This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 2, "Money & Politics." Find more from that issue here.

Americus, GA. — Beckoning the goat into the barn, Bob Burns sings gently out the back door, “Wendy, shucka, shucka. Wendy, shucka, shucka.” The goat bounds into a wooden room that smells of straw and animals, and Burns milks her by hand. Normally a routine farm chore, the milking this day takes on the feel of history. It is part of a tour of the organic garden at Koinonia Partners, a Christian community in southwest Georgia that is celebrating its 50th anniversary on this sunny April afternoon.

Burns moved to Koinonia four years ago to practice organic, self-sustaining gardening. During the tour, he shows visitors how residents use discarded cardboard and peanut shells to mulch the tomato patch. He points out the fence they erected around the orchard to allow chickens to eat insects in fruit that falls to the ground. The chickens eliminate the need for pesticides, he explains, and their manure fertilizes the soil, continuing the cycle.

To Burns, the community garden symbolizes the importance of Koinonia. Like hundreds of others who have joined the religious community since its founding in 1942, Bums says he came here to live out a vision of a new society, an alternative way of life.

“The problems of the whole world are encapsulated in small communities and we have to deal with them healingly,” Burns says. “I don’t want to make grand changes. I want to take care of my little patch of ground and a few interpersonal relationships.”

Yet over the past 50 years, the seeds of change sown on this little patch of ground have spread across the world. Founded as a modest experiment in communal living and racial harmony, Koinonia helped spark the Southern civil rights movement, gave rise to the international organization Habitat for Humanity, and forged bonds between whites and local black residents that forever broke the grip of racism and violence in Sumter County.

