“Because Someone Speaks Up”

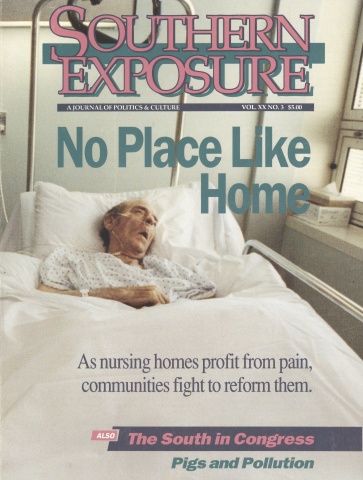

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

Fran Sutcliffe began the Nursing Home Hotline Patrol in Pinellas County, Florida in 1973, using a phone in her home as her base. Over the past two decades, she has earned a national reputation as an advocate of the rights of nursing home patients, and has been instrumental in passing laws to protect their rights on the state and federal levels. At the age of 80, Sutcliffe still receives and counsels 10 to 20 callers on the Hotline each day, and travels extensively to speak and lobby. Known as a no-nonsense person, she has little patience for bureaucratic delays. She relies on facts to get her points across and to push effectively for change. In March she was named to the board of directors of the National Citizens’ Coalition for Nursing Home Reform.

She spoke to Southern Exposure about the battle to improve the quality of life for nursing home patients, and the roots and impact of her activism.

When I was growing up, my mother was always involved in doing something for other people. I learned from her. Someone would call her up who needed help, and she was always taking care of them.

I was always a fighter. I worked for the United Nations Association when the United Nations was a dirty word. Eleanor Roosevelt was a dear friend of mine. I traveled to 30 states setting up chapters. When we were in Monroe, Louisiana, we held a group in the Methodist church, and they had a burning cross on the lawn the next morning. They used to throw bricks in the window when we spoke. I was with Adlai Stevenson when they attacked him.

People would say, “Why are you fooling with that?” My feeling was, people will only learn about the United Nations through controversy.

I got started in nursing home advocacy when I became responsible for a dear old lady who fell and broke her hip. Her name was Alice. She was an old family friend of my husband’s, in her 70s, and she lived alone. She went to the hospital, and the social workers called. “We’re sending Alice over to a nursing home,” they said.

This was in 1973, and I didn’t know a damn thing about nursing homes. I had never been in a nursing home. So I went and looked it over, and it looked like a pretty good thing. I said, “Fine, send her over.”

I went to see her every day, and I very quickly realized that I had to find out what was going on. It seemed like a good home, but I don’t take anything for granted. I began to look at laws to see what was right. That’s where I really got involved. If it wasn’t right, I spoke up.

People would see me at the home, and I guess they got to thinking that I knew something. A year later, I was appointed by the Florida governor to the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Council. There’s a statewide council and a local council in each district of Health and Rehabilitative Services (HRS). That was the beginning of the Florida ombudsman system.

We started from scratch, wrote the procedures for how to handle complaints, the forms, everything else. It was a long process. Now, everyone who checks into a nursing home must be given a brochure about the ombudsman system with a phone number to call if you have a problem.

I began the Nursing Home Hotline Patrol because the demand was there. I brought in a lady involved in the Quakers who was also very involved in nursing home care issues. We drove all over the county and visited every nursing home that summer.

A reporter from the St. Petersburg Times heard about us. She came over and said, “I want to do a story about this.” She wrote about us, and she gave us the name, Nursing Home Hotline Patrol. I had so many telephone calls after that. We offered a brochure that was mentioned in the article, and we got over 100 calls for it the first day.

We started Nursing Home Patrol meetings, once a month, then six times a year. We just put a notice in the paper and 40 to 50 people came. We taught federal laws and state laws, Medicaid and Medicare contracts, and insurance. After the patrol began, the hotline was automatic. We don’t have the patrols anymore, but the hotline is still going.

On the hotline, I get at least 10 calls every day, and it’s not uncommon for me to get 20 calls a day. Callers have very often gotten the runaround trying to do business with HRS, and they get a lot of wrong answers or no answers at all. Then my name comes up and someone says, “Call Fran, she knows the answer.” I do know the law.

Many of our calls are referred from hospital social workers or even HRS people. They’re asking about nursing homes, about where to go.

If I know a home is bad, I tell them, “Hell, I wouldn’t go there.” It’s my opinion. If they want to know why, I’ll tell them about the last inspection the home had. I know what the state inspectors are finding, and I’ll tell them about it.

I got a call from someone who wanted to put a relative into a home that’s considered one of the outstanding homes for Alzheimer’s patients. Well, the state report found 15 pages of deficiencies. I asked a nurse if things were really that way, and she said, “You’re exactly right.” People have called me and told me they’d never go there. It wasn’t a nice place.

