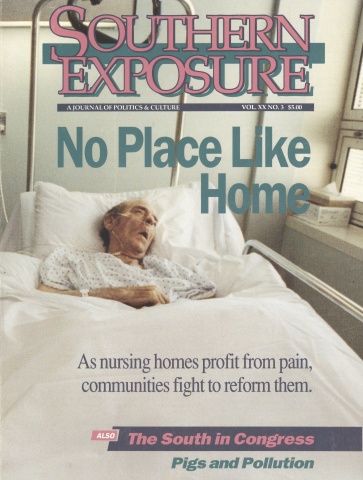

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

“I hope I die before I have to go to a nursing home," a friend in her twenties told us the other day. It is the kind of comment we hear all too often of late. Most of us, it seems, are just plain afraid of nursing homes. They have come to represent everything we fear about growing old—sickness, pain, long and lonely days spent in a cold and impersonal institution, death.

Yet as the population as a whole grows older and those born during the baby-boom generation reach middle age, more and more of us are having to care for elderly parents at home, or go broke paying nursing home bills. In 1988, the country spent $53 billion providing long-term care for the elderly. Fewer than 20 cents of every dollar went to care for the needy in their own homes. Most went to pay the expenses of the 1.7 million Americans in nursing homes—a number expected to reach 5.3 million by the year 2030.

It doesn’t have to be that way. All across the South, people are coming up with healthier and more humane ways to care for their parents and grandparents. One program uses social workers to connect the elderly to medical care and social services while they are still well enough to live at home. Another enables elderly volunteers to care for their next-door neighbors. Others provide health care in the home, or create non-profit housing centers or clinics that are owned and operated by the community.

Whatever the approach, the six alternatives profiled here all have one thing in common: They strive to help older citizens keep their homes, their independence, and their dignity. They prove that doctors, nurses, ministers, social workers, and neighborhood volunteers can work together to provide love, respect, and affordable care for the elders of the community. —Eric Bates

Southwestern Aging Team, Pulaski, Virginia

For a while, it looked like Rita Slenker might never make it back to the white frame house with the big Catalpa tree out front.

The house in southwest Virginia had been her family home for almost all of her 75 years. But last spring Slenker wound up in a Maryland hospital with a case of double pneumonia. She coughed so hard she cracked a vertebra, and she was afraid she’d end up in a nursing home.

Instead Slenker came home and stayed there — with the help of Ellen Lamb, a “case manager” from New River Valley Agency on Aging.

Lamb arranged for Slenker to get daily “meals-on-wheels” lunches and weekly visits from a housekeeper. She had grab bars installed in Slenker’s bathtub. And she has helped her keep up with doctors visits and lots of small chores that can be overwhelming for someone whose health has weakened.

“She’s just been so good to me it makes me cry sometimes,” Slenker says.

It wasn’t a lot of help — but it was enough to allow Slenker to take care of herself with some support from her neighbors. And that, says Lamb, is what being a case manager is all about.

The New River agency is one of four participating in a regional program called the Southwestern Aging Team (SWAT). Now in its second year, SWAT has 18 case managers who cover every county and city west of Roanoke. They help elderly people stay in their homes, stay independent—and stay out of rest homes or nursing homes.

Health workers say that many older people don’t seek help until they’re too frail or ill to stay in their own homes. The problem is especially bad in southwest Virginia, where high rates of poverty and illiteracy and shortages of health care prevent many from receiving the preventive medicine they need. Case managers try to link people up with health and social services sooner so they can stay independent longer.

Even so, some people won’t ask for help because they’re afraid social workers will force them into a nursing home. “You constantly have to reassure them,” says Dana Collins, who supervises case managers in Cedar Bluff. “We tell them: No, you’re not going to lose your home. No, they’re not going to take you away.”

Debbie Palmer, executive director of the New River agency, says rest homes and nursing homes have an important place in long-term care, but they shouldn’t be the only alternative for older people. The case manager’s job is “empowering these people to deal with the system.”

Virginia officials and university researchers are studying the project to see if the idea can be expanded across the state. But with an annual budget of $400,000 in federal and state funds, SWAT has already helped nearly 1,000 older Virginians put off or avoid going to nursing homes. A few examples:

Case managers arranged for sitters to care for an 83-year-old widow who fell down two flights of stairs a few months ago. They also found her an amplified telephone to enable her to stay in touch with friends and family despite her hearing loss.

