This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Two years ago, Jim Lambert checked his father into a nursing home in Mobile, Alabama. It was Valentine’s Day. His father, Prentiss, was 81 years old, and suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. “He was confused and hard to understand,” Lambert says. “My mother kept him at home as long as she could, but she was a little bitty lady, and she couldn’t handle him anymore.”

Prentiss weighed 182 pounds when he checked into Hillhaven Nursing and Convalescent Home. Within three months, he had lost 28 pounds. He slipped in his own urine several times, and aides began keeping him tied up and heavily medicated. He developed bed sores, bruises, a black eye, a urinary tract infection. He fell again and broke his hip, leaving him permanently bedridden.

Lambert, a successful building contractor, complained to the state repeatedly, but Hillhaven was never fined. He tried writing U.S. Senator Richard Shelby. “My father has been grossly abused,” he told the senator. “Hillhaven has violated every statute in both the Federal Register as well as the State Guidelines. Yet, the abuse continues and the state appears to look the other way.”

In May, Prentiss Lambert died. He weighed 94 pounds, his body contracted into a painful fetal position. His son is suing the nursing home for neglect and abuse.

“I don’t need the money,” says Lambert. “I just want to expose this nursing home company and make them clean up their act. My father had nothing to look forward to in that place but death. It was like being in a prisoner-of-war camp.”

Two years before Lambert put his father in Hillhaven, Mary Ropp checked her sister Linda Stewart into a nursing home in Charleston, West Virginia. Linda was 32 years old, and disabled by multiple sclerosis. “She was living with me, but I was having a difficult pregnancy,” Ropp says. “She decided to go into a nursing home.”

Stewart weighed 120 pounds when she checked into Capital City Nursing Home. Within three months she had lost nine pounds. She became dehydrated, her lips cracked and peeling. She developed bedsores, and was hospitalized several times for infections and internal bleeding. Her body contracted painfully.

Ropp, a janitor, complained repeatedly to the state, but Capital City was never fined. She tried writing U.S. Senator Robert Byrd. “We have reason to believe Linda isn’t being fed,” she told him. “Due to recent weight loss. One former employee was eating Linda’s food instead of feeding her.” In April 1991, Stewart died of an infection. She weighed 90 pounds.

“It kinda makes my blood boil,” says Ropp. “I know that what happened to my sister is happening to hundreds, maybe thousands of other people. These nursing homes are not doing their jobs. Everybody that’s abreathin’ deserves to have dignity wherever they are and be taken care of.”

Abuse and Neglect

Mary Ropp and Jim Lambert come from very different places. She grew up in the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia; he lives on the Gulf Coast of Alabama. She worked as a custodian before receiving her certificate as a nurse’s assistant; he runs a large contracting firm that specializes in disaster repair. She sent her senator a simple handwritten note; he mailed his a two-page typed letter and met with him personally.

Yet the two shared a common experience: They both watched a family member die, slowly and painfully, in a place that was supposed to provide comfort and care. And they both ran into a dead end when they asked state and federal officials to help.

The substandard conditions in many Southern nursing homes have been extensively documented in recent years. Across the region, investigations have revealed widespread understaffing, poorly trained staffs, and even physical abuse and rape of nursing home residents:

In Georgia, an investigation by the Atlanta Constitution found residents living in degrading conditions. “Residents were picking cigarette butts off the floor and out of ashtrays and eating them,” the paper reported. “Some residents had experienced weight losses of up to 40 pounds in recent months; some were found tied to beds or to chairs. In bathrooms, inspectors found dried feces smeared over the commodes, floors, and walls.”

