This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 2, "Money & Politics." Find more from that issue here.

Batesville, Miss. — Charles Nix is fighting an uphill battle. As executive director of the Panola County Chamber of Commerce, the 61-year-old former state senator presides over local efforts to develop a rural, working-class community where unemployment has hit 13 percent and federal support such as food stamps and social security accounts for one fourth of all income.

In the midst of such poverty, Nix says, one of the biggest impediments to prosperity is the lack of local control over credit. The six banks and one savings and loan in Panola have plenty of money to lend — $332 million in deposits as of June 1990. The problem is, those dollars are increasingly flowing out of the county. Two of three locally owned banks in Batesville have been taken over by an urban-based megabank, and one of two hometown S&Ls — Mississippi Savings Bank — went bankrupt and was closed by federal regulators.

Nix can remember when local financial institutions held almost every mortgage in the county. Today, few banks or thrifts in Panola make home loans. The biggest local source for housing credit is the former owner of Mississippi Savings Bank, who runs a mortgage brokerage out of his house. “More S&Ls and small banking concerns are being taken over by large banking concerns,” Nix laments. “Access to money at the local level is a thing of the past.”

Panola is not an isolated case. Across the South, hundreds of rural communities have been hard hit by the collapse of local savings and loans — and by government efforts to bail out the industry. In the rural South, the bailout is like global warming — most people know it’s happening, but they don’t understand how it affects them. Media coverage has focused primarily on the big Southern cities where the most dramatic failures took place.

To better understand how the largest financial calamity in history is affecting small towns and rural communities, the Southern Finance Project of the Institute for Southern Studies conducted a year-long study of the federal bailout. What areas in the rural South have been hardest hit? Who has bought thrifts that have failed? Have the S&L crisis and cleanup efforts made it harder to get home loans and credit for small businesses?

To answer those questions, the Finance Project tracked changes in financial institutions, branches, and deposits in 620 rural counties in 14 Southern states. The non-profit research organization also examined detailed information about 584 savings and loans that were sold or liquidated by federal regulators between August of 1989 and the end of 1991.

The findings are startling. Since 1989, the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) — the federal agency created to liquidate or sell hundreds of insolvent S&Ls and their assets — has handed over scores of small-town thrifts to big-city banks. The result has been a massive consolidation of financial resources and power with far reaching implications for communities throughout the South and the nation.

In just three years, the RTC has transferred more than a billion dollars in rural deposits to urban-based institutions, draining rural savings away from local needs like home loans and business credit. And in some areas, the agency’s sale of property held by failed S&Ls threatens to cut into local tax revenues that support essential county services.

“This just confirms what a lot of us in the rural South already suspected,” says Jim Hightower, former Texas Agriculture Commissioner and chair of the grassroots Financial Democracy Campaign. “The overall effect of the S&L bailout has been to shrink people’s control over their own money and to expand big bank control over everyone’s money.”

Plowed Under

The rural South was no stranger to financial calamity by the time hundreds of savings and loans started going bankrupt in the mid-1980s. Unlike many metropolitan areas in the region, most rural counties had not benefited much from the Southern economic boom of the previous three decades. As many major cities enjoyed an influx of jobs and money, the traditional mainstay of the rural economy — agriculture — had been declining steadily.

Between 1969 and 1989, farmers saw their share of regional income drop by half. Thousands of small and medium size farms disappeared, and many farmers sought second jobs to make ends meet. By 1989, farming accounted for more than one fourth of county income in only 25 of the 620 rural counties in the Finance Project survey.

Today the disparity between urban and rural areas is wider than ever. Almost a Fifth of rural Southerners live below the poverty level. Hundreds of counties lack doctors and adequate medical facilities. Population has declined in many counties, as younger people have migrated to urban areas in search of jobs. Federal assistance programs for farmers and women and children have been cut or eliminated, and county tax bases cannot keep up with local needs.

Half of the 620 counties surveyed rank among the poorest 20 percent of counties in the nation. In one fourth of the counties, the average resident earns less than $10,000 a year.

