This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 4, "Fast Forward." Find more from that issue here.

The Lost Colony Film is available through the State Film Library at all public libraries in North Carolina. Tom Whiteside is assistant director of film and video at Duke University and editor of the upcoming media arts newsletter Workprint. For more information contact Box 90671, Duke University, Durham, NC 27706.

Many years ago I was a guest at a Nags Head beach cottage, one of the lovely old family homes of the “unpainted aristocracy” poised on the easternmost edge of the continent. The house was filled with a poignant sense of history, and two pictures in the living room caught my eye. One was a large, colorful map showing the chief industrial and agricultural products of the United States by region. Published in 1953, the map boasted more than 100 symbols — an oil derrick in Texas, a wedge of cheese in Wisconsin, a fish and a tobacco leaf in North Carolina.

Way out West, next to Los Angeles, was a reel of motion picture film. The little symbol, I realized, represented nothing less than the cornerstone of the modem entertainment industry. As predictable as cars coming out of Detroit, movies came out of Hollywood.

The other picture that captured my attention was a grainy black-and-white photograph, a production still from a 1921 movie known as The Lost Colony Film. It showed folks from the nearby community of Manteo dressed in rather elaborate colonial costumes acting out the settlement and mysterious disappearance of the first English colony on Roanoke Island.

That film, however, was not made by Hollywood. It was made by the people of Manteo, Edenton, Elizabeth City, Hertford, and other neighboring communities. Lacking the powerful machinery of the emerging film industry, local citizens banded together, using the power of their community to tell their own story.

In 1921, Hollywood was barely 10 years old. Commercial radio broadcasts were brand new. Television, the invention that has dominated the second half of the century, was only a far-fetched idea. Yet in an isolated corner of North Carolina, a group of civic-minded enthusiasts undertook a film project that could be considered the beginning of independent media activism in the state.

Miss Mabel

Roanoke Island was a remote place in 1921. A few hardy folks vacationed in Manteo and Nags Head, but it was quite different from the condominiums and cottages that line the beach today. It was a rugged place. There were no bridges to the Outer Banks. The Wright Brothers had first flown at nearby Kitty Hawk just 18 years before.

The island had been among the first settled by the English, but the history of its two failed colonies had been overshadowed by the success of settlements in Jamestown and New England. The people of Manteo felt their heritage deserved to be more widely known. As early as 1880, civic pride had led them to organize programs in recognition of Fort Raleigh and its inhabitants, the colony that disappeared without a trace in 1590.

To popularize the story and gain a wider audience, a group of residents decided to use the new medium of film to tell their tale. No one contributed more to the effort than Mabel Evans, the superintendent of schools for Dare County. “Miss Mabel” scripted the film and traveled to Raleigh to secure $3,000 in funding from the State Board of Education and the State Historical Commission. Bureaucrats were keen to use motion pictures as an educational tool, but they felt it might be more prudent to make the first film closer to Raleigh. Evans persisted, and the movie was shot “on location” in Manteo.

