This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 4, "Fast Forward." Find more from that issue here.

Ever since D.W. Griffith released his cinematic masterpiece Birth of a Nation in 1915, most films depicting the South have projected a one-sided image of white and black Southerners. From Gone With the Wind to Glory, Hollywood studios have portrayed race relations in the region as a static exchange in which the villains and victims are black, and the saviors are white.

The film imagery has its roots in slavery. Most of the earliest plantation melodramas presented black women as maidservants to their white mistresses, meek victims of their rapacious white masters, and complacent breeders of another generation of enslaved black children. Black men were cast as manipulative, sexually violent, and selfish — as rapacious as their white male counterparts when left to their own devices, yet as meek as their black sisters in the presence of white men.

In Birth of a Nation, Griffith simply consolidated these already existing stereotypes of the black community. The film portrays the black man as the epitome of criminality. A black matriarch — played by a white woman in black-face — tries to protect a white Southern belle from the lustful advances of an educated mulatto politician and an unruly black field hand. When the matriarch fails to domesticate the black brutes, the Klan rides to the rescue. The film garnered the praise of President Woodrow Wilson and provided the Klan with a recruitment tool to enlist members in the North.

Although the stereotypes in Birth date from plantation days, such images remain all too prevalent today. In real-life politics as well as make-believe movies, the black community is still portrayed as prone to sexual violence (consider the threat of rapist Willie Horton used by George Bush during the 1988 campaign) — and as best subdued by state force (consider the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police last year).

In recent years, film studios have churned out a series of nostalgic melodramas about civil rights. Unfortunately, these movies do little to reverse the stereotypes of earlier motion pictures. In most cases, the films show racial injustice as a solely Southern phenomenon. In Mississippi Burning (1988) and Glory (1988), Northern white men rescue blacks from the bigotry and violence of Southern whites. In Driving Miss Daisy (1989) and A Long Walk Home (1991), Southern white women overcome their prejudice and come to see their black servants as friends. The accusatory finger never points to segregation in the North; the popular media condition audiences to accept racism and its murderous history as part of the rural Southern landscape.

Independent films like Harlan County U.S.A. (1976) and Matewan (1987) offer exceptions to this rule, depicting a landscape in which working-class whites join forces with blacks and women against their powerful employers. In the past year, however, three new films — including two produced by Hollywood studios — suggest that this alternative vision of Southern race relations is gradually finding its way into the mainstream media.

All three films — Daughters of the Dust, Mississippi Masala, and Fried Green Tomatoes — resist black and white stereotypes of the Southern melodrama, promoting a broader awareness of civil rights that encompasses women and gays. Two of the films focus on the bonds between Southern women; the third dramatizes hatred and bigotry between two different colored communities. Taken together, these films move beyond the static images of earlier movies to present a dynamic portrait of black, white, and brown Southerners.

Race and Utopia

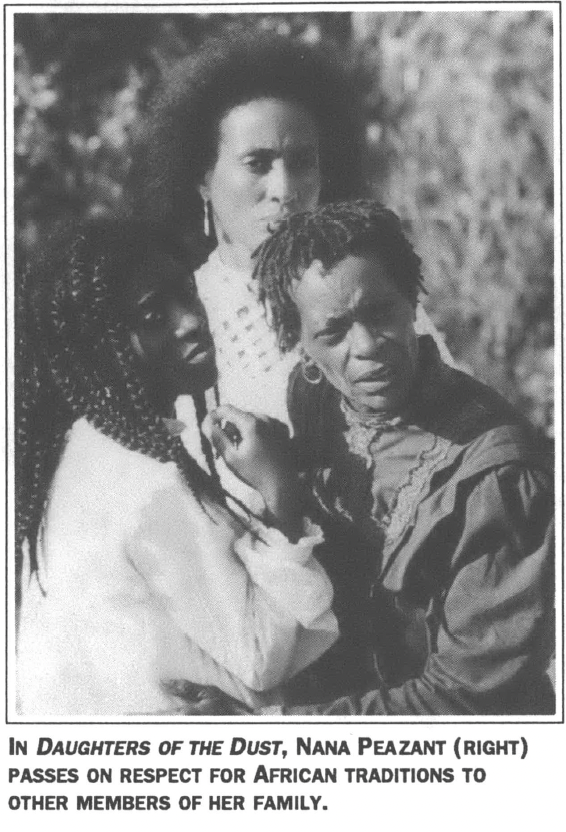

Ibo Landing, one of a hundred sea islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, is the setting of Daughters of the Dust. The year is 1902. The Peazants, an extended African-American family of Gullah people descended from West African slaves, are preparing to leave their ancestral home. Their imminent departure worries Nana, the 88-year-old matriarch who guards the Yoruba religious rituals and cures she learned from her West African elders.

Nana refuses to accompany the family to the North, fearing the move would break her connection with her African ancestors who lie buried on Ibo Landing. She knows that her knowledge of the family’s oral history, her skillful use of the island fauna for medicinal purposes, and her wisdom and daily rituals cannot be transplanted. She is a root doctor and spiritual leader who rejects the temptation of modernism and a better life on the mainland.

Other members of the family consider Nana primitive and superstitious. Her most vocal critics, Viola and Haagar Peazant, embrace Christianity and argue for Northern migration, saying it will improve their lives.