As rural communities suffered during the past decade, many of the local savings and loans that served them also faced hard times. For more than half a century, S&Ls had been quietly and conservatively financing homes across the country, paying small depositors three percent interest and lending the money to homeowners at six percent. It was a safe investment strategy, and it worked.

The trouble started in 1980, when Congress abolished ceilings on S&L interest rates that had been in place for decades. Thrifts were suddenly permitted to compete with unregulated money market funds, paying sky-high interest rates to attract “jumbo” deposits from wealthy depositors and Wall Street money brokers.

In the early 1980s, federal and state lawmakers went even further: They relaxed virtually every restriction on where S&Ls could invest their deposits. A new breed of go-go thrifts was born. Instead of investing money from small depositors back into local homes, high flyers like Centrust in Miami and FirstSouth of Arkansas solicited billions of dollars of deposits from Wall Street money brokers and plowed the money into office towers, strip shopping malls, junk bonds, and worthless land (see sidebar).

While thrift managers got fabulously wealthy from loan fees and salaries during the heady days of deregulation, the S&Ls they ran — and the federal insurance fund that backed them — went bankrupt. Two weeks after being sworn in as president in 1989, George Bush presented Congress with a plan for the largest and costliest bailout in U.S. history, a plan that even government officials say will cost taxpayers more than $500 billion. Eight months later, Congress passed the Bush plan and entrusted the cleanup to a new federal agency — the Resolution Trust Corporation.

Hometown Ruin

As the agency took control of property owned by failed thrifts, it quickly became the largest landowner in the world. By last December, the RTC had sold or liquidated 584 thrifts with a combined $212 billion in assets. Not since the emergency banking legislation of the New Deal has a government agency become so involved in the restructuring of the financial marketplace.

According to the study by the Southern Finance Project, the federal clean-up effort was centered in the South. A third of the assets involved in all RTC deals belonged to thrifts in just three Southern states — Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. Overall, 60 percent of all agency transactions between August 1989 and December 1991 involved Southern thrifts. By the end of January, 421 Southern-based thrifts had come under government control, and the RTC had inherited another 41 Southern institutions with $24 billion in deposits.

By far, the biggest thrift collapses in the region involved urban-based S&Ls that made risky investments in commercial office towers, hotels, townhouses, strip shopping malls, and undeveloped land in the suburbs. But dozens of small, locally owned banks and savings and loans that served rural communities also failed. And many rural branches were hurt by the wheeling and dealing of their urban cousins.

A close examination of government thrift deals in the rural South reveals widespread financial ruin: Rural Dollars. The RTC inherited big bucks from small-town deposits. Nearly half of all thrift deposits in the rural South — more than $5 billion — came under regulatory control between 1988 and 1991.

The hardest hit state was Texas, where more than 90 percent of rural thrift deposits came under regulatory control. In three other states — Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana — regulators took possession of more than 50 cents of every dollar deposited in rural thrifts.

But the damage was spread across the region. Regulators seized at least three fourths of thrift deposits in nearly 130 rural counties in the South. Communities where large thrifts had failed were particularly hard hit, especially in Texas, Arkansas, and Georgia.

Big Banks. Instead of giving communities control of their hometown thrifts that failed, government deals have concentrated rural deposits in a handful of large financial institutions.

In 16 early deals overseen by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, eight Texas buyers assembled extensive networks of rural branches containing $1.8 billion in deposits. Texas Trust Savings Bank of Llano acquired four thrifts with $494 million in rural deposits, and Sunbelt S&L of Irving picked up 12 thrifts with rural deposits of $363 million.

In the RTC deals, big banks were the big winners. Of the $2.1 billion in rural deposits distributed by the RTC, 74 percent were transferred to commercial banks.

More than half of every rural dollar went to large institutions — banks with assets of more than $1 billion, or S&Ls with more than $500 million. More than a third of the deposits went to just two commercial banks — Worthen Bank and Trust in Arkansas and NCNB in North Carolina. Other big winners included SouthTrust in Alabama, Citizens and Southern Bank in Georgia, Bank South and Trustmark National Bank in Mississippi, and First Gibraltar and Kilgore S&L in Texas.

