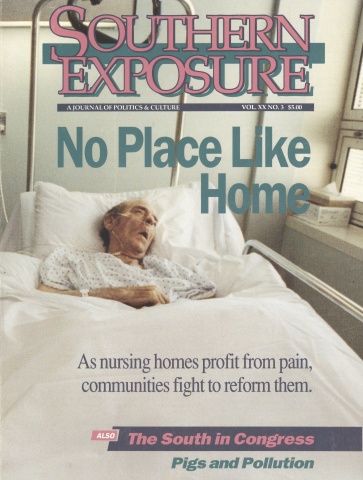

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 3, "No Place Like Home." Find more from that issue here.

New York, N.Y. — The most famous Southerner making the rounds at the Democratic National Convention this summer was not Bill Clinton or Al Gore. Nor was it Jesse Jackson, or even Jimmy Carter.

It was Bubba.

“Excuse me,” said a local news reporter, stopping a late-afternoon commuter in front of Madison Square Garden. “The Democrats are about to nominate a double-Bubba presidential ticket. I was wondering if that will make you less likely to vote for them.”

No matter where you turned, it seemed someone was invoking the tobacco-spittin’, pickup-drivin’, coon dog-raisin’ white man of Southern iconology. To some people, Bill Clinton and Al Gore, two Ivy Leaguers who would look exceedingly silly in overalls, were themselves Bubba incarnate. In These Times, a national newsweekly based in Chicago, referred to the candidates as the “all-bubba ticket” and offered this analysis of the convention: “Democratic strategists apparently believe that African-Americans will have little choice but to go with bubba boomers (baby-booming bubbas?) in the November election.”

But Bubba wasn’t just creeping into the news reports of the 15,000 journalists who converged on New York for the convention in July. Even before the convention started, the mythical man seemed to find his way into Clinton’s central command post. There, he sat in the comer, quietly reminding the campaign strategists that white Southerners don’t cotton to candidates who embrace blacks and labor unions. If the Democrats wanted to recapture Dixie, he advised, the party would have to distance itself from Jesse Jackson and get tough on welfare recipients. A strong stand for capital punishment, accompanied by the execution of an Arkansas man with the mental capacity of a child, couldn’t hurt either.

Someone had evidently forgotten to tell Clinton that during the 1988 Democratic primaries, it was Jesse Jackson who carried the South.

Southern Platform

A small crowd pressed around Bob Fitrakis in the lobby of the Ramada Hotel, across from Madison Square Garden. Fitrakis, a Jerry Brown supporter from Ohio, had sat on the committee that drafted the Democratic Party platform. And he was angry at what he viewed as meat-fisted efforts to “Southernize” the convention.

In particular, Fitrakis was protesting the way the Clinton campaign had stifled a debate on the death penalty. During the platform committee meetings, Brown supporters had proposed more progressive language on 22 issues. Most lacked enough support for a full airing, and the Clinton forces summarily quashed them. But the anti-death-penalty plank had gathered enough signatures for a discussion on the convention floor. Undaunted by this groundswell of democratic sentiment, Clinton strategists simply used a loophole in the rules to squash the debate.

“This is the Southernization of the platform,” Fitrakis griped. “There was a strategy developed by the Democratic Leadership Council and the mainstream caucus that if we give in to the Reagan-Bush agenda and back away from social justice issues, environmental issues, labor-support issues, we’ll win.”

To some degree, Fitrakis was overstating his case. While the Southern-dominated Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) from which Clinton hails does embrace political “centrism,” the platform hardly rubberstamps the Reagan-Bush agenda. It comes out for abortion rights, child care, and lesbian and gay rights. It supports collective bargaining, and talks about empowering workers to hold their bosses more accountable for workplace dangers. It calls for higher taxes on the rich, a departure from Michael Dukakis’ timid strategy of four years ago. And it criticizes the GOP for taking a lenient approach to white-collar crime, vowing to “ferret out and punish those who betray the public trust, rig financial markets, misuse their depositors’ money or swindle their customers.” Still, the Clinton forces resisted efforts to strengthen platform language in areas like environmental protection, worker rights, and campaign finances. And the document departs from traditional Democratic platforms in important ways. It embraces private enterprise and entrepreneurship with unusual fervor, and it criticizes the “big-government theory that says we can hamstring business and tax and spend our way to prosperity.”

