Department of Education. Over the next six years, the number of government reviews of trade schools dropped from 1,058 to 372. At the same time, the amount of federal aid skyrocketed.

“It was like throwing money into an open field,” says Brian Thompson, a spokesman for the Career College Association.

The abuses skyrocketed too. In Nashville, Tennessee, a beauty-school owner named Tommy Wayne Downs applied for — and received — $175,000 in loans for imaginary students. He got caught only when his secretary accidentally tipped off the federal government.

Downs began his career as a recruiter for a home-study course in truck driving. He was so eager to recruit students that he would take them to pawn shops to sell their belongings for tuition down payments.

“I focused my attention on welfare offices, unemployment lines, and housing projects, where I became so familiar that some of the residents referred to me as the ‘truck man,’” he told a U.S. Senate panel. “My approach to a prospective student was that if he could breathe, scribble his name, had a driver’s license, and was over 18 years of age, he was qualified.”

“What you sell is basically one thing,” Downs added. “You sell dreams. And so 99 percent of my sales were made in poor black areas.”

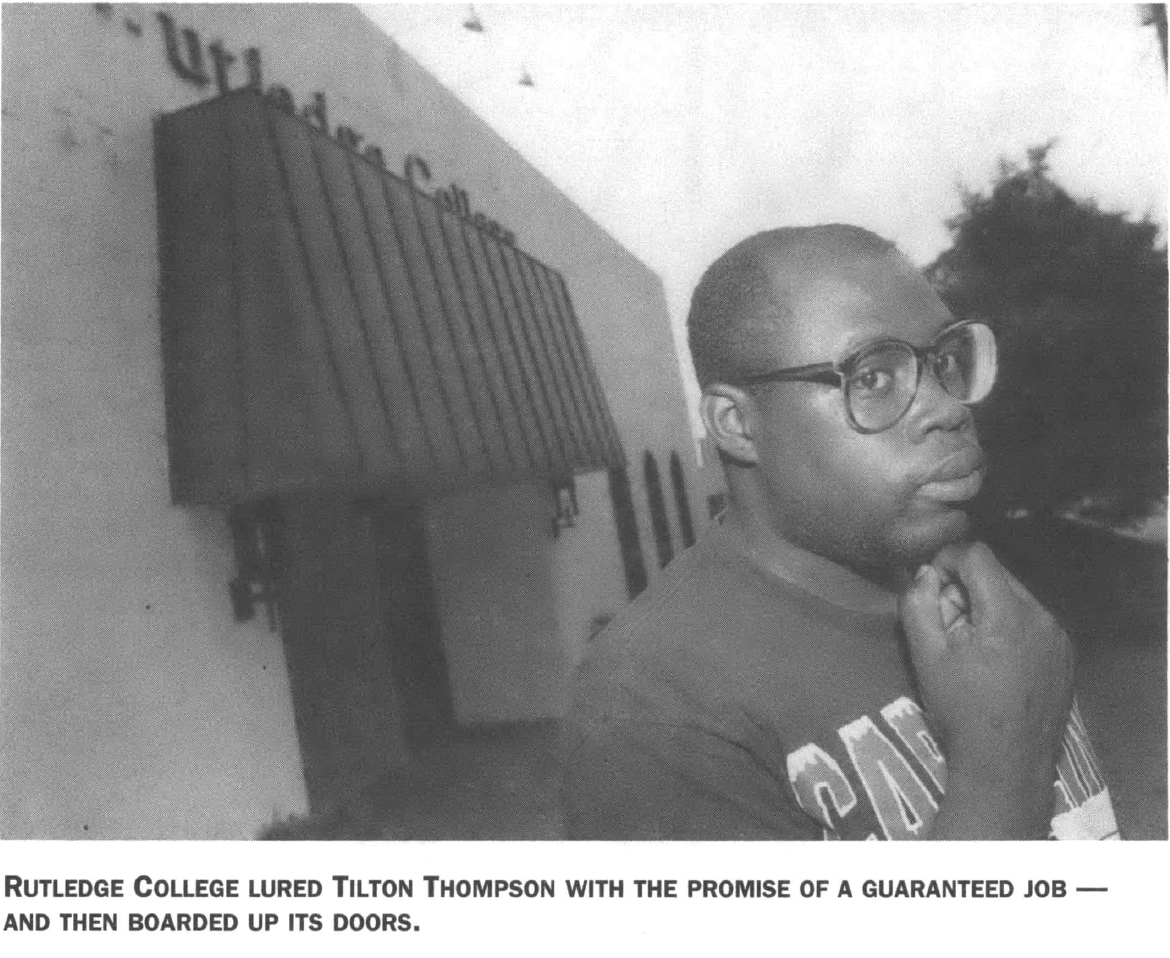

Many schools began accepting students who couldn’t possibly finish the course work — but who could help rake in guaranteed loan money. In Durham, North Carolina, Rutledge College lured a mentally retarded man named Tilton Thompson with promises of special tutoring and a guaranteed job. He received neither. Thompson got his loan canceled only after a Legal Services attorney threatened to sue.

The recruiter “said I would be guaranteed a job,” recalls Thompson, who was already enrolled in a training program with Goodwill Industries. “He said I would get a grant. He never mentioned the word loan. He said the government had set aside this money for young people like me to go to school, and if I passed it by I was letting go of an opportunity.”

Like many trade schools, Rutledge College was no fly-by-night operation. For years it was part of a nationwide chain of 27 schools owned by George Shinn, owner of the Charlotte Hornets pro basketball team and a major donor to Republican candidates like South Carolina Senator Ernest Hollings and former North Carolina Governor Jim Martin. Banks like Manufacturers Hanover Trust were pleased to do business with his trade schools — even though they boasted a student dropout rate of 20 percent every six weeks.