A 76-year-old man with terminal lung cancer who was living in a rundown house received a stove, phone, smoke alarms, and a new front door. Case managers also arranged for “meals-on-wheels” and visits from a local hospice.

Social workers convinced a medical transportation service to provide free rides to the hospital for an 81-year-old woman whose relatives were charging her $100 for the three-hour trip.

“If they put me in a nursing home, I’ll die,” a 97-year-old woman who fell and broke her hip told social workers. Case managers arranged for personal-care aides and a sitter to stay with her, and a church agreed to pick up her utility bills.

Rita Slenker was also afraid she’d end up in a nursing home. Last summer she had gone to stay with a sister in Maryland who had cancer—and then she came down with pneumonia herself. By the time she returned to Pulaski, she had to use a metal walker to get around.

“I couldn’t get out of bed hardly,” she recalls. “It took so long. Painful.” Then she broke two more vertebrae rolling over in bed.

But Slenker has gotten better and better. She gets lots of help from her neighbors, especially a young couple with twin girls. “You just wouldn’t believe how much they’ve done for me. He’s even called me from the store to see if I need anything.”

In evenings when folks are home, she walks outside in her yard, sometimes carrying a cellular phone with her. “I’m doing real good with what help I’m getting now,” she says. “If I can just continue getting better....”

She got home in time this year to see the blue flowers on her hydrangea bush. It was the first time it has bloomed in 15 years. —Mike Hudson

Time Dollars, Miami, Florida

Like most elderly residents of Miami, Daisy Alexander comes from somewhere else. She has no family members nearby to take her to the doctor when her angina acts up, or to clean the house when her arthritic knee swells. Nor does she have the money to pay a professional to do the job.

But the 76-year-old Alexander doesn’t worry. She knows that with a phone call, she can get help from any of a dozen neighborhood volunteers.

She and several neighbors in the low-income housing complex where she lives belong to the Time Dollars Network, a volunteer army of 1,900 who help the poorest elderly residents of Miami keep their independence. The volunteers — most of them retired women like Alexander — drive clients to appointments, clean house, explain Social Security forms, and sometimes just call to check on frail neighbors living alone.

For every hour a volunteer like Alexander works, she earns a “time dollar” — credit for an hour of service from the network that she or a family member can use as needed.

For many, however, credit is immaterial. Their satisfaction comes simply from helping others. “I’m by myself with my husband and I love people,” says Gladys Vazquez, a 59-year-old volunteer. “It’s a pleasure for me to help people.”

Besides, the network serves anyone in need, free of charge. Volunteers know that help is always available, even if they have logged no credit.

Daisy Alexander is one of the busiest volunteers in the program, despite her sometimes crippling arthritis. “It’s very difficult because I walk with a cane,” she says. “But my mind is stronger than my body. When I get out, I forget about my pain.”

Time Dollars was conceived by Edward Cahn, a University of Miami law professor, as he lay in a hospital bed recuperating from a heart attack in 1980. “We had a recession then and lots of people were out of work,” he says. “I was also aware that there were plenty of people who needed care. I asked myself, why can’t we create a new kind of money to get people and needs together?”

His idea won the approval of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which awarded the Time Dollars Network a $1.2 million grant in 1985 to organize in Miami and five other cities. Since then, the program has spread to more than 80 cities in 28 states.

In Miami, the network is scattered among eight retirement housing complexes where most of the volunteers and clients live. A paid executive director oversees the entire network, relying on volunteers to coordinate services from each center.

Cahn set up the program loosely, to avoid any resemblance to more bureaucratic, professional services. Through simplicity, he sought to bring clients and volunteers together as a “family.” Unlike most home-care professionals, volunteers with Time Dollars face no formal screening or FBI checks.

That alarmed state officials, who wanted volunteers to be investigated. But Cahn balked. After five years, he claims, Time Dollars hasn’t had a single incident of theft or abuse.

The agency is equally trusting of its clients. Although it seeks to serve those who cannot afford professional care, Time Dollars has no means test. “This is about what neighbors and friends can do,” Cahn explains. “It’s not about what you can pay.”

A widow with an oceanfront condominium who wants volunteers to serve hors d’oeuvres at her next party will be turned away, Cahn says. But the widow with the oceanfront condo who needs a friend to talk to a couple of hours a week will be welcomed.

The greatest reward for network leaders is seeing clients and volunteers develop close, lasting relationships.

“These volunteers we matched with people in need have become friends,” says Ana Miyaris, executive director of the Miami network. “We don’t have to call them. The recipient calls them. We just open channels between neighbors.”

