This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

Raleigh, N.C. —When Helen Jarrell checked into a rest home two years ago, it seemed like a good place to spend her final years. The facility did not provide around-the-clock medical care like a nursing home, but it had a special unit for patients like Jarrell who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Her guardians thought she would receive extra attention there.

Three weeks later the 81-year-old Jarrell was found hanging from her bed, asphyxiated by a restraining device designed to keep her from getting up.

The state fined the home $3,000. Over the next 14 months, two more rest home residents suffocated in their restraints. In the second case, the home was fined $250. In the third, the state decided that the home was not at fault.

Spurred by the deaths, advocates for the elderly pushed hard for stricter regulation of the potentially deadly devices. They researched the issue, worked with rest home operators, and came up with a compromise rule that would require homes to train staff in the proper use of restraints.

But last spring, when it came down to making the proposal a law, the industry fought it. Home operators and their lobbyists plead poverty, arguing the industry could not afford to pay the estimated $600,000 it would cost for training. State regulators backed away from the measure, saying it would be too much of a burden on the homes to foot the bill.

State officials proved less thrifty, however, when it came to doling out tax money to rest homes. About a month after state regulators abandoned the training requirement, legislators awarded the industry an extra $13 million to cover the cost of care for the indigent elderly. Next year, rest homes will collect nearly $100 million in public funds from the state and its counties.

The double standard is typical of rest homes and nursing homes in North Carolina and other Southern states. Operators of the homes are willing to accept public money — more than 70 cents of every dollar they spend comes from taxpayers — but they are reluctant to accept public efforts to safeguard the health and welfare of the elderly citizens who live in their homes.

Last year, the fiery deaths of 25 chicken plant workers in Hamlet, North Carolina led the state to toughen worker safety programs. By contrast, a review of state records and interviews with regulators, lawmakers, home operators, and patient advocates reveal that the more than 50,000 residents of nursing homes and rest homes in the state continue to receive scant protection.

For years, advocates for patients and their families have been trying to get the state to keep a closer eye on long-term care facilities. But the industry wields considerable political and financial clout in the state, and it uses its power to block reform efforts. Despite task forces, study commissions, lawsuits, and legislation, older citizens who live in nursing homes and rest homes continue to lose their dignity, their limbs, and their lives. And all too often, advocates say, the homes go unpunished. “I think people are dying from neglect and abuse,” says Anne Hardaway, who served on a nursing home advisory committee in New Hanover County. “The state is doing little to prevent it — and even less to punish the homes after it happens.”

Money and Politics

The long-term care industry has long made its living off of public funds. Last year, total government spending on nursing and rest home care in North Carolina totaled more than $550 million. Medicaid, the joint state and federal health plan for the poor, covers the cost of care for about 75 percent of the state’s nursing home residents. A state and county program called Special Assistance pays for about half of all rest home residents.

Despite their dependence on tax dollars, home operators want taxpayers and their elected representatives to stay out of the business. The industry often complains about what it sees as too much regulation, and it fights most new rules vigorously.

“The whole system is based on negative features,” says Craig Souza, president of the North Carolina Health Care Facilities Association, the major nursing home trade group in the state. “The system is there to try to catch you.”

Since state government drafts regulations and sets reimbursement rates, the industry has worked hard to line up allies in the political arena. It has a variety of weapons at its disposal:

Money. Home owners and operators are regular contributors to elected officials and their political parties. A review of state election records reveals that industry representatives and their relatives have contributed at least $71,862 to the Republican Party and the GOP campaigns of Governor Jim Martin and Lieutenant Governor Jim Gardner since 1984.

Home owners and operators are equally generous with state lawmakers. In 1990 alone, industry officials and the nursing home trade group handed out $27,750 to 73 candidates running for the General Assembly. The largest contribution went to state Senator Jim Ezzell, who sponsored a 1989 measure that exempted rest homes and nursing homes from penalties for some regulatory violations.

Contact. Rest homes and nursing homes both have active trade groups with experienced lobbyists who know how to work the halls of the state legislature with the best of them. Since 1989, for example, the rest home industry has contracted with Roger Bone, recently ranked by one public policy group as the fourth most influential lobbyist in North Carolina.

