This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Consumer advocates say that shackling financial predators with tougher legislation won’t be enough to stop lending abuses. Poor and working-class communities need alternative sources of affordable credit — ones that place people over profits and provide money to support grassroots economic development.

Across the South, citizens are working to create a variety of homegrown institutions that provide hope and economic stability to their members. Consumers who have been ripped off by credit scams are learning to stand up for their rights, creating grassroots groups to fight predatory lenders. Self-help groups are relying on sweat equity and creative financing to reverse years of apathy and decay. And “community development” credit unions are demonstrating how mainstream institutions — banks included — can serve impoverished communities without going bankrupt.

The Institute for Southern Studies is currently completing a yearlong assessment of community-based economic development in the region, detailing the history and organizing strategies of the movement. We’ll report on our findings in a future issue, profiling more of the many groups that are empowering ordinary citizens to take control of their own lives and communities.

Grassroots Organizing

Coweta County, GA.

Soon after Lora Kling moved her family into a new home in Coweta County, Georgia, their neighbors started calling them “the people with the lake.” That’s because every time it rained, knee-high water flooded their yard.

Inside the house, the pipes and toilets gave off odors and bubbling noises. Sewage from a bad septic line seeped into the basement.

The problems didn’t end there. The builders, Jimmy and Dennis McDowell, financed the loan on the house and then sold it to Fleet Finance, the Atlanta-based mortgage giant. For years, Kling says, Fleet refused to provide an accounting of the loan — or even verify that payments had been credited toward the mortgage.