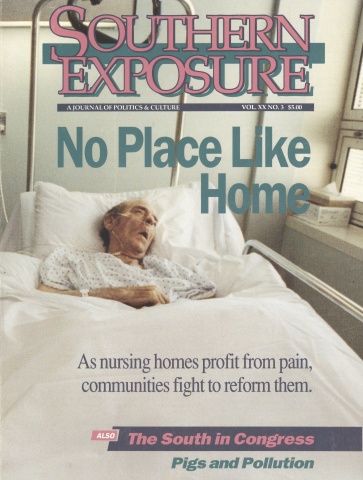

In Texas, a four-month investigation by Nancy Stancill of the Houston Chronicle found widespread abuse and neglect. Eligia Aebersold, who is pictured on the cover of this issue, died eight days after doctors removed his right hip socket to halt a raging infection. His wife Thelma had found him lying in his nursing home bed, green flies buzzing around a urine-soaked bandage that covered a huge, bloody wound.

In Arkansas, an undercover investigation of nursing homes by the state attorney general found “a host of problems including understaffing, improperly trained staff, infestations of mice and roaches, residents left unattended and covered in urine and feces, linen shortages, falsified charts, infectious bedsores, physical abuse and rape.”

In North Carolina, a legislative study committee documented similar conditions. In a single year, more than 1,000 complaints were filed against nursing home operators.

A federal survey of 15,600 nursing homes found 25 percent failed to properly administer drugs and prevent the spread of infection, and 33 percent stored or served food improperly.

Yet despite the long list of such revelations, conditions in nursing homes and other institutions that provide long-term care for the elderly and disabled remain largely unchanged. In every Southern state, grassroots and legislative efforts to reform the industry and provide alternatives have encountered enormous obstacles.

Why? How can abusive and neglectful conditions be documented year after year, and yet be allowed to continue?

To answer that question, Southern Exposure conducted an investigation of the political and economic obstacles to reform. We examined scores of state and federal documents, including administrative complaint reports, penalty review hearings, and state licensing records. We spoke with nursing home operators, employees, and residents, as well as family members, patient advocates, union leaders, and local and state officials.

We discovered that while officials and reporters have done much to document conditions in nursing homes, they have done little to expose the extraordinary power and influence of the industry. Nursing homes make their living from public funds — tax dollars contribute roughly half of all industry revenues. Yet nursing home owners and their paid representatives battle to weaken health and safety standards, evade inspections, and divert money from residents and staff into real estate and investments.

“These nursing home corporations are huge, and they are powerful,” says Suzanne Harang, a registered nurse in Covington, Louisiana who now serves as a national advocate for patients. “The nursing homes say, ‘We do a good job.’ But my feeling is, ‘How do you get such a bad rap if you do such a good job?’ They keep the quality of care down so they can keep their profits up.”

Corporate Empires

With people living longer and families living farther apart, more and more Americans find themselves forced to rely on nursing homes and other institutions for long-term care. This year, the nation will spend a projected $66 billion on nursing homes — up from $43 billion in 1988. Nursing homes now consume eight cents of every dollar spent on health care, making them the third largest segment of the healthcare industry.

Today nearly 1.7 million people live in over 19,000 nursing homes. Some medical experts project that by the year 2030, the number of nursing home residents will reach 5.3 million.

And those figures don’t account for the one million elderly citizens currently living in 41,000 rest homes (also known as board and care homes, group homes, and personal care homes). Such facilities provide less medical care — and are subject to even less government supervision — than nursing homes.

The modern nursing home industry owes its existence to the federal government, which began providing homes with millions of Medicaid and Medicare dollars during the mid-1960s to care for the elderly poor. To convince more homes to accept poor patients, the government placed no ceiling on costs and agreed to reimburse owners for their mortgage interest and property depreciation — a blank check that virtually guaranteed nursing home owners a healthy profit on their investment.

“Our current long-term care system is fundamentally a creature of government policy,” says a report by Catherine Hawes and Charles Phillips of the Research Triangle Institute, a non-profit think tank in Durham, North Carolina. “Nursing home policy [is] a schizophrenic and nearly uncontrollable amalgam of increasing cost, substandard care, and discrimination against both those most in need of care and those least able to pay for such care.”