The hotline covers Pinellas County, but I get calls from Philadelphia, Houston, people from all over the U.S. out-of-town homes, I have books here that give me ratings and some information about what kind of service they provide. I don’t recommend homes in other parts of the state like I do here, but I can give information and advice on things like Medicaid. Sometimes I can refer someone to the ombudsman office in a particular area. The other thing I tell people to do is to go to the library. In Florida, the state inspection reports are all there.

The last thing I tell these people is, “Let me know what happens to you. If you’re satisfied, if you have a problem, be sure to call me and let me know about it.”

I got a call from a lady I talked to seven years ago. She called me for advice about where to put her husband. “He was in a nursing home and it worked out fine,” she told me. “He’s gone now, and I’m going to move back home.” She just wanted to call and say thanks. It’s really rewarding to give people help.

What makes it possible for me to do this is that I absolutely never took any money from anybody. I refused grants. I pay my own way and say what I think and if they don’t like it, it doesn’t make any difference to me. Endless numbers of people are helped because someone speaks up.

Back in the ’70s, we had people in the Florida legislature who wrote excellent laws to protect residents’ rights. We don’t have them anymore. I expect that the next time the session rolls around, it’ll get worse. But back in the ’70s, the residents’ rights laws were very complete and very fine. When the feds wrote their laws in 1987, they followed them very closely.

During the administration of Governor Martinez, they refused to reappoint any of the experienced ombudsmen. We had excellent chapters that had done very good jobs. We lost a lot of good people, and it’s hard to rebuild that system. It’s hard to find dedicated people. There’s no pay and no glory in it.

In the last legislative session, Florida enacted new laws for something called adult congregate living facilities. The state has gone to the federal government for a waiver allowing them to use Medicaid funds for ACLFs. It’s part of a concept of “aging in place.” It may work, but I’m uneasy about it. We’re still writing the rules, and they’re fairly permissive. It sounds like it’s setting up mini nursing homes. That’s been my cry — the ACLFs won’t be subject to the regulations of a nursing home and could suffer from insufficient staffing.

To be in an ACLF, a resident cannot require 24-hour nursing care. That’s the primary consideration. So, in the case of an ACLF that offers several levels of care, who’s going to interpret how much care a resident needs? And who’s going to enforce it? It’s mostly been left up to the responsible party — the doctor and the family. After all, the administrator of the facility is making money, even if the person isn’t receiving the care they need.

We’ve always had the rule that anyone who requires seven days in bed has to leave the ACLF and go to a hospital or a nursing home. There’s been accommodations for certain conditions like a cold, and I never argued against that. But when state inspectors go in and cite the facility for having someone inappropriately placed, they have 30 days to have the person see a doctor.

I get a kick out of that. If people are inappropriately placed, they shouldn’t have to wait 30 days for a determination. Let’s stop kidding ourselves.

There are very few ACLFs where that really happens. Some are very well run. The irony is, the poorest ones are the ones with state patients, placed there by HRS. The poor ACLFs keep on going because of these state patients. It all goes back to the money.

The real problem in most nursing homes is that the staffing requirements are so minimal. The people in homes are a great deal sicker than they used to be because hospitals get rid of them quicker, and there just aren’t enough aides on staff at the homes to care for them.

We need better laws on staffing. I’ve gotten calls from aides who are upset because their supervisors wouldn’t let them finish work because they don’t want to pay overtime. They get discouraged and they quit and sign up with a home health care agency. Nursing homes say, “We can’t get good aides, good aides are hard to come by.” Don’t give me that crap. It’s the way they’re handled.

For the most part, aides do a good job. Florida has trained over 100,000 nursing home aides since we started training about five or six years ago. We started training here before it was required by the federal government, and we have good training schools here.

The training doesn’t do much good, though, when nursing homes get a tremendous amount of help from temporary employment agencies. Temporary aides come in for a little orientation, there’s your assignment, and that’s it. Nursing homes pay the agency no less than $12 an hour, and the help gets $5.

The problems on the federal level have to do with budget issues. Dan Quayle and his so-called committee on competition are the people who have hung up the regulations we’ve worked so hard on.

Nursing home owners in the American Health Care Association have been very successful in persuading the president to delay the approval of the rules for OBRA, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act passed in 1987. It was supposed to go into force on January 1,1992. Everyone agreed with these rules except for the American Health Care Association. They’ve waged one constant battle after another against reasonable rules that agree with the law. They claim it’s going to cost them more money. They say, “We can’t afford to do that.” That’s always their bitch.

