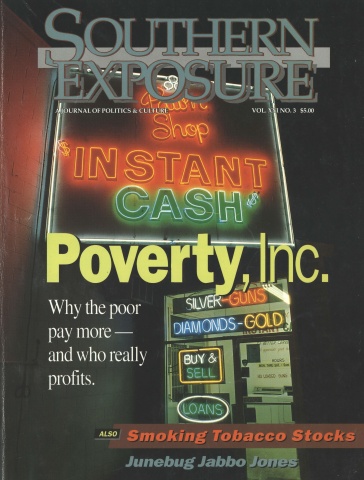

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

DAUFUSKIE, S.C. — The island Yvonne Wilson knew as a child was vastly different from today. Isolated from the mainland and relatively undisturbed by outside influences, the descendants of slaves thrived on the tiny coastal island.

Islanders tilled the soil, hunted small game, fished and shrimped and harvested the oyster beds from the surrounding waters. Everyone took responsibility for raising children. Everything was shared, strengthening the sense of community.

“It was like you lived on Jones Street and you knew everyone on that street,” recalls Wilson. “Here on Daufuskie, the whole island was like a big Jones Street. You knew everyone and everyone knew you.”

“You were raised on Daufuskie to enjoy the simple things in life,” she adds. “It wasn’t like you were better than I was or I had more than you had; we were all basically poor. But it gave us a sense of independence.”

Today, Daufuskie islanders no longer enjoy the simple things in life. Exclusive resorts have spread across the island over the past 15 years, surrounded by imposing walls and guarded by armed sentries. “No Trespassing” signs bar the dirt roads islanders once traveled; hunting grounds and fishing spots are off limits. Pollution has ruined the oyster beds.

“It’s not a truly neighborly feeling on the island anymore,” Wilson says. “Now everyone is competing against each other. It was so different from the way I was raised. We were raised to be as one. But developers have come in and divided us. I hate to see this happening to us.”

The changes on Daufuskie mirror the rapid transformation experienced by dozens of the Sea Islands that hug the coast from north of Charleston to the Florida line. Since Charles Fraser, the son of Georgia timber magnate General Joseph Fraser, launched the first island resort on Hilton Head in the 1950s, air conditioning and new bridges have opened beautiful vistas for thousands of tourists and retirees from the North. Today, few of the islands have eluded development.

The influx of new settlers has placed the eight coastal counties of South Carolina among the fastest growing areas in the Southeast. Berkeley County ranked sixth in the region for population growth during the 1980s, and Dorchester ranked eleventh. The rapid growth has also made tourism the second largest industry in the state, earning an estimated $3.3 billion a year.

By the year 2010, experts predict, an additional 500,000 people will live on the South Carolina coast. Many will occupy the fashionable “plantations” that have sprung up on Daufuskie, Hilton Head, Edisto, Kiawah, and other islands. But while these walled communities offer their mostly white residents the best of coastal living, they threaten to ruin the fragile environment and obliterate the historic way of life for black islanders, once the area’s majority population.

The number of islanders speaking Gullah, a coastal language containing over 4,000 African words, has dramatically declined from more than 100,000 a decade ago. Folk medicine, once a mainstay of the Gullah culture, is rapidly being replaced with modern methods. Midwives, barred from practicing their age-old traditions without state certification, no longer deliver babies along the coast. And the centuries-old African art of sweetgrass basketmaking is in danger of being lost, as the resorts encroach on swamplands and lure younger islanders with jobs.

Islanders say the lack of respect for the “old ways” is epitomized by Melrose Plantation, where developers built a welcome center on top of a graveyard near the sea. The burial spot symbolically linked generations of islanders to their African ancestors.

“Most people in the new culture don’t appreciate the indigenous culture on the Sea Islands,” says Emory Campbell, a native of Hilton Head and executive director of the Penn Center, an organization fighting to preserve Gullah life. “I believe the incoming culture perceives traditional lifestyles as something lesser than their own.”

