Turning Twenty

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 1/2, "Southern Exposure Turns 20." Find more from that issue here.

When I told a long-time friend of Southern Exposure that we were preparing a special issue to celebrate our 20th anniversary, he winced and coughed politely and looked as though I were a dinner guest who had asked for another cup of coffee at midnight.

“Hmmm,” he murmured. “I hope you’re not going to do any of that insidery here’s-how-great-it-is-to-put-out-such-a-wonderful-magazine-and-remember-that-time-we-stayed-up-all-night-putting-out-that-issue kind of stuff,” he said.

Well.

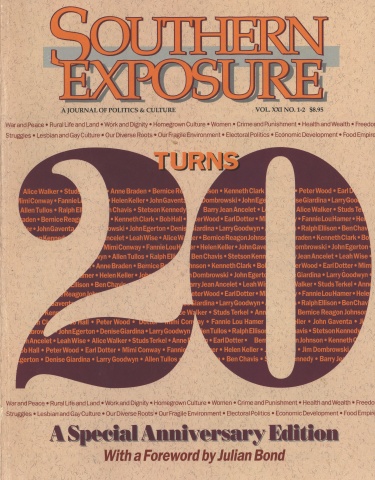

As a matter of fact, we aren’t. But turning 20 does merit a modest bit of self-reflection, especially for a troublemaking and troublesome magazine like Southern Exposure. It is no small feat for such a small publication to hang on for two decades, and we decided to celebrate with this double-length edition of excerpts culled from our first 81 issues.

To better appreciate how remarkable it is that the journal has lasted this long, consider what the editors wrote when the magazine turned one year old in 1974: “This issue of Southern Exposure marks the beginning of our second year of existence, a fact that may come as a surprise even to our most enthusiastic supporters. The odds against a new magazine’s survival are always high; when you consider that we are a ‘regional’ magazine with a supposedly limited audience, the odds become almost prohibitive. Yet we have survived.”

In those early days — with only three issues to its name — survival was always at stake. The magazine was located in small, somewhat seedy offices above Walton Street in downtown Atlanta, the home of its publisher, the Institute for Southern Studies. Julian Bond, Sue Thrasher, and Howard Romaine had founded the Institute in 1970 to serve as a research arm of the civil rights movement, providing strategic information on the changing South.

“Raising money was always hard,” Thrasher remembered, “but feeling confident about the value of our work was always harder.”

The turning point came, according to Thrasher, when staff member Bob Hall decided it was time for the Institute to start a magazine. “In retrospect, I think that without Southern Exposure the Institute would not have been able to remain a viable institution,” she concluded. “The journal helped give us substance, direction, discipline and, most hated of all, deadlines. It also made us reach out for help.”

The result was a magazine that was quite simply unlike anything anyone had ever seen. “People were very surprised that left-leaning Southerners could produce this quality journal,” recalls Bob Hall. “It was viewed as very substantial, and I think people wondered if we could keep it up.”

From the start, SE was more than a magazine. It was an integral part of a diverse, often disjointed movement struggling to bring lasting social and economic change to the region. As such, it was often pulled in many directions at once — by the urgent demands of the day, by the dictates of funders, by the competing ideologies and interests of the staff.

Nevertheless, the magazine was guided by a unifying vision of the South as home — and a shared commitment to defend that home from the growing threat posed by huge corporations. Nearly every serious student of Southern history accepted that race was central in shaping the region, but the Institute staff held that issues of class were also critical to understanding the South.

In the early 1970s, the flow of capital into the region was reshaping deeply ingrained relationships between people, extending corporate control and eroding community values. SE sought to strengthen the positive, sustaining traditions of the region: love of the land, self-reliance, community sharing, indomitable humor, and the continual striving for social harmony in the face of prejudices based on sexual, racial, and economic differences.

