This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 2, "Money & Politics." Find more from that issue here.

Charleston, W.Va. — It’s six o’clock in the evening a week before the May primary, and the campaign headquarters of David Grubb buzzes with activity. Grubb, a 41-year-old member of the House of Delegates who is vying for a seat in the state Senate, hunches over a pencil-marked mailing list. Across the table from the candidate, volunteers stuff and stamp envelopes. The phone rings incessantly, and Grubb mutters to no one in particular about a recent newspaper poll.

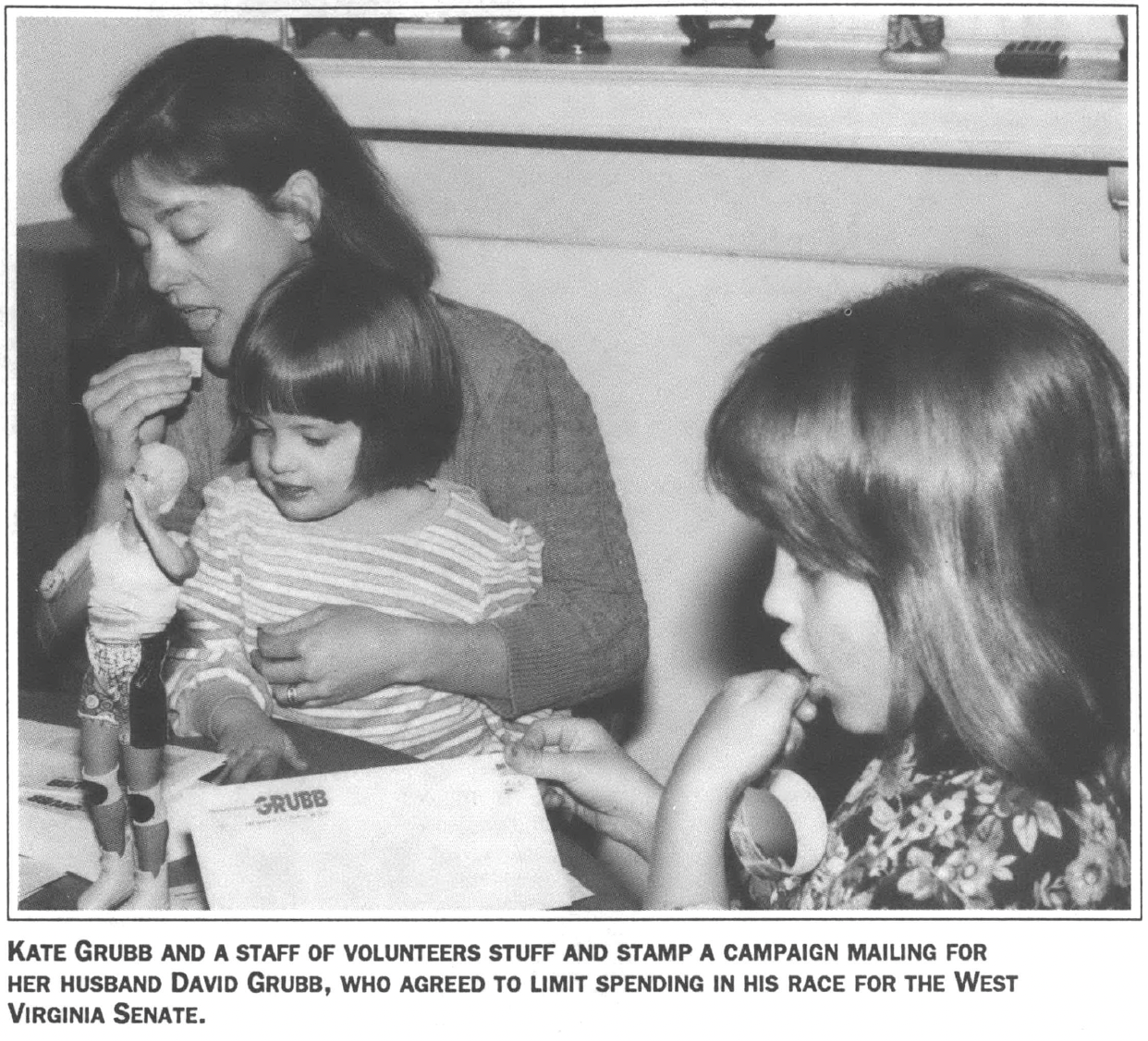

“Emma, don’t even think about throwing that ravioli at your father.” Grubb’s wife Kate shoots a warning glance at their three-year-old daughter, who is leaning out of her highchair. “Katherine, get those stamps out of your mouth and take Barbie and Ken off the table and clear a space so we can eat,” she adds.