As the industry boomed and spending on nursing homes soared, large firms began to move in on what had long been a family-run business. For-profit corporations quickly took over 75 percent of the industry and developed subsidiaries to sell their own nursing homes essential and lucrative services such as food, laundry, drugs, management, construction, and real estate investment.

“The dominant trend in the nursing home industry during the 1970s and 1980s,” report Hawes and Phillips, “has been increasing concentration and corporatization of ownership.” Big nursing home chains dramatically expanded their control of the industry — and much of the growth was centered in the South. The Arkansas-based chain of Beverly Enterprises, for example, went from 47 homes in 1971 to 1,136 homes in 1985. The company is now the largest owner of nursing homes in the nation, with 91,000 beds in 34 states.

Beverly and the nine largest nursing chains own 15 percent of all beds nationwide. In Texas, Beverly and ARA Living Centers of Houston control 25 percent of all beds, dominating many rural areas of the state.

The result of such concentrated corporate control has been fewer options for consumers, less autonomy for local nursing home operators, and more economic and political clout for the chains. “Nursing homes used to be mom-and-pop operations,” says Charles Phillips. “Now they’re major real estate ventures and the source of corporate empires.”

Our Money, Their Profits

For their part, nursing home chains and other owners often complain that they cannot afford to improve conditions, saying the government does not give them enough money to care for poor patients who cannot pay the bills. Indeed, care for the elderly — like other human services — has traditionally been a low priority in most Southern states.

The South is home to a disproportionate number of elderly citizens who are poor. According to federal data compiled by Health Care Investment Analysts (HCIA) of Baltimore, the percentage of nursing home residents who receive assistance from Medicaid is higher than the national average in all but two Southern states. Last year federal and state funds from Medicaid helped cover the cost of care for more than 75 percent of nursing home residents in Mississippi, Arkansas, Georgia, and Kentucky.

Under the Medicaid program, each state decides how much it wants to reimburse nursing homes to care for the elderly poor, and the federal government then matches that commitment. But despite the enormous need in the region, Southern states rank among the stingiest when it comes to contributing their share to nursing home care. According to 1989 data from the federal Health Care Finance Administration, every state in the region provided Medicaid payments below the national median of $70.06 a day. Arkansas ranked last in the nation with a daily reimbursement rate of only $34.89 per patient, followed by Louisiana at $42.62.

“The differences from region to region are incredible,” says David George, who has operated nursing homes in Georgia, North Carolina, and Colorado. “You’re dealing with the same elderly people who have the same needs — but in some states you get twice as much money and twice as much care.”

The low reimbursement rates make it tough to provide decent care. “When I got down to Georgia, it was just a completely bare bones budget,” says George. “It’s pretty incredible that anybody can do anything with the amount of money they get here. You barely have enough to get a person up and cleaned and fed in the morning before the family comes in, so they don’t find the patient lying in a puddle of urine.”

The nursing home industry has sued several states to raise Medicaid rates. In Texas, rates have climbed 17 percent since 1990. But analysts predict most financially strapped states in the region will continue to shortchange the poor when it comes to nursing home care. “If the money is not there in state budgets, it’s not there,” says George Pillari, president of HCIA.

But while rates remain low, rules governing how public Medicaid funds are spent generally favor nursing home owners at the expense of patients and workers. “Owners go to legislative committee meetings and testify up and down about how regulations will adversely affect patients,” says David George. “But what they’re really talking about is how their profit margin will be eroded away.”

Profit margins for the industry remain high, even with low reimbursement rates in the South. A review of data supplied by HCIA shows that four Southern states — Texas, Arkansas, Virginia, and Louisiana — enjoyed the highest profit margin in the nation in 1990. Last year, Beverly Enterprises of Arkansas reported pretax profits of $42.6 million, more than double the previous year.

“Rising stock prices and improving financial performance suggest the nursing home industry will flourish over the next few years,” reports the industry journal Modern Healthcare.

