This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

Houston, Texas — A few words, delivered by his doctor, ended the addiction that led Everett Hanlon to smoke two packs of cigarettes a day for more than four decades.

“I think you got lung cancer there, fella,” his doctor told him over the phone. Hanlon, then chief executive officer of an electronics company, crushed out the cigarette he was smoking at the time and never lit another. Surgery, radiation therapy, and a fifty-fifty survival prognosis finally enticed him to kick the habit.

Yet lung cancer has done nothing to end a different kind of tobacco habit practiced by the very institution that treated Hanlon — the prestigious M.D. Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas.

For years, the school has invested its endowment in the stocks of tobacco companies — among them the makers of Camel, Marlboro, and Lucky Strike cigarettes, to name a few. Despite pressure to divest, current university investments in four top-ranking tobacco companies figure at just over $50 million.

Those mega-shares give UT System the dubious distinction of holding perhaps the largest investment in tobacco stocks of any public university. Former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop singled out the university during a campus speech as “kind of schizophrenic,” given its “world-renowned reputation for treatment of cancer at M.D. Anderson Hospital, where 10,000 people are there a year because they smoke.”

The stocks do not, however, qualify the school system as the only institution fighting cancer while trying to maximize returns on investments — even if that means supporting the makers of a product deemed by the Centers for Disease Control to account for 435,000 deaths a year, more than all illegal drugs combined.

Pension systems, retirement funds, and universities across the nation have been profiting from tobacco stock for years. A 1990 study by divestment activist Dr. Gregory Connolly details some $21 billion worth of tobacco stock held by state pension funds, insurance companies, investment funds, banks, college endowments, and academic retirement funds as of December 1987. The state of Texas alone holds nearly $400 million in tobacco stock, including $250 million in its Teacher Retirement System.

Connolly, head of the Massachusetts Office for Non-Smoking and Health, has also uncovered $7 billion worth of tobacco stock held by 37 state retirement funds. The California system contains some $500 million in tobacco investments — even though the state is considered a leader in anti-smoking initiatives.

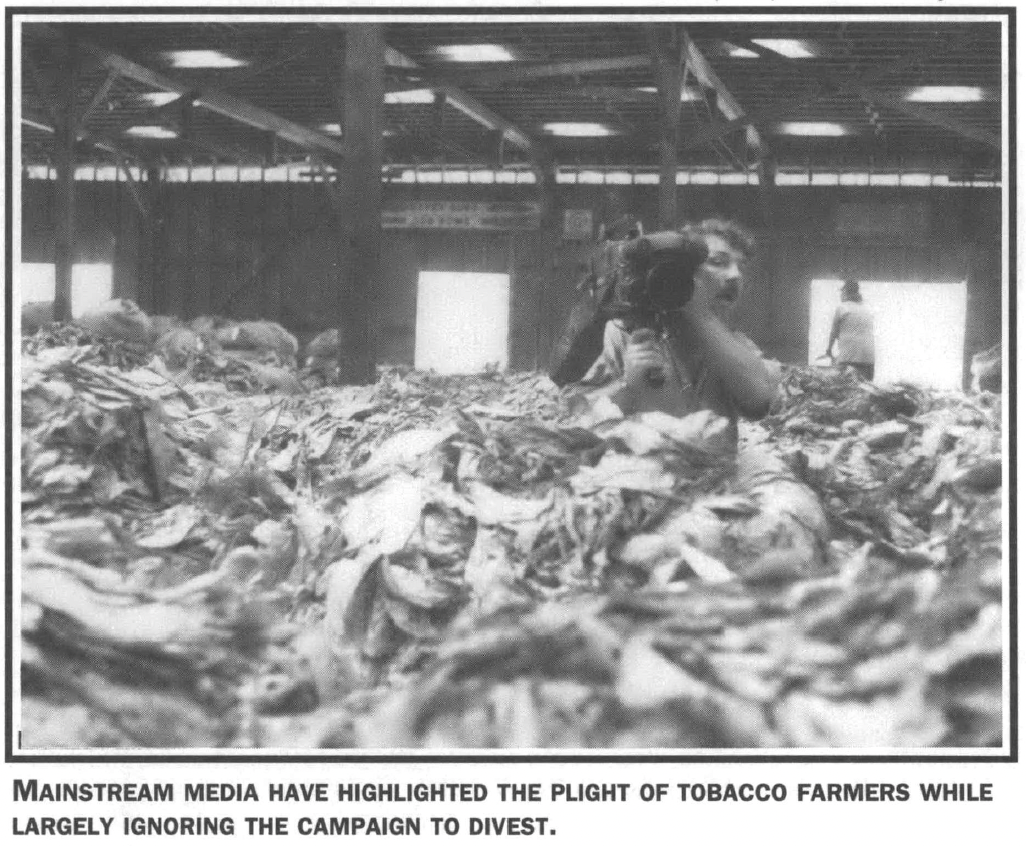

The glaring contradiction between public health and healthy investments has sparked grassroots efforts by students, doctors, and other concerned citizens to force public institutions like the University of Texas to divest. But the growing campaign to dump tobacco stocks has encountered opposition from university trustees, public officials, and money managers who would rather fight than switch.