The volunteers — eight-year-old Katherine Grubb, seven-year-old Jessica, and their neighbor Faith Davis, who is six —jump up and start shoving what’s left of the campaign mailing to one end of the dining room table. Grubb for Senate can wait.

Kate estimates that she and the girls have stuffed and stamped about 5,000 pieces of campaign mail. As the de facto campaign manager, she often balances Emma on one hip while she fields calls from reporters, talks strategy with volunteers, or sets up speaking engagements for her husband.

“It’s been like this all spring,” she sighs. “It will be wonderful to settle back into a routine lifestyle. I really look forward to that.”

Grubb decided to campaign with low-cost mailings from his family’s toys strewn duplex because he did something rare for a politician: He signed a pledge agreeing to limit his campaign spending and run an honest race. Known as the Code of Fair Campaign Practices, the pledge puts a $25,000 ceiling on state Senate races — nearly half what the average candidate spent to win a seat six years ago.

Created in 1988 by Secretary of State Ken Hechler and a coalition of reform activists, the Code is at the heart of an effort to get a grip on the undue influence of private money in West Virginia politics. By pressuring candidates to limit spending, Hechler and others hope to curb the skyrocketing cost of running for public office and reduce the need for candidates to go to wealthy contributors to finance their campaigns.

“The wellspring of democracy was being polluted by huge campaign spending,” says Hechler, who served in Congress for 18 years. “It was absolutely necessary to cap spending to allow young people and those who couldn’t afford the current trend to participate in the democratic process.”

Family Fortunes

Nowhere is the need to control campaign spending more apparent than in West Virginia. Although poor and small — the state ranks 49th in per-capita income and 41st in land size — it is fourth in the nation for spending on gubernatorial campaigns. Candidates for governor in 1988 spent a combined total of $9 million — $13.12 for each vote cast.

The two most expensive campaigns in state history were both waged and won by former governor John D. Rockefeller IV. When the Democratic incumbent drew on his family fortune and devoted $11.7 million to win re-election in 1980, supporters of Republican opponent Arch Moore put out bumper stickers that read, “Make Him Spend It All, Arch.” Rockefeller partisans responded with the slogan, “At Least It’s Jay’s Money,” a thinly veiled reference to charges that Moore had accepted illegal campaign contributions.

Rockefeller went on to spend $12.1 million on his election to the U.S. Senate four years later. Moore went to federal prison for tax evasion.

The astronomical increases in gubernatorial spending helped drive up the price of other state campaigns. In 1976, candidates spent a total of $154,953 on all races for the Senate. By 1986 the total had soared to $1.5 million.

Concerned that wealthy and well-funded candidates were dominating elections, a diverse cross-section of groups formed a coalition called the Campaign Finance Task Force to study the problem. The coalition — which included the state Chamber of Commerce, the League of Women Voters, and Common Cause — found that the demands of fundraising limit the number of people who can afford to run for office, limit the time candidates have for voters, and influence their decisions once they are elected.

“The Task Force believes that limiting or controlling campaign expenditures in West Virginia would help curb or eliminate many of these problems,” the group concluded in its final report.

The most effective way to curb spending, the Task Force noted, would be to impose mandatory limits on campaigns. But such ceilings might violate Buckley v. Valeo, a 1976 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that invalidated mandatory limits in federal campaigns. Fearing that state limits would also be struck down as unconstitutional, the Task Force recommended that West Virginia pressure candidates to accept voluntary limits and develop a system of public financing to reduce the sway of private money.

The following year, Secretary of State Hechler used the recommendation to draft the Code of Fair Campaign Practices, a voluntary set of ethics guidelines and spending limits for state candidates. The Code puts a ceiling of $1 million on campaigns for governor, $25,000 for Senate and circuit judge, and $12,500 for the House.

Rocking the Boat

At first, many observers were skeptical of the Code. After all, the secretary of state had no way to enforce limits on campaign expenditures — all he could do was ask candidates to spend less and play fair.

Nevertheless, candidates began signing the Code voluntarily. The year it was introduced, 72 percent of all winning House candidates and 82 percent of all winning Senate candidates abided by the guidelines. Total spending for Senate races dropped for the first time in state history, from $1.5 million in 1986 to $899,881 in 1988.

Hechler was thrilled by the initial acceptance of the Code. “There came a sweet smell of success when the cost of campaigning came down even a bit,” he says. Hechler and others say a major reason for the success was public pressure on candidates to sign the pledge. Public interest groups and the media wholeheartedly supported the reform effort.

“One of the most important factors in reducing spending is calling attention to the problem,” says John Barrett, director of West Virginia Common Cause. “We hammer away at the candidates who spend lavishly, and so do the media. We embarrass politicians.”

David Grubb was one politician who wasn’t embarrassed. As director of the West Virginia Citizen Action Group, Grubb had played a key role on the task force that recommended spending limits. Elected to the House of Delegates in 1988, he went to work to convince his fellow legislators to clean up campaign finances.