Table Scraps and Arson

The clash of cultures sometimes involves simple — yet significant — differences in lifestyles. Consider the case of Diogenes Singleton. A lifelong resident of Hilton Head, the 68-year-old islander survives on a small farm that has been in his family for 125 years. Although he has never had a run-in with the law, police came to his home in July and arrested him. His crime? Feeding his pigs food scraps in violation of a state law that prohibits feeding household garbage to pigs sold commercially.

The table scraps cost Singleton six hours in jail and $400 for bond — an expensive reminder that many traditions that islanders have known all their lives are no longer welcome.

Charlie Simmons, another lifelong resident of Hilton Head, also paid the price for his way of life. The 82-year-old islander was fined $238 this summer for refusing to remove old cars, stacks of wood, and other belongings from his yard. Officials say the debris violated an ordinance prohibiting “unsanitary, unsightly, and unsafe conditions.”

The fine surprised Simmons. “I live so far out of town, I don’t see how this could bother anyone,” he said. “The lumber and other stuff has been there for years. It’s never bothered anyone before.”

The day after a local newspaper reported Simmons’ defiant reaction to the fine, his home burned to the ground. Some islanders believe arsonists set the blaze as punishment for his public obstinance.

Other clashes strike at the heart of native culture. Alberta Robinson is one of the few remaining “basket ladies” who sell their hand-crafted wares along Highway 17 in Mount Pleasant, just north of Charleston. Resorts have threatened their livelihood by limiting access to the sweetgrass needed to make the coiled baskets. “We used to walk out through the swamp area in my back yard and get the grass,” says Robinson. “Today we can’t even get to it.”

African slaves brought the art of sweetgrass basketmaking with them to the coast, originally using the baskets to carry the rice they harvested. Their descendants now sell the baskets to survive, often supplementing their meager incomes from low-paying jobs at resort developments.

Although island families have passed the art of basketmaking from generation to generation, many younger islanders brought up in the midst of development are more interested in finding steady employment. Numbering more than 1,200 just a few years ago, the ranks of sweetgrass weavers has dwindled to barely 300 today.

Sweetgrass supplies have declined even faster, says Robinson. What little sweetgrass remains accessible has been depleted — killed by overuse or the runoff from chemicals used to maintain resort golf courses.

“Everyone started using the same grass because it was the only grass we could get to,” says Mary Goggins, another basketmaker. “I haven’t seen any in the area now for over 20 years.” To get the sweetgrass they need, some women travel to nearby Georgia or as far away as Florida.

“It’s ironic,” says Mary Jackson, a basketmaker whose work has appeared in the Smithsonian Institution. “Increased development has brought more potential customers to our region, but it has also wiped out many of the wetlands that we have historically relied on to supply us with sweetgrass.”

Full Up Me Cup

The Gullah language (sometimes called Geechee) found on the Sea Islands developed in an oral tradition from the blending of English and several West African languages. The isolation of the African-American majority on the islands allowed their language to develop a complex structure, with unique and borrowed phrasing, inflections, and accents. E, for example, is the pronoun for he, she, or it, similar to gender-less pronouns in Igbo and other African languages. Tense, voice, and number are also often absent from Gullah verbs. And repetition can indicate degree, as “hungry hungry” to mean “very hungry.”

Here’s how the Wycliffe Bible Translators, working in a team with Sea Islanders, render the 23rd Psalm in Gullah:

De Lawd me shepud!

A hab ebryting wa A need.

E mek me fa res een green fiel

en E lead me ta still wata wa fresh en good fa drink.

E tek me soul en pit em back weh e spos to be.

E da lead me long de right paat,

fa E name sake, same lok E binna promise.

Aaldo A waak tru de walley a de shada a det,

A ent gwine faid no ebul, Lawd,

kase You dey dey longside me.

Ya rod en ya staff protec me.

You don papeah nof bittle fa me,

weh aal me ennyme kin shum.

You gib me haaty wilcom.

You nint me hed wid ail en full up me cup tel e run oba.

Fa true, You gwine lob me en tek cyah a me longes A lib.

En A gwine stay ta ya house fareba.