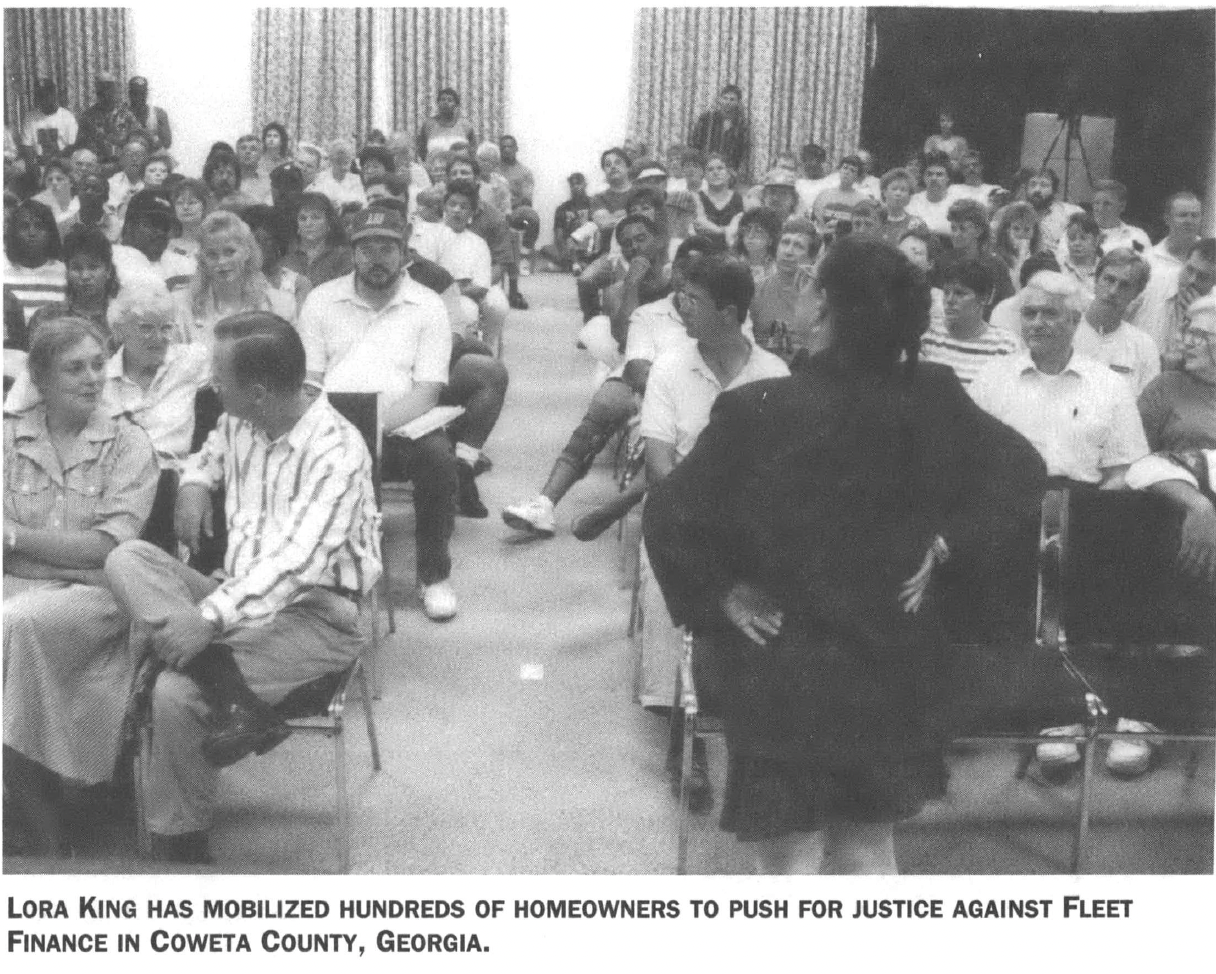

Kling fought back. She talked to hundreds of neighbors in the Peachtree Landing subdivisions that the McDowells helped build. Many had similar tales of brand-new homes with faulty construction and mortgages cloaked in mystery. She also confronted the McDowells, Fleet, and officials who supported them. Her grassroots hell-raising has sparked an uproar in this semi-rural county south of Atlanta — and has once again raised disturbing questions about one of the nation’s biggest mortgage companies.

Attorneys for the homeowners are preparing a class-action lawsuit accusing Fleet and the developers of working hand-in-hand in a scheme to cheat buyers. The companies deny any wrong doing.

Like the Klings, most of the homebuyers were blue-collar or middle-class people who had been denied conventional financing because of bad credit or a lack of credit history. They bought their homes through mortgages that were financed by the builders and then sold to Fleet.

When they fell behind on their payments, their homes were foreclosed and then resold — often to be foreclosed and resold again in a vicious cycle.

“The people who bought these homes were at great risk from the start,” Kling says. “Most were grateful because under normal circumstances they would never have owned a home. It is clear that this was a willful scheme to force people to fail. Frequent foreclosures make way for more mortgages and more money for the developers and Fleet.”

After two years of digging, Kling took her information to Diane Dawson, chair of the Coweta County Commission. Dawson says many homeowners told her that Fleet tacked on erroneous charges and late fees and made it nearly impossible for them to get information about their loans. Meanwhile, Dawson says, the builders refused to fix construction problems. Many buyers were forced to spend thousands of dollars for repairs, pushing them deeper into a financial hole — and often into foreclosure.

Fleet officials say they owned about 400 McDowell mortgages, but sold many of them back to the developer because of incomplete paperwork. Fleet says it no longer does business with McDowell.

William Brennen, an Atlanta Legal Aid attorney who has been investigating Fleet for years, says the Coweta County case mirrors others across the nation. “Every time Fleet gets caught doing something illegal, they say they’re stopping,” he says. “But that’s like saying Charles Manson has stopped killing people — it doesn’t do the victims any good. Fleet only stops after they get caught.”

The efforts by Kling and Dawson have prompted the Georgia Office of Consumer Affairs and the U.S. Justice Department to investigate. The two women wrote a 40-page report to federal officials that includes charges that county inspectors were paid off by the developers to overlook building-code violations in the subdivisions.

In response, 23 people named in the report filed a $50 million lawsuit accusing Kling and Dawson of libel, invasion of privacy, and stalking. The women say the lawsuit is simply an attempt to silence them.

But they won’t be quiet. The problems with her home have transformed Kling from a private woman to a public figure. She has helped bring together hundreds of other homeowners who are pushing for justice. She ran for county commissioner, losing with a respectable 46 percent of the vote.

As Kling sees it, the choice facing her and other homeowners is simple: walk away and lose everything, or stay and fight.

