North River, N.C. — By the broad saltmarshes of Carteret County, Elbert Murray has operated a tiny hog slaughterhouse for more than 30 years. When he started his business, most local farmers raised at least a few hogs. Rich or poor, white or black, they had a muddy pigpen and a slop trowel, and a smokehouse to preserve the meat through the winter. Every autumn Murray would butcher 25 or 30 hogs a day for his neighbors, seven days a week.

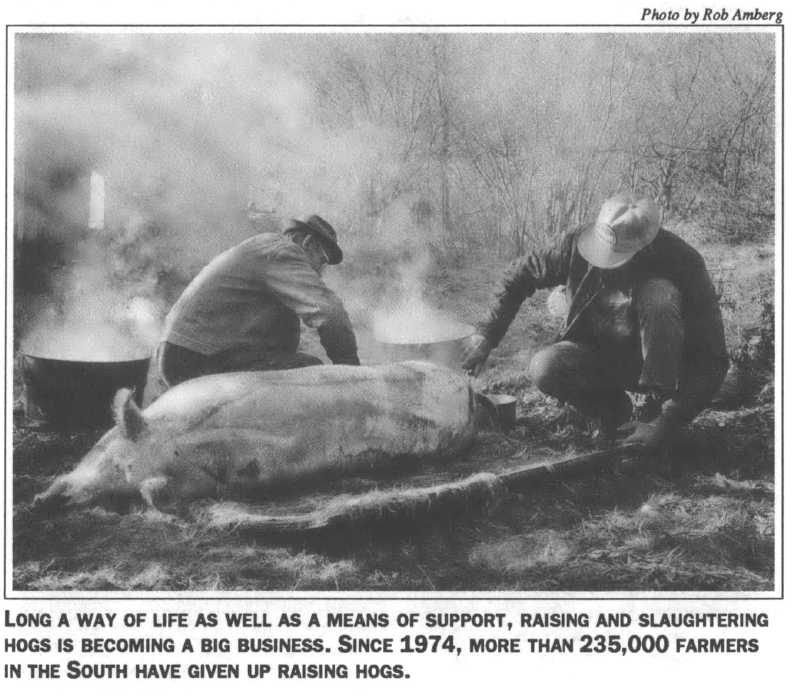

Hog farming was a way of life then. Cured hams, sausages, bacon, chitlins and hog jowls, sidemeat and fatback — they staved off hunger during hard winters and held together many a family farm. Pork flavored local cuisine more extensively than any other food. And the passion for pork — in North River and throughout the South — elevated raising, killing, preserving, and cooking hogs to a high art and a community ritual.

But things are changing. Nowadays Murray’s clapboard slaughterhouse seems as old-fashioned as a mule-driven plow. Dwarfed by corporate superfarms that breed and fatten as many as 40,000 pigs at a time, fewer small and part-time farmers can afford to raise hogs, and the 73-year-old Murray now butchers and dresses more deer for sportsmen than pigs for farmers. Only a few of the better-off local farmers still raise hogs for market, and they ship them to a processing factory owned by agribusiness conglomerates in Kinston and Wilson, more than 70 miles away. North River doesn’t get the jobs, the pork, or the profits.

A weary Murray feels like the world has passed him by. He and the few people who still bring him hogs belong to vanishing communities that can’t compete with corporate agriculture. The young people in North River are moving away to find jobs. His slaughterhouse barely breaks even, and he spends most of his income on medical bills.

“I’ve worked myself to death,” says Murray, a wiry black man considered one of the elders of the community. “They make it nearly impossible to live for yourself now.”

Murray and his neighbors in North River are not the only ones threatened by the rapid growth of corporate hog farms. The transformation of hog farming from a small, local enterprise to a huge, multi-million-dollar industry endangers the future of family farming, the economic health of rural communities, and the safety of drinking water across the South.

Hog production has long been the domain of men like Murray and independent, family farmers. Over the past decade, however, the pork business has begun to follow the path of the poultry industry. Thirty years ago, a million family farms had chicken coops, raising birds to eat at home and sell at the market. Led by Frank Perdue and other chicken kings, the poultry industry is now dominated by a few multinational companies that control every stage of production from egg to dinner table. They raise the birds by the tens of thousands in high-tech confinement sheds, and the old coops stand empty and dilapidated in antiquated yards (see “Ruling the Roost,” SE Vol. XVII, No. 2).