In the three years since she became a volunteer manager for the network, Gladys Vazquez has seen the number of volunteers in Miami more than double. Yet the program retains its camaraderie — and Vazquez still hears from friends like Daisy Alexander.

“Daisy calls me and says, ‘Gladys, this happened to me. Can you come over?’ These people love us so much. We become like family.” — Cynthia Washam

VIP Center, Anniston, Alabama

Frances Hyde suffers from seizures. She needs round-the-clock supervision — but instead of being confined to a nursing facility, she lives at home and spends each day at the VIP Center, a non-profit program that provides day care for adults.

A full-time staff of four watches over Hyde and 38 other elderly and disabled adults as they sew, work on crafts, sing together, take daily walks, and enjoy outings to a nearby museum, bowling alley, and Wal-Mart.

“This is just about like a second home,” Hyde says. “It’s like my own family.”

Since it opened in Calhoun County a year ago, the center has become a second home to dozens of adults ranging in age from 26 to 84. They include elderly people who suffer from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, as well as younger people who have cerebral palsy or are mentally retarded. The only requirement is that individuals be able to feed themselves and go to the bathroom.

Pam Hall-Gann, the founder of the center, says the program provides an affordable alternative for many elderly residents who require constant attention but don’t need the intensive care of a nursing home. The center charges a maximum of $20 a day to care for clients — compared to an average daily rate of $71 at most Alabama nursing homes.

The center is one of 37 adult day care facilities in Alabama certified to receive referrals from the state Department of Human Resources. The centers voluntarily agree to meet DHR standards in exchange for referrals: Unlike day care centers for children, operations that supervise adults are not regulated in Alabama.

Jude Ledbetter, coordinator of adult services with the DHR in Calhoun County, says the state should monitor adult day care centers to protect clients. “A lot of people are bringing adults into their home to live who shouldn’t be,” she says.

Yet Ledbetter has nothing but praise for the VIP Center, the only facility providing adult day care for the 120,000 citizens of rural Calhoun County. “We’re proud that they opened up and they’re there,” she says. “It does save money and it does prevent nursing home care in many situations.” Not only does the VIP Center provide activities for elderly citizens, but it also serves breakfast, lunch, and a snack during its hours from 6:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. For some clients, those meals are the only food they will eat during the day.

About half the elderly participants receive Medicaid, but the money doesn’t cover all of the costs of the VIP Center. During the past year, director Pam Hall Gann had to pump in about $ 12,000 of her own money to keep the center open. By this fall, she hopes her expenses will not exceed her budget, which runs about $50,000 a year.

Budget woes have prevented Hall Gann from buying a van to transport clients to and from their homes each day. She wishes she had more volunteers to help her mother, who drives clients whose relatives can’t drop them off. Center staff also take clients to visit the doctor, pick up prescriptions, and collect food stamps.

While the center has had a relatively trouble-free year, an Alzheimer’s patient wandered away from the facility a few months ago. Luckily, the police tracked her down, even though she had taken off the identification tag that all clients at the center must wear.

In addition to keeping older citizens out of nursing homes, social workers say, the VIP Center also serves an important emotional need. It is a social outlet for many elderly who might otherwise be ignored.

“For a lot of people, the center is their only contact with the outside world,” says Jude Ledbetter, the county services coordinator. “It gives these people a reason to get up and gives them a sense of self-value.” —Jenny Labalme

Family Service, Roanoke, Virginia

Lera Watkins stayed home with her son almost until the end. She was nearly 78, and she was dying, pulled down by diabetes and congestive heart failure.

Her son, Rick, was determined to keep her home with him as long as possible. It was tough. She got weaker and weaker. Nobody got much sleep. Sometimes she would say: “This is too much on you.” But it was worth it. Every day they shared little things, like sipping morning coffee together as he fried an omelet for her. Knowing the end was near made the small pleasures that much more intense.

Rick Watkins couldn’t have done it without help from his fiancee, his family, his friends — and home-care aides from Family Service of Roanoke Valley.

As many as five mornings a week, aides from Family Service came in and helped with whatever Lera Watkins needed. Along with visiting nurses, the in-home aides gave her son the support he needed to keep his mom at home. Without it, he says, his mother probably would have spent the last months of her life in a nursing home “laying in bed with a TV set overhead. I would have stopped by once a day and that would have been it.”

Instead, she spent only a few days in the hospital before she died March 1.