Storytelling and Sweetgrass

In spite of such devastating encroachment, sea islanders aren’t ready to relinquish Gullah culture to the history books. Nor are they willing to see their communities and natural resources further damaged by the continued influx of new residents. A number of local and regional organizations have initiated programs to preserve and enhance the indigenous way of life:

▼ Residents on at least four different islands hold weekend-long festivals each year to showcase the Sea Island traditions. For example, the Heritage Days Festival on St. Helena Island celebrates its 14th year this November with music, food, crafts, storytelling, and “praise house” services.

▼ Concerned about the ill effects of sprawling development, the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League has begun pointing to traditional island communities as the foundation for self-reliant, sustainable development. The League offers technical assistance on land-use planning, trains native leaders about environmental regulations, and operates a Land Development Project that promotes alternatives to the car-dependent, suburbanization of the islands and neighboring region.

▼ On Daufuskie, Yvonne Wilson and other residents are working to get their homes on the Historic Register as a way to preserve their heritage and attract tourists who will help their economy. Local and national groups in a coalition called Friends of Daufuskie have helped islanders raise money to retain their land and way of life. Funds have already paid for a much-needed ferry, and negotiations are underway to get the county government to maintain the service on a convenient schedule.

▼ Basketmakers have also joined forces to stimulate interest in their art and find new sources of sweetgrass. Coastal weavers pooled their resources to form the Mt. Pleasant Sweetgrass Basketmakers Association. The organizing paid off earlier this year when the owners of Little Saint Simons, a private 10,000-acre island resort off the coast of Georgia that enjoys an abundance of sweetgrass, invited weavers to visit as often as they like to harvest the plant.

The group has also teamed up with the Historic Charleston Foundation and the Clemson Coastal Research and Education Center to sponsor a joint project to cultivate the sweetgrass that once thrived on the coast. The project got a boost from Charleston Mayor Joe Riley, who created a task force in 1991 to study ways of saving the coastal plant. “I knew that our community, our state would not want us to lose this culture,” Riley said.

Recently, more than 100 people turned out to plant 2,000 sweetgrass seedlings at the McLeod Plantation on the Stono River, where slaves once harvested rice, cotton, and indigo. The city of Charleston set aside the area for the project earlier this year.

“For 300 years, the basketmakers have maintained a tradition in the face of incredible obstacles,” says Barry Bergey, assistant director of the Folk Life Programs at the National Endowment for the Arts. “Today they are more than determined to continue. It seems the least the rest of us can do is to pave their way into the 21st century, rather than pave over them.”

Translation and Training

At the heart of the struggle for cultural preservation is the Penn Center. Founded during the Civil War as the nation’s first school for former slaves, the center now works to preserve the Gullah heritage. It operates a museum and archive, conducts educational programs for children, helps islanders retain family land, and works with the local community on environmental issues. At workshops and conferences it hosts, the center regularly includes performances featuring local artisans and storytellers.

“Since developers have come into the islands, we’ve been taught that Gullah is a bad language,” says director Emory Campbell. “But we explain to people here that Gullah is not English. It’s a different language, and they have nothing to be ashamed of.”

Campbell says Beaufort County schools are allowing teachers to visit the center to expose them to Gullah and help them recognize the language. The center is also translating parts of the Bible into Gullah with the Wycliffe Bible Translation Team, a national organization that records unwritten languages worldwide.

Claude Sharpe, a coastal native who is doing the translation for the center, says his interest in the language goes beyond the Bible. “We are also encouraging people to write short stories, novels, and other works in Gullah,” he says. “A lot of problems with illiteracy in the area could be done away with if there was greater respect for the Gullah language here. People learn a lot faster if you teach them in their own language and then translate it into another.”

Perhaps the most ambitious program at Penn Center is the Sea Island Preservation Project, which offers intensive training to island landowners and community leaders. The goal, says project director Nina Morais, is to empower local residents to find ways to balance cultural preservation and environmental protection with responsible development.

“This project will take Penn Center back to its original purpose,” says Morais, an Ohio native and attorney whose love for the Sea Islands lured her away from a successful private practice. “Penn was founded as part of an effort to demonstrate that former slaves could become self-reliant citizens, could control their destiny. It was also an effort to show that there were economic alternatives to slavery. There are strong parallels to what we’re trying to do today.”

