This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

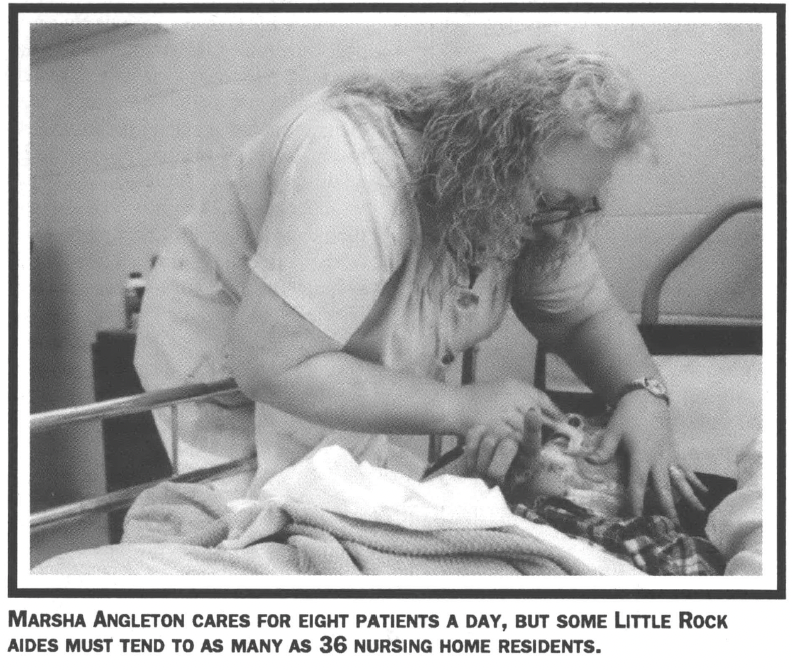

Little Rock, Ark. — Marsha Angleton likes talking with residents at Riley’s Oak Hill Manor, the upscale nursing home where she works as a nurse’s aide. Many of the patients are quite wealthy, she says, and have traveled to far-away places.

“One man had been to Africa,” she recalls. “He owned his own business, and I guess when you own your own business you can do whatever you want.”

Angleton, on the other hand, has rarely been outside of Arkansas, going only as far as Texas and Missouri next door. In fact, the annual fee residents pay to stay at Oak Hill Manor is about twice the $11,440 she makes each year, before taxes.

Yet Angleton shows little resentment about her station in life, even though it involves emptying urine bags and changing diapers. The only thing she regrets is not being able to become a beautician. Her father, who died when she was a teenager, farmed during the days and worked in a liquor store at nights to make ends meet. Marsha couldn’t afford beauty school when she graduated from high school in the rural town of Atkins, and she didn’t want to work at Burger King. That left nursing homes.

Angleton was 19 when she got her first job as a nurse’s aide at $2.60 an hour. After seven years at Oak Hill Manor, she earns $5.50.

Despite the low wages, Angleton considers herself one of the lucky ones. Unlike most of the 15,000 nursing home aides in Arkansas, she works at a well-staffed private clinic with fewer patients, safer working conditions, and slightly higher pay.

But like all aides, Angleton serves on the front lines of the nursing home industry each day. National studies show that aides provide 90 percent of the care offered in nursing homes. Almost all are women, struggling to raise families on their own. Most are black. And most receive little more than the minimum wage for performing dirty, back-breaking work.

Indeed, national surveys of occupational injuries show that nursing homes are among the most dangerous workplaces in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 15 percent of all nursing home workers experience injuries serious enough to be reported to the government — nearly twice the rate for private industry as a whole. What’s more, nearly half involve back injuries, among the most crippling and costly of injuries.

The low pay and dangerous conditions are driving many aides to look for other work. According to state officials, annual turnover at Arkansas nursing homes runs as high as 50 percent, and the national rate is close to 100 percent.

To get a glimpse into how hard an aide must struggle to do a good job, one need only spend a day at work with Marsha Angleton. Like other aides, she spends her days caring for the oldest and sickest members of the community — a tough and tiring job, even under the best conditions.

“Not every place to work is as good as this one,” Angleton acknowledges. “It all depends on if the nursing home owners care more about the patients than their pocketbooks.”