Family Service has been giving in-home care to the elderly and handicapped for a quarter of a century. The non-profit agency, which also offers family counseling, gets funding from United Way, foundation grants, and other donations. With its $240,000 budget, the agency is able to offer service on a sliding scale, charging clients only what they can afford to pay. Mary Johnson, a social worker at the agency, says fees at Family Service run about half the industry average of $9 an hour.

Home-care aides help clients with grooming, bathing, meals, housekeeping, shopping, and medications. Counselors from the agency can also help with depression or family problems. Although the program once employed 17 nurses and geriatric aides, budget cuts have lowered the staff to eight. Family Service still manages to serve as many as 50 people each month, but the program has a waiting list of at least 20.

“We need more aides,” Johnson says. “We need more funding somehow, someway. If I had five more aides, I could put them out there tomorrow. Sometimes, it’s really difficult to tell someone there is a waiting list.”

Lera Watkins was on a waiting list for a month or so. Then she was visited by home-care aides for nearly two months before she went into the hospital. “They were incredibly professional and helpful — and they genuinely cared for my mother as a person,” says Rick Watkins.

Even after it was clear death was near, Lera Watkins kept fighting. Rick fed her jello with a spoon and gave her ginger ale through a straw. She hung on for 36 hours.

“I’m very proud of what we were able to do,” he says. “I’d like people to know there are alternatives.” —Mike Hudson

Pungo Village, Belhaven, North Carolina

Times are tough in the waterfront town of Belhaven on the eastern shore of North Carolina. The seasonal fishing industry, once a mainstay of the local economy, has receded in recent years. Docks jut out into the ocean, weathered and silent. Many residents commute to Virginia to work in the naval shipping yards, more than three hours away.

One might not expect a community burdened by such economic hardships to pay much attention to elderly and disabled citizens. But the 2,500 residents of Belhaven have managed to accomplish what few other towns, rural or urban, have achieved: They have created a biracial, non-profit community to care for older residents.

Last year Belhaven opened Pungo Village, a complex of 38 apartments for the elderly built around an artificial lake. Staff and community volunteers run a senior center, offer a nutrition program, transport residents to medical appointments, and help them with their personal needs.

Residents also pitch in and look out for one another. Unlike many nursing homes, which are tucked away in some distant field, Pungo Village is located in town — enabling older residents to remain in the community, within walking distance of family and friends.

“It’s easy to visit my relatives, and they can visit me,” says Sylvia Harrington, a resident of Pungo Village. “It’s a nice place, quiet. I like the people. This is my home.”

In its first year, Pungo Village has already become a close-knit community. Residents say they especially enjoy the beauty of the architecture and the comfort of the surroundings.

“There’s a nice pond,” says Harrington. “I don’t like to fish unless I get a bite right away, but my friend likes to fish, so I just stand and watch her.”

Community members credit the Reverend Judson Mayfield with providing the spark for Pungo Village. Since the early 1980s, Mayfield has directed Shepherd’s Staff, a coalition of black and white churches that has provided services to thousands of older residents. The group offers emergency food and clothing, help paying utility bills, and rides to the hospital 30 miles away.

Slowly, Mayfield and other local pastors began to realize that they needed to do more to help isolated elderly citizens. The result was Community Developers of Beaufort-Hyde, a non-profit operation founded to build an alternative community for the aged.

“We were passing out kerosene and blankets, but what people really needed was housing,” Mayfield says. “It quickly became apparent that establishing a community would make a lot of sense.” Obtaining the money to make the project a reality proved difficult, but Mayfield proved equally tenacious. “He is totally dedicated to what he does,” says Shirley O’Neal, coordinator of services for Pungo Village. “If he did not get the funding he wanted, he just applied for another grant or asked for a smaller amount. He would not give up.”

Organizers also had to overcome decades of mistrust between black and white residents in the predominantly black town. “There was a division between both races,” says Janice Ellegor, manager of Pungo Village. “It made it difficult to pull together local resources for the benefit of the whole community.”

Local pastors who had belonged to the Shepherd’s Staff coalition, however, already had more than a decade of experience in working together and building trust across racial lines. Under the leadership of Mayfield, local churches united their congregations around their shared concern for the elderly.

“I was impressed by how the whole community came together in support of this project,” says George Esser, a rural poverty expert who helped to raise funds for the Belhaven project. “When a community is faced with very limited resources, it is a truly integrated effort which is the key to success.”

The black and white residents who live at Pungo Village contribute 30 percent of their incomes for food, housing, and other services. The remaining budget is generated from grants and local institutions.

