This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 4, "Fast Forward." Find more from that issue here.

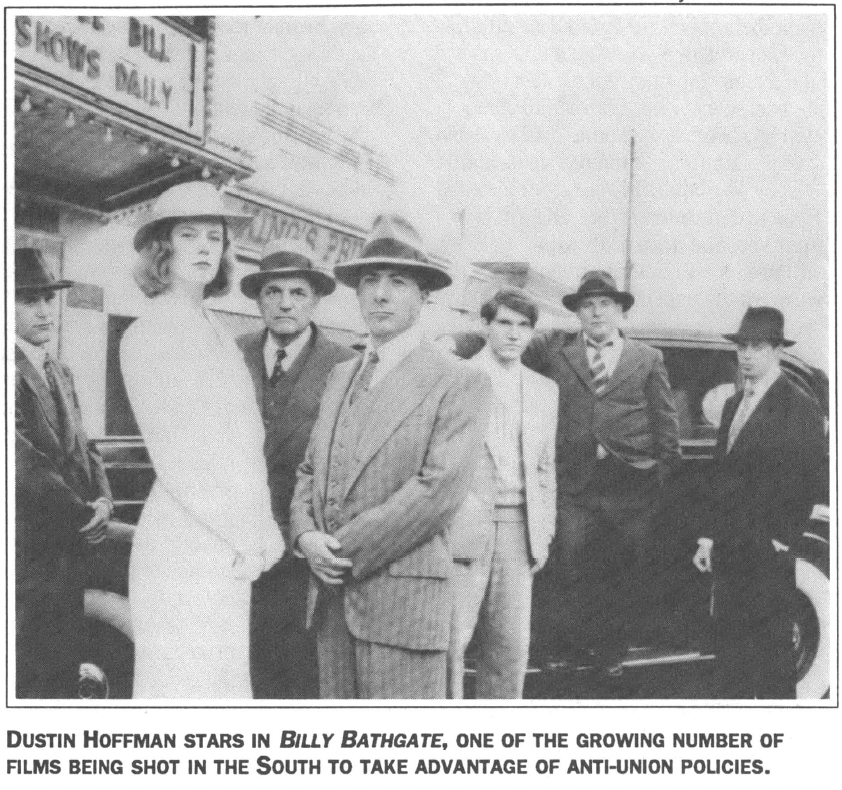

Dustin Hoffman stood on the main street of Hamlet, North Carolina looking every bit the star. Dressed in the dapper attire of a 1920s gangster amidst a lavish set bustling with antique cars, camera crews, and adoring fans, the big-name actor was on location in the small-town South to film Billy Bathgate, a $56-million Hollywood production.

The big-budget movie created quite a stir in Hamlet, a town of 6,500. “It turned out to be a pretty big deal,” recalls Police Chief Terry Moore. “The actors were more accessible than people expected them to be, particularly Dustin Hoffman. He signed a lot of autographs. It was exciting to see the town in the movies.”

Before the movie could make it to theaters, however, less glamorous images of Hamlet were appearing on screens across the country. Eight months after the film crew left town, a fire at the Imperial Foods poultry processing plant killed 25 workers and injured 54. The factory owner later pled guilty to manslaughter, admitting that he had padlocked exits to the plant to prevent workers from stealing chickens.

In a tragic irony befitting a Hollywood production, the film and the fire were linked by more than a common location. Both the movie production and the poultry plant had flocked to Hamlet to take advantage of anti-labor policies that leave workers at the mercy of their employers. Imperial Foods was lured to the town from Pennsylvania — and Touchstone, a Disney subsidiary, was drawn from Los Angeles — by “right to work” laws that keep North Carolina wages low by barring the doors to unions.

The term “runaway shop” has been in the news for years as increasing numbers of manufacturing jobs have fled the heavily unionized North. Now the film industry has joined the flight to the South, shooting more and more movies on location in states like Texas, Florida, and North Carolina. All three states have right-to-work laws — and all three are cashing in on the growing number of film productions fleeing Los Angeles and New York in search of cheap labor.

