This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 4, "Fast Forward." Find more from that issue here.

PUBLIC ACCESS

Durham, N.C.

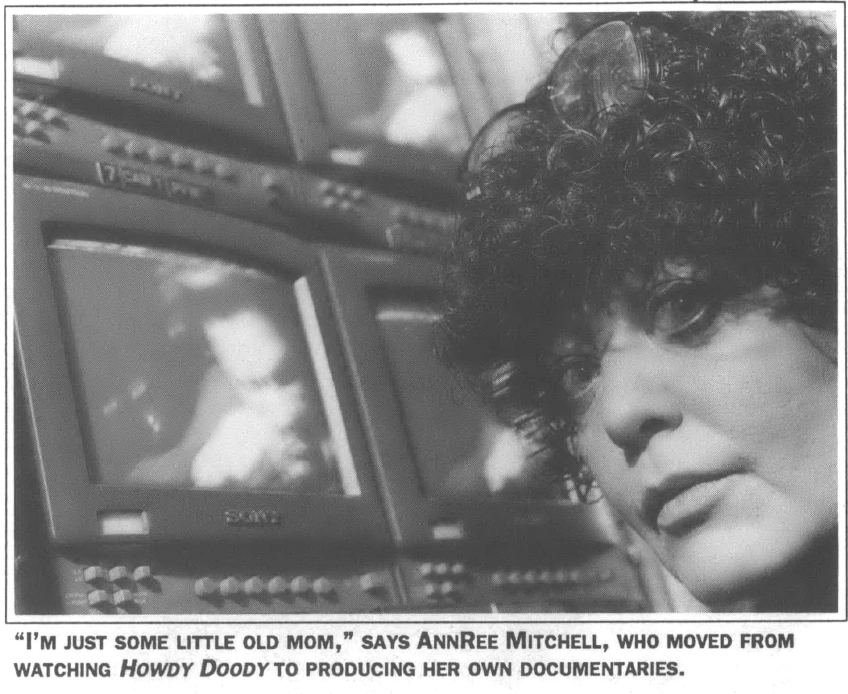

When AnnRee Mitchell was growing up in North Carolina, her favorite television shows included Howdy Doody and the musical antics of Liberace. But when she got behind a camera herself, the Carrboro artist began producing very different kinds of programs — documentaries about the environment and community health.

Her series of shows entitled North Carolina 1990 and Beyond covered environmental issues ranging from right-to-know laws to recycling. Her documentary Waste Wars about a controversial waste incinerator in Caldwell County brought threats to her safety. And her insightful look at local organizing in A Yard Meeting in Granville County made the program a source of information for corporate and state government officials alike.

“When you put it on the TV set and people are watching and going through with their remote control, it’s a great equalizer,” says Mitchell. “I’m right up there next to NBC and HBO, and viewers don’t realize I’m just some little old mom in Carrboro.”

A few miles down the road in Durham, David Merritt made a similar transition from watching mainstream TV to producing alternative programs. After he graduated from East Carolina University in 1990, Merritt went to work to broaden the role of minorities in the media.

“It’s important that our people tell our own story, so there’s no misrepresentation,” he says. “History has shown that control of the media is very important in society. For African Americans to be represented in a respectable and honorable way, we must master that medium so we can control our representation to the masses.”

Mitchell and Merritt share much in common. Both are African-American artists who turned to video for its potential to reach a broader audience. Both are committed to making a social statement with their documentaries. And both have found a forum for their work on the local public-access channel on cable television.

Public access first emerged during the late 1960s, when cable companies were required to provide local residents with free production facilities, train them in their use, and reserve at least one channel for the programs they produced. The result was an atmosphere of greater participation and empowerment that transformed viewers into producers. For the first time, the public had access to the airwaves that was unavailable on commercial networks or public television.

Mitchell and Merritt both produce shows on the public-access channel provided by Cablevision. As in most parts of the country, residents must attend a month-long series of training sessions before they can use production facilities. Participants learn how to operate equipment and become familiar with the jobs of studio personnel. Trainees must then volunteer for five hours in the studio, attend a location shoot supervised by a producer, and complete seven additional hours of advanced training in graphics, audio production, and editing.

