This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

I was around in the early 1960s, during the heyday of the civil rights era. I remember the excitement at feeling that we were on the edge of history, that we were in the process of creating a more humane society. I remember the sense of pride we felt as we stood up and challenged racial discrimination and oppression in the South, eventually seeing our faith materialize into national public policy. As I sat-in in Memphis and registered black voters in Mississippi, I knew both the fear and excitement, the anxiety and exhilaration of challenging the entrenched forces of racial apartheid in the South. I knew the feeling of being irresistibly caught up in the currents and cross-currents of a powerful history-making movement.

Representative John Lewis, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the early ’60s, recalled those days in the August issue of Emerge magazine. “You know,” he said, “whether it was sitting in or going on the Freedom Rides or marching for the right to vote or marching on Washington for jobs and freedom, you were part of something much larger . . . and you were involved in something that was exciting. We felt like the force of the universe was on our side. I think it’s good to be in Congress, but it’s no comparison, really. I don’t feel like I’m involved in a crusade here.”

Reading this statement brought to my mind how much less hopeful and confident I am today than I was during the ’60s. It caused me to wonder what took so much of the excitement out of my life, the sense of being involved in a “crusade,” of being “part of something much larger” than myself.

Not trusting my personal understanding of what went wrong, an associate and I picked up the phone. We called several current social activists and asked their opinions as to why the movement has lost its luster. Much of what we learned was not only exciting and encouraging, but extremely reminiscent of the ’60s.

We discovered that things are not nearly as gloomy as I had come to feel. We learned of dozens of dedicated and unsung people and groups around the country whose work is just as exciting as our activities were 30 years ago. They are just as convinced of the historical significance of what they are doing, just as empowered and liberated by it.

One of the people we discovered was Lillie Webb, a grassroots activist in Hancock County, Georgia. Webb criticized the “unbelievable stagnation” among established political leaders who insist on “doing things the way they did them 20 years ago.”

“The people have lost hope in the government” she said. “The government needs to be returned to the people. And the people need to accept the responsibility of government. The people are the government; but we no longer see ourselves as the government. We need to take the full responsibility for what’s happening to us, and not just give that responsibility to somebody else.”

Like other grassroots leaders we interviewed, Webb’s disappointment with traditional leaders has not caused her to despair. Instead, it has motivated her to take the lead in creating the Center for Community Development of Hancock County, which seeks to foster comprehensive, grassroots development in the area. This is her way of putting into practice her idea of returning the government to the people.

We also learned of Margarita Romo of Farmworkers Self-Help of Dade City, Florida, who for 14 years has been organizing farmworkers to create their own jobs, develop their own housing, and rescue their own children from teen parenting and inadequate education. The work of Romo and her organization is a model of leadership development, as numerous farmworkers have successfully moved into more responsible, influential, and financially rewarding positions.

Equally impressive were the organizing efforts of Virginia Sexton and Lisa Montelongo of the Cherokees of western North Carolina. The two women were instrumental in galvanizing the Native American community to successfully resist the siting of a waste disposal facility on their land. They also led a successful challenge to the exploitation of Indians by local tribal leaders and non-Indian owners of tourist businesses.

Particularly inspiring was the work of Phyllis Miller of the Mountain Women’s Exchange in Jellico, Tennessee. The group provides residents in eastern Tennessee and Kentucky with access to housing, adult literacy programs, and opportunities for leadership development, skills training, enterprise development, and cultural expression. Miller believes that “economic development in the mountains must come from within. We must help ourselves and each other if we are to survive.”

All of these activists appear to share the conviction that while citizens in a democracy may entrust the responsibility of government to elected officials, we should not permit ourselves to be removed completely from the process. They would no doubt agree with Lorna Bourg of Southern Mutual Self-Help in New Iberia, Louisiana. “Democracy functions best,” Bourg said, “when people are empowered.” Their shared commitment to this idea has enabled them to accomplish things many consider impossible. For this reason, I view them as harbingers of a powerful new grassroots uprising for democratic empowerment.