“It’s a rip-off for poor people,” Rutledge graduate Vivian Green told The Charlotte Observer. “It feeds poor people’s dreams — people who want to do better.”

“Fraud and Abuse”

Although trade school fraud occurs nationwide, widespread poverty in the South has made the region a particularly fertile territory for the scam artists. In Virginia this past May, the attorney general charged Commonwealth Educational Systems with encouraging students at five business schools to forge spouses’ signatures on loan documents, falsifying records to collect loans from dropouts, inflating the credentials of instructors — even telling prospective students that the eight-year-old school was founded in 1889.

“Where the most vulnerable exists, that’s where there seems to be the most ripoffs,” says Jon Sheldon, an attorney with the National Consumer Law Center.

As early as 1985, the U.S. Government Accounting Office charged that two thirds of trade schools were lying to students — overstating job placement rates for graduates, for example, or offering “free scholarships” that did not reduce tuition.

It took Congress until 1990 to do anything about it. That year, more than 40 percent of all trade school students defaulted on their loans. “Usually it’s the students who have not gotten an education who are most likely to default,” says Darlene Graham, a North Carolina assistant attorney general. All told, unpaid loans cost taxpayers $2.9 billion last year — or 44 cents out of every dollar spent on federal student loans.

A Senate subcommittee chaired by Georgia Democrat Sam Nunn investigated and found “fraud and abuse at every level” of the student loan program — particularly among trade schools. In response, the Department of Education cut off aid to 828 schools with high default rates, forcing many to close. And Congress passed a law toughening accreditation standards and forgiving loans to some defrauded students.

Brian Thompson of the Career College Association insists the new measures have eliminated abuse by forcing the worst offenders to shut down. “Granted, there were abuses in the past,” he says. “All of that has been changed. All of that has been corrected.”

But while the feds can now cut off aid to outlaw schools, it may take years to shut them down. “That’s a slow way of getting at fraud,” says Sheldon of the National Consumer Law Center. “You need day-to-day policing.” What’s more, thousands of students still owe money for the worthless education they were sold before the new law took effect.

Landmark Case

Tim Tipton wanted to spend his life doing more than working in a tool-and-die shop. He saw his future in his hometown paper in West Virginia.