Those who survive this media boot camp receive the equipment and studio time they need to develop their own projects — access that makes the expensive world of television production available and affordable to the entire community.

“I meet people who have a very weird perception of what I do, and hardly ever is it accurate,” says AnnRee Mitchell. “The general perception of producer is someone with money — but I do documentaries because it’s the only thing you can do with a small budget.”

“Regular People”

Mitchell was one of the first residents to take advantage of public access on Cablevision. During the late 1970s, she was working as a caterer to support herself as a painter when she met Corey Allen, who had directed episodes of Star Trek and Hill Street Blues. Allen expanded her vision of the potential of video and critiqued her work. Since then, many a station manager has come and gone at Cablevision, but Mitchell remains.

Mitchell says her background as an artist has influenced her television work. “Because I’m a painter, it really does affect the way I look through the camera. Look at this toy box, this paint box! That’s light and sound and motion — and they call it TV!”

Mitchell sets high standards for her work. “There are some days I’m very proud of us,” she says, “and other days I want to crawl under a rock.” But being judged on the same technical level as commercial television has made it difficult for public-access producers like Mitchell to air their programs on the Public Broadcasting System.

Mitchell is quick to point out, however, that the major networks are growing accustomed to using real-life footage shot on home video cameras — such as the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers. “Don’t look down your nose at my public access camera ever again,” she says.

Such high standards have brought results. Officials at the Federal Communications Commission recently called Mitchell a “visionary,” and she is the first producer in North Carolina to air her work over Deep Dish, a national network which broadcasts local public-access programs throughout the country. She is also the first producer to simulcast one of her productions over public-access stations in Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill.

“The fact that public access is not censored is its greatest asset — besides being free of charge,” she says. “It allows us to bring important issues to the community in a healing, open, honest way.”

In addition to her work on environmental issues, Mitchell has produced music videos featuring local jazz, rock, and gospel artists. She is especially proud of her work with an alternative rock band called Rat Duo Jets. “It’s not easy working with rockers if you’re a woman,” she chuckles.

Although she has spent over a decade in public access, Mitchell still marvels at the forum it provides. “If you think about what we’re doing, it’s amazing. A bunch of regular people — non-TV-trained, regular day-job kind of people — come together and often do live TV. People get all worked up over Saturday Night Live, but we do it all the time.”

Inner-City TV

David Merritt, like AnnRee Mitchell, views television as an outlet for his talents as an artist. “Media for me means art, all artistic mediums,” says Mitchell, who can trace his interest in drawing back to the age of two. Through his sketches, he has been a storyteller.

“I used to make long storyboards of complicated fight scenes and things of that nature. So, I guess I’ve always been able to create things in my mind. When it came to doing videos and film, that was a great asset.”

Merritt produced his first video as a sophomore majoring in art history at Eastern Carolina University, and he was struck by the creative potential of the medium. “There was something very immediate about video. It was very economical, and at the same time you could make a social statement.”

Merritt first heard about public access from a friend. “As an opportunity, it was great. It was almost unbelievable that you could use all this equipment for free.” He completed the initial training at Cablevision, and was soon helping others with their productions.

He also began producing documentaries of his own. The Legacy, which traces the history of African Americans through slavery and bondage, was broadcast nationwide over the Deep Dish network. “I wanted to make people think,” Merritt says. “People do not have a sufficient knowledge of the true heritage of African Americans. All scientists know that life started in Africa. We are the kings and queens of humanity.”

Last March, Merritt and Chuck Davis of the African Dance Ensemble traveled to West Africa to record the performance and to document the meaning of traditional African dances. The project, entitled The Definition of Dance, was filmed on location in Gambia and Senegal. When he returned to Durham, Merritt used the public-access facilities to edit his footage.

“This is a very important piece,” he says. “If it is done correctly, we will have an opportunity not only to go back to Gambia, but up and down the West Coast of Africa.”

Merritt has also used public access to reach out to inner-city youth. He has taught video classes in local housing projects and produced a show called FGP 3 — Fellows Gettin’ Paid the Right Way — to dispel myths about disadvantaged kids.

“There’s a big stereotype out there that puts them in the category of criminal,” Merritt says. “They just get into trouble like any other kids. The video shows these kids in their own environment, not gang banging, but being productive. They are learning how to get paid the right way through jobs and opportunities.”

