A War of Fire & Blood: 1492-1592

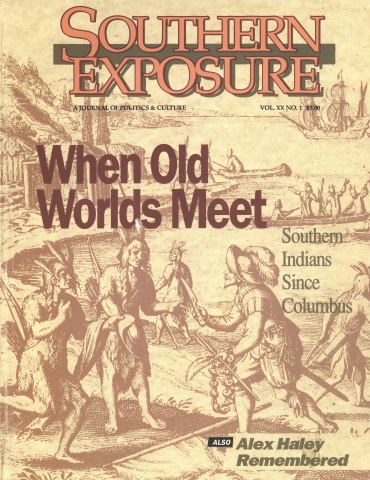

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

In early October 1492, after more than two full months at sea, Christopher Columbus still had not sighted land. By sailing due west from Spain at 28 degrees north latitude, he had hoped to reach Japan and then China. He knew the earth was round, but he had drastically underestimated its circumference, leading him to believe he was now close to his destination.

On October 7, advised by his pilot that signs suggested land to the southwest, he altered course in that direction. It was a fateful decision. Had he continued at 28 degrees for another week or two, his small fleet would have landed south of what is now Cape Canaveral, Florida, altering the course of Southern history.

Such was not to be the case. Columbus came ashore on a tiny island in the Bahamas, and in three return voyages he pressed south and west into the Caribbean and along the coast of Central and South America. He continued to believe until his death in 1506 that he had reached the islands off the Asian coast known as the Indies, and he insisted on calling the inhabitants “Indians.”

The name stuck, and as Europeans encountered and described Native American peoples over the coming centuries the term took on a life and meaning of its own. No name has ever been more thoroughly misplaced. But any unifying phrase posed problems, for tremendous diversity characterized the long-time residents of the Americas.

Nothing illustrates this diversity better than language. By 1492, there may have been as many as 2,000 different languages spoken in the Americas, evolving slowly and persistently from common roots during millennia of migration, isolation, and change. In the onslaught of war and disease initiated by Columbus’s first voyage, many languages soon disappeared entirely without ever being recorded or preserved. Others, such as Cherokee and Choctaw in the South, have endured to this day.

Over the past century, by comparing words and structures in surviving Indian tongues, linguists have identified 15 or 20 large “families” of languages that each share a common source. Of the language groups prominent in the South 500 years ago, by far the largest was Muskogean, which gave rise to the speech of Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and Choctaws and Chickasaws in Mississippi. The Cherokees in Southern Appalachia and the Tuscaroras in Eastern North Carolina shared an Iroquoian language stock; the neighboring Catawbas spoke a language distantly related to Siouan; while the coastal tribes near Chesapeake Bay were Algonquian speakers. “The languages which belonged to these families,” explains Charles Hudson of the University of Georgia, “were as different from each other as English is from Chinese.”

Southern Living

The first Southerners also differed from each other physically. Even if early explorers lumped them together as “Indians,” not all Americans looked the same. Giovanni da Verrazzano, cruising along the Carolina coast for the French in 1524 in hopes of discovering a passage to the Pacific, noted that the local residents were “rather broad in the face: but not all, for we saw many with angular faces.” Early Europeans noted that many Southerners appeared taller than themselves and varied in skin color from olive to dark-copper. Some inhabitants tattooed their bodies with elaborate designs, while others bound their infants to cradle boards during their first year to flatten their skulls permanently in a manner considered handsome.

The complex geography of the region also prompted variations in Southern living. Existence in the coastal low country, with its long growing season, mild temperatures, and abundant water resources, contrasted with daily life in the cooler piedmont and the more heavily wooded mountains, but the differences usually represented variations on a common theme: easier fishing, larger gardens, or a longer hunting season. “By the time Europeans arrived at the dawn of the 16th century,” says Professor Tim Silver of Appalachian State University, “all Indians in the region practiced four basic types of subsistence. They hunted game animals, fished the streams and rivers, planted and harvested crops, and gathered available wild foods.”

This combination guaranteed long-term prosperity — “for when Sickness, bad Weather, War, or any other ill Accident kept them from Hunting, Fishing, and Fowling,” explained an early European observer, the Indians could rely on corn, peas, beans, “and such Fruits of the Earth as were then in Season.” Likewise, if droughts or floods interrupted the planting cycle, then deer and turkeys, perch and herrings, acorns and hickory nuts became larger sources of food.