There, in an advertisement, Northeastern Business College promised to train students in computer-aided drafting. It seemed like a perfect career move: “I figured with my background, working with blueprints, I shouldn’t be bad off.”

But once he signed the papers for a $3,500 student loan, he learned the school didn’t even have computers. “When we went in, they gave me shit that I could have bought for 30 or 40 bucks at any bookstore,” he says. The only equipment was a “very basic manual drafting kit,” and the textbooks were outdated. “Any kid in the eighth grade can get into any vo-tech school and get those books or better,” he says.

Tipton tried to stick with the program. When he complained about the poor equipment, school officials claimed new machines were coming. It didn’t take him long to figure out the computers would never arrive, he says, and three months after enrolling, Tipton dropped out. Soon after, Northeastern Business College closed down.

When Charleston National Bank started hounding Tipton, he contacted the Appalachian Research and Defense Fund, a legal-aid group based in Charleston. That’s how he became the lead plaintiff in a landmark case involving trade schools.

“A lot of people have a misconception of West Virginians being hillbillies,” Tipton says. “I wasn’t one of them. I knew right off I was defrauded, I was misled, I was fried.”

Since the school had already closed, it couldn’t be sued. So Tipton’s attorney, Dan Hedges, took on some even more powerful institutions. He sued a slew of banks and S&Ls for ignoring the fraud while raking in profits. He charged the Department of Education with slacking off on inspections and allowing schools to regulate themselves. And he accused the Higher Education Assistance Foundation (HEAF), a private group that insures student loans, of collecting fees without supervising schools or banks.

“It’s not just the ripoff artists,” Hedges says, “it’s the government that sanctions it.”

The banks and their insurer contended they shouldn’t be expected to check out the schools. “I am not about to defend certain of these schools. There may have been fraud going on. I don’t know,” says HEAF attorney Wendie Doyle. “The fact is, the borrower made the choice to go to the school. If we were to be subject every time a borrower is dissatisfied with his education, I don’t think there’d be much of a loan industry.”

But a federal court in West Virginia ruled that banks can be held liable for acting in partnership with fraudulent businesses. The suit was eventually settled out of court. Tipton and three of his classmates got their debts canceled, and Hedges plans to file suits on behalf of 100 other students from Northeastern Business College.

Profits vs. Training

Students in other states, including Virginia, Georgia, Texas, and Florida, have filed similar lawsuits. Juanita Shorter has become the lead plaintiff in a class-action suit involving former Connecticut Academy students.

LaRonda Barnes, the Atlanta Legal Aid attorney who filed the suit, hopes the spate of lawsuits will give pause to educational predators. But she knows that court cases alone won’t end the scams as long as the loan system offers easy money instead of adult education.

“Once you put the profit element in there,” Barnes says, “you’re running the risk that people will be doing this only to make money.”

Others agree. “It’s a ridiculous system to take kids who are very unsophisticated about a lot of things and give them a sea of loan papers from people who pull them off a welfare line,” says Jon Sheldon of the National Consumer Law Center. “Why is the federal government juicing this as a way of training people?”

The government has taken some steps to reform the system. In August, Congress passed a law that will take 60 percent of the student loan business out of the hands of banks — lending the money directly to students, without going through commercial lenders. In addition, the Department of Education now says banks can be held accountable for fraud committed by trade schools.

Sheldon and other consumer advocates say the government needs to go even farther, establishing uniform accreditation standards for trade schools and performing the type of surprise inspections that restaurants and other businesses routinely face. The government should also encourage real job training by contracting with businesses or nonprofit groups to provide training in targeted fields where jobs will be available, supporting community colleges that hold classes in housing projects, and providing counseling to assist students in making the right career choices.

Without such community alternatives and tougher regulation, trade schools and the banks that finance them will continue to profit from fraud. “Were I released from prison tomorrow, I could go out and do the very same thing again,” says Tommy Lee Downs, the Nashville beauty-school operator serving time for fraud. “I mean, you are talking about the ability to steal unfathomable amounts of money.”

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)