Now many of the largest poultry firms — including Tyson Foods, ConAgra, and Cargill — are turning their attention to the hog industry. Refining the lessons of the poultry boom, they hope to extend their system of “vertical integration” to the pork business, dominating the production process from grain mill to hog farm, from slaughterhouse to supermarket.

The rise of corporate hog farming means bigger farms — and fewer farmers. The size of the average hog farm in the South has almost quadrupled since 1974, from 29 pigs to 111 last year. Over that same period, three-fourths of all hog farmers in the region — more than 235,000 farmers — have been driven out of business.

What’s more, say most observers, the devastation of family hog farms is accelerating. The only substantial growth in the industry is among operators with more than 1,000 hogs, who now produce at least three of every four hogs raised nationwide. At this rate, predicts Steve Marbery, editor of Hog Farm Management, the “family hog farm will become extinct early next century.”

Factory Farms

Corporate hog farming spread first and fastest in North Carolina. Since 1974, the number of farms in the state raising fewer than 50 hogs has plunged from 17,000 to fewer than 4,000. The number of operations raising more than 500 hogs has meanwhile soared from 20 to nearly 200, giving North Carolina the largest and most concentrated hog industry in the region.

Nowhere is the trend to corporate farming clearer than in the small town of Rose Hill, home of Murphy Farms — reputedly the largest hog producing operation in the world. Standing in the elegant corporate headquarters on the edge of town, it’s hard to imagine its occupants have anything to do with raising hogs. Well-tailored executives and accountants move efficiently about a building adorned with green marble floors and plush pigskin chairs. Outside, a company helicopter awaits its next flight.

A sophisticated telecomputer system links these modern-day pig rearers to more than 600 contract farmers — some as far away as Iowa — who raise a total of more than 1.5 million hogs a year for Murphy Farms. Although Murphy raises hogs on its own land, it relies on this extensive network of growers for most of its meat.

The contracts with hog farmers resemble those that now dominate the poultry industry. Growers must supply the land, build their own hog houses, and shoulder all of the labor and financial risks. The company supplies them with piglets and feed, and returns to take the animals away when they are grown.

The operations are huge — and expensive. Bred with new genetic technology to grow leaner and faster, thousands of hogs are crowded into concrete cubicles in $100,000 confinement sheds. To take advantage of specialized equipment, the pigs are bred, raised, and fattened for slaughter at different sites. Automated sprinklers and fans cool the animals. Electronic feed systems deliver a scientific diet, including vitamins and synthetic hormones, that fatten them to 260 pounds in only six months. When the hogs go to the packing plant, ultrasound machines like the advanced diagnostic tools used in hospitals are increasingly used to measure their leanness.

“Swine management supposedly started in the Midwest,” says Sam Ennis, a Murphy production manager. “But we feel like and hope that we’ve taken it to a different tier, a different level, and maybe have commercialized it a little bit more.”

The factory-like farms are transforming the culture of hog farming. Some contract growers who work for Murphy grew up around pigs and are adapting to corporate farming as best they can. More and more, however, the new breed of corporate hog farmers are businessmen eager to move up the corporate ladder. They are more at home driving a BMW than a tractor, more comfortable carrying golf clubs than slop buckets. For these men, raising hogs is just another financial investment. They hire laborers to work with the hogs, and dutifully follow instructions issued by Murphy Farms.

“I’ve just been a business person all my life,” said Steve Draughon, a grower with Murphy Farms who had never raised hogs before he invested more than $900,000 in a contract operation. “The size of these facilities now, and the income they generate, and the management expertise that it takes to run them is more suited for somebody that’s good at managing a business.”

Family Exodus

Mathew Grant has never seen himself as a business person. A family farmer in Tillery, a rural black community on the Virginia border, Grant has raised hogs since 1957. Though he never owned more than 20 sows, the animals helped him to be self-sufficient, educate his children, and — in a county with a tremendous rate of black land loss — hold on to his family farm.

Grant can recall a day when every black family in Tillery raised hogs. One by one, his neighbors closed their farms and lost their land. Grant held on. He was the last hog farmer in town — perhaps the last black hog farmer in the county.