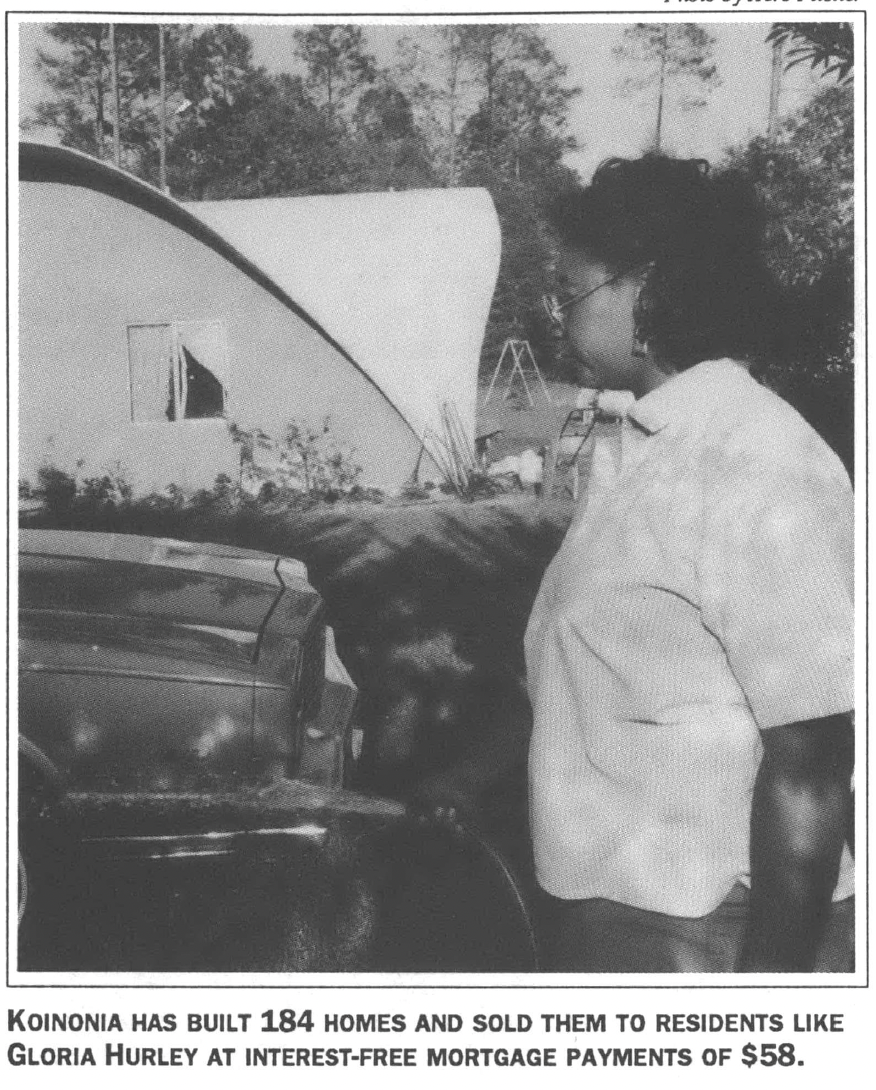

The continuing legacy of Koinonia is evident throughout the anniversary tour. Nearly 400 former residents and volunteers have returned to the community to celebrate their history today. They visit the 500-acre farm, the bakery, the mail order business, and the Child Development Center. They gather under a large canvas tent to rejoice with 15 Sumter County families who have paid off interest-free mortgages on homes they purchased from Koinonia.

Such programs were at the heart of the community’s original vision: to help local black sharecroppers and tenant farmers overcome poverty. For black residents of Sumter County, Koinonia provides jobs, a pre-school learning center, summer youth activities, low-cost homes, and home repair services.

But today, half a century after Koinonia began its historic struggle to promote racial harmony, the mostly white community finds itself challenged to adapt to the changing dynamics of race relations. Weary of “white heroes,” many black neighbors and employees have begun to question the “integrated” institutions created by Koinonia. They are setting their own terms for racial and economic justice — and prompting many white Koinonians to examine whether their vision of Christian love and compassion contains the very attitudes of paternalism they seek to overcome. “We learned in a workshop with our employees a few years ago that the very people we’re trying to be in partnership with are afraid of us,” says Koinonia coordinator Gail Steiner. “Many residents were not willing to recognize that racism is built into the system.”

Bullets and Pecans

Koinonia was founded by the Reverend Clarence Jordan, a radical preacher, theologian, farmer, and storyteller from Talbotton, Georgia. Clarence — everybody called him Clarence — was disgusted by a white Baptist church that worshiped lofty steeples while crushing poor Southern blacks with segregation.

“Jesus probably never suspected his gospel would dead-end at a massive ecclesiastical structure,” Clarence declared. “We have been trying to eliminate Jesus by worshiping him.”

Along with his wife Florence and another couple, Clarence founded Koinonia Farm to serve as a dissenting witness amid the complacent Southern Christianity and white privilege of Sumter County. The founders rejuvenated 440 acres of eroded land and taught farming methods to their black neighbors. They shared their possessions and income, replacing competition with cooperation. They ate lunch with their black hired hands and drove black children to school. They paid good wages when most Southern black farmers were exploited by sharecroppers. They preached pacifism during the Korean War, and they opened their farm to civil rights workers. Word got around.

Then one morning in 1956, white residents in Sumter County awoke to read in the local newspaper that Clarence had helped two black students integrate an Atlanta college. Koinonia became a target of bullets, vandalism, bombs, judicial persecution, and a countywide boycott of their produce. To survive, residents of the farm used their newsletter mailing list to start a mail-order business selling shelled pecan products.

“When we stayed and didn’t run, I think it did change the lives of people here,” says Margaret Wittkamper, who has lived at Koinonia longer than any other resident. “It gave them something to think about. I think Sumter County was greatly influenced by the presence of Koinonia.”

The mail-order business helped sustain the community during the decade-long boycott, but the violence and economic pressure took its toll. By the mid-1960s, the population of the farm had dwindled from 60 people to only two families. Clarence felt that Koinonia was too isolated. Basic social conditions, he concluded, could not be changed by mere kindness.

Then Clarence met Millard Fuller. A millionaire by the time he was 28, Fuller was dissatisfied with his life. He went to visit a friend at Koinonia for two hours in 1965 — and stayed for a month to talk with Clarence. Three years later, Fuller sold off his estate and came to Koinonia Farm with his wife Linda to help rebuild the community.

The result was Koinonia Partners, a non-profit business and ministry designed to empower the poor by transforming the economic structures that hold them in poverty. Under Fuller’s leadership, the mail-order business dramatically increased its sales, and the rejuvenated farm showed a profit. Surplus income and donations went into a “Fund for Humanity” to provide capital to help displaced black farmers start their own businesses.