Home Wreckers

During the mid-1980s, the savings and loan industry was at a crossroads. For half a century, thrifts had been dedicating most of their deposits to home mortgages, lending working families the money they needed to buy homes. But by 1986 a small, aggressive group of the largest thrifts had all but abandoned home lending. Instead, they were gambling with $44 billion in what was known as “hot money" — funds supplied by Wall Street money brokers.

Nowhere was the contrast between the old and new breed of S&L more pronounced than in the rural South. Fast-growing, urban-based mega-thrifts like First Savings in Arkansas, Unibank in Mississippi, and Sunbelt in Texas had expanded into small communities, competing directly with locally owned rural S&Ls.

The transformation was best exemplified by tiny Southern Building and Loan of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Like most thrifts in the region, Southern Building and Loan spent the 1970s quietly investing most of its deposits in fixed rate home mortgages to local homeowners. But all that changed in 1980. That was the year that Congress allowed S&Ls to offer higher rates to depositors — and the year that Howard Weichern took over as CEO of Southern.

With encouragement from federal bank regulators, Weichern adopted a fast-growth strategy for the $130- million thrift. His first move was to dramatically increase the interest paid on large deposits. Funds — from wealthy investors and Wall Street money brokerages — came pouring in.

The thrift, which changed its name to FirstSouth, invested most of its newfound money in loans for acquisition, development, and construction (ADC) of commercial property. Most of the ADC loans made by FirstSouth required no down payment by borrowers. Instead, the thrift loaned developers — frequently FirstSouth board members and shareholders — more money than they actually needed to develop properties into condominiums, shopping malls, or office towers. The borrowers then used some of the excess funds to “pay” FirstSouth lucrative loan origination fees. In effect, FirstSouth used this method to loan itself money.

Between 1980 and 1986, FirstSouth invested hundreds of millions of dollars in ADC loans, many of them secured by properties hundreds of miles away in Dallas or Palm Springs. With the blessing of federal regulators, Weichern purchased a dozen small, struggling thrifts and turned them into FirstSouth branches.

As FirstSouth abandoned home lending in favor of risky deals on resorts and condos, federal officials held Weichern up as a model of the new breed of thrift managers. Regulators never bothered to examine FirstSouth’s books between 1982 and 1985, even though the thrift’s assets more than doubled during that period.

By 1985, FirstSouth had 36 branches, five of them in rural Arkansas counties. But rural Arkansans were not the ones who benefited from this rapid growth. The average S&L in Arkansas devoted 37 percent of its assets to home loans; FirstSouth invested only eight percent. Instead, the thrift tunneled 46 percent of its $1.7 billion in assets into land grabs and commercial developments in faraway cities.

By the time regulators seized FirstSouth in December of 1986, they discovered that Weichern and his officers had hidden hundreds of bad loans from regulators and stockholders. What’s more, many loans that were not yet in default were unsecured. As many as two thirds of all FirstSouth loans were essentially worthless. The thrift appears to have been insolvent for years before regulators moved in, although Weichern continued to earn his $400,000 annual salary, report profits, and issue new stock. Federal regulators and stockholders sued Weichern alleging fraudulent practices, but the real culprit was federal policy that encouraged thrifts to wheel and deal. Former FirstSouth board member Gerry Powell told the Washington Post that the thrift carried out its disastrous fast-growth strategy “more or less as a directive from the chief of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board" in Dallas. Although taxpayers and shareholders were the big losers in the FirstSouth saga, they weren’t the only ones. By aggressively soliciting high-rate deposits, FirstSouth and its imitators throughout the South bid up the cost of funds for all savings institutions. The higher the cost of funds, the harder it became for S&Ls to afford fixed-rate mortgages. For small rural thrifts, the dramatic rise of megabanks and thrifts like FirstSouth meant a new era of cut-throat competition — an era that many did not survive.

Few of the new owners had ever operated in the rural counties where they acquired branches. In three fourths of the counties affected by RTC sales, rural deposits were transferred to institutions with no local track record.

Despite their lack of local experience, the big banks got a good deal. In addition to expanding their rural franchises, they bought rural deposits from the RTC at bargain-basement prices. In 14 Southern states, buyers paid approximately 1.6 cents for every dollar of deposits they obtained.