Then, last winter, Grant finally gave it up. He simply could not compete, he says, with the growing number of corporate farms raising 500 sows. Most of the big farms are owned or supplied by Smithfield Foods, a pork processing giant based in Virginia. And if Smithfield doesn’t give you a contract to raise hogs, Grant says, it’s almost impossible to survive.

Pork Barrel Politics

Murphy has also used his power in the legislature to funnel public money to North Carolina State — his alma mater— which supplies the hog industry with valuable research and technical assistance. Last year he introduced a bill criminalizing interference with animal research at the university, and pushed lawmakers to spend $3.3 million improving roads for a university stadium.

The animal research program at NCSU has also been supportive of Murphy. Many graduates and staff members from the school have gone to work for Murphy, and agricultural extension employees from NCSU have traveled from county to county to speak in support of large-scale operations like Murphy's.

These state-employed specialists have taken advantage of the revolving door, moving from the Murphy-supported NCSU program into plush offices in Murphy’s headquarters in Rose Hill. Terry Coffey, for example, who used to be a swine specialist with the NC Agricultural Extension Service at NCSU, was recently named director of research and development at Murphy Farms. Public affairs director Lois Britt headed the agricultural extension office in Duplin County before signing on with Murphy.

Public affairs have been much on Murphy’s mind of late. Last February, the state senator announced his retirement from public office—just two and a half weeks before the Kinston Free Press reported that Murphy had been questioned by state agents as part of an investigation of “alleged irregularities" in the campaign finances of former state senator Harold Hardison.

Citizens who live near Murphy Farms are also questioning how Murphy does business, saying his operations foul the air, contaminate the water, and drive small farmers out of business.

Murphy turned down repeated requests for an interview. “He’s leery of reporters,” explains Sam Ennis, his area production manager. “I’m sure he feels to a much lesser extent what Ross Perot probably felt. Perot probably felt he was being honest and open and now he’s getting hammered. Murphy has a sense of what will work and he wants to do the right thing. That’s why he can’t understand these environmentalists."

To improve his image, Murphy is using hog waste to create fertile ground for nature preserves and artificial wetlands. But citizens who live near his operations remain unsatisfied, and many say they will be glad to see him retire this year. Says one Bladen County resident: “Do we really want any person in North Carolina to be in a position to exercise this much power and influence in support of his own financial self-interest?" — M.L.K

“Smithfield gets all the hogs he wants, says Grant. “You’re at his mercy.”

Grant is one of the thousands of casualties of the bigger-is-better trend in hog farming — and by all indications, the pressure on small farmers is getting worse. Industry experts agree that in the near future, a family hog farm will have to be able to raise at least 300 sows to survive. That would eliminate nine out of ten of the remaining hog operations in North Carolina by the year 2000. By then, many sources predict, the standard size for contract farms will be 10,000 hogs — and for corporate-owned farms as high as 60,000 hogs.

Few small producers have either the land or money required to operate on that kind of scale. Nor do companies like Murphy Farms have any incentive to provide management, transportation, or technological support to small farmers like Mathew Grant. The corporate farming operations want a uniform, economical product — and that means contracting with fewer farmers who raise more hogs.

Alan Barkema, an agribusiness economist at the First Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, predicts “a substantial exodus” of small farmers who cannot compete with rising agribusinesses. Indeed, many independent farmers, who often have to wait a week in line at packing houses that give priority to larger customers, foresee the day when they just won’t be welcome at all. Unless they have a contract with one of the big producers, they will receive fewer bids for their hogs, will have fewer places to deliver them, and, in many cases, will have to sell to a local monopoly that can set prices without competition.

“It would be tough to go independent,” acknowledges Steve Draughon, the Murphy Farms contractor. Corporate farms are “going to get a premium for their hogs because they can guarantee a constant supply.”

Even the status of farmers like Draughon who contract with corporate firms is uncertain. William Heffeman, chair of rural sociology at the University of Missouri, cautions that producers may enjoy high prices and long-term contracts only during the current period of fast expansion. Once the competition narrows and a handful of firms dominates the industry, says Heffeman, farmers will find themselves forced to accept lower prices and less freedom.

“Branch Plant” Towns

As corporate hog farming shuts down small farms, it also threatens the economic health of rural communities. Even many agribusiness economists and bankers predict that the shifting control of the hog industry will hurt the majority of the rural South. According to bank economist Alan Barkema, the growing exodus of family farmers could overwhelm counties and states with demands for welfare, job training, and other social services.