Hundreds of white people streamed to Koinonia to help the poor and experience Christian community. They created a housing program to build homes and sell them cheaply to black residents living in dilapidated shacks. They opened a preschool for black children, supported the integration of public schools, and registered black voters. They started a sewing industry, a pottery industry, a pig farm, a worm farm. They helped local residents become independent contractors and pulpwood truckers.

“It seemed a new industry was launched every week,” recalls Don Mosley, who lived at Koinonia for eight years during the 1970s and now serves on the board of directors.

“We were forcefully putting our faith to the test by pushing to the very limit of our resources,” recalls resident Bill Londeree. “We believed that our cause was just, that if we did all we could toward that just cause, some good would come of it.”

Boom and Bust

During the 1970s, the Koinonia mailing list grew to 30,000. Partnership newsletters in those days were filled with words like expansion, growth, progress, and industry.

But the rapid business development soon overwhelmed the community, and the stream of newcomers ebbed. Millard Fuller left to begin the housing organization Habitat for Humanity, which expanded the Koinonia model to 820 cities in 34 countries. Three other families left to establish Jubilee Partners, a sanctuary for Central American refugees in Comer, Georgia. Before long, the optimistic words in the newsletter had disappeared.

“Out of maybe a dozen new industries started in 1970, only two existed in 1975,” says Don Mosley. “Reality set in. We found it was a lot more difficult than we thought.”

According to a 1979 newsletter, most of the industries had experienced “a long series of slowly evolving changes” that were straining community finances. Most were subsidized by Koinonia funds and volunteer labor. Those that were turned over to local residents always seemed to fail.

The longest-running venture — a grocery co-op — seemed an ideal partnership with local residents. Its bi-racial board operated independently of Koinonia, selling food at wholesale prices to all-white Koinonia and its black neighbors. It also served as a popular and diverse meeting place.

But co-op sales began to drop, and many members stopped paying their dues and contributing time to operate the store. After tense and painful discussions, Koinonia decided to close the store — ending the era of “partnership industries.”

“Those businesses weren’t begun or ended lightly,” says Mosley. “We worked hard to keep them and agonized over cutting them back.”

Today, 42 people live at Koinonia. The nationwide mail-order business begun during the local boycott continues to prosper, grossing $600,000 in fruitcake, nuts, and candy last year. The housing program has built a total of 182 new homes for local residents. But most of the industries Koinonia developed in partnership with local residents are gone.

Why did this frantic, often frustrating economic experiment finally wind down? Some say the industries expanded too quickly. Others blame the lack of market research. But these days, many Koinonians are doing some soul searching. They are looking within themselves for the answers — and they don’t like everything they have found.

Poverty and Power

When Koinonia first began building houses for local residents next to the farm, they sent crews to clean up the property and remove junked cars. They made emergency loans to residents, many of which they forgave. They formed maintenance crews to repair homes cheaply.

“They really helped the poor people,” says Mamie Lee Bateman, who has been paying an interest-free mortgage of $58 for 16 years to buy a home from Koinonia. “Before I got this house I lived in a place where I had to put a tub under one side to catch the water when it rained, and I still had to pay $25 a month.”

Most white Koinonians thought of their housing program and local industries as acts of Christian kindness and compassion that created security and independence for their black neighbors. To their surprise, however, they discovered that many black residents also felt powerless and angry.

Three years ago, white residents received a letter written by their two dozen full-time employees — all but one of whom was black. The workers stated that all was not well. They wanted to talk, so Koinonia hired a consultant to facilitate a workshop.

“It’s like marriage,” says coordinator Gail Steiner. “You fall in love and everything looks great. Suddenly you have to share the same bathroom and things don’t look so great.”

Employees said they had not spoken up before because they were afraid they would be fired. White residents were shocked. They were aware of the cultural differences between themselves and their neighbors, but they had grown accustomed to the comforting rhetoric of “partnership.” Only when black employees felt free to speak honestly did their white employers begin to see the dynamics of racial and economic power inherent in their relationship.