Democratic Cops

By Mary Lee Kerr

Activists in West Virginia aren’t alone in their efforts to uproot the power of campaign contributors. Elsewhere in the South, community organizers are working to involve more citizens in politics — countering big money with an even bigger vision of democracy.

One of the most successful campaigns to rekindle grassroots control of the political process has been waged in San Antonio, Texas. Over the past 18 years, community organizers in the city have succeeded in uniting low-income residents of all races in a group called COPS — Communities Organized for Public Service. Working together, residents have commanded more attention of local officials and more control over public resources.

Since its founding in 1974, COPS has helped channel more than $750 million into inner-city neighborhoods for new housing, streets, sidewalks, sewers, parks, and libraries. Perhaps more important, it has helped overcome a sense of powerlessness among citizens, showing them that government can be redirected to serve community needs.

“COPS has been able to wrest itself a share of the political pie," noted The Texas Observer. "It has changed the political equation in San Antonio."

Beatrice Gallego helped found the group and served as its second president. When the organization began, the city was deeply divided along economic lines. Black, white, and Hispanic communities all suffered from poor housing, low wages, and bad schools.

“Our first fight was for dignity—to get better streets and drainage to keep our families from walking in the mud," Gallego recalls. “Our second fight was for respect and power. Through voter education and registration, we ensured that our voice was heard. We filled city hall with thousands of COPS members."

Gallego calls the third battle “the toughest fight of all. We challenged the business and special interest notion that San Antonio could be sold as a low-wage town." COPS fought for job training and quality education —what Gallego calls “the right and priority of every Texan."

Organizers say COPS was able to convince poor residents to unite across racial lines because its goals grow out of the values and basic needs of its members. “One of the most important and powerful organizing tools is self-interest,” says organizer Ernie Cortes Jr. “You build power by organizing people around their interests. You build it by drawing people out of their passivity, out of their alienation and their bitterness.”

Empowerment has paid off. COPS convinced the city to spend $10 million to finance affordable housing, formed an Education Partnership program to give jobs and scholarships to students from poor communities, and helped win passage of a bond issue to improve streets and sewers.

COPS succeeds because it does more than mobilize voters — it also mobilizes public resources. “It takes organized people and organized money,” says Cortes. Because the group has a powerful constituency of nearly 100,000 members, public officials regularly seek its input on crucial policy decisions involving millions of dollars of tax money.

COPS also teaches people “how to lift the veil of secrecy that shrouded public decision-making,” Cortes says. Along with voter education programs, the group holds “accountability nights” where candidates sit and listen to members speak about local issues — a switch for politicians used to doing the talking.

The success of COPS has inspired similar organizations in nearly every major city in Texas. Working through a parent group called the Texas Industrial Areas Foundation Network, citizens have formed organizations in Houston, Fort Worth, Austin, El Paso, the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Fort Bend County, Victoria, and the Eagle Pass area. New organizations are currently being formed in Dallas and Port Arthur.

Such power redirects democracy to the grassroots, replacing the influence of big money with the values of ordinary people. “Today San Antonio is one of the most open cities in America,” Cortes says. “It is a place where the values of pluralism, family, and freedom of speech have become a concrete reality."

Teaming up with Speaker of the House Chuck Chambers, Grubb co-sponsored a bill to officially endorse the Code of Fair Campaign Practices by “codifying” it — formally placing it on the state books and requiring election officials to give every candidate an opportunity to sign it. The bill also limited PAC contributions, as well as the amount candidates could raise once in office to repay personal campaign loans.

Chambers called the bill long overdue. “If we don’t start changing the way we finance campaigns, politics are going to become even more of a rich person’s playground than they already are,” he says. The bill passed in the House by an overwhelming majority this year, but it died in the Senate Judiciary Committee without ever coming to a vote in the full Senate. Judiciary chair Jim Humphreys told reporters that committee members considered it unconstitutional to restrict campaign loans — but Secretary of State Hechler offered another explanation for the resistance to the reforms.

“Many of these senators were elected under the current system, and they don’t want to rock the boat,” says Hechler. “The truth is, many of them might want to run for governor someday, and they don’t want to be embarrassed by having to exceed a spending limit.”

Bare Bones Budget

It has been four years since Hechler first pushed candidates to sign the Code of Fair Campaign Practices, and there is already evidence that it is working. Contrary to trends in other states, spending on legislative races in West Virginia has slowed since the Code was introduced. Between 1986 and 1990, the average cost of winning a Senate campaign declined from $44,237 to $24,914. The average cost of a House victory dipped from $8,666 to $7,965.