Connections. The state Department of Human Resources (DHR), which is responsible for levying fines against errant homes, is studded with political appointees with ties to the industry. “They seem more interested in protecting the rights of the homes than in protecting the lives of the elderly,” says one county social worker who asked not to be identified.

The head of the department, David Flaherty, is former chair of the state Republican Party. Bill Franklin, former director of intergovernmental relations, is now chief lobbyist for the rest home industry. The head of the department’s Division of Facility Services — the primary watchdog agency for nursing and rest homes — spent much of 1988 as director of the rest home industry trade group. This year, the former Republican mayor of Mars Hill was picked as the division’s deputy director, but was quickly transferred to another state job after newspaper reports disclosed that he had pleaded guilty to Medicaid fraud in 1987.

Inside Track

Close ties between the industry and public officials who are supposed to monitor it are nothing new. In 1981, State Auditor Ed Renfrow issued a scathing report blasting regulators for being too lenient with homes that repeatedly violated the same rules. The report called for modest reforms in the regulatory process.

Renfrow says he was surprised by how state officials ignored the report — until he came to understand that the industry has what he calls “an inside track” to state policy makers.

“It’s a political situation,” he says. “The industry plays both sides of the street. They lobby well and do their homework. I don’t have a problem with that, but there ought to be a balance. Everybody ought to be able to address their government.”

But when it comes to reforming nursing and rest homes, even state lawmakers have a hard time addressing the government. Long after Renfrew’s report was forgotten, state Representative Betty Wiser tried to push some nursing home reforms in the legislature, only to find her colleagues were reluctant to support her.

“I was very much aware of a strong interest on the part of the industry,” says Wiser, who left public office in 1990 after serving three terms in the state House.

A year before she stepped down, Wiser proposed a bill to widen representation on the state Penalty Review Committee, an independent panel of home operators, state regulators, and consumer advocates that meets monthly to review proposed fines against nursing and rest homes. In 1987, the panel was given the authority to fine homes up to $5,000 — a big improvement over the previous system, which limited fines to $10 per violation.

But consumer advocates serving on the panel soon became convinced that the committee needed representation from health professionals who could better interpret shortfalls in care. Wiser proposed adding a geriatric physician, a nurse, a rehabilitation specialist, and a dietician to the panel. Home operators fought the measure, lobbying aggressively in legislative committees. By the time the House ratified it, the bill added only a nurse and a pharmacist to the panel.

What’s more, the industry managed to tack on an amendment that allowed homes to escape panel review for relatively minor violations of health and safety standards.

Wiser blames the industry lobby for weakening the bill. She also faults her colleagues for letting it happen. “My impression is that they were just not interested in it,” she says.

Marlene Chasson, director of the statewide advocacy group Friends of Residents in Long-Term Care, puts it more bluntly. “Everything Betty tried to do got cut to ribbons,” she says. “In trying to strengthen the legislation, it actually came out weaker.”

Closed Door

Blocked by industry lobbyists in the legislature, Chasson and other advocates have tried to reform the industry through the state administrative rules process. Their efforts were bolstered in 1990 when the press began to focus on the state’s reluctance to take action against errant homes. After changes in personnel and procedures at DHR, homes were fined aggressively for several months. But it didn’t last. According to Chasson, regulatory changes designed to protect residents rapidly evolved to favor home operators.

“I think it has come full circle and now they’re leaning toward the providers,” she says. “The state is supposed to be looking out for the residents, not looking out for special interests.”

One of the changes that backfired was a rule designed to give state inspectors more say in deliberations over fines. The state has teams of inspectors who monitor nursing homes, while county social service agencies monitor rest homes. An inspector who finds a problem makes a recommendation to the Division of Facility Services, which reviews it and sends it to the Penalty Review Committee.

In 1990, county social workers began complaining that Red Wells, then head of the Division of Facility Services, was rejecting or reducing fines after holding private meetings with nursing and rest home operators.