Such shows demonstrate how public access can provide a media forum for those with a message. “I want people whose voice is seldom heard to use public access,” says Merritt. “There’s a lot of the majority already on network TV, so we need lot a more of the minority — different ethnic groups, different persuasions all together. Simply get your voice out there and let your story be heard. That’s what it’s all about.”

— Kathrandra Smith

APPALSHOP

Whitesburg, ky.

This is how the documentary Fast Food Women begins: It is dark outside, but lights are on at the Druthers fast food restaurant. The camera closes in on the kitchen, where the people inside are scurrying to prepare breakfast.

As the sun rises, Sereda Collier fills Styrofoam plates with bacon, scrambled eggs, biscuits, gravy. She is slightly built, with gray hair and a wrinkled face. She stops for a second, lifts up the comers of her apron and briefly fans herself with it. “Whew. It’s hot.”

Collier took a job at Druthers seven years ago after her husband, a coal miner for 17 years, was laid off and couldn’t find work. She didn’t want to talk about her low pay and lack of benefits.

“I’m real tired,” she says. “My feet hurt, and I feel like I’ve got about five pounds of grease on me. . . . If you stand over that grill all day, it feels like it’s going to drip off of you.”

When the documentary premiered on public television nationwide last summer, it offered a moving profile of the growing number of women like Sereda in eastern Kentucky who have found themselves trapped in low-paying jobs without pensions or health insurance. But a look behind the camera provides a glimpse of a group of people from the Southern Appalachians who have found a way to tell their own stories, producing independent media to provoke debate about important issues.

Fast Food Women was produced by Appalshop, a media center founded 23 years ago to examine regional issues and document the traditions and art of Appalachia. Through film, radio programs, photos, records, and theater productions, the center strives to show the people of the Southern Appalachians “pursuing that which is important to all of us: a chance to work, to live in health and peace, to share our lives with those we love, and to create and sustain that which is beautiful.”

Anne Lewis Johnson, the producer of Fast Food Women, is eating lunch with Mimi Pickering, another Appalshop filmmaker, at the Courthouse Cafe in Whitesburg. During the meal, they discuss the importance of independent media — and some of the difficulties in getting people to watch or listen to thoughtful work.

“I want to see people get involved in social change, and get a handle on what I see as really horrible things going on,” says Johnson. “That’s why I do what I do.”

“I don’t think there is a mass audience of people interested in social change,” Pickering says. “It’s hard to get challenging work watched by a lot of people. People watch television to relax, to vegetate. After a hard day at work, they don’t necessarily want to see children killed in India, or problems in the inner cities.”

“I think Mimi is right,” Johnson says. “People are real apathetic. They think that what they do isn’t going to matter. But I’m constantly thinking we all need to be smarter. The demands are so much more now. We’ve got to figure these problems out or there are going to be a lot of people who just don’t make it.”

Knowing People

The problems of “people who just don’t make it” are evident after lunch, as Johnson and Pickering walk the four blocks to Appalshop — all the way on the other side of town. They pass empty storefronts, an indicator not only of a slack economy, but of the presence of a Wal-Mart on the edge of town. Because the coal economy has been so erratic, the area around Pine Mountain has never been an easy place to find stable work.

For most, it is not an easy place to live. The region lacks clean water, decent schools, and adequate health care. Many local officials are in the pocket of the coal companies. Outside corporations own more land than local residents. Such conflicts between how life should be and how it really is have provided the focus for many Appalshop documentaries:

▼ On Our Own Land documented abuses of the broad-form deed, drawing intense criticism from coal company representatives.

▼ The Big Lever exposed corrupt political practices in Leslie County, Kentucky.

▼ Buffalo Creek Flood investigated why Pittston Coal Company didn’t act to fix a dam before it burst in 1972, killing 125 people and destroying entire towns.

Appalshop resides in a cedar-sided, three-story building that in the past has served as a Dr. Pepper bottling plant, a laundromat, and a pizza parlor. Renovated in 1980, the building now holds an art gallery, conference room, 150-seat theater, film and video editing rooms, radio station, recording studio, and offices.