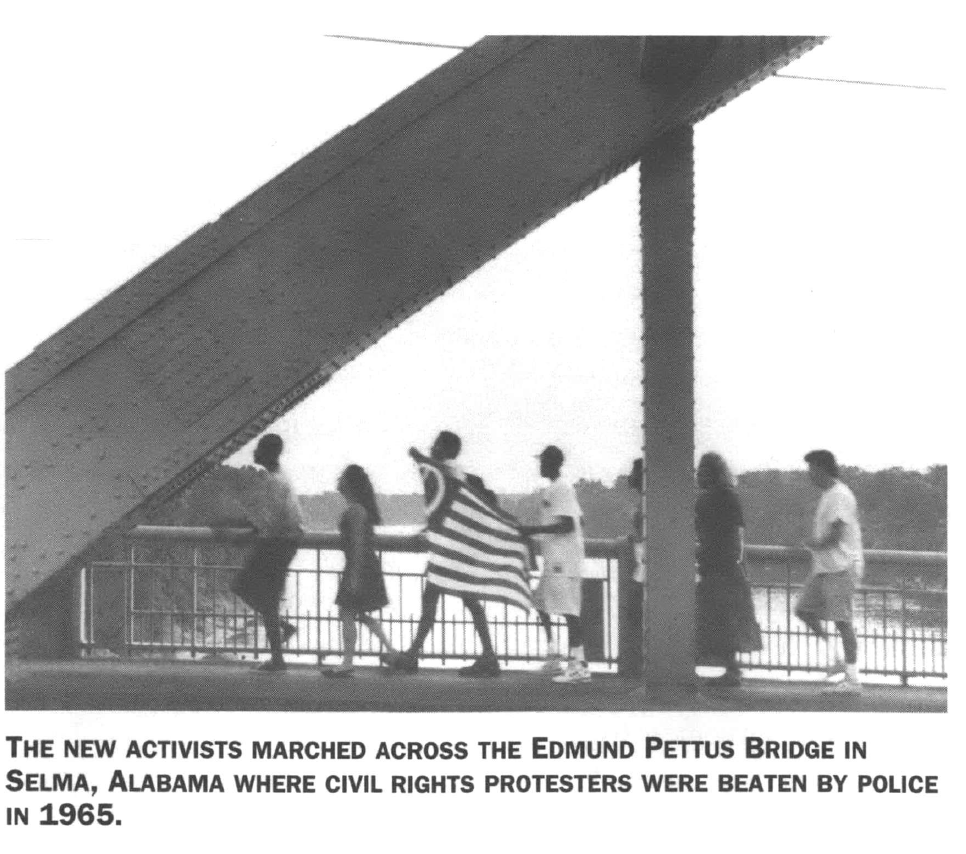

After speaking with these activists, I was startled by how much more positive they are about their work and achievements than most public officials and established leaders are about theirs. One organizer of this year’s march in commemoration of the 1963 March on Washington repeatedly called for the need to “inspire and revive the imagination” of the people, because their “hopes have been dashed.” I could hardly square this discouraging description of life in local communities with the optimism and excitement voiced by the grassroots activists I interviewed.

I cite their stories because I believe they address a critical need in our society — a need to give more public recognition to the success stories in our midst. The great lost opportunity of the recent March on Washington is that its organizers did not see fit to use it as a platform to give national visibility to the many harbingers of hope who labor out of sight.

Maybe giving them more attention at the March would have helped restore the faith of people who have become disillusioned by exposure to too much cynicism and despair. Maybe it would have reminded the rest of us who have succumbed to the pessimism and sentimentalism of our day that we have good cause not only to remember the past, but also to look to the future with renewed optimism and hope.

The exhilaration we felt in the ’60s stemmed from our direct involvement in a powerful movement in which oppressed people stood up and took personal responsibility for their lives, throwing off the shackles of racial domination. I am convinced that strengthening personal responsibility and community empowerment is in our time the first step we must make on the road to freedom. To liberate the oppressed, we must do what Lillie Webb and Margarita Romo and other activists are doing. We must engage the oppressed in liberating themselves.

After the March, columnist William Raspberry questioned the relevance of marching and demanding federal action to address the serious problems confronting African Americans today. “Apart from the demand for statehood for the District of Columbia, unspecified job creation programs, and support for health care reform, it was hard to see what Congress — or anyone else — was being asked to do,” Raspberry wrote. “The leadership — in curbing black-on-black crime, redeeming our communities, and rescuing our children — must be ours.”

This is precisely what community activists across the nation told me. Some are engaged in work which is highly successful in combating inner-city violence and rescuing children from lives of self-destruction. Among them are some of the most “inspired” and “inspiring” leaders I have ever encountered. Imagine how the March on Washington might have awakened people in the inner cities if the organizers had used it to give national visibility to gang members in South Central Los Angeles who have laid down their guns and taken up the task of ridding their neighborhoods of gangsterism, drugs, and violence. That would have been news worth shouting from the rooftops.

William Chafe, a professor of history at Duke University, captures the essence of this point in his book, Civilities and Civil Rights. “The surge for racial justice in North Carolina came not from the City Hall in Greensboro nor from the State Capitol in Raleigh,” writes Chafe. “It emerged from a thousand streets in a hundred towns, where black people, young and old, acted to realize their vision of justice long deferred.”

If we listen close enough, we can hear all over the nation and the world the escalating sound of internal, bottom-up empowerment rumbling in the countryside and the city streets.

Those who have ears to hear, let them hear.

Tags

Isaiah Madison

Isaiah Madison is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies. He became interested in community economic development when working as a lawyer in Mississippi. He handled cases for black farmers having difficulties holding onto their land and became involved with the Federation for Southern Cooperatives. (1994)