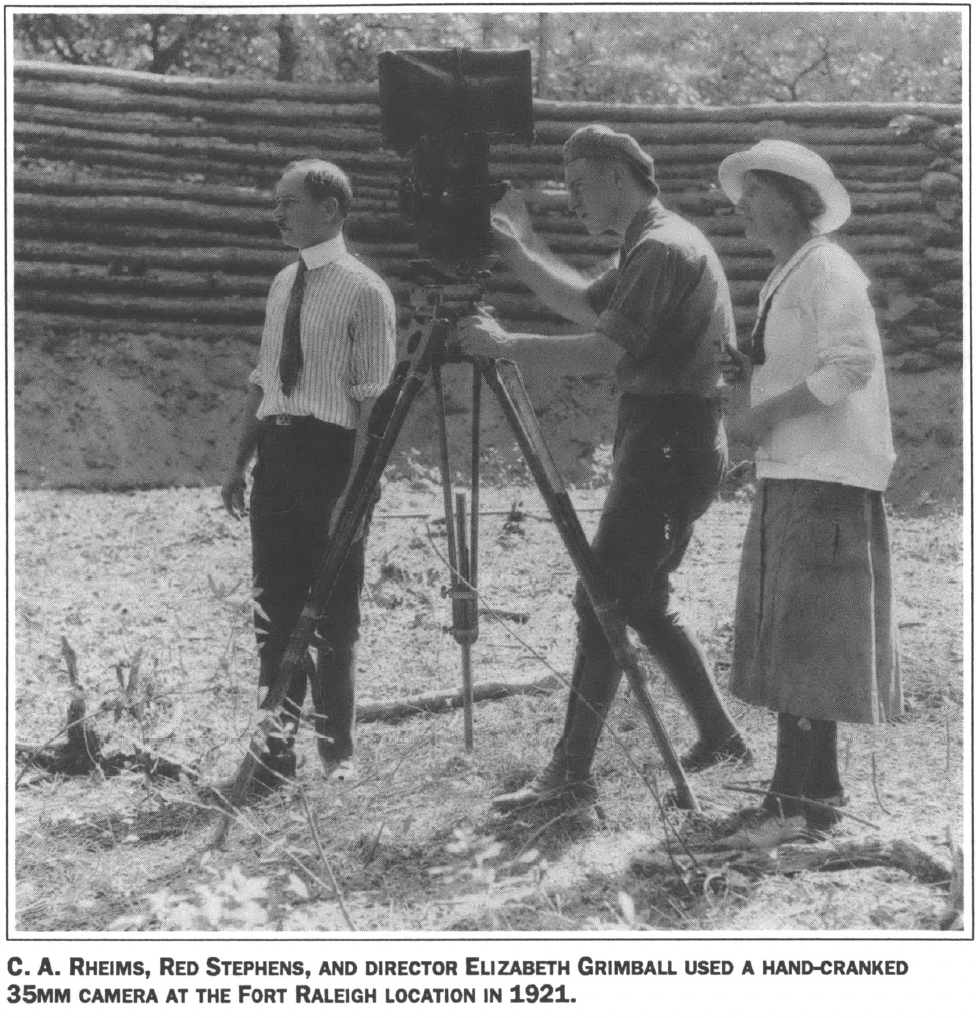

Shooting started in September. The film had a professional crew of three — cameramen C. A. Rheims and Red Stephens of the Atlas Educational Film Corporation of Chicago, and director Elizabeth Grimball of the New York School of Theater. Mabel Evans organized a volunteer cast and crew of 200, and she herself played the part of Eleanor Dare.

When the film was in production, business in Manteo came to a standstill. Everyone worked on the movie. Rope was unraveled and dyed for Indian wigs. Men and boys made bows and arrows, women and girls made costumes. Oscar Daniels of Wanchese turned a shad boat into a 16th century galleon by constructing a canvas-covered frame that fit over the deck. The boat appears in an extraordinary 70-second shot in the film, sailing from right to left in the far distance. As not much more than a large dot on the horizon, the ship is convincing enough, and the long length of the shot helps convey the 67-day voyage of uncharted seas that brought the first explorers to Roanoke Island in 1584.

Although little archaeological exploration had been done by 1921, the islanders knew the exact location of the original Fort Raleigh. They went there to film, and built a set on the site. More than two decades later, when the site was fully excavated, archaeologists discovered that a trench dug by the film crew crossed an actual wall of the original fort.

Many of the volunteers who worked on the movie had never seen a motion picture before, so organizers set up a projector and showed films to give everyone a sense of the project. All of the actors were amateurs. Though some had extensive experience on stage and in pageants, none had been on camera before. There is more posing than acting, although Dr. W. C. Horton brings a high degree of histrionic gusto to the role of John White, governor of the colony and the one who discovered it “lost” in 1590. Horton, a dentist from Raleigh, emotes, gesticulates, and anguishes in fine fashion. What we fail to see him do, however, is paint.

Much of what we know of the original coastal inhabitants who greeted the first English explorers we know from the watercolors of John White. Engraved by Theodore de Bry and published in 1590, the images introduced Europe to this land and what grew here — not only tobacco and sassafras, but also the people and their culture. Today their language is unknown, their culture destroyed by contact with the whites. But from White’s pictures we know something of their dress, their dances, the way they built their houses and canoes, laid out their towns, fished and farmed. It would be difficult to imagine the life of the coastal Indians were it not for the records made by one of their visitors.

These images are retranslated in the movie. In the second reel, Captain Barlowe and seven men visit the village of Chief Granganimeo. In one of the film’s most satisfying sequences, we see the stockade enclosure of the village, some buildings, and various activities such as grinding corn and broiling fish. All of these images come directly from White.

Media Power

After post-production work was completed in Chicago, the film premiered on November 7, 1921 in the Supreme Court chambers in Raleigh before an audience of 150 state officials and friends. State Superintendent of Public Instruction Dr. E. C. Brooks was master of ceremonies and Governor Cameron Morrison was in attendance. Although the five-reel film suffered under the unwieldy title The Earliest English Expedition and Attempted Settlements in Territory Now the United States 1584-1591, it received a hearty stamp of approval and was soon being distributed throughout the state to community clubs, colleges, and public schools.

The film toured the state for five years under the auspices of the Bureau of Community Service, a state office established “to improve the social and educational conditions of rural communities through a series of entertainments consisting of moving pictures selected for their entertaining and educational value.” The bureau provided a projector and screen for showings, as well as a generator to supply power to locations that had no electricity.

The Lost Colony Film was intended to be the first in a series of state-funded films entitled “North Carolina Pictorial History.” No other films were produced — a fact that attests more to the remarkable achievement of Miss Mable and her Manteo neighbors than to the lack of other deserving subjects.

After the film was completed, in fact, many members of the original cast continued to give live performances and pageants, always “on location” in Manteo. The grassroots effort led to the premiere of the “symphonic outdoor drama” The Lost Colony in 1937, a play which still runs each summer. The play has been seen by more than two million people, spawning the entire genre of outdoor drama.

But the film did more than inspire mosquito-slapping theater for tourists. Seventy-one years after it was produced, The Lost Colony still shines as an example of media arts activism in its pioneering use of the film medium for a purpose other than financial gain. Remarkably forward-thinking for its time, this early media effort can serve as inspiration to independents today. If the residents of Manteo and neighboring communities could overcome the challenges of their day and succeed in telling their story, then modem-day media activists should be able to do no less. From raising funds to rounding up volunteers, the work seems much the same as it was 71 years ago.

The film also serves as a reminder of the importance of placing media power in the hands of ordinary people. To maintain a sense of identity, of community, of place, we must periodically reexamine our artifacts, our images, our memorials. This cannot be left to Hollywood, or Raleigh, or Washington. It must be done “on location,” by those who know where the old things are and what they mean. It must be done in the language of the day.

Tags

Tom Whiteside

The Lost Colony Film is available through the State Film Library at all public libraries in North Carolina. Tom Whiteside is assistant director of film and video at Duke University and editor of the upcoming media arts newsletter Workprint. (1992)