The bottom line is money. They want to make more money than they already make. You have to understand: Everything today is run by big chains. We have 100 nursing homes in this area, and all but four are owned by chains. The chains tell the homes how much money they can spend, and that makes it pretty tough on the local administrators. There are very few companies that give them enough to do the job that needs to be done.

I feel sorry for some of these administrators. They really try very hard to run good homes, but they have so few funds to operate on.

The chains make a big difference in the operation. There’s no local control anymore. The regional director comes to town and walks into the administrator’s office on Monday morning and says, “How much money are you going to make me today?”

We have one chain here that’s always talking about their great units for Alzheimer’s patients. It’s “Alzheimer’s this and Alzheimer’s that.” When I see the big boys who run that chain at a conference, I say, “Hell, stop talking about Alzheimer’s and start putting enough money into the homes so the aides can do the job that needs to be done.”

But the federal government has sided with the chains. The Bush administration has been of the opinion that we need fewer rules, not more. It’s simply a way of accommodating the big boys, not only in nursing homes, but in every industry. Well, a new broom sweeps clean.

If you want to make them change, you have to hit them where it hurts — and the only thing they understand is money. The feds finally published the final rules for OBRA this week, and those rules provide for substantial federal fines. Right now, nursing homes that break the law just take a $ 1,000 fine and forget about it. The new law says they can be fined $10,000 a day for failure to meet regulations — and that begins to add up. I think that’s one way to get their attention. If we can get the states to enforce the new law, it will make a big difference.

Another thing that gets their attention is lawsuits. The nursing home owners in the Florida Health Care Association want to limit the rights of families and residents to sue for civil damages. But sometimes the threat of a lawsuit is the only thing that keeps a nursing home in line. It gets more problems solved than anything else.

Attorneys are very careful about taking on nursing home suits — it’s expensive, it’s time consuming, and they’re just not interested in getting that involved. But the nursing home owners are very paranoid about it. Well, if they were doing their jobs the way they were supposed to, there wouldn’t be any suits.

People always want to know what they can do. “I’m just one person with a problem,” they say. I tell people who are complaining, “Did you report this to the director of nursing, or to the administrator?” Very often, the problem is corrected right then. If it isn’t, I’ll call the home, and they’ll respond.

I often say to the administrator, “I know you want to run a good nursing home. You can’t run it if you don’t know what’s going on, and you can’t see everything all the time. I want to give you the opportunity to correct the problem before it goes further than me, and here it is.” Ninety-nine percent of the time they take care of the problem. If not, I get ahold of state inspectors and I tell them about the problem.

People have to be their own advocates. There’s no way this state can hire all the inspectors they would have to hire to correct all the problems. It has to come from concerned citizens.

When I speak to groups, particularly volunteers at nursing homes, they say, “I don’t have the authority to say that.” I say, “What do you mean? You’re a concerned citizen, and you’re calling attention to a problem they should be aware of. Nine times out of ten they’ll do something about it. They get away with things because no one says anything about it. Anybody can do it. I have a mouth, I can talk — that’s all it takes.”

I welcome controversy, I welcome questions. I don’t care what they are. I don’t have problems with administrators. They don’t love me, but they sure do respect me. That’s the way it is. I’m paying the bills, and that’s how I do it.

During my experience with Alice, it was so obvious to me that the families visiting patients were so hesitant to say anything. The residents were intimidated — and still are, to some extent. That’s why understanding residents’ rights and using them is so important.

We’ve had wonderful residents’ rights in Florida homes for years and got them on the federal level since 1987. But the rights only help if you demand them and use them.

For years, residents had to get up at 6 a.m. whether they liked it or not, and they went to bed at dark, and that was it. That doesn’t happen anymore. They get up when they want to get up and if they want something else to eat they can ask for it. They’re not as intimidated as they used to be, once they understand their rights. They need to know that they can still have an independent lifestyle if they want to. They can question things.

The problem is nobody wants to speak up. That’s really a terrible problem in this country. When anybody speaks up, they’re criticized and labeled as strange.

My advice to anyone who wants to make a difference — about nursing homes or anything else — is to learn the subject and speak up. If you don’t learn, you won’t have the confidence.

I never think about getting discouraged. When I started 20 years ago, nursing homes sure as hell weren’t as good as they are today. Now, for the first time, we have substantial residents’ rights in federal law. It’s going to be a long, hard fight to get the federal regulations rolling, to get them enforced. But it’s going to get better. I never give up.

I’m going to keep speaking up, and I’m going to keep working on the hotline. If you call and I’m not here, try again. I’m probably out in some nursing home raising hell.

Tags

Ellen Forman

Ellen Forman is a reporter with the Sun-Sentinel in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. (1992)