College Football

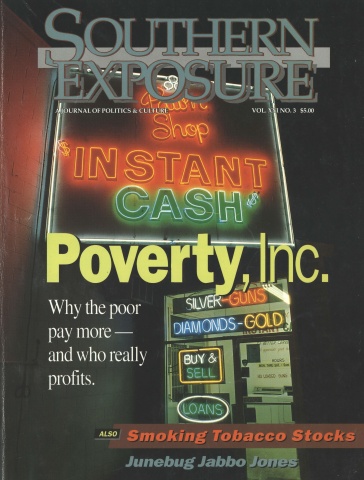

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 3, "Poverty, Inc." Find more from that issue here.

When the Florida Gators and Georgia Bulldogs, two old rivals and perennial national football powers, play each November in Jacksonville, the game is tabbed “The World’s Largest Outdoor Cocktail Party.” Upwards of 80,000 people attend the showdown each year to toast their alma maters and party with friends they may only see five or six Saturdays a year.

The Southern love affair with football dates to before the turn of the century. In 1895 a game played in Richmond between Virginia and North Carolina attracted a crowd of 12,000. Fans were apparently just as rabid then as now — Tar Heel runners were twice tackled by overzealous Virginia spectators who ran onto the field.

Since then, the number of spectators has grown dramatically. By 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Association reported that nearly 19 million fans were watching college football games. Last season, the number hit 36 million.

Five of the 10 states with the highest per capita attendance in the nation are Southern — Virginia, South Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi. The region also boasts the nation’s two best-attended conferences: the Southeastern Conference, with a dozen schools from Tennessee and Arkansas to Louisiana and Florida, and the Atlantic Coast Conference, with nine schools stretching from Maryland through the tobacco belt to Florida.

Part of the sell of college football is that most SEC and ACC schools are located in small towns. The six or seven home football games each season are often the only show in town.

There are occasional fall Saturdays in South Carolina when Clemson University and the University of South Carolina both play home games. Some 80,000 fans attend in Clemson, while another 65,000 view the spectacle in nearby Columbia. On those days, the crowds at the two stadiums rank as the third- and fourth-largest cities in the state.

Perhaps nowhere does college football fever run higher than in Alabama, where former University of Alabama coach Bear Bryant remains the most revered person in the history of the state. When the Crimson Tide claimed the national football championship last season, Sports Illustrated quickly sold out of a special regional edition it printed to commemorate the victory. “

In Birmingham and Tuscaloosa, they have six or seven Saturdays each year when the place to be is where the Tide is playing,” says Bob Goin, athletic director at Florida State. “The same is true here. We’re the only show in town. They’re coming from all over the state to see Florida State football.”

On many college campuses, home games are two-day affairs that last from Friday night until game time Sunday afternoon. At the University of Alabama and Auburn University, students parade around campus on Friday nights, honking their car horns as a prelude to the big event. Fans arrive at the stadium as early as sunrise, unloading lawn chairs and picnic tables in the parking lot and feasting on chicken with all the trimmings.

At Clemson, fans deck themselves out in the school colors. At kickoff, “Death Valley” is a sea of orange, with fans dressed in neon overalls and nearly every face sporting a painted tiger paw.

Such football festivities and traditions have been passed from generation to generation. “There are people buying tickets now whose grandparents bought the same tickets,” says Bob Goin at Florida State. “In our community, we’re the wholesome event. Daddy, Mommy, son, and daughter can save up all year to go to this and have a lot of fun.”

At $18 to $25 per ticket, it can take some families all year to save for a game. College football is not inexpensive, and high prices provide lucrative profits for school athletic departments. At Florida State, where the stadium was recently expanded to seat 70,000 fans, six home football games generate $10 million in revenues. FSU sold nearly 40,000 season tickets this year.

“You can’t get that many people to go vote,” Goin says. “We might be mixed up, I don’t know. It’s a science that I don’t quite understand. All I know is that it’s the socially acceptable thing to do. Rah, rah for the home team, and if they don’t win, it’s a shame.”

Tags

Ron Morris

Ron Morris is executive sports editor of the Tallahassee Democrat. (1993)