This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 2, "Money & Politics." Find more from that issue here.

To get him going, my sister and I would hum a union song that was popular among textile workers in those days. “Look for the union label....” The tune has a happy, light swing to it.

“All right, all right. Y’all go ahead,” he would say. “The union’s not paying your tuition.”

He knew we were only half serious, but he would often leave the room — his form of debate when the issue is close to the heart. Those issues are not many, but when you hit one his defense is silence. At the age of 14, I became an evangelist for atheism, and a couple of other isms that I knew would gall him, but he would never take me on. “You can make fun of me,” he once responded to my religious baiting, “but I would appreciate it if you would not make fun of my religion.” That single, knifing moment has haunted me ever since.

The union song, always a needle, became a broad sword one summer when, on break from college, I worked at the Angle Plant of the J.P. Stevens Company in Rocky Mount, Virginia. The Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union had targeted Stevens as its first major conquest in the textile industry, and a strong organizing push was on. Just whistling the union tune would send Dad running for the door.

My father’s education with unions began with his father. At a time when people lived in clapboard houses that the furniture company owned, in a section of town known as Needmore, my grandfather was a union man. He was never a union member, because at that time and in that place the union was only an idea some people had. Some people who weren’t very popular with the bosses.

When the paychecks came out in those days, a certain portion went right back to the company for rent. Another chunk went to pay off the A.O. Moran Store, which kept a tab. On some paydays, if the deductions were light, there would be tenderloin for supper. Needmore produced the men who are now the town’s civic and financial leaders. They are quick to tell you they “grew up on Needmore.” You grew up on, not in, Needmore, because the whole neighborhood was on a hill in back of one of the lumber yards. To the children of Needmore, it is just the name of a slight rise with several streets of houses. They say it the way people whose last names are Sawyer or Potter or Smith say their names. It is so intimate and often used it has lost any meaning it once had.

My grandfather’s work could not be questioned. My father’s house, and mine, now hold solid walnut furniture Granddaddy made, the kind of furniture you can’t even buy from furniture dealers these days. Some of the drawers, designed for holding items of precious clothing, have backs and sides and bottoms of cedar. From those drawers, you can put on a shirt or tie that is forty years old. Their smell is vivid as this morning.

My grandfather had no complete fingers on either hand. Some fingers were missing their tips, some were half gone, given to inattention on long afternoons in the furniture factories where he made his living. The furniture he made is worth thirty times today what it was then. Those solid pieces are still doing what they were made to do.

When Granddaddy had a heart attack and missed work for several months, he was “let go.” “He talked about the union too much,” my father says. Granddaddy was also only two years away from retirement. A man who is fired doesn’t receive retirement benefits.

This was a lesson my father cut into his memory. It was like holding my grandfather’s hand — you felt what wasn’t there more than what was.

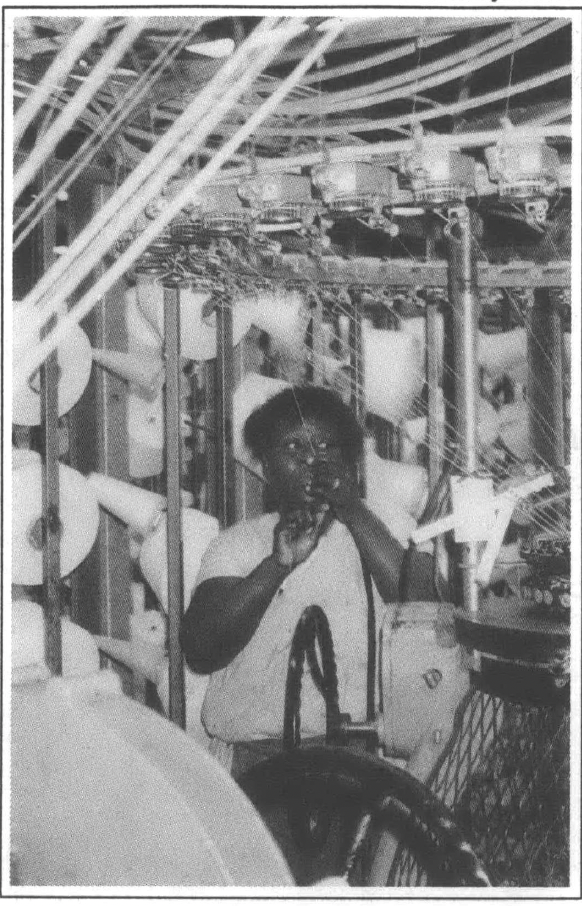

College boy, I learned how to change a light bulb, five hundred times. My job was to push a scaffolding over the rows of looms and change any of the fluorescent bulbs that were burned out. I had to take out all the bulbs and clean the tin shades with Fantastic.