The lunar calendars of Southerners reflected the numerous activities that shaped the rhythm of the seasons. For most, the high point of the year was the Green Corn Ceremony in September, accompanying the first full moon after the late corn ripened. During this four-day festival of fasting and renewal, past sins were erased, petty crimes were forgiven, conflicts were set aside, and the sacred fires were extinguished and then rekindled.

The annual cycle between Green Com Ceremonies varied, but the calendar that Europeans found in use among the Natchez illustrates a widespread tradition. The moon “of Maize or the Great Corn,” reports a French visitor, is followed in October by “that of the Turkeys. It is then that this bird comes out of the thick woods... to eat nettle seeds, of which it is very fond.” The November moon “is that of the Bison” and December “that of the Bears,” when the animals are at their fattest. January and February, a lean time of “Cold Meals,” center upon wildfowl and stored nuts. But in March the deer reappear: “The renewal of the year spreads universal joy.”

The next moon, “which corresponds to our month of April, is that of the Strawberries. The women and children collect them in great quantities.” In May come the first ears of spring corn, a time “awaited with impatience,” and in June the watermelons are ready and the fish increase. In July and August, any grapes and mulberries not already eaten by the birds are gathered in, while the corn begins to ripen.

Gold and Slaves

Very few outsiders saw this diverse Southern world during the 16th century, but those who did brought momentous changes, both intentional and unintentional. Those who followed Columbus in the West Indies imposed ruthless punishments and transmitted new diseases that caused massive death. They introduced cattle and hogs that uprooted gardens, and they forced inhabitants to search ceaselessly for gold at the expense of their own subsistence.

Within a generation, the Spanish wiped out nearly all of the several million inhabitants of the islands. “Who of those born in future centuries will believe this?” asked the priest, Bartolome de las Casas. “I myself who am writing this and who saw it and know most about it can hardly believe that such was possible.”

Firmly ensconced in the Caribbean, the Spanish probed relentlessly outward in search of gold, routes to the Pacific, and new workers to replace the dying West Indian population. Juan Ponce de Leon, the wealthy governor of Puerto Rico, was probably searching for slaves rather than a fountain of youth when he first encountered the North American mainland during Easter week—pasqua florida — in 1513. The Spanish gave the peninsula a Latin name, and were soon applying the term La Florida to the entire South as they explored and laid claim to the region.

A generation of voyages along the Atlantic coast would make clear that no easy northern route to the Pacific existed, though hopes of a Northwest Passage to the Orient died hard. In the meantime, a slaving raid to Florida in 1521 proved profitable, and that same year word spread that Hernando Cortez had toppled the wealthy Aztec empire in Mexico.

The success of Cortez, and the bonanza reaped by Francisco Pizarro in 1533 when his army conquered the Inca empire in Peru, fueled hopes among Spanish adventurers that similar wealth could be discovered in North America. Lucus Vasquez de Ayllon led an expedition to the Carolina or Georgia coast in 1526 using Indian hostages as guides. But his translators deserted, the commander died, and the colonizers withdrew in disarray, leaving behind a number of Africans who went to live among the Indians.

The following year, Panfilo de Narvaez landed at Tampa Bay on the Gulf Coast of Florida with a contingent of 600 men. He marched north and west in search of riches, only to be driven out by the Apalachees. Almost all the soldiers died, but Cabeza de Vaca and three companions, including an African, made it back to Mexico City after about a decade in the South and West. De Vaca’s narrative of their harrowing journey described many hardships, including enslavement among Indians on the Texas coast. But his early account of the region encouraged other adventurers to try their luck.

The Spanish Presence

The first and most important arrival was Hernando de Soto, an ambitious conquistador who had fought under Pizarro in Peru. De Soto landed at Tampa Bay in 1539 with an army of 600, including at least four priests, four women, and dozens of enslaved Africans. The invaders brought strange new animals: several hundred horses, a large herd of pigs to provide meat for their journey, and vicious mastiffs and greyhounds — large war dogs trained to attack on command.

Among the Timucuans of northern Florida, de Soto discovered a Spanish survivor of the Narvaez expedition who could serve as a translator. The soldiers headed north from Apalachee into the more populous and centralized Mississippian chiefdoms of the interior. At Cofita-chequi in South Carolina the Spanish stole casks of pearls and took the local chieftainess hostage (see sidebar). In the province of Coosa in north Georgia they arrested the paramount chief, forcing him to join other captives.

