This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

Several months ago, several Native Americans joined an archaeologist and a clergyman near a construction site in Jacksonville, Florida. Excavations for the new Holy Spirit Catholic Church had disturbed the bones of 23 Indians, thought to be the victims of a 16th-century epidemic, and the four had come together to reconsecrate the burial ground.

Harvey Silver Fox Mette, the white-haired chairman of the Commission for Native Americans of the Diocese of St. Augustine, made offerings of corn and tobacco. After burning sweetgrass for incense, he lit a sacred pipe and passed it to each participant. “Creator, help the spirits of all generations buried in this site to understand,” Silver Fox intoned. “We are here to honor this place and honor the dead.”

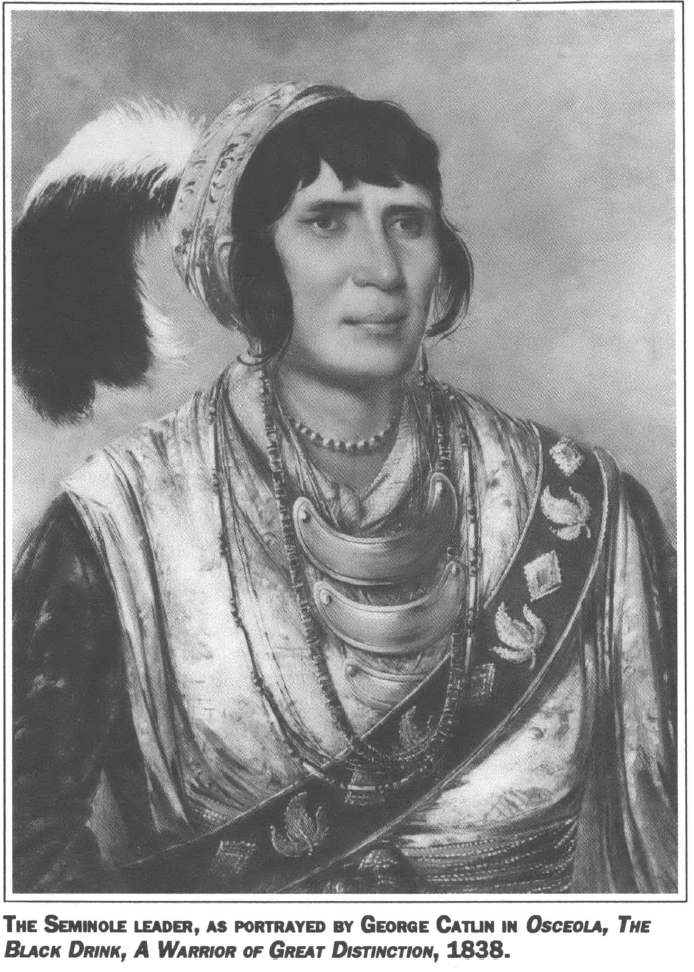

Southern Indians, living and deceased, have not always been treated with such respect. When the Seminole chief Osceola died in a South Carolina prison in 1839, for instance, the attending physician felt no qualms about removing the Indian leader’s head and taking the skull home to St. Augustine as a souvenir.

Today, museums across the country are reconsidering their position regarding human remains and sacred artifacts scavenged from Indian sites by earlier generations. Those planning the new National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. are taking special pains to design a facility that treats the Native American past with proper regard.

But 500 years after the arrival of Columbus, most Americans remain as oblivious as ever to Native American cultures, past and present. When controversy erupted last year over the names of two Southern sports teams — the Washington Redskins and the Atlanta Braves —most spectators knew more about split ends and stolen bases than about the history of the original Southerners.

“White people rarely concerned themselves with Indian matters,” concludes the central character in Mean Spirit, a recent novel by the Chickasaw poet and essayist Linda Hogan. “Indians were a shadow people, living almost invisibly on the fringes.”

Invisibility is nothing new in the South. A generation ago, black Southerners, forced to sit at the back of the bus on the way to work, had no seat at all when it came to occupying a place in the region’s past. Black history was distorted and ignored. A few African-Americans knew a great deal about their ancestors, but the white majority was cloaked in a blanket of ignorance.

It took scholars decades to uncover the Afro-American past and reveal the story of black struggle in the region. Yet Southern historians are only now beginning to devote their attention to the Native American past — even though Indian history is just as central to the real South, and just as obscured by disregard and misinformation.