“I’m too proud a person to allow someone to control my life,” she says. “I’m not going anywhere, so we decided to fight.”

—Adam Feuerstein

Consumer Education

Columbia, S.C.

Dorothy Garrick became interested in consumer issues after she lost her job and went into debt to pay her bills. She is now Southern regional director of the National African-American Consumer Education Organization and president of its local chapter in Columbia, South Carolina.

It’s hard to get help in hard times. Around 1985 I was terminated at the telephone company, and while my case was being arbitrated I was unemployed. It put me in a financial bind. So I had to try to get assistance with my utility bills and it was hard to find. Well, where would you go?

I was one of those consumers, I didn’t get involved. When you’re working, making a good salary, you think everything is okay until you hit rock-bottom. Then you go to these agencies and the people that they have at the front desk, they treat you like you’re less than a person.

The company didn’t have cause to terminate me, so I was rehired back to my same salary. But by then I had ruined my credit, because I didn’t know how to handle a creditor. It’s always hard to catch up. That’s why I feel that I’ll always be active in the consumer arena: I know what it feels like to be treated less than, because you don’t have.

I can see how easy it would be to get caught up in it, if you need to make a mortgage payment, or a car payment, and they say, “Okay, we’ll lend you money.” You know you’re paying almost 25 cents on the dollar in interest, but you feel the need is so great you have nowhere else to go. So you will borrow, borrow, borrow ’til you can’t borrow any more. Some of the scam artists, that’s a way for them to take your homes and your cars, and to own you where you never get out of debt. That’s why consumer education is so important.

I became interested in consumer issues and started attending conferences in Washington, D.C. with Florence Rice, who is now president of our national organization. There were times we went to conferences and there were just maybe two or three blacks, including Florence and myself. So we noticed there was a need. We don’t have enough people attending the conferences to spread the word in our communities.

Right now we’re still in the organizing process. Mainly we’re working out of our homes. We have about 20 members. We have people if you need ’em I can call on them. Some of them have been through the same thing I’ve been through.

We’re grassroots people. I have a job: I work 10 hours a day, four days a week. But I can do a lot along with the other volunteers. We can network and provide information in our spare time. We can schedule workshops and seminars for different groups, just empowering people to find the information they need.

It’s basically what we can afford out of our pockets, and friends who give money to help us with something. If we need some printing done someone will say, “I’ll give you some money to help you with that.” Or: “Give it to me and I’ll take it to my office and make you some copies.”

I’m also active in the Communications Workers union and the NAACP, so I can blend consumer education with other organizations I work with. My spare time is spent doing volunteer work. I was raised up with that — that you’re supposed to put back what you can into the community. I’d rather go to a meeting or a seminar than go to a party.

Local Development

Four Corners, La.

Five years ago, Irma Lewis remembers, Four Corners was a dying community. The hamlet set among the sugar cane fields of southern Louisiana was full of decaying clapboard homes. Many of its 400 residents — whose average income fell below $10,000 a year — saw little hope for the future.

“Four Comers was a place forgotten,” says Lewis. “But we’re on the map now. People know Four Corners exists.”

The people of Four Corners turned their community around by uniting to rebuild it. They’ve been inspired by a simple idea — neighbor helping neighbor to save their own homes.

The Southern Mutual Help Association, which has been fighting for the rights of sugar cane workers for more than two decades, came to Four Corners in 1989 with a proposition: It would bring in plumbers and other contractors to provide training. Residents, in turn, would pledge to pitch in and work until every house in town was renovated.

The 15 black women who attended that first meeting founded the Four Corners Self Help Housing Committee and began recruiting other residents. Together they pounded nails. They sliced through plywood with power saws. They sealed busted pipes. In all, they refurbished three dozen homes. Now the idea has spread to the neighboring communities of Sorrel and Glenco.

Lorna Bourg, assistant director of Southern Mutual Help, says that some Four Corners residents have been victimized by shoddy contractors. Although such abuse was not the impetus for the rebuilding campaign, Bourg says the self-help idea provides a grassroots model that could be transplanted to other towns and even urban neighborhoods as a way of heading off unscrupulous home-repair and second-mortgage companies.