“Gold Bullion”

The numbers make clear that government deals helped transform the financial landscape of the rural South, fueling the trend toward financial consolidation. Between 1986 and 1990, the number of local S&Ls operating in rural counties declined from 107 to 63, while the number of commercial bank branches increased from 1,594 to 1,645.

As a result, large financial institutions significantly increased their share of rural deposits. In 1986, the largest banks and S&Ls held 15 percent of all rural deposits. Five years later, such institutions held 25 percent of all local money.

In fact, rural deposits in large institutions have soared by 96 percent since 1986, compared to an increase of only 19 percent for rural deposits overall. In five states — Georgia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and West Virginia — rural deposits in large institutions more than quadrupled in the past four years.

The RTC insists that the consolidation of money in big banks and thrifts won’t affect depositors and borrowers in small towns and rural communities.

“What’s the alternative?” says RTC spokesman Mark Burmeke. “If we can’t find a buyer, the institutions would just be closed down. How would rural communities benefit under that scenario?” But the numbers indicate that the trend toward bigger banks could make it harder for rural Southerners to borrow money for homes, farms, and businesses. According to the Southern Finance Project study, the bankers who acquired rural thrifts tend to be less interested in home lending than their predecessors were.

The eight institutions that acquired nearly all of the rural Texas deposits in 1988, for example, devoted between 4 percent and 20 percent of their total assets to home lending in 1990. The statewide average for Texas thrifts that year was 44 percent.

Similarly, most of the banks that acquired rural thrifts from the RTC devoted much smaller proportions of their total assets to home lending than did the thrifts they purchased. The two Arkansas thrifts acquired by Worthen Bank and Trust in the fall of 1990 each had devoted more than 25 percent of their total assets to family home loans. Worthen, on the other hand, invested less than 6 percent of its assets in family homes.

The result: Local borrowers are finding it harder to get a loan. “When Worthen took over, it was a loss of credit for the county,” says Charles Barnett, treasurer of Independence County, Arkansas. “They tend to invest our money in large chunks somewhere else rather than loan it out in the county.”

Many rural officials report that the new owners of their local S&Ls don’t seem interested in lending to local homeowners. After Magnolia Federal Bank bought First City Savings and Loan last July, “home buying just dropped off,” says Wilburn Bolen, a tax collector in Lucedale, Mississippi. “Some people have managed to get a loan from another bank or from a finance company that just opened an office here, but many put off buying a home because they can’t get credit.”

To make matters worse, local banks in rural counties where thrifts were sold or closed have not stepped up their home lending to make up for the loss of the failed S&Ls. Between 1988 and 1991, home loans by local banks declined or remained stagnant in eight of the 12 counties that lost a local thrift — including Marion in Alabama, Baxter and Poinsett in Arkansas, Habersham in Georgia, George in Mississippi, McIntosh in Oklahoma, and Karnes and Shelby in Texas. In the remaining four counties — Chatooga in Georgia, Red River in Louisiana, Panola in Mississippi, and Wayne in Tennessee — home loans by local banks increased, but only minimally.

The reluctance of local banks to increase their home lending suggests that residents in rural counties where the RTC sold or closed local S&Ls can expect to have a tough time getting credit. How tough? According to one county official in Texas who asked not to be identified, “You have to have gold bullion as collateral to get a home loan from the new S&L owners here.”

A Taxing Problem

Having a hard time getting a loan for a home or business may not be the only way rural residents are hurt by the collapse of the savings and loan industry. Rural officials and realtors also say the RTC is selling off the assets of failed thrifts at such rock-bottom prices that the deals may depress real estate prices and reduce property taxes that pay for essential county services. “The RTC recently sold four local properties for $40,000,” says Ricky Harris, a realtor in Chatooga County, Georgia. “Those properties had been appraised at $250,000.” Harris says he worries that the agency will sell the six or seven remaining properties it owns in the county for similarly low prices.

Harlen Barker, a county judge in San Saba, Texas, says that the RTC sold the office building of the failed Heart of Texas S&L — which cost $ 1.7 million to build — for $330,000. The lost money, he says, could have been used to help pay the cost of bailing out the bankrupt thrift. Instead, he says, “guess who picked up the tab?”