“By and large, these are decisions made by a very small number of people behind closed doors,” says Connolly. “It’s like the FBI buying stock in the Mafia.”

New Patients

The justification most often used for resisting divestment is three-fold: that it breaches the “fiduciary responsibility” of an institution to maximize investments, that tobacco companies are most often diversified conglomerates, and that dumping stock would do little to change the tobacco industry.

Indeed, even Everett Hanlon, the 62-year-old cancer patient treated at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, offered that line of reasoning. Occasionally coughing as he spoke over lunch at a westside Houston restaurant, Hanlon said the mission of UT’s financial advisors is to maximize income. Period.

“Maybe it’s because I’m a businessman,” he said. “I’m a big boy. And I’ve known for more than 30 years that smoking ain’t good for you. And anybody that does smoke is a Goddamn fool.”

By contrast, divestment proponents argue that while tobacco conglomerates may be diversified, they get most of their profits from selling a product that is addictive and deadly. As anti-tobacco activists often point out, cigarettes are the only product on the market that harms consumers even when used exactly as intended.

But what impassions activists the most, what leads them to criticize their own employers, is the hypocrisy of institutions that claim to abhor the use of tobacco — all the while investing in companies accused of enticing children, targeting minorities, and hooking others on smoking.

“The only way these companies are going to continue to make new profits is to recruit new smokers,” says Dr. Joel Dunnington, a member of Doctors Ought to Care (DOC) and a radiologist at M.D. Anderson in Houston. “New smokers — and new patients.”

Dunnington cites a 1990 study by the Journal of the American Medical Association showing that two million children take up smoking each year — 5,479 a day, or 228 every hour. Another JAMA study found that 91 percent of six-year-olds can match cartoon character Joe Camel with a picture of a cigarette — making the grinning tobacco pusher nearly as familiar as Mickey Mouse. Since “Old Joe” was introduced, illegal sales of Camel cigarettes to children have skyrocketed from $6 million to $476 million a year.

Armed with facts like these, Dunnington and other members of DOC send letters urging institutions to divest, organize protests of museums and charities that accept money from tobacco companies, and ask organizations to divulge their tobacco holdings.

DOC, a Houston-based group founded and chaired by Dr. Alan Blum, has rallied grassroots support for anti-tobacco causes and has generated countless headlines, both locally and nationally.

A New Campaign

The group that went after Nestle and General Electric has now turned its sights on the tobacco industry. INFACT, a non-profit group based in Boston, announced the kickoff of its “third corporate accountability campaign” in May. “We’re putting the tobacco industry on notice,” said campaign director Kelle Louaillier. “We’re letting them know that there’s a huge group of people out there that want them to stop marketing tobacco to children.”

INFACT — which stands for Infant Formula Action Coalition — got its start in 1977 organizing a boycott against Nestle. It earned the spotlight again last year by winning an Academy Award for its documentary Deadly Deception, a devastating expose of General Electric and the nuclear weapons industry. The group credits the film and its seven-year consumer boycott of the company for GE’s decision to sell off its aerospace division last April.

GE officials claim the INFACT boycott had nothing to do with the sale, pointing instead to the shrinking defense industry.

Louaillier says it is “quite possible” that the war against the tobacco industry will include another documentary, but she declined to release specifics on the strategies, saying details will be forthcoming this fall.

INFACT has already launched a letter-writing campaign and has printed up buttons, stickers, and T-shirts. In keeping with its emphasis on stopping life-threatening abuses by transnational corporations, the group will focus on worldwide tobacco industry activities.

“Tobacco-related illness kills about three million people worldwide every year,” said Louaillier. “It makes you sick, basically. Tobacco is very profitable and this industry has a lot of money to throw around.”

The main thrust of the campaign will center on the marketing of cigarettes to children. According to the Centers for Disease Control, half of all smokers begin smoking regularly before 18 years of age.

Louaillier says the industry hooks 3,000 children a day to serve as “replacement smokers” for customers who quit or die from lung cancer or other diseases.

Walker Merryman, a spokesman for the pro-industry Tobacco Institute, denies tobacco companies have targeted children in their advertising. “We’ve been at the forefront of attempting to prevent not only the sales to youngsters, but their interest in smoking for many, many years,” he said.