Community Developers of Beaufort-Hyde is meanwhile planning to build more housing for the elderly in neighboring Hyde County. Once again, the group will depend on churches to unite the community. “If you leave God out of it, you don’t get a thing done,” says O’Neal, the services coordinator. “If you don’t have the moral fabric, you don’t make a bit of progress.”

Observers say communities across the region could duplicate the success of Pungo Village — if government and business would direct more public funds to local, non-profit efforts and less to for-profit nursing homes.

“Poor communities have the leadership they need to provide essential services like Pungo Village, but that leadership must be stimulated through foundations and banks,” says George Esser. “Every rural community in the country needs to have this type of community-owned facility for the elderly.” — Shana Morrow

Hampton Woods, Woodland, North Carolina

Imagine a nursing home where all the stock is owned by local residents — and where all the profits are returned to the home to improve the quality of care for the elderly.

Now picture the nursing home connected to a rest home, a senior center, apartments for the elderly, and a community clinic staffed by doctors, dentists, and a pharmacist.

Finally, imagine the entire operation flourishing in one of the poorest counties in North Carolina — an area long abandoned as unprofitable by private physicians and nursing homes.

Beyond imagination? Not in rural Northampton County, where local residents have created Hampton Woods Board and Care and Retirement Community Inc. The organization runs a non-profit, community-based nursing home and health clinic designed to provide older residents with the best care possible.

The project dates back to 1974, when a group of Northampton citizens concerned by the dwindling number of doctors in the county met with the Office of Rural Health in Raleigh. Officials helped the residents secure loans and grants to build a medical, dentistry, and pharmacy center, as well as to recruit physicians.

With the encouragement and assistance of Dr. Jane McCaleb and other new doctors, citizens began investigating ways to provide better long-term care for the elderly. The result was Hampton Woods, a unique facility that combines a primary care center, a 60-bed nursing home, an 18-bed rest home, and a community of 15 apartments in which residents live independently and prepare all their own meals. Hampton Woods also includes a senior center open to all older residents in the county for classes, parties, and meetings.

“This is state-of-the-art health care,” says Dr. Mark Williams, director of the Program on Aging at the University of North Carolina. “Access to this kind of service in a rural community is really quite extraordinary. Poor people in Northampton County receive the same or an even better quality of health care to what millionaires receive around the world.”

Its unique approach has made Hampton Woods an international model for alternative, long-term care. Williams says he routinely receives calls about the facility from doctors in Cairo, London, and Tokyo. The university sends a team of doctors, nurses, and social workers to the clinic each month to evaluate elderly residents and recommend treatment “This is the first geriatric consulting team based in a rural community in the country,” says Williams.

The key to the success of Hampton Woods lies in its broad-based, community support. More than 2,000 residents contributed a total of $28,000 to get the center started, and scores wrote letters and attended public hearings to make sure the facility got approval from the state.

“When they applied for a certificate of need for their nursing home, they didn’t have any for-profit competitors,” says Bernie Patterson of the Office of Rural Health. “It requires a lot of time and money to compete for a certificate, and a corporation won’t risk that type of investment if residents are united and actively seeking a certificate for their community.”

Hampton Woods has expanded beyond the services provided by for-profit nursing homes by cycling profits back into the home to improve health care. The facility recently received state approval for another 20 beds, and administrators are exploring the possibility of building an endowment fund to expand care for the poor.

“Many people in the county don’t qualify for Medicaid, yet they don’t have enough money for insurance to cover their care,” says administrator Bill Remmes. “These are the people who too often fall through the cracks.”

Reinvesting profits in the facility also allows Hampton Woods to maintain a larger staff than most for-profit nursing homes. The community facility has fewer beds than the average corporate home, yet its nursing staff is 50 percent larger than the average for-profit operation.

More nurses and fewer patients means more care. The state requires homes to provide each resident with 2.1 nursing hours a day; Hampton Woods offers 3.9 hours.

As a community-based facility, Hampton Woods is also more willing than for-profit homes to accept patients who require more care. With long waiting lists for beds, corporate homes have an incentive to select patients who are easier — and therefore less expensive — to care for. Hampton Woods has a higher-than-average number of patients who need intensive, sub-acute care — saving many residents from long, expensive stays in a hospital. “We are indebted to Northampton County residents for their support, so we take patients who need more care,” says Ken Reeb, administrator of the senior center. “We don’t measure our success by profits — we measure it by a higher standard of health care.” — Shana Morrow