To prevent the unilateral rejection of fines, the state set up an Internal Review Committee composed of several lower-level state regulators. Instead of meeting behind closed doors with the head of Facility Services, homes charged with violations meet with the committee to argue their case.

State and county inspectors are supposed to be notified of the meetings and invited to attend. But county inspectors say the committee has made little effort to inform them of meeting times or accommodate their schedules.

Jesse Goodman, the new head of Facility Services, says the agency is trying harder to include county inspectors. He adds, however, that the main purpose of the meetings is to give the homes their say. The committee “is primarily geared toward the aggrieved party,” says Goodman. “The facility, being the ag grieved party, should have the opportunity to offer additional information.”

Repeat Offenders

It’s that “give-the-industry-a-break” attitude that patient advocates blame for the state’s reluctance to make homes play by the rules. State inspection records are filled with cases where the state has taken little or no action against errant homes:

Earlier this year, social workers in New Hanover County found a bedsore on a Wilmington nursing home resident’s foot that was so infected, it had developed gangrene and become infested with maggots. The man’s foot had to be amputated — but the state declined to fine the home after concluding that staff could not have prevented the infection.

Last December, a patient with Alzheimer’s disease disappeared from a Bynum rest home. The woman was never found — and the home was never fined.

Last year a Hendersonville nursing home resident wandered out of the building, fell into a drainage ditch, and drowned. The state fined the home $250.

In June, three staff members at a Kernersville rest home punished an unruly resident by slapping her, pinching her breasts, swinging her by her arms and legs, and forcing a bar of soap into her mouth. The home — owned by A. Steve Pierce, the largest rest home operator in the state — was fined $500.

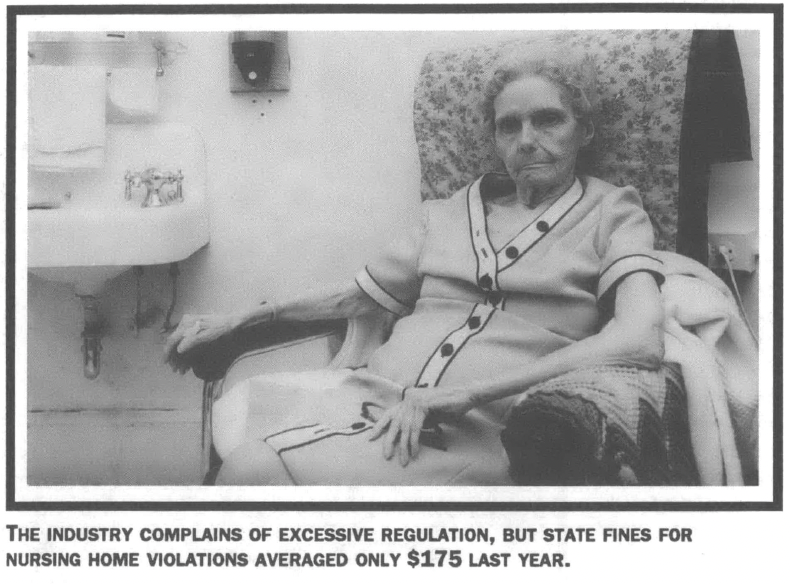

All told, the state levied $67,070 in penalties against nursing homes last year — nearly double the fines assessed in 1988. But according to a review of state records by the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research, the average amount of each fine dropped from $327 per violation in 1988 to $175 last year.

The non-profit center also found that a handful of homes keep breaking the rules. Seven homes accounted for nearly a third of all fines last year — yet the state has revoked the licenses of only two repeat offenders.

The lack of state action puts patients at risk, permitting some homes to repeatedly ignore health and safety standards. Hillhaven-Orange, a Durham nursing home operated by the second-largest chain in the state, was slapped with $6,250 in fines in 1989 — more than any other home in North Carolina. The following year, the home drew another $2,150 in penalties.

Then, in December 1990, an aide at Hillhaven-Orange found maggots in a resident’s vagina. The state fined the home $250. Patient advocates were outraged, but home operators still dispute the fine. “It was never proved what, if any, organisms were found in the resident’s vagina,” says Rita Carter, an administrator with the Hillhaven chain.