Such examples are not isolated incidents, if the RTC’s own real estate inventory is any indication. The average list price for rural residential properties in the inventory for July 1990 was $40,748. Fourteen months later, the average price had plunged to $25,817.

Some of the decline may have been caused by the sale of high-priced properties, which would lower the average price of remaining properties on the inventory. But figures show that the inventory is growing faster than the RTC can sell the properties, and the agency recently loosened its pricing guidelines — suggesting that the RTC has lowered prices on a significant portion of its rural inventory.

Many rural officials and residents also say that the RTC and its contractors are not marketing rural properties aggressively. A major problem, they say, is that the agency contracts with out-of-town realtors and asset managers to dispose of properties.

“The property I bought was under two or three different asset managers,” says Tom Martin, who spent nine months negotiating with the RTC over a modest, agency-owned home in Independence County, Arkansas. “It was transferred twice and I had to start the bidding process over each time.” According to Martin and others who have dealt with the RTC, agency contractors have little incentive to sell the properties in their charge. “Once the properties are gone, they can’t pull down any more fees,” Martin explains. “So they’re in no hurry to get rid of them.”

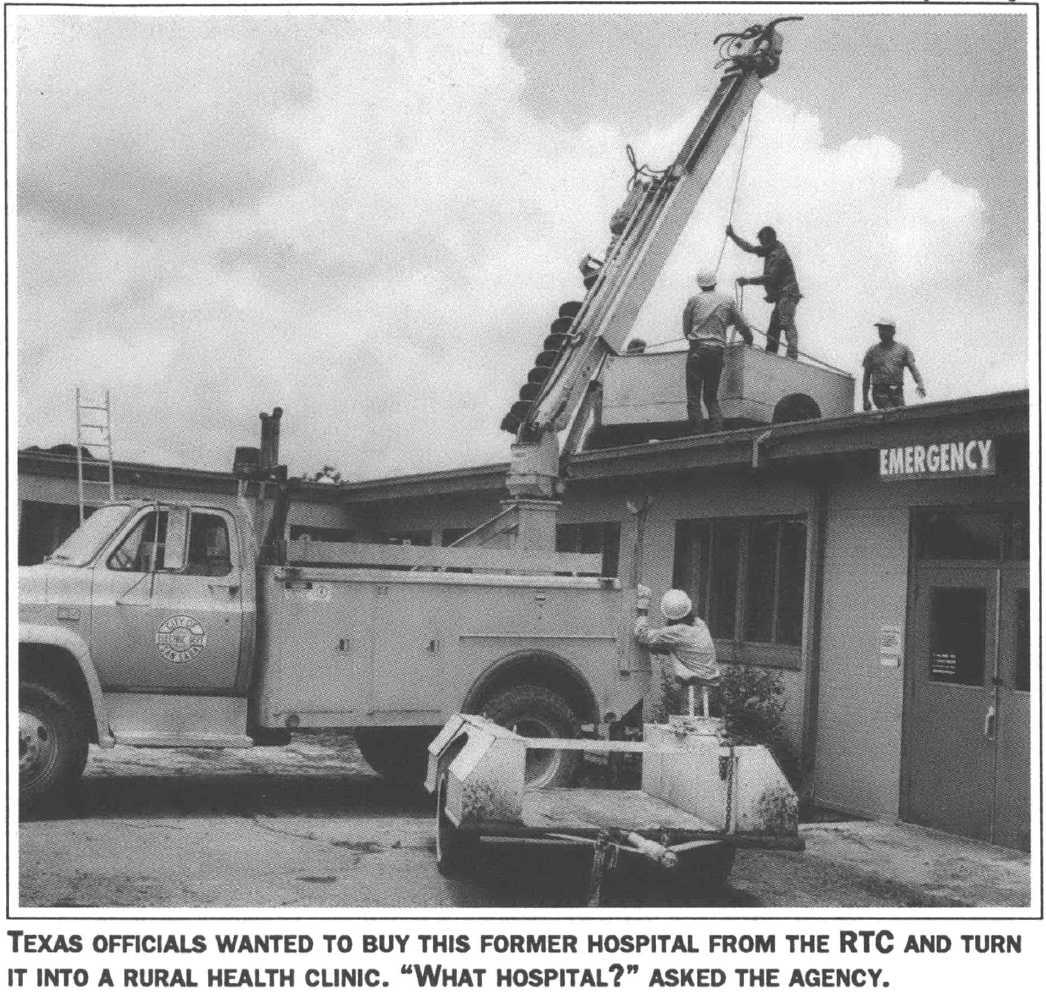

Harlen Barker, the county judge in Texas, recalls trying to obtain information from the RTC about a former county-run hospital on its inventory. The county wants to buy the building and turn it into a rural health center. “I called them up about it and they said ‘What hospital?”’ Barker says. “I really believe that if we called them up and said we found a million dollars that belonged to them, they couldn’t tell me where to send it or what to do with it.”

Indeed, the RTC has a poor record of keeping track of the properties it owns. The U.S. General Accounting Office has repeatedly ripped the agency for its shoddy recordkeeping. The first two editions of the RTC inventory, for example, listed more incorrect counties for Texas properties than correct ones. Rather than fixing the problem in subsequent editions, the RTC simply stopped listing counties altogether.

Similarly, the inventory omits or incorrectly reports vital information about property condition and appraisal value. When researchers with the Southern Finance Project examined the inventory, they noticed the address “625 Seagate Drive” listed for hundreds of properties in dozens of cities. It turned out the “address” is also a brand name for a common type of computer hard drive.

Mortgaging the Future

