Shining Light

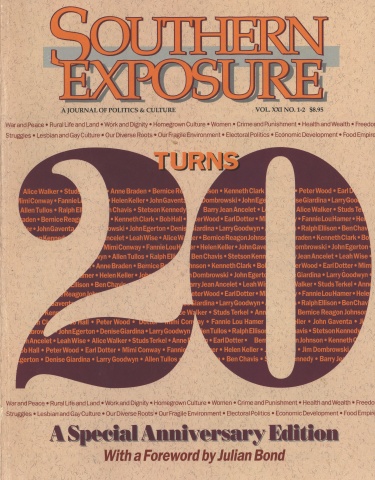

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 1/2, "Southern Exposure Turns 20." Find more from that issue here.

Lyndon Johnson died in retirement and Spiro Agnew resigned in disgrace the year Southern Exposure first saw the light.

Johnson’s presidency had marked the climax of the modem civil rights movement; Agnew’s tenure cemented the racialization of national politics.

In the two decades since 1973 much of the idealism and hope that characterized the movement which produced the magazine seems to have withered away.

The young college students I teach today at a large public Southern university read each day’s frightful headlines and tell me that things have never been as bad as they are now. I tell them, looking at life from a longer perspective, that things are much better now than when I was their age.

The 20 years — from 1953 to 1973 — that preceded Southern Exposure were years of great progress. For nearly all that time a nonviolent, black-led but interracial mass movement challenged white supremacy.

It wrote new laws, helped set loose a black political movement, and eliminated legal apartheid from the American South. It built a democratic movement on the theory that ordinary women and men can speak and act for themselves and that they can challenge power and wealth and win. It celebrated the culture of ordinary people.

Southern Exposure has continued and expanded the work that movement began, and if the assessment of the period from 1973 to 1993 isn’t as positive as the two previous decades, it isn’t because the writers and editors of this magazine haven’t tried, and like the earlier movement, won some victories too.

They have used the techniques of investigative journalism and economic analysis, tracing how money corrupts a community’s values as surely as it corrupts its politicians.

The magazine has used its pages to expose greed and to show how some communities fought back.

It also used them to let a larger audience learn about the beauty and the quirks of the Southern region and its people that aren’t written about elsewhere.

Southern Exposure has filled a void that other publications — and other institutions — have helped create. By emphasizing economic analysis and by letting people speak in their own words, they’ve begun to influence how others see and write about the South’s present and past.

It is only recently that civil rights historiography in universities has begun to focus on community struggles rather than on charismatic leaders, and that historians have looked beyond official records to record the voices of the history makers. More and more scholars realize that yesterday’s movement wasn’t won just by the heroic figures of Kennedys and Kings standing alone; behind them we now see an army of women and men, doing the difficult and often dirty work that preceded the triumphal march.

Southern Exposure can take credit for shining its light on formerly obscured movements against poisonous waste and poisoned food, on industrial plants that cripple workers’ paychecks, lungs, and limbs, on defense spending that militarized the region’s politics, and campaign spending that bought and sold the region’s elected officials. Its readers learned about quilters and chicken pluckers, about coming out and growing up Southern, about bawdy belles and converted Klansmen.

Many of these stories had escaped the national spotlight for the last 20 years. Much of the research broke new ground. The magazine tied campaign contributions to highway development. It gave voice to the voiceless, demonstrating that the ungrammatical aren’t always inarticulate, and that the seemingly powerless possess great strengths.

Another Southerner sits in the White House today. Southern Exposure detailed his environmental record during the 1992 primaries and gave mainstream journalists a “green index” measuring rod to compare clean-up claims, state by state.

A New South Governor is President, at least in part because this magazine pulled the region closer to the rest of America, while helping it to preserve its best and to resist America’s worst. It has been a guidebook, reference library, preserver of hidden cultures, and an entertaining read.

It has shown its audience a South truly neither old nor new; struggling to come to grips with its past, fearful of discarding the worthwhile with the wicked, still hopeful about a tomorrow in which it can teach the nation how to prevail.

Tags

Julian Bond

Julian Bond was a founder of the Institute for Southern Studies and served as its president for several years. He was the communications director of SNCC, served in the Georgia state legislature, and was a professor at the University of Virginia.