“Budgetary Restraints”

Although patient advocates have long focused on reforming nursing homes like Hillhaven, in recent years they have begun to direct more attention to life threatening problems at rest homes.

Long-term care for the elderly in North Carolina is split between 300 nursing homes that provide medical services and 450 rest homes that provide baths, grooming, and other personal care. But the line between the two is blurred. The state, with the industry’s blessing, has kept strict limits on the number of nursing homes. As a result, beds are in short supply, and elderly patients who need nursing home care are ending up in rest homes, which have fewer aides and no staff nurses.

That policy amounted to a death penalty for Helen Jarrell and the two other residents asphyxiated by restraints in rest homes. While federal law strictly limits the use of physical restraints in nursing homes, there is no such rule governing rest homes, which receive no federal funding and are free to use vests and wrist cuffs to tie residents to their beds or wheelchairs.

The deaths prompted Marlene Chasson and other advocates to fight for a rule requiring rest homes to train aides in the use of restraints, but the industry stalled the measure in a rulemaking committee. Chasson then wrote to Governor Jim Martin, asking him to intervene.

Martin sided with the industry. In his response to Chasson earlier this year, the governor said the state was opting for a voluntary training program.

“In these times of budgetary restraints, administrative rules proposals which impose additional costs are not likely to receive favorable review by those directly responsible for fiscal oversight,” he wrote. “It is to be expected that providers resist requirements that impose costs for which they will not be reimbursed.”

But while the state was quietly withdrawing the restraint rule, the rest home industry was busy at the state legislature lobbying for a rate increase. Lawmakers boosted reimbursement to $900 a month for each rest home resident — yet operators still insist they cannot afford staff training.

All this seemed like deja vu to Chasson. Several years ago, she and other advocates went before the state Social Service Commission to argue for a rule requiring rest homes to train their aides.

“We went down there and spent the entire day with them,” she recalls. “I thought we had it.”

And they did have it. The commission recommended training — but when the proposal came before DHR, regulators overturned it. The reason: Training would be too expensive.

Buying Access

What frustrates Chasson most is that the industry and its lobbyists seem to have unlimited access to state lawmakers. “It’s hard to say there is no influence when committee chairs refer to them, ask them questions, and vote the way they want them to vote,” she says.

Pam Silberman, a lobbyist for state legal services who works on health care issues, says political contributions help the industry gain access to legislators. “We don’t have the money — and I think that really makes a difference,” she says. “I don’t mean to imply that all legislators are influenced by these kinds of efforts, but some of them are.”

Campaign contributions and personal contacts help industry lobbyists develop friendships with lawmakers, she adds. “It’s much harder to do something your friend says will impact on his business than to do something for someone you don’t know very well.”

Bill Franklin, chief lobbyist for North Carolina rest homes, thinks advocates like Silberman overestimate the political power of the industry. He says the real obstacle to quality care is that the state doesn’t reimburse rest homes enough to cover the cost of caring for poor residents. Rest homes, Franklin says, cannot afford big campaign contributions — so they focus instead on meeting with legislators who are favorable to the industry.

“The small amount we’ve been able to contribute has not been of great consequence,” he says. “I think our grassroots efforts play a far greater part than any contributions we have made.”

Craig Souza, the chief lobbyist for nursing homes, has no apologies for their big political contributions. “That’s the system,” he says. “We play it fairly and we play it openly. We’re not looking for anybody to do anything but be fair.”

Whether through contributions or contacts, the industry does exert a great deal of pull in the state legislature. “Rest home lobbyists are everywhere,” says one legislative aide who asked not to be identified. According to the aide, lawmakers who tried to question some financial data supplied by an industry lobbyist during a recent request for a rate increase were simply ignored.

Despite such obstacles, advocates for patients and their families say they will keep pressing for reform. “It is stressful when you become aware of the political compromises in the long-term care arena and the enormous power the industry wields,” says Chasson. “You do get burned out — but you just have to keep hammering away at it.”

Tags

Tinker Ready

Tinker Ready covers nursing home issues for the News and Observer in Raleigh, North Carolina. (1992)