One reason: Reimbursement rules allow nursing homes to skimp on patient care and staff wages while they funnel public money into subsidiary companies that deal in equipment, management, pharmaceuticals, building expenses, and real estate investments. In essence, nursing homes function as a sort of front operation — enabling private owners to take billions of dollars from taxpayers and invest them in their own businesses.

“Here states are absolutely scraped to the bone on public funds, and yet you have nursing home owners who are raking in hundreds of thousands of dollars playing real estate games with Medicaid dollars,” says Barbara Frank, associate director of the National Citizens’ Coalition for Nursing Home Reform. “A nursing home corporation pays a subsidiary corporation to manage a home, and then shows a loss. In reality, they just paid themselves a huge chunk of money to run their own home.”

Workers and Patients

Nursing home workers pay the price for high profits — especially in the South. The region is home to seven of the 10 states that offer the lowest salaries and benefits per patient. Homes in Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas spent less than $15,000 on staff costs per patient in 1990.

“Nursing home aides work long, hard hours for low pay,” says Barbara Frank. “The aides are the ones who have to deal with the unmanageable situations — and that makes it harder on patients” (see “Back-Breaking Care”).

States also make it harder on patients by limiting the number of beds in nursing homes certified to receive Medicaid funds. The policy creates long waiting lists for beds — guaranteeing homes a steady supply of customers and allowing them to discriminate against those most in need of care. Many homes refuse to accept elderly citizens who require extensive and expensive care, preferring to fill their beds with more profitable patients. They also discriminate against black patients. According to a nationwide survey conducted by patient advocates in Tennessee, blacks comprise 29 percent of those eligible for Medicaid, yet they receive only nine percent of the Medicaid dollars spent for skilled nursing home care.

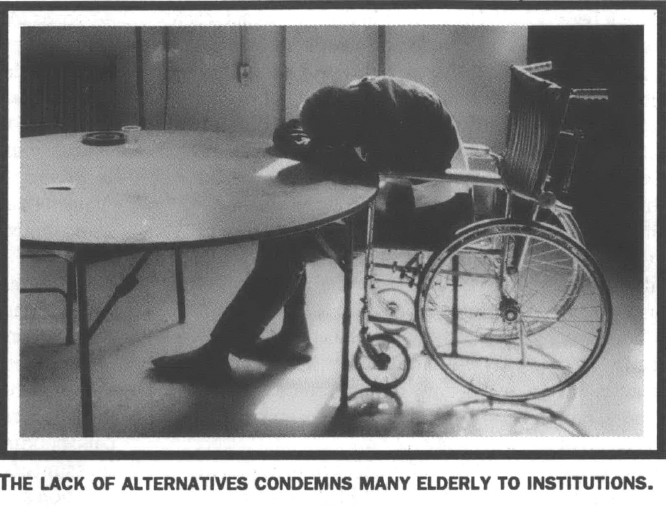

Elderly patients who need medical care have few other places to go. The nursing home industry lobbies states to devote public funds exclusively to nursing homes, undercutting competition from home health care and other alternatives. Fewer than 20 cents of every dollar spent on long-term care currently goes to care for the elderly in their own homes. Eight states, including six in the South, provide no funding for residents of rest homes (see “Where the Heart Is”).

The lack of alternatives condemns many older citizens to spending their final years in an institution. Even nursing homes that provide good medical care tend to be sterile and depressing places that isolate residents from their homes and communities. Doctors in some of the cleanest and most comfortable homes in the region report that the loneliness and impersonal environment of institutional care have driven some patients to kill themselves, and have prompted many more to look forward to death.

“State reimbursement policies create powerful incentives that are almost entirely perverse,” says Gordon Bonnyman, an attorney who has fought to reform nursing homes in Tennessee. “Development of long-term care has been shaped tremendously by Medicaid policy, which pays for institutional care but not for home care or other alternatives.”