Many small towns are already finding their economies eroded, as hog production concentrates near a few larger towns that have giant slaughterhouses with networks of contract and corporate-owned farms radiating out into their hinterlands. “Small towns have been hurt both in regions that have gained production and those that lost it,” concludes a recent study conducted by one bank.

The outlook in larger rural towns “may also be less than expected,” cautions Barkema. The companies fighting to control the hog industry plan to obtain their credit and agricultural supplies from other multinational corporations, or from their own agricultural subdivisions based in Dallas, Omaha, or Chicago. According to Barkema, Southern communities will increasingly resemble “branch plant” towns, which have little control over their own economic destiny.

Reducing rural towns to profitable corporate outposts is precisely what the hog industry has in mind. Business leaders and trade publications make clear that the push to take over hog farming is part of a broader plan to extend corporate control of the industry to every stage of the production process. That means pursuing the model of “vertical integration” imposed on the poultry industry — enabling a single company to produce hog feed, raise pigs, slaughter and package the animals, and ship them to market.

Many corporate hog firms have already developed direct ties to slaughterhouses. Smithfield Foods, the Virginia packing firm, merged three years ago with Carroll’s Foods, a large hog farming operation. Smithfield obtains half of its hogs through contracts via Murphy Farms and Carroll’s Foods, and the company is building a large processing plant in North Carolina and contracting with more farmers to supply the new facility.

As the competition to control the hog industry heats up, slaughtering companies are undergoing a dizzying round of mergers, acquisitions, and bankruptcies. Only a few years ago, thousands of small, local outfits slaughtered and processed hogs. Since 1980, however, almost 200 major packing houses have closed down. Ten firms now slaughter nearly 75 percent of all hogs sold nationwide, and most industry insiders expect the field to narrow to three or four companies by the year 2000.

“The hog packing industry is going through more than just a shakeout,” reports the agribusiness weekly Feedstuffs. “It’s closer to an earthquake.”

The biggest tremors are shaking communities in the rural South. Although Iowa still produces 25 percent of all hogs nationwide, the industry is steadily marching below the Mason-Dixon line to escape tough, anti-corporate farming laws in the Midwest. IBP, an agribusiness conglomerate owned by Occidental Petroleum, recently expressed interest in moving its pork business to North Carolina. Such corporate “runaways” want to replace their unionized pork processing plants in the Midwest with larger, more automated, non-union factories in the South.

Brown Lagoons

Rural communities face more than an economic threat from corporate hog farming. As many towns across the region are learning, big farms pose a lethal threat to the environment — fouling the air, polluting the land and water, and creating a waste nightmare for the rural South.

Small farmers have long used hog manure to fertilize their row crops, a system of recycling that was safe and economical. But corporate farms crowd thousands of hogs into confinement sheds on a single site, often generating more manure than they are able to absorb.

More hogs mean more environmental hazards. “The potential for catastrophic problems is greater for 1,000 sows than for 100 sows,” notes Jim Barker, a swine specialist at North Carolina State.

Hog waste contains more concentrated organic matter than human waste, including nitrates, copper, antibiotics, and other nutrients and chemicals harmful to humans in large doses. To treat and dispose of the waste properly, however, is beyond the capacity of most small communities. According to Dr. Leon Chesnin, professor emeritus of waste management at the University of Nebraska, a single operation with 10,000 hogs requires the same amount of waste treatment as a city of 17,000 people.

All told, the waste produced by the eight million hogs raised in the South each year requires as much treatment as the waste of 15 million people — more than the populations of Virginia, North Carolina, and Arkansas combined.

But instead of treating the hog waste, most large companies simply flush the manure into holding tanks, dump it into open lagoons, and spray it on the fields as fertilizer. Many waste lagoons are 30 feet deep — the same depth as neighboring wells.

“Huge corporate hog farms have allowed waste to overflow into nearby water supplies, allowed waste to pollute nearby wells,” says Gary Grant, the son of hog farmer Mathew Grant in Halifax County.