Nurse!

It is a few minutes before 7 a.m. when Angleton walks past the pine trees and landscaped yards dotted with crepe myrtle bushes that surround Riley’s Oak Hill Manor to begin her eight-hour shift. Unlike many nursing homes, Riley’s smells clean — the result, Angleton says, of good housekeeping. “Unlike some places, this place has enough good cleaning supplies and staff,” she says. “When you walk in the door, there’s no odor.”

Inside, the home has been recently remodeled. Yellow cinder-block walls have been painted mauve, with matching wallpaper and off-white baseboards. Some of the floors are carpeted, and tile floors carry a heavy, hospital shine. Wooden railings line the wide hallways.

Angleton clocks in and looks at her patient roster. The first duty of the day is to wake everybody up and get them ready for breakfast.

A few minutes after seven, the overhead lights come on in bootcamp style. Angleton and her co-workers begin opening doors and giving orders for the residents to wake up. The aides hardly sound like drill sergeants, however, calling their charges honey, darlin’ and baby. They ask residents how they are doing, eliciting responses from the grouchy to the incomprehensible.

Angleton changes diapers for some patients, helps others to the bathroom, and empties urine bags for those with catheters. A few residents can sit up by themselves or get into a chair for breakfast, but most need their beds raised to enable them to eat.

Getting so many people up and ready for breakfast can be the hardest time of the day, especially if there are not bed linens, diapers, or towels. Angleton says Riley’s tries to provide its aides with the supplies they need, though there never seem to be enough towels and washcloths.

Large carts full of food trays are rolled into the halls, the first of many vehicles that vie for space each day in the unregulated and never-ending hallway traffic at the home. Before the day is over, Angleton will walk miles — back and forth, up and down the halls — dodging laundry carts, 30-gallon diaper pails, mobile linen racks, and wheelchairs.

“Wake up Ellen, roll over, it’s time for breakfast,” Angleton says to one elderly woman as she carries in a tray of scrambled eggs and fruit juice.

“Hand me my teeth,” Ellen responds.

Once she finishes with Ellen, Angleton moves on to the next patient. “Be sure you tell Walter to eat,” another aide reminds her. Many residents at Oak Hill suffer from Alzheimer’s and Parkin son’s diseases, and their memories come and go.

“When it gets to when they don’t want to eat, you have to feed them,” Angleton explains. “Sometimes they get so confused, they don’t know to pick the spoon up. Their brain just doesn’t work.”

A little later, two patients get into a tug of war over a magazine. A woman in a wheelchair feebly kicks another woman before aides can get between them to break it up. A 93-year-old woman, also in a wheelchair, spends most of the day repeatedly asking for someone to come get her and take her home. She talks of visiting her sister on the second floor, although the building has only one floor. All her calls for attention begin with the cry, “Nurse, nurse!”

“Sometimes I pop off and say I’m going to change my name to Nurse,” Marsha admits privately in a rare moment of flippancy.

Abuse and Racism

Being flippant in front of residents is something Angleton knows not to do. Under strict federal and state regulations, even an off-handed comment can be considered verbal abuse — cause for firing. And once an aide is written up, the incident is recorded in a permanent record kept by the state Office of Long-Term Care. According to federal law, aides on the list can be barred from working anywhere in the industry for up to five years.

Nevertheless, verbal and physical abuse remains all too common. In a study conducted at Little Rock nursing homes last year by the University of Arkansas, more than 90 percent of the aides interviewed said they knew of residents being mistreated, abused, or neglected. In most cases, they said, an aide had yelled or spoken harshly to a resident.

Angleton gets angry when aides speak unkindly to residents. “My pet peeve is when a patient wants to go to the bathroom and someone will say, ‘Go in your diaper,’” she says.

The Little Rock study reported that abuse also takes the form of rough handling, which occurs frequently during bathing and dressing. Some aides said they knew of workers who hit and slapped patients, and in one case a female resident had been raped by a male aide.