I had the catbird seat on the whole weave room. I could see everyone — the cloth doffers, the weavers, the fixers, the smashers. It was a summer of conspiracies, and who was talking to whom was crucial. More crucial was who was not talking to whom when my father walked through the weave room.

“What do they want?” my father would say at the supper table. “They leave the furniture factories, even if they’ve been there several years, and make more money with our starting wages.”

That was true. Stevens was one of the highest-paying, if not the highest-paying, employers in the county. If you wanted better pay, you were looking at an hour drive, one way, to the DuPont plant in Martinsville.

I pushed my rickety tower toward September, watching the people between the rows of looms. To speak, they had to put mouth to ear as if whispering a secret. Actually, they were yelling, even in that pose, to be heard over the roar of the looms.

There was only one sound I heard that summer louder than the looms.

The idea of a union for this mill was redundant as far as I could tell. The employees here were bound by cords stronger than any union could make. I could look out over the weave room and see husband and wife, their children, brothers and sisters and cousins, half the congregation of the Methodist church, and most of the members of the Glade Hill rescue squad.

What could a union offer them? The issues I overheard from conversations outside the weave room were about things like a lunch room where you could eat in relative quiet and more vacation days. Of course, conversations tended to change whenever I came around. In a community that tight, it is no secret whose son you are.

It was the shank of the afternoon, the blank part when your blood is still humming from lunch and the drone of the day has lulled you. It is the time of day accidents tend to happen, the time when people have grown used to the flying, steel-tipped shuttle and the jumping harness, the time when they’ve forgotten how quickly a working loom can grab you.

That’s when the order came. My father walking quickly down the rows on one side of the weave room, the plant manager on the other, and almost in unison the looms shutting off.

Those days the plant was running at top capacity, three shifts working six days a week. The looms surged to life each Sunday at midnight and were not shut off until the following Saturday night. You could feel the vibration of their working in your shoes as you walked across the parking lot.

Only their sudden silence was louder than their roar.

It was a strike that would have delighted any military strategist. All the looms were shut down and everyone was gathered in the slasher area, which had been quickly cleared and filled with folding chairs. There was a lectern set up and Mr. Grey from the office in Greensboro was there. My father on his left.

Mr. Grey talked about the company’s desire to keep the union out, but it didn’t matter a great deal what he said. The silence in the two weave rooms made his point. This is what the plant would sound like if, for some reason, the company decided to shut the plant down. Afterwards some of the most ardent union people went up to my father and denied any union sympathies.

Before that summer was over, my father would have a handful of labor charges filed against him, and he would appear in court, proud of his stand for his company. The union continued to try to organize the plant, but the tide had turned. Around the house he wore the sweatshirt that was made available to all employees. It said, “Stand Up for Stevens.”

Despite a concentrated effort by ACTWU and dozens of workers, the union issue did not even come to a vote at the Angle Plant. When I went back to work at the plant the next summer, however, I found a new canteen with two microwaves, a refrigerator, a row of vending machines, and nice tables where you could have your lunch. On certain holidays, spreads that equaled what the Methodists and Baptists could turn out were offered in the canteen.

Given the history at Stevens, I was stunned to hear my father’s opinion not too long ago during a strike by coal miners in southwest Virginia.

“Well, maybe they need the union,” he said. “Sometimes the company has to be forced to do something.”

There was the waffling of the ‘maybe,’ and I knew he would probably recant later, which he did. I was still dumb-struck.

He was no longer a company man, for reasons beyond his control. J.P. Stevens, in a corporate takeover, had been swallowed by Westpoint Pepperill which, in turn, was eaten by a group of investors. Due to the lumbering debt incurred in the takeovers and new federal regulations that allow companies to provide lower benefits for salaried employees, the pension that my father will receive when he retires has been slashed in half. When he retires, he will have nearly four decades of service in the same building with many of the same people.

For all the years he worked for Stevens, he remained loyal. Then, in a couple months of frenzied buying and trading, his loyalty was mortgaged. He, like many other Americans, never left the company. The company left him.

Now, Japanese air jet looms are replacing the old Drapers in the weave rooms of the Angle Plant. Compared to the old looms, the air jets are like a whisper. In the weave rooms, it’s getting quieter and quieter.

Tags

Michael Chitwood

Michael Chitwood is editor of Hypotenuse, the magazine of the Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina. His book of poetry, Salt Works, will be published by Ohio Review Books in August. (1992)