At one operation contracted to Murphy Farms, pipes funnel hundreds of gallons of brown waste brimming with hog feces and urine into stagnant lagoons the size of small lakes. Sprayers that resemble tall lawn sprinklers spew the waste over nearby fields. The odors emanating from such massive quantities of hog manure can be overpowering, and studies indicate that the smell may be making residents and workers seriously ill (see sidebar).

Such dumping can also pollute drinking water. A year-long study of drinking water near swine operations in 18 states, for example, revealed that more than 13 percent had nitrate levels exceeding federal standards. Nitrates can leach into well water and cause infant deaths from a disorder known as “blue-baby syndrome.”

Becky Bass lives a few hundred feet from a large hog farm near Wilson, North Carolina. A mother of two, Bass had to install a new water system because her five-year-old son vomited from drinking well water after Cargill built its hog operation behind their home.

“This water has been good for ages,” says Bass, a young woman who is active in a local citizens group fighting to clean up corporate farms. “Now we’re very concerned about our water.”

Some of the problems stem from dumping too much waste on too little land. “What you’re going to do is overload the soil and it’s going to go down to the groundwater,” warns Dr. Chesnin. “If you have sandy soils or if you have the groundwater close to the surface like southeastern Virginia, or south-central Georgia, or places in North Carolina, it’s a hazard.”

Yet even when corporate farms have plenty of land, they still pollute the land and water. In May 1989, Virginia inspectors found hog waste piled so high at one swine shed owned by Smithfield-Carroll’s that fans designed to ventilate the shed were spraying manure outdoors up to three inches deep. That same month, inspectors also discovered that 1,200 gallons of hog waste had shattered a lagoon wall at another hog operation and flowed into nearby woods.

Such pollution is commonplace. Virginia inspectors have cited Smithfield-Carroll’s for hundreds of violations since the late 1970s. In 1989, the company was fined $15,000 for spraying waste on fields before a rainstorm and for allowing a broken pipe to spill an unknown quantity of hog manure. Other companies have similarly dismal records. In 1986, Virginia inspectors fined Gwaltney of Smithfield $1.2 million for violating its anti-pollution permit at least 237 times. The fine was later reduced, and the company is appealing the citation.

Murphy Farms has also been cited for numerous violations. Last year North Carolina inspectors cited three company operations for lagoon overflows, plugged waste pipes, and a broken flushing system. The firm’s McLaurin operation has been fined more than $2,000 for 25 assessments in the last year.

Environmental Carpetbaggers

Among the remote pine barrens and Carolina bays of Bladen County, Evelyn Willis started a citizens’ revolt to counter the health risks posed by huge hog operations. Two years ago, the 62-year-old, retired insurance clerk learned that Smithfield Foods was planning to build a tremendous hog slaughterhouse near her Elizabethtown community on the banks of the Cape Fear River. She also learned that the plant would attract corporate hog farms that posed a serious threat to community health.

At first Willis underestimated the power of the corporate hog firms. “I used to believe that the state would never allow anything to endanger our environment,” she told a friend. “Boy, was I wrong!” Then Willis contacted the North Carolina Coastal Federation, and the environmental group sent her some information about water-quality regulations.

“The rest, as they say, is history,” recalls Neil Armingeon, a scientist who worked with Willis at the Coastal Federation. “Overnight, she changed from a retiree to an activist. Evelyn, who had never questioned authority in her life, began to understand the dynamics of power and pollution.”

Willis and her neighbors organized, petitioned elected officials, spoke out at public hearings, recruited supporters throughout the state, and filed a lawsuit against the company. It was slow, hard work, and Willis paid a high price for her commitment. “Lifelong friends and neighbors shunned her,” says Armingeon. “She was ridiculed and threatened in her own community.”

Smithfield Foods intends to open its new plant this fall. But before Willis died of a heart attack last May, she and other Bladen County residents managed to pressure the state to develop new regulations designed to protect water supplies from hog farms and other livestock operations.

Willis and her neighbors also managed to spark concern across the state. Four citizens groups and thousands of rural residents in at least 14 counties are meeting regularly, sharing information about corporate hog farms and how to challenge them.

One of the central groups leading the coalition is Halifax Environmental Loss Prevention (HELP), an organization of mostly black residents in Tillery, North Carolina. Members of the group see the surge in corporate hog farming as part of a larger trend in which business singles out poor, rural communities — often black or Native American — for industries that pose dangers to public health. In majority black Northampton County, for example, local citizens have been fighting a proposed toxic waste incinerator as well as several 10,000-hog farms belonging to Smithfield Foods.