According to a survey by Hollywood Reporter, California still ranks first for money spent on film production, taking in more than $4 billion in 1990. New York is second with $2 billion. But Southern states are making significant inroads into the movie business. North Carolina now ranks third with $426 million, and Florida finishes fourth with $294 million.

The industry counts on young workers desperate enough to travel to Southern locations, taking a cut in pay and benefits in return for steady work. “The name of the game is still getting three square meals,” one low-budget producer told the trade journal Variety. “Assume that you earn $1,500 a week as a lead carpenter, but now you’re getting $1,250 — even though the producer isn’t paying pension and welfare. On an $8 million movie shooting in North Carolina, who cares?”

Steady Work and Good Pay

To better understand the role that anti-labor laws play in the flight of film production to the South, it is necessary to look at the history and structure of the motion picture industry.

Movies have always been a labor-intensive commodity. Despite often-lavish productions, they require few raw materials: several miles of film stock, some rented equipment and costumes, perhaps a few explosives and some cars to use them on. For the most part, producers spend their money on people, hiring scores of actors and editors and technicians to work for a limited period of time.

In the movie industry, accountants call those who work in technical and manual trades “below the line” employees. Below-the-line workers — including lighting and sound technicians, painters, plasterers, make-up artists, chauffeurs, and animal trainers — generally comprise about 95 percent of all employees involved in production.

Between 1920 and 1950 — the golden days of the Hollywood studio system — many below-the-line employees worked full-time, helping to turn out the steady stream of films that changed weekly at local theaters. For such workers, Los Angeles was one big company town; whether they worked for 20th Century Fox or Warner Brothers, wages and conditions were pretty much the same. That was because all below-the-line workers belonged to one of several labor unions, most of which were affiliated with the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees (IATSE).

Thanks to the union, film studios resembled self-contained cities bustling with plumbers, carpenters, masons, hair dressers and even blacksmiths. Most could count on steady work. It was, as the saying goes, nice work — if you could get it. But you could not get it without a union card.

Things hadn’t always been so good for film crews. The motion picture industry started out at the turn of the century in New York City, where the theater business provided a ready supply of skilled labor. By 1910, however, the fledgling industry began moving film production to Los Angeles, a notorious open-shop city with a well-oiled union-busting machine ready to take on any labor organizers.

Backed by the anti-union Los Angeles Times, motion picture producers in Los Angeles paid workers half the going rate in New York. They worked employees long hours without breaks, cheated them out of wages and benefits, violated safety rules, and blacklisted union organizers. When workers called strikes to organize the studios, producers drew on a reserve supply of unemployed strikebreakers to keep production moving.

The union had a notorious history of its own. During the 1930s, IATSE was run by the Frank Nitti crime family, which used the union to steal from members and to demand payoffs from producers. In the late 1940s, union leaders pushed the House Un-American Activities Committee to blacklist workers and helped set Ronald Reagan on the path of rabid anti-communism. In many cities, the union squelched local union autonomy and strong-armed theater managers who refused to hire union projectionists.

Nevertheless, IATSE offered workers the best hope for fair and equitable treatment. With the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, workers won the right to bargain collectively with employers. Within a decade, the motion picture industry was completely unionized — and IATSE emerged as the dominant union for nearly all craft workers.

“Cheap Everything”

As workers were strengthening their bargaining position, however, the industry was undergoing another major upheaval. In 1948, under pressure from the Justice Department, Paramount and the other major studios agreed to sell off their theater chains to independent firms. At the same time, television began its meteoric rise from a technical novelty to the dominant mode of mass communication. Motion picture companies scaled back their operations, sold their studios to independent producers, and eliminated their full-time technical staffs.

In essence, large companies like Warners, Fox, Paramount, MGM, Universal, Columbia, United Artists, and Disney shifted their focus from making films to distributing films and TV programs around the world. Although they still produced a few films each year, they increasingly depended on independent producers for a steady supply of movies and videos.

To fill the gap left by the big production companies, new independent enterprises arose. Small firms were often formed to make a single film or a limited number of films based on special financial arrangements with big institutional investors.