Merryman said he had heard of INFACT, but was unaware of the tobacco campaign. “It sounds pretty redundant to me,” he said. "I haven’t heard anything in your comments that hasn’t been done already.”

But INFACT promises its campaign will provide consumers with concrete ways to fight the tobacco industry and safeguard public health. Although it has not yet called for a boycott, organizers say they may coordinate direct action against tobacco companies.

“If necessary, ” the group said in announcing the campaign, “public pressure will escalate through the use of economic disincentives and other strategies, including direct challenges to companies at their shareholder meetings next spring.”

— J.R.

For more information, contact INFACT, 256 Hanover Street, Boston, MA 02113, or call (617) 742-4583.

The group was instrumental in removing tobacco advertising from the view of television cameras at the Houston Astrodome and has relentlessly criticized Rice University for owning more than $40 million in tobacco holdings. DOC also uncovered crucial internal documents of tobacco giant Philip Morris, maker of Marlboro cigarettes, detailing strategies for donating $17 million to schools, charities, cultural groups, and hospitals in an effort to defeat anti-tobacco legislation.

According to Blum, who says he collects 100 pounds of materials each month on tobacco-related activities, the industry supports projects such as the arts and hospital research because “charity” buys a desperately needed commodity: respect.

“The tobacco industry wants image so badly,” he says. “The ceremonial, the ritual, and the symbols are all very important.”

Smoke Free?

Ron Turk, another anti-tobacco activist now on the Houston scene, was a college student at the University of Texas at Austin when he first became interested in divestment. After reading in The New York Times that Harvard University and City University of New York had dumped their huge tobacco holdings, Turk turned his attention to his own school.

He first got in touch with the Tobacco Divestment Project in Boston, the non-profit group that convinced CUNY to divest itself of $3.5 million in tobacco holdings in 1990. Turk also spent countless hours on the telephone with Dr. Phil Huang, a Harvard student and Rice University alumnus who developed radio ads critical of the Harvard holdings as part of a course on the role of the media in public health.

Those were heady times for divestment activists. Two prominent institutions had taken the moral high ground, placing the public good above private profits. The city of Pittsburgh, the Presbyterian Church, and the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation soon followed suit, and the Texas Board of Education narrowly rejected a move to sell $100 million in tobacco stocks.

“Tobacco is an addictive substance and causes illness,” said the Reverend Belle Miller McMaster, director of social justice and peacemaking for the Presbyterians. “We need to learn to deal with that so that it is not destructive.”

But for Turk and the University of Texas System, the road proved steeper. The Houston native formed a group called Students Against Tobacco Investments, but says he realized from the outset that he could not count on an active student lobby. “I didn’t spend any time on students because they were such a waste of time. It took me the same amount of time to get the support of the former surgeon general as the future dentists association.”

Moreover, then UT Board of Regents Chairman Louis Beecherl firmly opposed dropping the stock. In an October 1990 letter to Turk, Beecherl wrote that he did not believe “divestiture of tobacco securities is consistent with the obligations of the Board of Regents to nurture the long-term interests of the University of Texas System.” He went on to say that the board rejects the use of UT funds as a way to “advance social or political causes.”

Around the same time, however, regent W.A. “Tex” Moncrief wrote Turk to say he agreed with the student’s recommendations and thanked Turk for his interest in “an obnoxious habit that is a killer and should be eliminated.”

With months to go before the measure came before the board for a vote, Turk used the time to garner the support of alumni, faculty members, and public officials like Surgeon General Koop, the Texas Board of Health, and Governor Ann Richards.

“I do not believe that it is good public policy for state institutions to have major holdings in the tobacco industry,” Richards wrote. “We spend millions of dollars each year in state hospitals and clinics treating the cancers and other respiratory problems associated with smoking.”

A month before the key meeting on June 6, four of the nine regents told The Houston Post they would vote to divest. Another — Regent Sam Barshop — said it was “probably a good idea.”

When the anticipated meeting arrived, the four were true to their word. But Barshop — citing legal interpretations relating to divestiture — cast a “no” vote. Since one regent was absent, it was a tie 4-4 vote and the motion to dump the stock failed. In its place, the regents made all UT system campuses and stadiums smoke-free.

Though Turk said at the time he was “delighted” that the divestment campaign pushed regents to ban smoking, he is now much more critical of the vote. “I’m proud that they went smoke free,” says Turk, now a law student in Houston. “But that move only highlighted their hypocrisy. Now the UT System is the largest smoke-free institution in the world. Yet it is simultaneously one of the largest investors in America’s corporate drug pushers.”