On the second floor, Herb Smith is preparing a cup of tea before he begins editing his new film about the economic history of Appalachia. Like most of Appalshop’s 32 full-time employees, Smith is from the region. He grew up in Whitesburg and helped found the media center in 1970.

Smith says he has encountered little suspicion from local residents about his independent status. “It is actually pretty acceptable here to be alternative. The notion that you’ve got to be with a television station or in the structures that exist, I don’t find that being too much of a problem around here. The populace is outside of established structures, so they kind of expect you to be. In fact, if I were traveling as the local CBS affiliate or Kentucky Educational Television, I actually think it would be more of a problem dealing with the people we deal with.”

Living and working in the same area also gives Appalshop an advantage over outside, better-financed commercial media, Smith says. “By living and working here, we are able to spend a lot of time with people. If you fly a crew from New York to Whitesburg, you are talking about shelling out several thousand dollars a day. If you sit around on the porch and talk to the people you’re interviewing, it’s money. The most expedient thing is to not get to know the people. The heat is on most producers to arrive, rip off the footage, and get the hell out.

“Recently, I went up to the head of Cram Creek to interview this woman who was 90 years old. When I got there, she said, ‘Herbie, I just don’t feel like it today.’ I had the camera, I had everything in place. We talked a little bit. She talked about what was going on in her family. We didn’t shoot anything. Then, when we came back, it was a wonderful interview. I know if I really pushed it, that it would have been horrible for both of us. I think that is the main advantage of being alternative.”

Radio Free Appalachia

Down the hall in the recording studio, Maxine Kenny edits a feature for Mountain News and World Report, a weekly news and cultural program produced by WMMT, the community radio station at Appalshop. Kenny, who serves as public affairs director for the station, moved to eastern Kentucky from New York in 1969 to help improve health care in isolated communities. She recalls her frustration at trying to inform people in mountain hollows about public meetings.

“One of my fantasies at that time was to have a radio station. I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have a guerrilla radio station that we would just put in an old van, drive throughout the mountains, and get into somebody’s frequency?’ It wasn’t a realistic fantasy, but we used to joke about it. Never in my wildest dreams did I think that 23 years later I would be working on something that probably is the closest thing one might call to Radio Free Appalachia.”

Kenny is one of five staff members and 45 volunteers who provide programming for WMMT. They produce in-depth news reports, live shows, call-in programs, remote broadcasts from surrounding communities, and a range of music from traditional mountain music, to blues, folk, jazz, pop, rock, rap, and international.

“A lot of the public radio stations you listen to could be anywhere in the country,” Kenny says. “There is a real sameness on public radio. We don’t suffer from that. We don’t try to hide the regional flavor of what we are talking about here. We don’t try to fix people’s language up. We’re really minimalists when it comes to narration and analysis. That is in keeping with Appalshop’s purpose of allowing people to have a voice here in the mountains.”

The straightforward, no-gimmicks style distinguishes all of Appalshop’s work from most media. Anne Johnson, the filmmaker, uses an unnarrated style for the programs she produces for the Headwaters television series broadcast by Kentucky Educational Television.

“In some ways, Headwaters is very alternative because of the unnarrated style,” she says. “It is experimental in some ways because it is just ordinary people, like somebody who works in a fast food restaurant. But it seems less alternative than having people with polka dots on them dancing around the stage to some kind of electronic music. I don’t think that alternative media has to have a wild and woolly aspect to it. It can be fairly accessible and still be alternative because of the subject matter, the people, and the way it is made.”

Despite differences of style and content, Appalshop shares two major hurdles with other media: finding money to produce its work, and finding an audience to watch it.

Appalshop has always had to scramble for money. The media center evolved from the Appalachian Film Workshop, started in 1970 with funds from federal War on Poverty programs. The name was condensed to Appalshop as it expanded to include June Appal Recordings and Roadside Theater. In its first decade, the center was fortunate just to meet the payroll. At one point, Appalshop employees went without a paycheck for several months.

Appalshop now boasts an annual budget of $1.7 million. It raises money by performing plays, selling its records and films, and applying for grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, state arts councils, and private foundations. “Our track record helps us a great deal,” says Ray Moore, financial administrator. “Our work is not too terribly controversial. We have a record of doing good work.”