Although aides have power over residents, die abuse can work both ways. “There is a lot of abuse inflicted on the aides by the patients,” says Shirley Gamble, director of the state Office of Long-Term Care. That abuse includes verbal, physical, and sexual. Some aides in the Little Rock study told of having their breasts grabbed by patients. In one instance, a male patient knocked a female aide to the ground several times. The aide finally hit him back — and was immediately fired. She was later rehired after the resident moved to a different facility.

Most of the aides interviewed for the Little Rock study also reported experiencing racism from patients and their families. Black aides reported being called nigger, coon, and jigs. “Who’s in charge of these niggers?” demanded a relative of one patient. “You can’t trust those blacks,” said another. Black aides also experience institutional discrimination. None of the nursing homes surveyed for the Little Rock study, for example, had any black registered nurses on staff.

At Oak Hill Manor where Angleton works, there is no indication of racial struggles between the aides themselves. White and black aides work side by side and often call on each other for help.

“We have to do a lot of teamwork,” explains Angleton. “If you don’t, you can’t function.”

Heavy Loads

As patient advocates have increased their scrutiny of the nursing home industry in recent years, lawmakers have developed new rules penalizing workers who provide substandard care. In 1987, Arkansas also enacted a law requiring nursing homes to employ only certified nurse’s aides who receive training. Later that year, federal lawmakers passed a similar regulation as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act to reform nursing homes.

But while such regulations are supposed to protect patients from mistreatment and poor care, they have failed to address the roots of the problem — the dangerous working conditions and heavy patient loads confronting most nursing home employees.

In Arkansas, most official complaints filed by aides involve understaffing. According to the Little Rock study, aides are sometimes responsible for as many as 36 residents on a shift—far more than one person can hope to care for in a day. The more patients they must attend to, say aides, the less attention they can give them.

Oak Hill Manor, where Marsha Angleton works, prides itself on having more aides on duty than the law requires. Angleton says she usually cares for no more than eight patients on a shift.

But even with fewer patients, the work takes its toll. The job of a nurse’s aide is physically demanding — lifting and turning patients, bathing them, making beds, pushing and pulling wheelchairs, helping patients walk and sit up. By 10:15 a.m. in her shift, Angleton is already showing signs of wear and tear. She sighs heavily, looking somewhat flushed from rushing around.

“I did hurt my back once and was out of work for a half a day,” Angleton says. Fortunately, she only pulled a muscle, and unlike some aides who wind up permanently disabled, she was able to keep her job.

Although it is the repetitive motions and heavy lifting that cause overexertion and injury, understaffing makes the situation worse. It is safer for aides to work in pairs when lifting patients, but the short age of aides on duty can make it hard to find a co-worker when you need one.

“When one worker is responsible for getting as many as 14 people up, washed, and ready for breakfast in as little as half an hour, finding and waiting for a co-worker to assist with a lift becomes problematic for both patients and workers,” reports a study by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the largest representative of health care workers in the nation.

“Taking longer with one patient means leaving others hungry,” the study continues. “It means having to skimp on care. The current levels of staffing simply do not allow workers to provide good care in a safe manner.”

Union leaders say Arkansas nursing homes are among the most dangerous in the nation, and they point to Beverly Enterprises, the largest chain in the business, as one of the chief culprits. “Beverly is the J.P. Stevens of the nursing home industry — the worst, slimiest company of the lot,” says Jamie Cohen, assistant director of health and safety for SEIU. “Health and safety is just not in their line item. They know that if they lose a worker, under the economy today, they can just Find another.” Beverly denies such charges.

To ease the burden of caring for so many patients at Oak Hill Manor, Angleton and other aides take turns feeding residents their lunches. During an average shift, aides receive two 10-minute breaks and a half-hour for lunch. Angleton spends her free time in the break room with a cigarette, a soft drink, and a bag of chips.

By noon, the aides have put bibs on their patients, and have begun cutting up their food and feeding them if necessary. Even the head nurse helps out. Marsha notices a woman who isn’t eating her lunch, a plate of chicken, rolls, peas and carrots, and fruit. She cuts up her meat for her.

“There you go,” Angleton says.

“No, you go ahead,” the woman replies.

After helping several other residents with lunch, Angleton takes a moment to visit a woman she knows who isn’t one of her patients for the day. The woman is eating in her room.