“King of Concealment”

Joel Dunnington, the radiologist at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, also points to the move to substitute the smoking policy for stock divestiture as proof that holding tobacco securities influences university decisions. Without the divestment campaign, he says, UT would not have banned smoking.

“We’ve got to tell institutions to quit investing in tobacco stocks because it influences their decision making,” Dunnington says. “I don’t care what they say.”

Dr. Charles LeMaistre, head of M.D. Anderson, declined to comment on the tobacco stock issue, pointing to his comments at the regents meeting. In an excerpt of the minutes, however, it does not appear that LeMaistre specifically took a position on divestment, though he did say that M.D. Anderson would be one-third smaller if it were not for tobacco-related disease.

Tobacco stocks are not the only way in which M.D. Anderson shares in industry profits. The cancer center has also accepted $235,774 in research funds from the Council for Tobacco Research, a group set up and funded by the tobacco industry.

Michael Courtney, media specialist for the center, calls the CTR “an extremely prestigious council of scientists.” But Richard Daynard, a Northeastern University law professor and editor of the monthly newsletter Tobacco on Trial, says the goal of the industry group is to create doubts that smoking is harmful and cancer-causing.

“The whole purpose of the CTR was to create a pretense for the public that the industry is really confused,” he said. “It was a PR operation.”

In addition, a report by the New York brokerage firm M.J. Whitman points to the CTR as the potential source of a new wave of “conspiracy” litigation charging the tobacco industry with having actively concealed the dangers of smoking from the public. The report advises against investing in tobacco companies, noting that the recent case Haines v. Liggett Group could prove disastrous for the industry. In that suit, Federal District Judge H. Lee Sarokin pointed to the activities of the CTR, concluding that “the tobacco industry may be the king of concealment and disinformation.”

The M.J. Whitman report was released in April, a few days after Philip Morris sent tobacco stock prices plummeting with its announcement that it was cutting the price of Marlboro brands by 40 cents a pack to stem the flow of smokers to cheaper brands.

“We would advise people not to buy the stock of any tobacco companies because the litigation risk is so high,” said Jack Hersch, a researcher with M.J. Whitman. “When it eventually hits home, it could potentially consume the equity value of the company.”

As for the impact of divestment by institutions, Hersch said even relatively large liquidations have only a short-term impact on stock prices. However, if a large number of major institutional investors decided to quit holding the stock, it could potentially have a “major detrimental effect.”

The latest large divestment came in April, just a few days after the price plunge. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan announced it would dump $20.4 million in tobacco and alcohol investments after Detroit newspapers began investigating the holdings. Pressure from tobacco companies failed to stop the divestment. “If someone is going to divest the stock, we’re going to try to let them know why Philip Morris is a good investment,” company spokesman Nick Rolli told the Detroit News.

Jason Wright, a spokesman for R.J. Reynolds parent RJR Nabisco, declined to comment on the divestment issue, saying only that the decision to divest rests with those who hold the stock.

Hospital Hypocrisy

In Houston, the depressed stock prices have energized those fighting for divestment. After the price drop, City Councilwoman Eleanor Tinsley — who spearheaded measures to ban smoking in all public buildings, theaters, and shopping malls — called on the city’s three employee pension funds to dump their $10 million in tobacco holdings. In August, Tinsley reaffirmed her intention to propose a resolution to take city funds out of tobacco.

Another Houston institution that recently announced plans to divest is St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, which holds nearly $ 1 million of tobacco stocks in its pension fund. “St. Luke’s does not condone the use of tobacco and does not have any holdings on its balance sheet,” the hospital announced in a statement. “The employee pension plan contains a small percentage of holdings in tobacco companies. The outside firm which manages these securities has been instructed to divest these holdings as opportunities arise.”

Ron Turk, the Houston activist, initially uncovered the stocks while researching holdings among hospitals last year. He also found that the pension funds of the Memorial Healthcare System, which owns four hospitals in the Houston area, have $2.3 million invested in tobacco stock. Last November, Memorial System promoted the Great American Smokeout — urging consumers to quit smoking the very products the hospital invests in.

Undaunted by bad publicity, the hospital board voted in January to retain the tobacco stock. “It was decided that they would not inhibit the investment counselors in any way,” said spokeswoman Michele Smith. “From what I was told, they did not sell any of it.”

Turk blasted the hospital for its decision, saying the loss of money on the declining stocks was a “severe breach of their fiduciary duty.”

“If there’s any doubt in your mind as to whether hospitals should own tobacco stock,” he said, “go to a smoker’s funeral.”

Tags

Jay Root

Jay Root is a reporter with The Houston Post. (1993)