“When these corporations want to do something that will cause a stink, they come to our communities,” says Gary Grant, the co-chair of HELP. “We do not have the vocal power or, oftentimes, the voting power.”

To counter the divide-and-conquer strategy of corporate farms, HELP is crossing racial lines to unite black and white residents. Grant, the son of the last black hog farmer in Tillery, frequently meets with Charles Tillery, a white salesman and the great-great-grandson of the town founder, to discuss the dangers posed by hog pollution.

White residents like Tillery are alarmed by the threat to their land. “This is the biggest invasion since the Civil War,” says Tillery. “What we have coming in here are carpetbaggers — environmental carpetbaggers — bringing their operations here because other states have regulations to protect their citizens.”

On May 23, Tillery and Grant joined dozens of other black and white residents in a protest rally at the First Baptist Church in Halifax County. “Trust Me — Hogs Stink,” read one sign. “Ban Factory Farms,” demanded another.

Residents were just as outspoken in voicing their demands. “Whether it’s workers in a factory being exposed to hazardous chemicals or residents in a community being exposed to animal waste, it’s all the same thing,” said Joan Sharp, a member of Black Workers for Justice. “It creates health problems for the individual — and it creates health problems for us all.”

Grassroots Alternatives

Citizens and farmers in North Carolina are also beginning to join forces with family farmers from the Midwest who are alarmed by the Southern migration of hog farming. Prairie Fire, a group based in Iowa, is organizing a conference of groups from 13 states this fall to discuss how to hold corporate hog farming accountable to community needs.

Although the movement has yet to develop a clear agenda, family farmers and residents in many states have pursued a variety of goals:

Enforce existing anti-trust laws. Several federal acts empower officials to prevent large corporations from dominating the hog industry. So far, though, the government has done little to make big companies obey the law.

Extend restrictions on corporate farming to Southern states. Laws in the Midwest and High Plains limit corporate ownership of farm land and forbid pork processors from running their own hog farms or contracting with hog farmers.

Give counties the power to regulate big hog operations. Many local officials would like to treat corporate hog farms like any other big business, but most states currently classify such livestock operations as family farms, exempting them from local zoning. Local residents thus have no power to limit the size of hog farms or keep them away from homes, schools, and churches.

Monitor water and soil pollution. In southside Virginia, a grassroots coalition called PRIDE has pushed the state to pass rules requiring permits for operations with more than 2,500 hogs. Such operations must now have enough capacity to safely store waste for two months and must carefully track how the waste contaminates nearby land and water.

The hog industry dismisses such proposals as the dying gasps of a vanishing generation of backward farmers. The family farmer should simply “end his resistance to corporate farming,” insists Bill Helming, an agricultural economist. “Opposition to corporate agriculture is short-sighted and unrealistic. Resisting — via legislation or other ways — would be foolish and self-defeating.”

If farmers and citizens resist corporate farming, Helming and agribusiness leaders say, hog companies will simply move their operations to more cooperative communities — leaving local hog farmers without grain mills, slaughter houses, or access to credit.

Small farmers know the threat is not an idle one, yet many continue to work with citizens groups to develop an alternative vision of agriculture that includes them and their communities. They envision a system of agriculture that places community need over corporate greed, a system that cares for the land instead of exploiting it.

Gary Grant watched his father raise hogs for more than half a century before corporate farms drove the family out of the pig business last year. He knows that the economic and environmental health of rural Southern communities will be shaped in large part by the growing struggle in the hog industry between large corporations and independent, family farmers.

Corporate Farms Stink

Barnyards and hog pens have long been a fixture of the rural South, and countryfolk are accustomed to living with unpleasant odors. But the corporate hog farms spreading across the region are different.

"Every family had hogs when I was growing up," recalls Gary Grant, the son of a pig farmer in rural Halifax County, North Carolina. “But we weren’t talking about 40,000 hogs on one site.”

The stench from modern hog confinement sheds and waste ponds can often be smelled up to a mile away. Local citizens frequently complain of breathing difficulties, burning sensations in their noses and throats, nausea, vomiting, headaches, and sleeping problems.