What’s more, in the weeks leading up to the convention, Clinton distanced himself from organized labor, as well as from activist blacks like Jackson. Besides his surprise attack on rapper Sister Souljah at a gathering of the Rainbow Coalition — a clear signal to white voters that Clinton was willing to publicly insult black leaders — the candidate warned the United Auto Workers that he would support a free-trade agreement with Mexico, which the union opposes.

Bashing unions and African-Americans were all part of the plan to woo white voters who have forsaken the party in recent presidential elections. “Clinton took the first step when he stood up to Jackson,” Texas Land Commissioner Gary Mauro told Business Week.

Perhaps the most subtle signal from Clinton has been his talk of the “forgotten” middle class. For more conservative voters, that emphasis signals a welcome departure from the Democratic Party’s tradition as an advocate for the poor (and, by extension, blacks). Al From, director of the DLC, says the political shift was spurred by the party’s loss of six of the past seven presidential elections. “Losing has a way of focusing the politicians,” From told reporters during the convention. “Liberalism lost favor when we quit being a party of prosperity and growth.”

It’s clear that much of this strategy was aimed at Southern voters. Even the layout of the convention at Madison Square Garden suggested the importance of the South this fall. While Arkansas delegates received the best seats at the convention, they shared the most direct view of the podium with delegates from Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

But the Clinton camp might well be misreading the South if it thinks the correct Southern strategy entails moving sharply to the right. Many white Democrats have fled the party in the past 12 years, casting their votes for Ronald Reagan and George Bush. Those Reagan Democrats — the Bubbas — are DLC’s prime targets.

But the South can also exhibit a strong populist streak at the polls. Florida voters elected Governor Lawton Chiles on the strength of his anti-big business message. Terry Sanford of North Carolina won his U.S. Senate seat only after focusing on his opponent’s country-club style and political views. In Texas, voters supported Governor Ann Richards and Railroad Commissioner Lena Guerrero, both of whom ran as progressives. Throughout the region, Southerners pulled for Jesse Jackson in 1988 and repudiated white supremacist David Duke in 1992.

The South has a strong black electorate, particularly in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina. The region also has a growing number of Northern transplants, as well as millions of adults who don’t usually vote. If Clinton wants to carry the South, he cannot take any of those votes for granted.

Even Bubba himself might not be looking for a conservative message with race-baiting undertones. Jerry Brown carried Michigan and Connecticut on the strength of white working-class voters who appreciated his message of putting economic power back in the hands of average citizens. Indeed, many Reagan Democrats fled the party not because of its social liberalism, but because it consistently failed to formulate an economic message that seemed relevant to their lives. In the absence of that economic message, some white working-class voters have been drawn to the racism and moral conservatism that the GOP offers.

Party On

In pushing the party to the right, Clinton did more than carefully script the political message at the convention: He also worked hard to silence any opposing voices. Besides his efforts to muscle Brown out of the platform debate, there were more subtle tactics. The seating arrangement was designed to keep Brown delegates out of the spotlight, while more radical speakers like Brown and Jackson were kept out of prime time.

The get-tough-on-dissidents stance was designed in part to impress big business. “It’s unbelievable,” Democratic National Committee treasurer Robert Matsui told the National Journal. Corporate convention sponsors are “up on the fact that Clinton and Gore were telling Jerry Brown, ‘Look, you endorse and then maybe you can speak.’ We are not pandering to these little special-interest groups running around. Usually we spend hours and hours negotiating with these guys and then cave in. This time we are just not going to cave in.”

Fitrakis, the Brown supporter, had a more bitter take on the refusal to negotiate. “What they want is a coronation,” he said.