One employee said that white Koinonians do not understand the vulnerability of local workers. “If things don’t work out, they can move back into society and pick up where they left off,” the employee said. “Well, the neighbors don’t have that feeling.”

Employees who worked at Koinonia for years found themselves repeatedly training their own supervisors, as white residents switched jobs or left the community. According to one employee, the implicit message was, “Because we’re black, you don’t trust us. We were saying, ‘You’re the corporation, but we’re the consistent part of this operation.’”

Koinonia, like many mainstream businesses, discovered it has a “glass ceiling.” White supervisors came and went, while blacks were shut out of positions of authority. Without thinking a single racist thought, Koinonia had perpetuated some of the very aspects of economic paternalism that Clarence Jordan had imagined the community subverting. “Business priorities” at Koinonia were set by a white agenda, and “local needs” were interpreted by a white institution.

“They had a tendency to set up things in their interest, and not necessarily in the interest of the community,” observes B.J. Jones, an employee who is purchasing a home from Koinonia.

The cooperative store, despite its bi-racial board, “was always perceived as the company store,” says one neighbor. “It’s a pretty classic example of the company directing the conversation and flow of traffic.”

“For many blacks, it was ‘Koinonia’s store,” agrees Mildred Burton, a long-time Koinonia employee and homeowner who helped run the coop. “It was hard to get the message over that it’s not Koinonia’s store, it’s our store.”

Culture and Lore

The discussions about racism and paternalism have been hard for many residents at Koinonia to accept. “There have been people here who haven’t been willing to admit the power that we as white partners have,” says Steiner, the community coordinator.

The community has bravely supported racial justice, but it has rarely been integrated. Koinonia attracts white Christians who, as an act of conscience and solidarity, take a vow to give up their possessions and live simply. Many black residents in Sumter County, on the other hand, have no such desire to shun material possessions.

“Many people in the county have sharecropping memories, and they’re not about to go back to that,” says resident Bob Burns. “We have no right to ask them to relinquish what they have.”

When white residents at Koinonia try to make sense of the race relations with their black neighbors, they sometimes sound like a parent discussing how to let a child grow up. Some say they regret that they have not “taught their values” to their neighbors. Others say that partnership industries failed because local residents “did not understand” the concept of cooperative ownership or simply “preferred to be employees.” Even when speaking of ending paternalism, the tone remains.

Both blacks and whites acknowledge that it is difficult to transfer entrepreneurial energy to people who have little history of ownership, and that Koinonia’s efforts at partnership have not always been reciprocated. “They’ve been exploited by some people they helped,” says Eugene Cooper, who works as a liaison between Koinonia and homeowners.

Blacks and whites also acknowledge the meaningful personal relationships that have developed between white Koinonians and their black neighbors and employees. At a local crafts group that meets each Tuesday, for example, whites and blacks sit side by side recaning old chairs or making lap quilts for a nursing home. “That’s one of the most integrated activities we have,” says one Koinonia resident.

But by listening to their workers and neighbors, Koinonians are learning the limits of a white institution. Koinonia cannot be a good neighbor, it appears, without serious reflection on the structural relationship overlaying the personal relationships.

Koinonia is supported by its mail order business and its row crops of com, soybean, grapes, and peanuts. But it is no longer the self-sufficient farm that Clarence Jordan envisioned. Today the community also lives off donations, loans, and money from the house payments made by local residents. And that, some residents now say, raises the question: Who is dependent upon whom? Indeed, Koinonia depends on its neighbors for much more than labor and mortgage payments. As white residents come and go, it is the people of Sumter County — those who have lived on the land for generations — who provide the farm with its communal memory, its local culture and lore.

“It’s really our employees and neighbors who are committed here,” acknowledges coordinator Gail Steiner. “That’s been a big fault of ours: to have not been more respectful of the longevity and rootedness of the people here. Let’s face it. We’re the ones out of our culture.”

Most of the current residents have been at Koinonia for less than five years. Most are not from the South, and they know little of the racial traditions embedded in Southern culture that they are trying to change. “Southern people, once committed to racial justice, do better than others because they have usually lived with blacks,” says Eugene Cooper, the community liaison.