Some local officials report that residents in their counties had purchased properties at RTC auctions but could not obtain deeds and titles from the agency proving ownership. Ramage Appliance and Furniture Company of Mitchell County, Texas bought an RTC property last December and moved in before Christmas — only to receive an eviction notice from the RTC in early January.

County officials worry that underpriced and unsold property will diminish county tax collections. The danger is especially acute in Texas, where the end of the oil boom has driven down property values — and the taxes that county schools and other local services rely on. In rural Texas counties, a 10 percent decline in real estate values means a 10 percent decline in local school budgets.

Ray Mayo, a county judge in Mitchell County, Texas, says that poor handling of the RTC inventory has contributed to the decline in local property values. “Houses appraised at $ 100,000 are now selling for $20,000 or $30,000 — and tax appraisals have gone down to the purchase price.” Mayo estimates that as many as 30 homes in the county seat of Colorado City — a town of 5,000 — have been devalued.

In some cases, the RTC itself appears to have directly contributed to a drop in rural taxes. When Wilburn Bolen, the tax collector in Lucedale, Mississippi, sent the federal agency a tax bill for its properties in the county, RTC officials responded that government agencies are exempt from local taxation. And in Pecos County, Texas the RTC paid its local property taxes late — and then refused to pay the full amount of late penalties and interest due.

“It’s absolutely the biggest racket I’ve ever heard of, from the White House on down,” says Louise McCollum, a realtor in Chatooga County, Georgia. “The only ones benefiting are big banks that are not going to meet the needs of the community.”

According to many community leaders and activists, economic recovery in rural areas depends upon local control of lending. “If your hometown bank or S&L is bought by a big bank like NCNB, you’ve got to go to Dallas to get a loan,” says Jim Hightower, chair of the Financial Democracy Campaign. “The folks in Dallas have to ask the folks at corporate headquarters in Charlotte. And the folks in Charlotte aren’t very warm to the business possibilities in Liberty or New Deal or Ida Loo.” The answer, say Hightower and others, lies in stopping giveaways to big banks and creating financial alternatives that put money in local hands. “We need to decentralize banking and create a layer of community-based banks that support local needs,” Hightower says. “Federal policy should protect such community banks — not mortgage our economic future to big banks.”

Tags

Marty Leary

Marty Leary is research director of the Southern Finance Project, a non-profit organization sponsored by the Institute for Southern Studies. (1992)

Leticia Saucedo

Leticia Saucedo is former outreach coordinator with the Financial Democracy Campaign. (1992)