In the North Carolina delegation, Clinton delegates received their orders at a daily breakfast. There was no debate over the proposed platform amendments or rule changes. Clinton delegates were simply told how to vote.

One morning, Clinton’s chief North Carolina “whip,” Ed Smith of Raleigh, announced that Brown had proposed two amendments to the convention rules. Smith never told his fellow Tar Heels what the amendments would have done — namely, create a commission to study issues such as campaign finances and low voter enthusiasm. “These need to be voted down,” Smith simply informed delegates. “Hence, our votes must fall in line accordingly. We must vote these down as efficiently as we can.”

When the full convention debated Brown’s proposed rules changes later that day, North Carolina delegates ignored the discussion and bounced a large beach ball in the air. The sizable Brown contingent from Ohio, which sat immediately behind North Carolina, was infuriated. “This is not a beach party,” grumbled Bob Sholis, a Brown delegate from Columbus. “It’s a political party.” Perhaps no North Carolinian felt the burden of the forced unity more intensely than Melba Melton of Rowan County. As the state’s only Brown delegate, Melton could barely hold up a placard without someone trying to block it from the TV cameras with a Clinton sign. A couple of times, other delegates shouted at her, telling her to take down her sign.

Melton couldn’t understand why caucus meetings consisted of pep talks rather than political discussions. “There’s serious work to be done,” she said. “Most of us are here for a big party. We should be reviewing the platform. We should be having representatives from both candidates to speak. We should be debating the issues, how we can bring even dissident voices into the fold, because we will need every Democrat we can get to defeat George Bush in the fall.”

Being There

While Clinton kept dissenters at bay, he managed to avoid giving the convention a conservative, exclusionary tone. To the contrary, the gathering had a warm, inclusive feel — enough to make the 52 percent of the delegates who told pollsters that they considered themselves liberal feel welcome. For four days, speakers like New York Governor Mario Cuomo — along with scores of lesser-known Democrats — extolled the Democratic Party’s traditional values of social welfare and civil rights. Georgia Governor Zell Miller hearkened back to the party’s New Deal heyday when he described growing up with his single mother during the Depression: “Franklin Roosevelt... replaced generations of neglect with a whirlwind of activity, bringing to our little valley a very welcome supply of God’s most precious commodity: hope.”

And Jackson brought that vision into the ’90s, describing his $1 trillion plan to rebuild America. In a speech with themes ranging from Haitian immigration to Middle East peace, Jackson touched Southern hearts by invoking last year’s fatal fire at the Imperial Food Products chicken plant in Hamlet, North Carolina.

“If we keep Hamlet in our hearts and before our eyes,” he said, “we will act to empower working people. We will protect the right to organize and strike. We will empower workers to enforce health and safety laws. We will provide a national healthcare system, a minimum wage sufficient to bring workers out of poverty, paid parental leave. We must build a movement for economic justice across the land.”

That’s a far cry from the party platform, which calls for labor to join business “in cooperative efforts to increase productivity, flexibility, and quality.”

Even Clinton’s acceptance speech, with its promise to “end welfare as we know it,” had enough liberal elements in it to please much of the party’s left wing. As he delivered the hour-long address, whites and blacks alike — often people with opposing political views — cheered and cried together. Not since Jimmy Carter won the nomination in 1976 have delegates at a Democratic convention stood together so firmly. As much as anything, that unity testifies to the marketing genius of the Clinton campaign — how adroitly the party has packaged its candidate this year.

To progressives, Clinton was heir to the visions of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. The slick, Hollywood film that introduced Clinton to the convention even contained eerie, black-and-white footage of the candidate as a fresh-faced youth from Hope, Arkansas eagerly shaking hands with President John Kennedy during a reception in the Rose Garden. Here, the film suggested, was a man who would struggle Even Bubba himself might not be looking for a conservative message with race baiting undertones. for an America that welcomes people regardless of race, family status, or disability. In his acceptance speech, Clinton proposed taxing the rich and even broached the topic of discrimination against lesbians and gay men.