IATSE adjusted to the changes by requiring producers to hire workers from a roster based on seniority. The union also negotiated specific job categories and work rules to safeguard jobs. Although the independent producers did not formally sign agreements with IATSE or other film unions, they often used union workers and paid union wages.

But as competition among the independents has heated up in the past two decades, they have begun seeking ways to cut costs. And it didn’t take long to hit upon the most obvious budget-cutting tactic: simply film away from Los Angeles, out of sight of organized workers. Cannon is the largest company to use this strategy, but hundreds of smaller companies have followed suit.

Billions of dollars are at stake — and most of it comes out of the pockets of workers. By fleeing Los Angeles, non-union producers can hire fewer below-the-line workers, pay lower wages, contribute nothing to union health and pension funds, and ignore union-negotiated work rules. Industry estimates put the total savings for a single non-union film at 25 percent. With production costs averaging more than $10 million for a film, the savings are enormous.

“A lot of the Hollywood media love to jump up and down saying we promote cheap labor,” says Bill Arnold, who lures moviemakers to North Carolina as head of the State Film Office. “That’s not true. We promote cheap everything — cheap labor, cheap food, cheap accommodations.”

Still, Arnold acknowledges, low wages have a lot to do with the movies moving South. “Our right-to-work laws allow producers to stretch their budgets by picking up local workers who are not necessarily union and who may make lower wages,” he says. “And that spreads the budget out. When 20th-Century Fox made the movie Reuben Reuben here in 1985 for $3.2 million, the producer made the comment that it could not have been made in Los Angeles for under $10 million.”

The lucrative savings have spurred the major studios to get in on the union-busting act. Many studios now initiate projects and then job them out to independent companies that can gain more concessions from the unions. The industry calls such back-door deals “negative pickups.”

“I had a project at Disney,” one producer told Variety. “They wanted to make it for $6 million, but they felt that they couldn’t make it at the studio for less than about $12 million. They asked me to call it Blankety-Blank Production, which would become a pickup down the line. That way we could avoid the unions, they could cut the cost, and we’d all see our profits sooner.”

Non-Union Ninja Turtles

Southern states like Texas and Florida were among the first to cash in on the anti-union trend in the film industry. The Texas Film Commission has been especially instrumental in attracting movie productions to the region. Founded in 1972, the state-sponsored commission launched a high-powered sales job with an advertising campaign and personal visits to Los Angeles and New York. The goal: use the state’s lax labor laws and “pro-business” climate to lure big moviemakers to Texas.

Ellen Justice, who studied the emerging film industry in Texas, cites industry sources who declare that making films and television commercials in the South saves money for producers. The biggest savings, according to most producers, comes from cutting the number of workers on the job.

“Picking up equipment in Hollywood would require the services of a grip, an assistant cameraman, plus two Teamsters,” writes Justice. “In Texas, one or two crew members routinely pick up equipment without assistance from the Teamsters.”

For large productions that require the use of hundreds or thousands of background actors called extras, producers who move from Los Angeles to Texas can cut costs even further by avoiding the Screen Extras Guild. In Texas, there is no union for extras — and thus no union wages.

The Florida Film Commission has been using the same tactics for several years, attracting scores of big-budget productions to new studios in Miami and Orlando. Such state-funded commissions essentially serve as agents for filmmakers — using taxpayer money to scout locations and ensure trouble-free shoots.

Dino DeLaurentis went a step further, attempting to set up a 16-acre non-union studio in Wilmington, North Carolina. The project fell through, but Cannon, Caroloco, New World, and other “mini-major” production companies have set up non-union shops on a smaller scale in other states. Studio complexes are currently in the planning stages in Atlanta, Memphis, Houston, New Orleans, and Jacksonville.

North Carolina has been the biggest beneficiary of the film industry flight. Since the State Film Office was formed in 1980, nearly 200 feature films have been shot on location in the state. “The three most successful independently produced films in history — Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles I and II and Dirty Dancing — were all shot here,” boasts Bill Arnold, director of the film office. “Twentieth-Century Fox shot The Last of the Mohicans totally on location in North Carolina at a cost of $46 million.”