David Grubb knows first-hand that candidates can limit their spending and still win elections: He won his primary bid for the state Senate in May, even though he voluntarily kept his campaign bills to $25,000. The hardest part of abiding by the limit, he says, was learning to allocate the contributions he did receive.

“It was very difficult at times on a bare bones budget,” says Grubb, sitting at his dining room table cluttered with campaign materials. “I really had to look at the cost effectiveness of everything I did. For example, I could only afford four TV ads during the whole campaign, and I had to choose them by price. It was a real struggle.”

Grubb won the primary even though his challenger, Barbara Hatfield, refused to sign the Code and reportedly spent $31,000 before the final two weeks of the campaign. Even though Hatfield is known for her good record on consumer and environmental issues, much of her money came from oil and gas conglomerates, coal operators, and other industry groups eager to defeat Grubb, a long-time foe of big business. The big contributions enabled Hatfield to concentrate her spending on an expensive TV and radio blitz blasting Grubb.

“Dave has got a long record in politics,” says Hatfield, a registered nurse who served in the House from 1984 to 1990. “I needed that money to get my message across.”

But this time, money wasn’t enough. Relying on direct mail and a door-to-door campaign to counter Hatfield’s industry-financed ads, Grubb won by 2,000 votes. “I’m relieved,” he says. “It was a tough campaign — but this proves you can withstand negative ads and still win.”

The Gold Dome

Despite the success of the Code at lowering spending on legislative races, campaigns for governor in West Virginia remain as opulent as the gold-plated dome of the State Capitol.

In the May primary, Governor Gaston Caperton showed no interest in joining the movement to limit campaign spending. Caperton — who spent $5 million to defeat Arch Moore in 1988 — ignored a public plea from the secretary of state to sign the Code of Fair Campaign Practices and limit his campaign spending.

“The state needs both your example and your leadership if it is ever going to get a handle on campaign spending,” Hechler wrote the governor in the spring. “I consider it my duty as secretary of state to continue to urge you, both privately and publicly, to set a limit in the primary election of $1 million on your campaign for governor.” But Caperton decided to set a different example. “We’re going to be aggressive in presenting our message to the people, whether the cost is $1 million or more,” press secretary George Manahan told reporters. “We’re going to do whatever it takes.” Although the final tallies from the May primary are not in, the secretary of state reports that Caperton spent “well over a million dollars” to keep his residence in the governor’s mansion. Big spending helped the incumbent beat off a grassroots challenge from state Senator Charlotte Pritt, a coal miner’s daughter who pulled 35 percent of the vote despite her low-budget campaign.

The win-at-all-costs attitude means that West Virginia — wracked by poverty and high unemployment — will witness two millionaires facing off in the November election for governor. Caperton, who comes from a wealthy coal and insurance family, will be challenged by Republican Agriculture Commissioner Cleve Benedict, a “gentleman farmer” who is heir to much of the Procter and Gamble fortune.

“One millionaire running against another in the state of West Virginia is obscene,” Pritt told The Nation. “These people have never had to worry about health care, about having enough to eat, about getting a job that pays enough to make ends meet. They have no idea how most West Virginians live, yet they’re trying to lead the state.”

Here Spend the Judge

Many judicial candidates have also rejected efforts to lower their spending. In the May primary, Kanawha County Circuit Judge John Hey spent $61,803 — more than twice the limit specified in the Code — to defeat liberal challenger Mike Kelly. Kelly voluntarily abided by the Code, spending $20,946 on his campaign.

Hey refused to sign the Code “because he knew that dozens of lawyers who come before him in court would give him money,” charged an editorial in The Charleston Gazette, the major state newspaper. “In contested races, some lawyers give to both sides, so they’ll be on friendly terms with whoever is elected. It smacks of coercion, a shakedown.”

Despite such politics as usual, the secretary of state and other reform advocates remain encouraged by their success at bringing down spending on legislative races in West Virginia. Hechler says he is eager to enact mandatory limits that will challenge Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court ruling that protects big campaign spending.

“Campaign spending has skyrocketed since the Court ruled on the issue in 1976,” Hechler says. “It’s absolutely necessary to reverse that decision to protect free speech for the average person who can’t afford to enter the political arena. Hell’s bells, somebody’s got to challenge that ruling.”

David Grubb and reformers like John Barrett of Common Cause are taking a different approach. They plan to continue to fight for a system of public financing in West Virginia — and they plan to step up their grassroots organizing before the November election. The goal, Grubb says, is to use primary victories like his to convince disenchanted citizens they can make a difference.

“My victory says you can adhere to a spending limit and still win,” he says. “I hope it will help change the public perception that only the privileged and powerful count in politics. A limit on campaign spending allows people of average means to throw their hats into the political ring on an equal basis.”

Tags

Susan Leffler

Susan Leffler is a freelance writer in Charleston, West Virginia. (1992)