Blocking Reform

Outraged by the increasing power of the industry and the decreasing standard of care, advocates for patients and their families have pushed for tougher federal regulation of nursing homes. In 1987 they won an important victory when Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Known as OBRA, the new law requires nursing homes to draft a plan of care for each resident, provide 24-hour nursing services, employ trained nurse’s aides, and pay stiffer fines for violations of health and safety standards.

“I’m just holding my breath and waiting to see how much of an effect OBRA has,” says Becky Kurtz, coordinator of the Senior Citizens Advocacy Program in Atlanta. “I’m optimistic that it will — if our states take it seriously and enforce it.”

So far, though, states have had no opportunity to test the reforms. After OBRA was passed, the nursing home industry lobbied hard to weaken and delay the federal regulations needed to carry out the law. The industry trade association hired Deborah Steelman, a former Bush administration advisor, to lobby the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). As a result, the administration did not announce the new rules until last August — five years after the reforms became law.

“They are an extremely strong lobby with a lot of money behind them,” says Jody Hoffman, a health policy specialist with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). “These people have the money to purchase a former administration official with ties to OMB, which is where they needed to go to stop the regulations. For groups who don’t have that kind of access — consumers, workers — it’s a very frustrating process. Their side is not heard.” Indeed, the nursing home industry remains plagued by high costs, poor care, and lax regulatory enforcement. To understand the full extent of the trouble, it is essential to look beyond the cases of abuse and neglect that have captured headlines and examine how the industry has used its political and economic position to systematically block reforms.

Southern states have traditionally taken a “hands off’ approach to regulating business. Across the region, political leaders of both parties are accustomed to defending low wages, dangerous working conditions, and generous subsidies and tax breaks for business. As a result, they often construe nursing home regulation, in the words of one Georgia state legislator, as “an infringement of private enterprise.”

The nursing home industry does its part to make sure it stays that way, pressuring state lawmakers to increase public spending for nursing homes and to block regulatory reforms. Across the South, patient advocates and state inspectors struggling to improve nursing home care have met with strong opposition from the industry, its lobbyists, and elected officials who own nursing homes or accept campaign contributions from the industry (see “Resting Uneasy”).

“It’s like every other business,” says David George, who quit his job as a nursing home administrator after uncovering Medicaid fraud in North Carolina. “Nursing home owners are in there lobbying and pitching to make sure their interests are taken care of.”

The lobbying and campaign contributions pay off. Consider the case of Georgia, where patient advocates and fire officials teamed up last year to support a bill mandating sprinkler systems in all nursing homes. The year before, a fire in a Virginia nursing home without sprinklers had killed nine patients and hospitalized 100. Nevertheless, nursing home owners in Georgia fought the measure, saying they could not afford added fire protection.

“We have hit a brick wall of opposition from the lobbyists for nursing homes,” said Lieutenant Governor Pierre Howard, who fought for the sprinkler bill. “I can imagine no greater horror than sitting in a wheelchair or lying in bed while smoke fills the room.”

Nursing home owners had tried to get rid of Howard, contributing more than $30,000 to his opponent in the 1990 Democratic runoff. The political action committee of the Georgia Health Care Association also reported $29,425 in contributions to political candidates that year — making the industry the 15th biggest contributor among 300 lobbying groups in the state.

What’s more, several state lawmakers had personal ties to the nursing home industry. Senate Majority Leader Thomas Allgood and his family owned an interest in four nursing homes. State Representative Troy Athon was a former lobbyist for the Georgia Health Care Association, and his wife served as president.

In addition, Representative Peg Blitch owned a 95-bed nursing home, and Representative George Green practiced as a physician in several homes. Both served on the House Human Relations and Aging Committee — which stalled the sprinkler bill, and then amended it to force taxpayers to foot the bill for installation up front. Even with full public funding, the measure was eventually killed.

Closer Inspection

Just as the industry uses its economic clout and political influence to block reforms at the legislative level, owners and operators also work to stall or weaken enforcement efforts by state regulatory agencies.