To make it work, Bourg’s group has helped secure more than $750,000 in federal support. It has also worked with Iberia Savings Bank to arrange loans at one percent interest for home repair. So far 28 of 30 applications have been approved, with loans ranging from $500 to $17,000. No borrower has defaulted.

And Four Corners shows no signs of turning back. When Hurricane Andrew swept into Louisiana last year and destroyed much of what it had taken residents three years to accomplish, they simply started over and rebuilt their homes better than ever.

The storm blew one woman’s home off its piers. She was ready to call it a total loss and move away — until Irma Lewis told her to close her eyes. “I want you to visualize your house the way you want it,” Lewis told her. “Think about how you want it painted. Think about how you want your porch.” The woman closed her eyes. Soon she was smiling. Today, Lewis says, the house is back on its piers. “And it’s beautiful.”

—Mike Hudson and Bernard Chaillot

Community Credit

Mt. Vernon, Ky.

Dwight and Shana Mahaffey have been paying the Beneficial Mortgage Company $230 every month for four years to buy a mobile home and three-acre lot near Mount Vernon, Kentucky. Beneficial, a subsidiary of one of the largest consumer-finance companies in America, charges them 16.5 percent interest.

The Mahaffeys borrowed $15,000 from Beneficial in April 1989. Come next spring, the five-year note comes due — and they’ll still owe a final “balloon payment” of $13,713.

Fortunately, the couple has a better deal waiting for them: Central Appalachian People’s Federal Credit Union has promised to write them a loan at 10 percent interest. Central Appalachian will refinance some small consumer loans the Mahaffeys already have with the credit union and add them into a loan to pay off Beneficial. In all, the Mahaffey’s monthly debts will be cut in half.

Across the region, Central Appalachian and other “community development credit unions” are providing an alternative to hard-working people like the Mahaffeys who are often shut out by banks and charged painful prices by finance companies, pawn shops, and other lenders of last resort.

Community credit unions loan money to factory workers, the elderly, and welfare recipients at affordable rates — without tacking on insurance charges and other hidden fees. In the process, they have established themselves as grassroots centers of community pride, economic development, and consumer education.

There are an estimated 300 credit unions nationwide serving limited-income borrowers. Nearly half are in the South, and all are non-profit institutions owned and run by their depositors.

In many ways, these credit unions are the mirror images of banks. Banks drain money out of low-income and minority communities by taking deposits from poor neighborhoods and using the money to make loans to people in more affluent areas. By contrast, credit unions funnel money into low-income communities by making loans only to their members, and by attracting “non-member” deposits from corporations, foundations, churches, and other non-profits.

Bankers say loaning money to low-income and minority people is too risky. Credit unions across the region are proving them wrong:

▼ Throughout North Carolina, the Self-Help Credit Union offers mortgages to low-income home buyers and provides credit to non-profit groups, employee-owned businesses, and other agents of social change. Founded in Durham a decade ago with bake-sale proceeds, Self-Help now manages $40 million in assets. It was recently touted on Capitol Hill as a model that could help President Clinton live up to his campaign promise to create 100 “community development banks.”

▼ In the northwestern panhandle of Florida, the North East Jackson Area Federal Credit Union sits in a trailer in Pearl Long’s side yard, surrounded by fields of peanuts. Its members — many of them independent African-American farmers — pool their money for crop loans and used-car financing.

▼ For hundreds of miles around Berea, Kentucky, Central Appalachian People’s Federal Credit Union lends out $ 1.2 million a year to poor and working-class borrowers. It has 1,500 individual members, as well as more than 40 member organizations that serve as branch offices, including schools, housing projects, and even a plastics factory.

“They Work So Well”

Despite their successes, such “limited-income” credit unions represent barely two percent of the 13,000-plus credit unions nationwide. “It amazes me there aren’t more of these, because they work so very well,” says Mike Eichler, a community organizer in New Orleans for the non-profit Local Initiatives Support Corp.

They also remain tiny compared to banks and employer-based credit unions. In 1991, these poor people’s institutions averaged less than $2 million in assets, compared to $17 million for all credit unions.

