This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 2, "Money & Politics." Find more from that issue here.

Whether putting through a fiberglass brontosaurus or banking off a troublesome windmill, few pursuits offer as silly a leisure experience as miniature golf. Forged by Southern fantasy in a mountaintop resort at Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, the tiny sport has achieved larger-than-life status as a genuine folk art—one that reflects the imagination and ingenuity of its regional roots.

The true origins of mini-golf remain shrouded in myth. Most reliable reports trace its birth to 1916, when James Barber built a course on the lawn of his private estate in Pinehurst, North Carolina. The diversion gained ground a few years later when a cotton baron named Thomas McCulloch Fairbaim discovered that compressed cottonseed hulls made an ideal putting surface. Fairbaim dyed and patented his discovery in 1925, creating the first artificial putting “green.”

The following year, Frieda Carter designed a miniature course to amuse guests at the Fairyland Inn resort run by her husband Garnet atop Lookout Mountain in Tennessee. Replete with elves and gnomes and hazards fashioned from hollowed out logs, the course rapidly became the main attraction at the Inn. Recognizing its commercial potential, the Carters patented the course in 1929 and named it Tom Thumb Golf.

Within a year, the amusing pastime had become a national craze; President Herbert Hoover even asked the Marines to build a course at his Maryland retreat for his son. Estimates put the number of courses at over 25,000 nationwide. Nearly 3,000 Tom Thumb courses earned the Carters over $1 million in royalties.

The small-golf mania began as a diversion for the wealthy, but the sport quickly attracted a wider following. Enterprising city kids created makeshift courses on corner lots with leftover construction materials. Women were thought to be particularly suited to play the game because of their “hereditary gift of wielding a broom day in and day out.” A few “coloreds only” courses were built—rigged, according to some observers, so the ball would not roll true.

For the first time, golf— or a miniaturized version of it— was accessible to Americans of all economic levels. On any given night, four million people could be found playing mini golf. The “Madness of 1930,” as it became known, provided not only a welcome diversion from the Great Depression, but also created thousands of jobs for cotton and lumber workers.

Despite the remarkable upswing in its popularity, miniature golf lacked follow through. By 1931, interest in mini-golf began to decline, and courses closed rapidly.

Once again, a Southern entrepreneur stepped up to save the game. One night in 1954, Don Clayton went golfing at a miniature course in his home town of Fayetteville, North Carolina. Clayton was recovering from a nervous breakdown brought on by overwork, and he decided to create his own no frills course.

“God just decided it was time for someone to do it and He said, ‘Don, you do it,’” Clayton recalls. The result was Putt-Putt Golf Courses, the most successful franchise in the industry. A fundamentalist at heart, Clayton disdained wacky obstacles and focused the game on the essentials of putting. “Hitting a ball into a kangaroo’s pouch is a game of luck, not skill,” he scoffs.

Putt-Putt is now a $100-million-a-year business with more than 300 courses in five countries. Half the courses are located in the South — in large part, Clayton admits, because “land is less expensive, laws are less stringent, and labor unions are less difficult to deal with.”

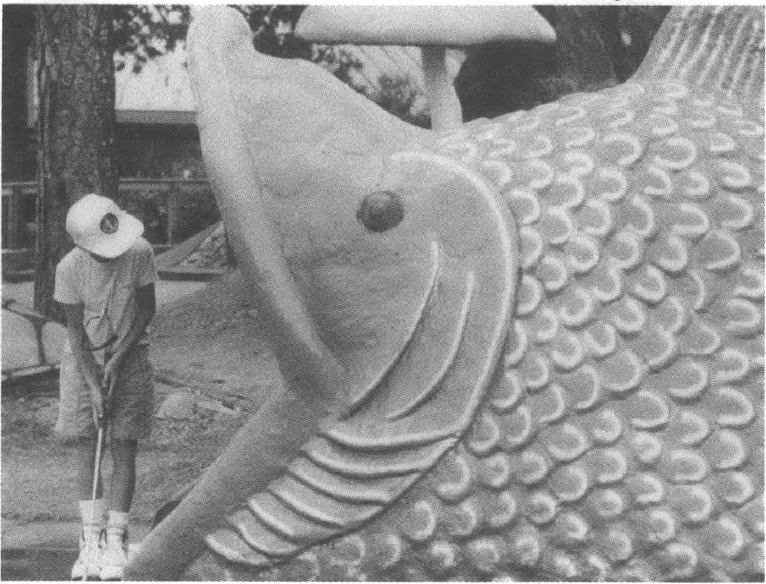

According to the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions, there are now 3,000 miniature golf courses nationwide—half built since 1980, and one third located in the South. The sport does a particularly brisk business at resorts like Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, recently crowned “Miniature Golf Capital of the World.” Nearly 50 courses compete to attract vacationers with flying saucers, fantasy animals, and gimmicks like the Hawaiian Rumble, a 40-foot “volcano” that erupts fire and steam every 20 minutes.

Although the Southern imagination has made mini-golf an integral part of popular culture, observers caution that its goofiness can be addictive. “It is easy to be pretty good,” says photographer John Margolies, who visited 150 courses for his book Miniature Golf. “But it is stupid to be very good.”

Tags

Harrell Chotas

Harrell Chotas is a research associate in the radiology department at Duke University Medical Center. His best score for 18 holes of Putt-Putt is 30 strokes. (1992)

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)