Koinonia has people of vision and generosity, but they lack familiarity with their own countryside. Many local residents, by contrast, have roots that stretch back well before the Civil War. Carranza Morgan, a local black farmer who serves on the board of Koinonia, owns and tills the same land as his grandfather. “This is the only place I know,” he says.

Listen and Learn

As Koinonia turns 50, its ear continues to strain in many directions: toward God, its neighbors, its supporters, and even toward its visitors and volunteers. “This is a second guesser’s paradise,” says Rock Francia, an employee who manages the farm business. “Everybody comes, whether have

for two days or two months, and says, ‘Why doesn’t Koinonia do this, or why don’t they do it this way?”’

Some wish the community would focus more on peace and justice work; others urge a greater emphasis on community life. Koinonia is, in a sense, a victim of its own success. Because the community is so dynamic — “more stimulating than the average gettin’ dirty farm job,” as Rock Francia says — it attracts people seeking an experience, a place to serve or experiment. Many stay for only a short while before moving on, creating a transient culture profoundly different from the enduring culture of Sumter County.

Many of the most difficult questions these days center on the housing program, Koinonia’s only long-term “partnership” with local residents. Community members are struggling to determine their relationship with people who own their own homes but still live in poverty.

Some have suggested ending the program of providing home maintenance, arguing that it fosters dependency among local residents. Tim Lee, a five-year Koinonia resident, says the community may start a homeowner association to encourage the local neighborhood “to take more responsibility for itself.” He says that residents of Koinonia would like simply “to be good neighbors” instead of adopting the paternal attitude of the past. “You’re not always watching a neighbor and as soon as you spot their needs run over and meet it for them,” he says.

But Koinonia employee B.J. Jones, who also serves on the board of directors, argues against the suggestion that ending the home-maintenance program will undo paternalism. “I understand what they’re saying, but there is a better way of nurturing the homeowners towards independence,” she insists.

According to coordinator Gail Steiner, however, the future of the home-maintenance program may be a moot point. “The skills are there, but the interest is not,” she says. “The people who have been doing it are burned out on it.”

Some black employees are worried that more structural change is needed to foster the positive atmosphere created by the workshop three years ago. “There’s a tendency to return to old routines,” says Eugene Cooper. “Some problems get pushed to the back burner.”

B.J. Jones agrees. “It’s something we’ve let slide a little bit,” she says.

Still, there is an air of expectancy and excitement at Koinonia as residents struggle to redefine their place in the story of Sumter County. Koinonia may pioneer a new form of racial partnership. There are a small but growing number of black-owned businesses in the county, and Koinonia employee Mildred Burton says she intends to open her own crafts store. If she does, Koinonia could be the spark for a locally owned crafts industry — a slow process, residents admit, but a highly satisfying one.

Although many white authors have written about Koinonia, some say the complete story will be known only if there is a “people’s history of Sumter County,” written by a black person about that black community, beginning at least 250 years ago. It will be a long and fascinating story — and Koinonia will emerge, eventually, here and there in the narrative.

Such a perspective — one that places the local black culture in the foreground, and treats Koinonia as a relative newcomer — could be seen at a recent meeting of the Sumter County NAACP in a local black church. George Theuer, a white resident who was leaving Koinonia after 17 years, was invited to the meeting and was thanked for his involvement and commitment.

Local residents then launched into the kind of discussion that could never happen at Koinonia. The topics were the same — racism in public schools, the need for voter registration — but black residents brought to the talk a depth of emotion beyond the experience of Koinonia, the strain of a shared struggle for respect and justice.

One man called himself and others at the meeting to task for being comfortable amid great need. A woman fretted that children are not being taught family values. Many spoke of frustration at their years of prolonged poverty.

A teenager rose and said the group should plan a march to make a statement to Sumter County, to demand racial and economic justice. “Our generation is not as tolerant as yours,” he said. Older members, speaking from their experience and wisdom, advised against the march, but they were moved by the young man’s anger and zeal. As the evening wore on, the two generations met and talked. Years of local history and culture wove through the discussion. And through it all, George Theuer sat. And listened.

Tags

Jerry Gentry

Jerry Gentry is a freelance writer in Decatur, Georgia. (1992)