The center has also found a broad audience for its work. Public television stations throughout the country have broadcast its films and videos. Film festivals throughout the world have honored its documentaries. Colleges, universities, libraries, and community groups use its programs to educate people about the region and to spur debate. Audiences nationwide attend its touring plays and workshops.

This past summer, Fast Food Women was broadcast nationwide by public television stations as part of P.O.V. (Point Of View), a series featuring work by independent filmmakers. The previous season, P.O.V. included another Appalshop production, Chemical Valley.

“The quality of their work is extremely high,” says Ellen Schneider, executive producer of the public television series P.O.V. “The issues they deal with are critical. They have the ability not only to focus on a story, but to engage national attention with a far broader appeal. That’s unusual. Appalshop is the epitome of what regional work can do.”

Dee Davis, executive producer of Appalshop Films, agrees. “There are always the problems of developing the audience and funding, of getting by in a place that is as economically hard-hit as this area,” she says. “But the most difficult thing in the world is to do good work. If we are able to do good work, then these other challenges aren’t as daunting. The continual challenge is that the work we produce will speak to people around the country, in ways that people will understand, about issues that are important.”

—Nancy Adams

WMNF

Tampa, Fla.

When a handful of local residents got together back in 1977 to start a noncommercial, alternative radio station in Tampa, few people gave it much chance of succeeding. Even those sympathetic to the effort doubted that a station offering diverse and progressive programs on politics and culture could survive in such a conservative Southern town.

“It’ll never work,” people said. “Somewhere else, yes; Atlanta, maybe. But not here.”

Yet in this coastal haven of powerful Southern families and transplanted Northern executives, WMNF has flourished. The non-profit station aims its programs at low- and moderate-income people — women, blacks, blue-collar workers, senior citizens, and college-educated professionals. At 88.5 FM — “the extreme left of your radio dial” — the station has become an institution of alternative voices for 100,000 listeners a week. More than 5,000 contribute to the station each year to keep it on the air.

WMNF goes beyond the classical music of many public radio affiliates, providing a model of truly community radio. The station trains local residents to do their own shows, and local news reports invariably include the voices of environmental activists, union representatives, farm worker advocates, and others whose views are typically excluded from traditional newscasts.

Indeed, the success of the station has made it a focal point for the progressive community in Tampa. “Any event you go to, if there’s a group of people who are politically or socially aware, you’ll find someone from WMNF there,” says staff member Mercedes Skelton. “I was able to find people of like mind here.”

WMNF was born in rebellion 15 years ago, when the president of the University of South Florida ordered its student-run public radio station to cease playing rock ’n’ roll. It was bad for the school’s image, he told them. Play classical music.

Instead, one student began researching what it would take to start up an independent station. He contacted the Association of Community Organization for Reform Now (ACORN), and they sent an organizer to help raise money. WMNF went on the air a few hours every night starting in 1979.

Today the station is on around-the-clock. Its 100 volunteers far outnumber the seven paid staff members and exercise a great deal of collective power despite their diversity. They include retirees, teachers, an airport shoe shiner, doctors and lawyers, city workers, architects, post office employees, advertising executives, United Parcel Service delivery people, and college students. Young and old, black and white, married and single, gay and straight, feminist and Young Republican — all work together to run the station from an old house amidst posters of musicians and revolutionaries, a homemade plywood box housing an Associated Press machine, three recycling bins in the break room labeled for glass, metal, and paper, and a couple of dogs by the transformer out back, waiting for the end of a volunteer’s shift.

Some volunteers have been coming in for more than a decade to do the same programs every week. The regular schedule includes reggae, polka, Jewish folk music, bluegrass, Latin jazz, Dixieland, electronic music, Sixties and Seventies psychedelia, world beat, gospel, Celtic and British folk music, rhythm-and-blues, and new music.

“It’s the only radio station in the area with a serious commitment to music as an art form instead of just selling tires and gas,” says Logan Neill, a long-time volunteer and co-owner of the State Theater in neighboring St. Petersburg.

The station also offers volunteer-produced public affairs programs, including some aimed specifically at women and African-Americans. Volunteers are currently planning “Out in the Open,” a public affairs show for gay, lesbian, and bisexual listeners.