“You must have been busy,” the woman says when Angleton appears. “You haven’t been by to see me.”

Close Bonds

Such close bonds are common among nurse’s aides and their patients. Asked about the hardest part of her job, Angleton doesn’t mention the day-to-day stress, the fatigue, or her aching back. “It’s the dying,” she says.

“When someone dies, it’s a real hard experience. You’ve been with them day after day, and some of them can go down real fast. The patients become your family, and their families become your family. This place can really suck you in.”

Still, she says, getting to know the patients makes her job easier. “You have to learn when to tune them out and when not to,” she explains as she clips the nails of a patient. The woman has no family, and a local bank donates the money for her care. The aides at Oak Hill Manor have decorated her room with stuffed animals, posters, and coloring-book pictures of Disney characters. A game show blares on the TV screen.

“She’s a baby,” Angleton says. “There’s so many personalities in this place and you have to learn them real fast.”

Getting to know the families of patients also helps, says Angleton, especially when a new resident comes in. “The families are our bosses. You really have to feel the families out to find out what they want. When they first come in, it’s an adjustment. It’s the guilt, mostly. I try to tell them that I sympathize and try to do what they want right away, to build their trust.”

She helps another resident comb her hair and put on hand lotion. The resident is concerned she doesn’t have enough lotion, although two bottles sit beside her bed.

“You’re pretty as a picture,” the woman tells Marsha, who protests. “Well, you are.”

A Caring Family

After lunch, there is more diaper changing, part of the every-two-hour, diaper-changing routine required by law. Some residents go back to their rooms to rest. Others stay in the day rooms, strapped into wheelchairs, or propped up in lounge chairs. One woman wanders the hallway; another pulls herself along in her wheelchair talking to an invisible Grandpa.

By 1:25 p.m. Marsha begins filling out the day’s patient flow sheet. By law, she must note what she did for each patient that day — bed bath in the morning, blood pressure check in the afternoon, the number of bowel movements, and so on.

At 1:50 p.m. Marsha takes some final blood pressure tests. Ten minutes later it is time for bed check — taking residents to their rooms and changing diapers again.

Bed check takes nearly a whole hour. By 3 p.m. some patients head to the dining room to hear a guest singer. Marsha prepares to clock out.

The day has gone fairly smoothly. No one fell down, no one had a seizure or got too violent. The three-to-eleven shift arrives and Marsha meets her husband Gary outside to ride home to their trailer on a small plot of land just south of Little Rock. She tells Gary about her day, as she does every day after work. “If you can make it here,” she says, “you can make it anywhere.”

For relaxation, Angleton likes to go fishing with Gary and their eight-year-old daughter. Well, actually, she doesn’t fish, she admits. She likes to sit on the bank and read romance novels.

The women in Angleton’s family have a long history of caregiving. Her now-retired mother was a nurse, and always told Marsha she should also be a nurse. Even as a five-year-old, Marsha says she felt a sensitivity to the older people her mother cared for at nursing homes. It was her mother who was her teacher when she first began working as an aide. She taught Marsha how to walk a patient, how to change a bed. Angleton’s older sister is a psychiatric nurse, and her twin sister is also a nurse’s aide.

Yet her advice for others thinking of becoming an aide is: don’t. Go for the better pay, she says, unless you need to work as an aide first because you aren’t sure if you could handle being a full-fledged nurse. “I’d say go to school and become an LPN or RN.”

Coming from a nursing home aide as dedicated as Angleton, such advice speaks volumes. The job is simply too dangerous, too painful, and the pay is too low. If the nursing home industry is ever to improve the quality of care it offers, it will have to start by improving the jobs of women like Marsha Angleton. The more support nurse’s aides receive, the better care will be.

The aides, meanwhile, keep trying. “The pay is lousy, the work is hard, and there is little respect — but I try not to let that matter because I enjoy my residents and take good care of them,” one aide told University of Arkansas researchers. “I try not to gripe because one day I may be there — and I’m hoping I’ll get assigned to the good aide who cares.”

Tags

Anne Clancy

Anne Clancy is managing editor of Spectrum, a weekly news and arts alternative in Little Rock, Arkansas. (1992)