Working with the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League and the Neighborhood Legal Assistance Program, the center holds workshops to teach landowners their legal rights and counsel them on tax and inheritance issues — something few older islanders had to worry about before.

The workshops explain how landowners can avoid “partition sales,” a tactic used by developers to take land from long-time residents. A developer buys one heir’s share of a family’s undivided parcel of land, and then gets the court to sell the entire parcel since his share has no fixed boundary. Typically, the outsider can outbid everyone else and walk away with the whole tract of land. Penn Center shows residents how to make out wills and deed transfers to ensure that their land will remain in their families for future generations.

“So many native people have never left wills,” Morais says. “We want to ensure that they have adequate protection against unscrupulous people.”

The center sponsors a 12-day training program for community leaders from surrounding islands and coastal areas. Much of the curriculum focuses on the nuts and bolts of zoning, tax laws, land use, and environmental regulation.

“The goal is to develop teams of leaders throughout the Sea Islands with a sophisticated understanding of key coastal issues,” Morais explains. “We want to especially focus on promoting development that won’t damage the islands’ culture and environment — family-run agriculture, aquaculture, and eco-tourism focusing on African-American culture and history.

“Millions of dollars are made each year from tourism,” she notes. “We want to make sure some of the money flows into and helps preserve the Sea Island communities.”

Developers and Dollars

Despite the potential of the workshops and other organizing efforts, residents know they are in for a long haul. State laws are designed to protect coastal wetlands, endangered animals and plants, and commercial development — everything except people and their heritage. “That’s the flaw in the law,” says Alan Jenkins, an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “Nothing says you have to protect the native culture.”

To make matters worse, island taxpayers are effectively being forced to finance their own cultural demise. More than 50 federal programs support construction along the coast, from road construction and beach restoration to public flood insurance that underwrites building in flood-prone areas considered too risky by private insurers. Taxpayers paid over $1 billion to bail out the nearly bankrupt insurance program in the 1980s.

Worse still, the state agency charged with protecting the coastal region has several developers on its board of directors, and is exempt from state ethics laws prohibiting such conflicts of interest. Wes Jones, the former chair of the agency, was the chief attorney for the exclusive Melrose Plantation on Daufuskie. The private resort also includes Governor Carroll Campbell Jr. among its members.

To Charles Joyner, a former professor at the University of South Carolina and native of the Sea Islands, such close ties mean that no coastal area — and no island traditions — are safe from the onslaught of unrestricted development. “To endure, a community must bequeath its traditional, expressive culture to the next generation,” Joyner says. “Without the living context in which that expressive culture arises, cultural endurance is by no means certain.”

Nina Morais and others at the Penn Center concede that efforts to preserve the heritage of the islands won’t change things overnight. Nevertheless, they are excited about the emerging coalition between blacks and whites, environmentalists and cultural preservationists, and believe it can empower islanders as they struggle to shape their own destiny.

“This effort requires a vision of the coastal region’s future that can gain broader support,” Morais says. “Opposition to resort development is necessary, but not sufficient. Islanders must also learn how to work with those in power and how to imagine an alternative future for their communities that is feasible and persuasive.”

At the same time, environmentalists are learning that saving a culture is critical for saving an ecology. “The two are very interrelated,” says Dana Beach, executive director of the Coastal Conservation League. “For too long, environmentalists have thought in terms of quality standards and ignored the human communities that live with those natural resources, often quite efficiently.”

In 1986, Patricia Jones-Jackson ended her book on Gullah culture, When Roots Die, with a dismal conclusion: “The islanders’ ineffectiveness in resisting the often reckless advances of developers must be laid at the door of the very insularity that for so long protected the culture. Adherence to traditional ways has by and large robbed them of the ability to respond to the intrusion with equal and opposite force.”

Seven years later, there’s a new spirit of building bridges between the old ways and the new, between local leaders and outside allies, between cultural preservationists and environmental conservationists. The success of these delicate alliances may well determine the fate of the Gullah culture.

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.