“Radio as it’s practiced now in most big cities is very narrow cast,” says Lynn Chadwick, president of the National Federation of Community Broadcasters. “WMNF has a broader target and they seem to be hitting people in a wide range of groups.”

There have been some notable failures, like the attempt to expand Latin music programs. Negative audience reaction — in this case, death threats — prompted WMNF to drop its forays into Cuban music and to quit playing die folk music of a Chilean killed in the 1973 coup. “We backed away from that and just played Puerto Rican salsa, but nobody donated to it,” recalls news director Rob Lorei. Programs without listener support disappear. Latin music is now down to a one-hour weekly show of Brazilian jazz.

The biggest controversy in recent years came when a former station manager tried to boost donations from local businesses by emphasizing their financial sponsorship on the air. Volunteers and listeners — ever alert for signs of commercialism on the advertising-free station — feared that companies might exert unseemly pressures if given the upper hand over listeners. Their view prevailed.

Business contributions to the station now total less than $5,000 — a fraction of its $600,000 annual budget. Most of the money comes directly from listeners. “That’s the safest way to make sure there’s no taint on our programming,” says Lorei.

— Linda Gibson

WWOZ

New Orleans, La.

Hazel Schleuter acknowledged National Mule Day in October by devoting her popular Sunday morning radio show to songs about mules and donkeys.

It is the kind of thing devoted listeners in the New Orleans area have come to expect during the 12 years that Hazel has been on the air, sharing her vast knowledge — and equally vast record collection — of old-time country and bluegrass music.

And it is the kind of thing that has made WWOZ-FM one of the most unique community radio stations in the country.

The station debuted in early 1980 in cramped quarters above Tipitina’s, a bar in Uptown New Orleans at the intersection of Napoleon Avenue and Tchoupitoulas Street. A group of people who had donated money to start the bar applied for a radio license, and before long the airwaves were filled with a rich gumbo of New Orleans rhythm and blues, traditional jazz and brass band music, and Caribbean melodies.

“Not only do we seem to be effectively fulfilling our mission to protect and preserve the musical heritage of New Orleans,” says station manager David Freedman, “but WWOZ inherits the magic of the city — the musical magic of one of the world’s greatest musical cities. It is a heady and challenging mission.”

The challenge is not an easy one. When Freedman took over in September, he became the tenth manager of the station since 1987. WWOZ has been plagued in the past few years by internal bickering and by outside studies recommending more mainstream programming.

“We are not going to go mainstream,” Freedman declares. “That is not what we are about. I have not made a single on-air personnel change since I have been here. From the audience response, that is not what we need to do. We need to fine-tune some programs, but mostly we need to establish stability in the role of station manager. I hope to be here for a long time.”

A native of New Orleans, Freedman has more than two decades of experience in community radio. In 1972, he founded the pioneer community radio station in the nation — KSUP in Santa Cruz, California — which later served as a model for WWOZ.

Freedman says he is determined to keep alive the rich gumbo of volunteer programs that makes the station distinctive. One of the first volunteers was Vernon Dugas, who died last January at the age of 56. Dugas, who supported his family as an iron worker and over the years collected thousands of New Orleans rhythm and blues records, tuned into the station one night shortly after it went on the air and immediately volunteered to share his rich legacy of music. Known as the Duke of Paducah, his strong Ninth Ward Yat accent, and his unflagging love of New Orleans music and those who make it, made him a local celebrity.

In 1984 the station relocated to more spacious quarters in Armstrong Park, just outside the French Quarter and a few blocks from the old Cosimo Matassa recording studios where everyone from Fats Domino to Little Richard to Ray Charles cut some of their earliest records. In classic New Orleans style, the crosstown move was accompanied by a Mardi Gras parade complete with brass bands, second-lining, and street chanting.

According to Freedman, the station has benefited from the Blueprint Project, a program put together by American Public Radio and the National Federation of Community Broadcasters to support stations like WWOZ, WRFG in Atlanta, and WDNR in Miami. Experts with the project who studied WWOZ zeroed in on its major problem: the inability to keep a station manager. Managers came and went over the past four years, mainly because each seemed to have a different concept of how to change the station.