Ignoring their criticism, Nana seeks help from the spirits of her ancestors. She converses with her deceased elders, asking them to guide the departing family members on their migration to the North. Throughout the film, the dead are given life through her voice-overs, which director Julie Dash uses to languidly guide the camera through the lush green vegetation of Ibo Landing and the lives of its yellow, brown, and blue-black inhabitants. By the end of the film, Nana has managed to instill in each family member a reverence for their Yoruba past.

Like the Peazants in Daughters, members of the East Indian community in Mississippi Masala experience culture shock when they are uprooted from their ancestral land and seek refuge in mainstream America. Expelled from Uganda by the dictatorship of Idi Amin, the family migrates to Greenwood, Mississippi. Ethnic rivalry soon erupts with their African-American neighbors in a community dominated by white townsfolk.

At first, director Mina Nair shows residents of different colors coexisting in peace. “Black, brown, yellow, Mexican, Puerto Rican — all the same,” declares an East Indian character. “As long as you’re not white, means you are colored. Honest people of color must stick together.”

A split occurs, however, when Demetrius, the black owner of a carpet cleaning business, falls in love with Mina, the daughter of an East Indian motel operator. The interracial relationship brings underlying racial tensions to the surface. The East Indian community wants Mina to abide by their customs, which permit her father to arrange her marriage. “People stick to their own kind,” her father tells her. “You’re forced to accept that when you’re older.” Similarly, the African-American community wants Demetrius to be mindful of the unwritten law against interracial intimacy. “What’s wrong with you, boy?” says his father. “Don’t you know the rules?” Although the East Indians boycott Demetrius and white bankers foreclose on his business loan, the young lovers ignore the racial hatred of their elders and elope.

Two young lovers also buck the status quo in Fried Green Tomatoes — except in this case the lovers are lesbians. At the Whistle Stop Cafe, Idgie and Ruth work alongside the black male cook Big George and his mother Sipsey to feed an Alabama town of black and white Southerners. Unlike the contemporary reality of Masala, the cafe is a Depression-era utopia where race and sexuality seem to evade the clutches of Southern determinism.

As in Masala, though, there are divisive forces at work. Idgie and Ruth are oddities in their rural Southern community, and some Whistle Stop residents do not condone their activities. Sheriff Grady and the local Ku Klux Klan chapter want the two white women to stop being so chummy with their African-American staff and patrons, but Idgie and her extended interracial family simply shrug off the warnings.

“It don’t make no sense,” says Sipsey. “Big old ox like Grady won’t sit next to a colored child when he eat an egg shoot right out of a chicken’s ass.”

When Klansmen from Georgia arrive to intimidate the black staff, however, the sheriff sides with the women and prevents the hooded intruders from whipping Big George. Throughout the film, director John Avnet portrays a South in which racism and homophobia are nearly absent until the Klan enters the frame.

Joining the Struggle

All three films reject the Klan mentality of Birth of a Nation and its descendants, offering an enduring critique of racism. Even Daughters, with its absence of racism and inter-ethnic rivalry among the Peazants, makes clear the racism of the world beyond Ibo Landing. One character, Eli, maintains an interest in the anti-lynching movement of the early 1900s, and director Dash underlines its importance by ending the film with Eli’s departure to join the struggle on the mainland.

Despite their awareness of the forces of hatred, all three films stress the strength of the central characters. Never do we see racism destroy the spirituality of the Peazant women, the love between Demetrius and Mina, or the interracial and lesbian camaraderie which enlivens the Whistle Stop Cafe.

In this way, each film fosters a feminist understanding of civil rights. All three develop interesting portraits of their female protagonists, and the two directed by women allow female characters to tell the story. An elderly Idgie narrates Tomatoes, and the narration in Daughters alternates between an elderly Nana Peazant and a girl-child who is soon to be born.

Just as contemporary civil rights legislation provides us with remedies for discrimination based on race, gender, and sexual orientation, these three films provide us with alternative views of racism, sexism, and homophobia. The community depicted in each film represents the uneasiness of a society faced with emerging coalitions fighting the privileges of the status quo.

All three films resist beliefs, socio-cultural customs, and detrimental ideas and practices which would inhibit the growth of their central characters. Nana Peazant struggles against the modernism and Christian fundamentalism that threatens her African traditions. Mina and Demetrius fight the prejudice that censures people of brown, black, yellow, and red complexions from loving those outside their racial and ethnic communities. Idgie and Ruth confront the racism and homophobia cloaked in Christianity that censure their love for each other and their friendship with black people.

At the end of Fried Green Tomatoes, after Ruth dies and Idgie moves on, Whistle Stop becomes a ghost town by the side of the tracks. “When that cafe closed, the heart of the town just stopped beating,” Idgie concludes. “It’s funny how a little place like this brought so many people together.” L

ike the Whistle Stop Cafe, the three films provide psychological escapes from small-town mendacity. Like Nana Peazant, Idgie and Ruth, and Mina and Demetrius, they create spiritual and loving places for a new generation of moviegoers.

Tags

Mark A. Reid

Mark A. Reid teaches African-American literature and film at the University of Florida-Gainesville. His Redefining Black Film will be published by the University of California Press. (1992)