History — and government intransigence — have something to do with why there are so few of them. Grassroots credit unions first emerged in Southern black communities during the 1940s, enabling those cut off by mainstream banks to pool resources and borrow money. The federal government copied the idea during the 1960s, creating at least 400 as part of the War On Poverty.

The feds invested lots of money in setting them up, but did little to ensure training and stability. “By 1967 or 1968, they pulled the rug out completely,” says John Isbister, an economist at the University of California in Santa Cruz who has studied credit unions. “They just stopped funding them — and most of them just failed.”

One hundred or so survived, but the casualty rate from that haphazard effort provided a ready excuse for Republican-appointed regulators who didn’t care much for the idea of credit unions for the poor. During the 1980s, Isbister says, federal officials repeatedly held back federal loans to grassroots credit unions and limited the amount of “non-member” deposits they could take in. In the late 1980s, the savings and loan debacle — created largely by Reagan-era deregulation — offered yet another rationale for hindering the growth of community credit unions.

Many have had a tough time of it. Federal regulators have repeatedly threatened to shut down the North East Jackson credit union in Greenwood, Florida. Created during the 1960s to support civil rights activists denied credit by the local white power structure, the credit union earned only 35 cents in interest during its first year. By 1980, its loan delinquency rate had soared to 30 percent. But under the leadership of Pearl Long, a retired teacher whose equipment shed housed the credit union for a while, the lender has squeezed its late-payment rate to 2.5 percent — close to the national average of 1.6 percent.

In Kentucky, Central Appalachian has also cut its late-payment rate in recent years and now writes off barely three percent of its loans as a loss. Marcus Bordelon, a former banker and VISTA volunteer who manages the credit union, says the lender works with borrowers who fall behind, stretching out payments and helping them get on their feet.

Bordelon says the credit union is also there for anyone who gets into trouble with for-profit lenders. One member who didn’t know Central Appalachian offered loans in addition to savings accounts went to Kentucky Finance Company to borrow $500. The lender made him put up his car as collateral, and then added on $300 in insurance, car club membership, and other fees. At 36 percent interest, the borrower would have owed more than $1,000. He escaped by refinancing with the credit union at 16 percent — with free credit insurance and no collateral required.

Another credit union member signed up to “rent to own” a TV and stereo from Curtis Mathis for $37 a week. After three months, she realized she was going to pay $4,000 for items priced at $1,700. When her phone and cable hookup were cut off, she went to the credit union and borrowed money to buy the things outright.

Dwight and Shana Mahaffey have used loans from Central Appalachian to cover hospital bills for their children and repay a student loan that put Shana through business school. “Anytime I want anything,” Dwight says, “all I have to do is go to the credit union.”

Dwight, who works as a manager at a McDonald’s and helps run his parents’ sporting goods store, is also using the credit union to get out of the 16.5-percent mortgage on the trailer and land he and Shana bought from her parents. His in-laws already had a mortgage from Beneficial, and the Mahaffeys thought it would be convenient to stick with the same lender.

“The thing with finance companies, they make it so easy,” Dwight says. “Somebody needs some money real fast, they go into Kentucky Finance or Beneficial and in 30 minutes walk out with a check. They don’t care what the interest rate is.”

To educate consumers about their financial options, Central Appalachian holds workshops and includes “scam alerts” in its newsletter. Credit union advocates also hope federal officials will expand access to affordable credit by providing seed money and fairer rules governing financial institutions. President Clinton, they point out, could have been talking about grassroots credit unions when he said before the election: “I think every major urban area and every poor rural area ought to have access to a bank that operates on the radical idea that they ought to make loans to people who deposit in their bank.”

Mike Eichler, the New Orleans-based activist, says credit unions don’t cost much to run, especially when other nonprofits and churches donate office space and staff. Most of the time and money goes into start-up — investing the leg work needed to drum up community support. Such effort, he emphasizes, brings results.

“I don’t think there’s apathy about the fact that people are stuck with having to pay 30 percent for a loan,” Eichler says. “It’s just a matter of convincing them through organizing that there is an alternative.”

— Mike Hudson

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)