“It makes you ill,” says Becky Bass, who lives a few hundred feet from a large hog farm near Wilson, North Carolina. Bass says she notices the smell "about 90 percent of the time.” Her husband, who works with hogs, “smells it and tastes it even hours after he’s been in the house.” Overpowered by the odor, her children are reluctant to play outside, and visitors sometimes hold their noses as they dash from their cars to the house.

A recent study at the Duke University School of Medicine confirmed the experiences of residents like Bass. Swine odors can have a serious psychological impact on surrounding residents, the study concluded, causing anger, irritability, loss of appetite — even breaking up friendships and marriages. The same conditions that jeopardize community health also imperil hog workers. Hog farming has always been a dirty and dangerous occupation, but the move indoors to large confinement operations has increased the risks. Hydrogen sulfide released from decomposing waste has killed hog workers, and accumulated methane has caused explosions.

“Fifty percent of all people working with hogs have one or more respiratory problems," says Dr. Kelley Donham, a professor of agricultural medicine at the University of Iowa. Donham reviewed studies involving more than 2,700 hog workers, and discovered that they commonly experience acute and chronic respiratory illnesses, including bronchitis and asthma-like debilitations. Although the long-term effects are still unknown, tests on stockmen show that permanent lung deterioration can occur within seven years.

The threat to community and worker health has angered many residents enough to band together to fight corporate hog farms. “It’s not fair to make another human smell feces and urine," says Don Webb, a former hog farmer who has organized hundreds of his neighbors near Stantonsburg, North Carolina. “To continue to put large conglomerate hog operations under people’s noses before the solution is found to the odor and water problem is wrong.” — M.L.K.

“I grew up in a community where every family had hogs,” he says. “The family farm is a way of life as well as a means of making a living. I don’t believe the wealth of this country should be concentrated in the hands of a few. I believe in a fair distribution of wealth, and I believe in family farms.”

Murphy’s Law

His employees compare him to H. Ross Perot. Political allies and adversaries see him as an effective power broker. Citizens who live near his operations say he’s ruining their lives.

Wendell Murphy pulled himself out of obscurity to develop a hog operation reputed to be the largest in the world. A slick businessman and a shrewd operator in the good ol’ boy network of North Carolina politics, Murphy has created an empire of more than 600 hog farms in the South and Midwest that rings up $200 million in sales each year.

Murphy is a small-town-boy-made-good. After earning a degree in agricultural education from North Carolina State University in 1960, he taught school before returning to his hometown of Rose Hill and opening a feed mill with his father in 1962.

Four years later the family started contracting with private hog farmers and selling the pigs to slaughter houses. Business boomed, and by 1986 Murphy had 95 contract growers and 23 company-owned operations raising around half a million hogs. Today Murphy Farms produces over a million animals each year.

In 1982, Murphy capitalized on his fame as a businessman to run for the North Carolina legislature. He served three terms in the state House and two in the state Senate, where he wields power on a variety of committees — including a seat as vice-chair of the Agriculture Committee.

"Murphy picks his fights — he’s a very good politician,” says Bill Holman, a lobbyist for the Sierra Club. "He doesn’t speak or throw his weight around unless he’s sure he’s going to win.”

As a legislator, Murphy has not been afraid to use his power to benefit his business. Over the years, he has introduced or supported a variety of legislation to aid large-scale farm operations like his:

Last year, Murphy sponsored an amendment to exempt feed lots for farm animals from tough state wastewater regulations, subjecting them only to less stringent federal rules. Though the House added penalties for illegal discharges to public waters, the amendment “certainly benefited Murphy Farms,” says Holman.

Murphy introduced a bill last year to make sure that counties could not apply their own zoning regulations to control the size of livestock operations. The measure passed. “Senator Murphy was promoting the hog industry," says Don Webb, a Wilson County resident who lives near Murphy operations.

Murphy has backed legislation to limit the liability of farmers from nuisance suits. The measure, explains Holman, would protect Murphy from being sued by citizens sickened by the stench of his hog operations.

Tags

David Cecelski

David Cecelski is a historian at the Southern Oral History Program, UNC-Chapel Hill. He is author of Along Freedom Road, which recently won a 1996 Outstanding Book Award from the Gustavis Myers Center for the Study of Human Rights in North America. (1996)

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)