“My concept is not to change the station, but to improve it,” says Freedman. “I want to strengthen programs that might not be as strong as they should, but I also want to retain the major mission — to give the audience the rich diversity of New Orleans music.”

Since the move in 1984, the station has been run by the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation, the guiding force behind the world famous New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. On the air seven days a week, WWOZ offers a rich brew of contemporary and traditional jazz, New Orleans music, blues, gospel, Irish music, Latin music, country, bluegrass, Cajun, women’s music, swing, African and Caribbean, Brazilian and reggae.

The diverse programs create broad support. When the station conducts its annual on-air fundraising drives, guests like Dr. John and Irma Thomas drop by to sing and encourage listeners to contribute to the station. And just in case someone’s favorite music has been missed, the station broadcasts an eclectic two-hour show each weeknight called — what else? — The Kitchen Sink.

—Richard Boyd

PIRATE RADIO

Everywhere, U.S.A.

The sign in the front yard along Cornwallis Road read, “Tune Your FM Radio to 98.1.” Motorists in Durham, North Carolina who tuned in to the new station heard Christian programs. They also heard a station that was operating without a license.

The station was one of dozens in communities across the country that broadcast on the FM dial using small, unlicensed transmitters. Known as pirate radio — or the free radio or micro-radio movement — they are run by individuals or groups who bypass the Federal Communications Commission and go on the air without regulatory approval. Like the Durham station, many reach only half a mile, last only a few weeks, and don’t attract much attention.

But not all unlicensed stations are so innocuous. Mbanna Kantako, a 33-year-old public housing resident in Springfield, Illinois, operates WTRG-Black Liberation Radio from his home using a one-watt transmitter, a cassette deck, a telephone, and a few odds and ends. Kantako, described by one of his colleagues as “black, blind, and broke,” broadcasts a mix of music, political speeches by activists, interviews with local residents, and reports of police activity in the community.

Not surprisingly, the station has had its share of trouble. Three years ago Kantako was fined $750 and ordered off the air by the FCC. When he refused to pay, the commission took him to court and won an order shutting him down. Kantako defied the order, however, and continues to broadcast. So far, the FCC has not enforced the ruling.

WTRG is not alone. Another affiliated station went on the air in Decatur, Illinois in 1990, and others are planned for Richmond, Virginia and Birmingham, Alabama. Kantako estimates that there are as many as 4,000 micro transmitters in operation, most broadcasting commercials for local businesses.

Nevertheless, micro-radio is far from constituting a popular movement. King Hall, an FCC Field Operations Officer, says a few unauthorized stations are reported from time to time, but “the reports are rare.” Penalties for unauthorized broadcasts can be as high as $10,000. Enforcement, however, does not appear to be aggressive.

For most people, the cost of operating a legal station is prohibitive. Starting the smallest broadcast station available — 100 watts — costs at least $50,000, if an uncontested frequency is available. Buying an existing station costs at least $500,000. Starting a first-class micro-radio station, by contrast, costs less than $1,000.

There is no shortage of information about how to do it. A recent meeting of the Union for Democratic Communications, for example, experimented with a small transmitter made from scratch for about $30. The device could be heard more than a mile away. For the more technologically timid, a California company called Panaxis offers a transmitter kit and how-to-do-it books for under $800. Paper Tiger Television offers an instruction book and a video on how to build a transmitter. Mbanna Kantako also has a video showing how to assemble a micro-radio station.

Some pirates have also considered micro-television, but the movement was stalled in 1986 when the FCC sued to stop the sale of an imported transmitter called WEE-TV. The small device, which sold for about $150, could send pictures and sound from a video camera or VCR to a nearby television set. As with any transmitter, though, WEE-TV could be paired with a small antenna to reach much farther than “a nearby set” — broadcasting to TVs in homes throughout a neighborhood or community.

— Jim Lee

Tags

Kathrandra Smith

Nancy Adams

Linda Gibson

Richard Boyd

Richard Boyd is a staff writer with the Times-Picayune in New Orleans. (1988)

Jim Lee

Jim Lee is a professor of radio, television, and motion pictures at the University of North Carolina and a member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1992)

Jim Lee is news director at WVSP, a non-commercial, listener-sponsored radio station in Warrenton, North Carolina. (1978)