Such productions add up, Arnold notes. “Counting all production — films, videos, television series — the total economic impact on the state is something in excess of $2.5 billion. North Carolina has ranked either second or third in the country for six of the last seven years for total revenues derived from filmmaking.”

Arnold cites several reasons for the film boom in North Carolina, emphasizing the variety of the state’s climate, land, and buildings. “The terrain and architecture in certain spots resembles New England. Rather than endure Boston during January, producers are able to move down to North Carolina and shoot in a much more comfortable climate and still get the same New England look.”

But the bottom line is money. “North Carolina is a right-to-work state, which seems to be important to certain producers,” he says. “We now have a resident workforce of 1,000 technical people who don’t do anything but work movies. We have more movie studio complexes and sound stages than any state besides California.”

Quiet on the Set!

Today an estimated two-thirds of all feature films made in the United States — including big-budget, Academy Award winners like Dances With Wolves — are non-union productions. Most are made on the sly throughout the South, with little pre-production publicity. Big-name actors are given roles — and a share of the profits — on the condition that they will not reveal that the picture will be shot away from Los Angeles under non-union terms.

“There are situations where you look at a picture and say it needs to be done non-union,” explains one top studio executive who wished to remain anonymous. “We do that, but we do it out of town. You try it here in Los Angeles and you’ll get organized and wind up with a grievance.”

In most cases, however, film unions have been forced to accept cuts in pension and health care benefits. Like other labor organizations, their members are faced with the dilemma of either giving up hard-won benefits or losing their jobs to the non-union South.

Indeed, the region’s greatest value to producers may be as a bargaining chip with the unions. By making a significant number of movies in Texas, Florida, and North Carolina, the producers have managed to weaken the unions on their home turf. Unions now routinely provide significant concessions for films made in Los Angeles and New York. They have revamped their roster system to allow producers to hire a wider range of people. They ignore work rules to make inroads with low-budget producers. And when films move from Los Angeles to other locations, the unions no longer require that entire crews be taken along.

Slowly, though, the unions have begun to fight back. When unions have found out about big productions outside Los Angeles, they have taken action to improve wages and conditions. On some Southern locations, organizers have disrupted production by making noise and using mirrors to reflect sunlight into cameras. In September, the Teamsters disrupted filming of The Real McCoys in Atlanta to force the studio to recognize the union. In 1989, IATSE organizers chased Robo Cop II to Texas and managed to get some concessions from the producers.

“The idea is not to harass, but rather to get those film crews covered by union wages, working conditions, and benefits,” says Bruce Doering of Local 659. “We got the film crew on The Last of the Mohicans in North Carolina to sign cards saying they wanted IATSE to represent them. It was like a scene from Norma Rae. Local television cameras came out to cover it. The producer tried to intimidate the crew by saying, ‘You’re not really for the union. Everybody who’s for the union, stand up.’ Everybody stood up.”

Moviemakers may also find that they are wearing out their welcome in small towns across the region. Local residents and businesses in towns like Hamlet earn little from Hollywood films like Billy Bathgate beyond the thrill of seeing movie stars.

“Everybody enjoyed it at first, meeting the actors and the big-name people,” says Hamlet Police Chief Terry Moore. “But as time wore on and the roads remained blocked, folks couldn’t come and go on Main Street like they wanted to. There was a lot of inconvenience, and local storeowners said it hurt their business because people couldn’t get to their stores.”

Townspeople were shocked by “how much money was wasted on the film,” Moore says. “It was just phenomenal. They spent so much fixing up a hotel here — putting up period wallpaper and carpeting and building an entire miniature golf course — and then none of those things made it into the movie. It was too bad it turned out like it did. It was a tremendous flop.”

In the end, says Moore, few in Hamlet were sad to see the film crew pack up and go. “It turned out to be like anything else,” he says. “Once the excitement wore off, people grew a little tired of it.”

Tags

Mike Nielsen

Mike Nielsen teaches communications at Wesley College in Dover, Delaware. (1992)

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.