In working to build a better South, the magazine relied on two principal tools:

▼ Strategic research. The magazine collected reams of materials to profile entire industries and expose the corruption of corporate power. Issues were often designed as resource books, placing information directly into the hands of union organizers, civil rights activists, community leaders, teachers, and others who could use it to demand change and create alternatives. When need demanded, the Institute and the journal sometimes helped create new grassroots groups, including the Carolina Brown Lung Association, Southerners for Economic Justice, the Gulf Coast Tenants Leadership Development Project, and the National Contract Poultry Growers Association.

▼ Popular history. The creation of the magazine coincided with the revival of oral history, and SE nurtured a pioneering cadre of young historians pushing to empower ordinary Southerners to speak for themselves. The journal documented the history of little-known but intense battles with corrupt powers in the region, demonstrating both the power of organized resistance and the positive values within Southern culture that supported it. For the magazine and the Institute, such history suggested important lessons for contemporary grassroots campaigns.

Ordinary Southerners telling their own stories? Journalists joining the struggle? Here was a journal practicing a new kind of journalism. At best, the mainstream press assumed that it was enough to single out individual wrongdoers, inform a literate and middle-class public about injustices, and wait for readers to call their congressmen. Southern Exposure knew that to bring about meaningful change, we must understand the systematic nature of our economic system — and organize people to take action.

For SE, journalism and activism have always been inseparable. We write about the region because we wish to understand it and, ultimately, to change it for the better. We document and participate in social change movements that help all of us as Southerners gain greater control over our lives.

This unique mission has often made the magazine hard to classify. Is it a book or a magazine? Should we publish our own research or serve as a forum for others? Should we publish pages of charts and numbers for the truly committed, or condense our findings for the seriously overcommitted?

Such issues inevitably arose while we were preparing this anniversary edition. We decided to heed our nervous friend and highlight our work instead of our memories. To that end, we have excerpted articles that represent a variety of styles and approaches and grouped them according to a few of the broad subjects that SE has tackled over the past two decades.

Far too much has been left out, however, to consider this a “best of” collection. There is nothing here from the dense and detailed “Tower of Babel” issue that served as a vital workbook for anti-nuclear activists in 1979, nothing from the 1984 issue on Southern history entitled “Liberating Our Past,” nothing on religion or our investigations of high finance or the syndicated column “Facing South” we started in 1976.

Because we have grouped excerpts by topic, this edition also tends to obscure the imaginative and fluid nature of the journal. SE has always crossed traditional boundaries, advocating the connections between jobs and justice, rural life and economic development, race and the environment, women and health.

Nevertheless, such limitations cannot obscure the diversity and importance of the work included here. In a sense, this issue offers an incomplete but engaging introduction to the history of the Institute and the magazine — a glimpse of where we’ve been, what we’ve seen, and how we felt about it at the time.

This issue also underscores the importance of the collective effort behind Southern Exposure. The magazine has never been the sum total of any one person. Thousands have contributed their talent and imagination to it over the years, and the journal is the product of their dynamic and multifarious interactions.

Still, no anniversary celebration would be complete without a nod to two people whose extraordinary creativity and commitment continue to nurture and sustain the magazine. Bob Hall, whose vision set the journal in motion 20 years ago, still contributes to the magazine as research director of the Institute. Jacob Roquet, who has designed every issue of the journal since 1982, celebrates his 50th effort with this edition.

We remain connected to our past as we plan for our future. The Institute has created an endowment called the Investigative Action Fund to support our brand of in-depth journalism, create internships, and train grassroots leaders. We also have several projects in the works to strengthen the capacity of grassroots communities to develop their own economic enterprises.

Like the South itself, we will continue to grow and change. From one window of our office we can see the smoke from the kiln of a local pottery shop and a small, green miracle of woods. From another window we are confronted by a liquor store, a laundromat, and one of those prefabricated strip shopping centers that have malled so much of the region.

Between such contrasts there is still much to discover about the South. As the editors wrote on our first anniversary in 1974: “We look forward to this year as a further opportunity to provide needed insights and analysis into Southern culture, politics, and economics. We think you’ll agree that the wealth of material and the need for enjoyable reading and fresh perspectives can easily keep the journal going for some time.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.