To conservatives, however, he was a man who would create a 100,000-strong national police corps and make welfare recipients take responsibility for their lives. “We will say to those on welfare: You will have... the opportunity through training and education, through child care and medical coverage, to liberate yourselves,” Clinton said in his speech. “But then, when you can, you must work, because welfare should be a second chance, not a way of life.”

It seemed a little like Being There, the Jerzy Kosinski novel about the simple-minded gardener who became president — because he was a blank slate on which each person could write his or her own prescription for the future. Only Clinton is no simpleton; he’s a shrewd politician who knows how to appeal to all people by intentionally becoming a blank slate. Each Clinton delegate sketched his or her own dreams and aspirations on the man who won the Democratic nomination.

“Sometimes I think he’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” said Mike Nelson, a gay delegate from Carrboro, North Carolina. “I think he’s a liberal.”

Indeed, while Clinton was vowing to “put people first,” he was also taking advice from lobbyists for Toyota, Occidental Petroleum, the National Association of Manufacturers, and other corporate causes. “They don’t think this ticket is hostile,” said Democratic treasurer Robert Matsui, adding that Clinton was gaining support from the energy and defense industries.

The only Democrats who didn’t see Clinton as their party’s savior were the ones who best understand how corporate interests have corroded the democratic system. “The Clinton strategy does not call for a genuine campaign against the entrenched economic interests that hold sway over both parties,” wrote the Texas Observer after the convention. “Therefore, Clinton cannot be presumed to be seriously interested in the deterioration of American democracy.”

Even so, delegates like Bonnie Moore, a Brown supporter from Austin, Texas, conceded that Clinton would do more than President Bush to wrest political power from mammoth corporations that give millions in campaign contributions. “I’m certain that Clinton, if he’s elected, will not veto the Campaign Reform Act,” she told the Observer. “Any Republican will veto it.”

Voting for Ourselves

Such anybody-but-Bush sentiment may indicate how Clinton can win this November, despite his misguided appeal to the “Bubba” vote and his failure to address fundamental economic realities. After all, he is the first baby-boomer candidate of either party to run during a prolonged recession accompanied by a fierce anti-incumbent backlash. In the end, the central issue for many voters — as for many delegates at the convention — may have more to do with where Clinton stands in relation to President Bush than with whether he is a liberal or a centrist.

Stella Adams attended the convention as an uncommitted delegate. “I came here to make sure that issues affecting African Americans and women were given priority by our delegation and by the convention itself,” said Adams, a city employee from Durham, North Carolina.

At first, Adams felt ambivalent about the Clinton-Gore ticket, with its eschewing of Jackson and its emphasis on the middle class. “I think African Americans are comfortable with them as individuals, but we need reassurance that our needs are going to be addressed and really on the front burner,” she said. “Right now, we don’t have that confidence.”

Yet over the course of the week, the convention magic worked on Adams. She came to believe that the two Southern white men would not only address the issues she cared about — health care, education, and economic opportunity for blacks — but could carry North Carolina and the nation. “I’ve come a long way,” Adams said the day Clinton accepted the nomination.

But what about Clinton’s efforts to distance himself from Jesse Jackson and court the conservative white vote?

“When you have a president who doesn’t have a clue to what’s going on anywhere in the United States of America outside golf clubs and tennis courts, we don’t have much choice,” Adams said. “If we want a chance, we’ve got to vote for Clinton and Gore, because that is the only opportunity we have.

“African Americans cannot afford to be emotional,” she continued. “We have to be practical because our community is at stake. Our children are at stake. We’ve got to have someone in office who will rebuild inner cities, and who’s going to implement programs that will effect lifestyle changes in our communities, that will educate our kids, provide them with job training, provide them with health care. If we want that chance, then we have to be practical. That means we must get out, actively work for, and show up en masse at the polls — not for Clinton and Gore, but for ourselves.”

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)