As the study of Southern Indian history intensifies, it is fast becoming one of the most exciting fields of current research and writing. Unfortunately, generations of silence and prejudice have allowed important oral history, as well as written records and other artifacts, to disappear forever. Nevertheless, much remains within reach for making the saga of Native Southerners more visible — a story that lives on among the nearly 300,000 Indians who still inhabit the region.

Follow the Thread

Last year I expressed some of these thoughts to Eric Bates, the editor of Southern Exposure, and enthusiastically described the remarkable number of new books and articles dealing with the long and circuitous past of Southern Indians. I remembered that his publication had devoted a special edition to Indian issues in 1985, and I had worked with him before to publish articles on the Native American heritage of the region.

We talked at length about whether the magazine might somehow go beyond the political bantering and journalistic hoopla that has marked the Columbus quincentennial. “Would it be possible to follow the thread of Southern Indian history from Columbus to the present?” Eric asked me. “Easier than it would have been a generation or so ago,” I answered evasively.

“Look,” he continued. “Everybody seems to be telling us what happened in 1492, and everyone is arguing about where we stand now. But no one ever talks about how these worlds are connected to one another, about what happened in between then and now. Most of us have heard of Pocahontas and Osceola, but Indian Southerners still seem unconnected to the rest of the region’s history. Isn’t it all part of a single story?”

“Absolutely,” I replied.

His next question was tougher. “Can you write about all of it in 30 pages?”

“Absolutely not,” I answered. “It’s too big a subject.”

But the more I thought about it, the more the idea excited me. “I’ll be glad to sketch out a broad overview,” I finally agreed. “But only if we find a way to make the story available to public schools.” After all, I explained, we historians are just beginning to explore this part of Southern history. The people who will eventually write it properly are still in high school.

Was the idea worthwhile? Luckily, the North Carolina Humanities Council and the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation thought so. They gave us a grant to prepare a special report and to work with teachers and libraries to develop a supplementary packet of classroom material. With their encouragement, we assembled an advisory panel of first-rate scholars — Charles Hudson, Jane Landers, James Merrell, Theda Perdue, and Daniel Usner — all of whom have written about Indians in the South.

I taped George Catlin’s portrait of Osceola above my desk and went to work. If I could not return the Seminole leader’s head to his body in any literal way, perhaps I could restore some completeness to the dismembered story of Southern Indian history itself. It was worth a try, and I jumped at the opportunity.

Since I wanted to survey the whole story of Native American history, I knew I could not begin in 1492. The world Columbus had encountered by mistake, though new to him, was a very old world indeed. So I moved the starting point of the story back more than 12,000 years, to the origins of Native American culture in the region.

After 1492,1 wanted to give each century equal weight. I knew I would have neither the space nor the background to explore the unique history and culture of every Indian group in detail. I also knew it would be impossible to pursue the story of what has happened to Southern Indians who were removed to Oklahoma 150 years ago. At least not this time. Still, if I could sketch the forest in 30 pages, maybe readers would be inspired to examine individual trees on their own.

I was fortunate to have the support of dozens of people who helped to strengthen “When Old Worlds Meet.” I join with the editor in thanking the N.C. Humanities Council, the Mary Duke Biddle Foundation, and our supportive panel of advisors, as well as Duane King, Sharon Dean, and John Colonghi at the National Museum of the American Indian.

Eric Bates and Claudio Saunt did wonders to give shape to the project. I would also like to thank Larry Chavis, Jim Crisp, Stephen Davis, Lil Fenn, John Hope Franklin, Thomas Hatley, Woody Holton, David Kleit, Roger Manley, Joel Martin, Deborah Montgomerie, Jon Sensbach, Maude Wahlman, Trawick Ward, Emily Warner, Greg Waselkov, Susan Yarnell, and members of the Triangle Area Native American Studies Workshop.

Even with the help of all these people, exploring so many centuries of Native American history has proven a humbling experience. In writing the six articles that follow, I was constantly aware that each paragraph represents only a brief glimpse of a much wider subject. No matter what the topic or the era, much more is known than I could include here — and far more remains to be learned by the next generation.

Tags

Peter H. Wood

Peter H. Wood is an emeritus professor of history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He is co-author of the U.S. history survey text, "Created Equal," now in its fifth edition.