“The industry also has a great deal of influence at the administrative level where the laws are enforced,” says Becky Kurtz of the Senior Center Advocacy Program in Atlanta. “They have the resources to keep up with everything that’s going on. When the budget is being considered, for example, they get in there early with department staff, saying, ‘Here’s what we need and here’s why.’ They keep up constant communication.”

The communication helps convince regulators to follow the “hands off’ approach adopted by legislators. State officials in the South have been reluctant to penalize nursing homes, even in cases of widespread, repeated abuse. In 1982, Georgia empowered officials to assess daily fines on nursing homes for repeated violations — but regulators did not use the law for seven years, even though there were hundreds of repeat offenders.

“The regulatory agencies are hamstrung,” explains Charles Phillips of the Research Triangle Institute. “Nursing home beds are in short supply, so what do you do when there’s a violation? Historically the only option has been to decertify the facility and cut off their Medicaid funds. But then what do you do with the residents? They’ve got to go somewhere.”

As a result, even reforms that make it past legislators seldom get enforced. “I think the process we have in place now for inspections is good,” says former nursing home administrator David George. “But there’s always a lot of behind-the-scenes political things that go on to try to curtail the number of inspectors. It’s a question of having the resources to do the job.”

Other Voices

While the industry has the resources and connections to make its opinions known, the elderly and their advocates must struggle to be heard. Independent ombudsmen and patient advocates remain understaffed and underfunded, limiting their ability to press for reforms.

Each state is required to maintain an independent ombudsman who can educate nursing home patients and their families about their rights and help them resolve problems. Many ombudsman offices, however, receive little money to do their job.

Renee Johnston serves as ombudsman in Nashville, Tennessee. She is responsible for serving 9,259 elderly patients in 167 facilities. Her budget for the coming fiscal year is $49,000 — barely enough to cover her salary and travel expenses.

“What we try to do to offset the large volume of residents who need help is recruit community volunteers,” says Johnston. “We’re trying to place one volunteer in every facility. Right now I have 15 volunteers — so you can see I need a lot more.”

With little money spent on public education, many nursing home residents remain unaware of their rights. “I’m constantly amazed by how few people know about the ombudsmen and advocates that are there for patients and their families,” says Atlanta advocate Becky Kurtz. “People live in fear in nursing homes. They’re afraid if they speak up about problems, there will be repercussions — and they’re often right. They need to know they can call us for help.”

Kurtz and other advocates agree that meaningful reform will take a concerted effort on the part of patients, families, workers, and state and federal officials. They cite a variety of measures needed to improve nursing home care:

reform Medicaid reimbursement rules to direct more money to patient care and employee wages. monitor enforcement in each state to ensure that top officials don’t lower or delete fines for problem homes.

use state and federal provisions to take over homes that repeatedly violate health and safety and standards.

establish independent committees with wide community representation to watchdog nursing homes at the local level.

organize families to visit homes and keep a closer eye on conditions.

provide better funding for ombudsman and advocacy programs that protect the elderly, and for community-based alternatives to nursing homes.

In the end, the quality of care in nursing homes hinges on whether the public organizes to counter the influence of the industry. “The community has to get involved for the industry to change,” says Renee Johnston, the Nashville ombudsman. “People have to advocate that conditions for staff members and patients be improved. We need more public awareness and public pressure. We need action on the part of family members.”

Those who have watched a family member die from poor nursing home care agree. “We have to start raising hell,” says Jim Lambert, whose father died two years ago. “If these nursing homes can’t treat people right, we need to shut them down.”

“I think it’s a federal crime when a nursing home can do these things and get away with it,” adds Mary Ropp. After she watched her sister mistreated in a West Virginia nursing home, she studied to be a nursing home aide. Now she and her husband dream of starting a non-profit home to care for the elderly.

“Those federal dollars that go into nursing homes are our dollars, our taxpaying dollars,” she says. “When nursing homes don’t do their job, they shouldn’t get any more of our money. Federal laws and state laws should be so strict and so strong that the residents who live in these places get the care they deserve — and they deserve the very best.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.