By October 1540, frustrated by his failure to find gold, de Soto provoked a chief named Tascalusa by demanding 400 burdeners and 100 women. But Tascalusa and his subjects launched a surprise attack at the town of Mabila, west of what is now Selma, Alabama. The Spaniards, mounted on horseback and wielding lances, wreaked havoc on the Indians, killing at least 2,000 people, including women and children.

The brutal victory proved hollow. “They felt they could never make the Indians come under their yoke and dominion either by force or by trickery,” one chronicler wrote, “for rather than do so, these people would all permit themselves to be slain.” By 1542 de Soto was dead. The next year his 311 survivors withdrew from the region, enslaving 100 Indians to be sold for profit.

In the following generation, Spanish expeditions continued to probe the South. When Tristan de Luna and his men headed north from Pensacola in 1559, they found the interior less populated than before, for “the arrival of the Spaniards in former years had driven the Indians up into the forests,” and epidemic diseases had begun to devastate the population.

Ill-supplied and often hungry, the intruders refused to kill their mounts for food, knowing that the Indians feared horses. Nor did they take time to look for maize. Instead, as one observer wrote, “they asked most diligently where the gold could be found and where the silver, because only for the hopes of this as a dessert had they endured the fasts of the painful journey. Every day little groups of them went searching through the country and they found it all deserted and without news of gold.”

The Spanish not only failed to extract much gold and silver from the South; they actually lost their precious metals to the region. The annual treasure fleet hauling New World booty from Havana to Seville followed the Gulf Stream north along the Florida coast, where storms were frequent. When a ship wrecked, local inhabitants salvaged gold bars and fashioned them into ornaments, while killing or enslaving any Spanish survivors.

Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, sailing to Europe at age 13, was taken captive in such a mishap by the powerful Calusa Indians of southwest Florida. When rescued 17 years later he had mastered four local languages and could serve as a knowledgeable, if embittered, guide. Feeling certain that the region’s militant inhabitants would never make peace or accept Christianity, he advised Spanish officers to deceive and enslave them. “Let the Indians be taken in hand gently, inviting them to peace; then putting them under deck, husbands and wives together, sell them among the Islands,” Fontaneda counseled. “In this way, there could be management of them, and their number become thinned.”

Spanish authorities were anxious to protect the annual treasure fleet and its sailors and to enhance the traffic in Indian slaves. But it was not until 1565, when faced with the prospect of rival French settlements along the Atlantic coast, that they sent Pedro Menendez de Aviles to establish a fort. Menendez destroyed a nearby French colony and built a crude outpost at St. Augustine that would become the first permanent European settlement in North America.

In 1566, in an effort to make peace with the powerful Calusa to the south, Menendez “married” the sister of the cacique, or chief. That same year, just north of the region known as Guale, he set up a post at Santa Elena near present-day Beaufort, South Carolina. From there he sent Captain Juan Pardo inland as far as the Blue Ridge Mountains on two expeditions to explore the territory, plant small garrisons, and introduce Christianity.

Menendez, like other 16th-century Spaniards, was particularly troubled by the open acceptance of homosexuality among Native Americans. Most Indians, including those in the South, recognized androgynous men known as berdaches who dressed as women and accepted non-masculine roles. Far from despising the berdaches, Indians respected them for sharing male and female traits and often granted them important ceremonial status.

But by the era of Columbus, the fear of homosexuality had grown into a powerful force in Christian Europe, and suppression of sexual diversity was especially intense in Spain. When Menendez pressed for permission to expand the slave trade from Florida, he accused the local chiefs of being “infamous people, Sodomites.” He explained to the King of Spain, “it would greatly serve God Our Lord and your Majesty if these same were dead, or given as slaves.” They consider their activities the “natural order of things,” Menendez protested. “It is needful that this should be remedied by permitting that war be made upon them with all rigor, a war of fire and blood, and that those taken alive shall be sold as slaves, removing them from the country and taking them to the neighboring islands, Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico.”

Sudden Death

Policies of “fire and blood” had a devastating effect on nearby tribes, but they ultimately took far fewer lives than the invisible sword of pestilence. Native Americans had lived in an isolated disease environment for thousands of years. Now, with dramatic suddenness, the Spanish were exposing them to new sicknesses for which they had no inherited immunities or preventive treatments. Infectious diseases traveled even more rapidly and widely than the Spanish themselves, wreaking far greater destruction.

The same West Indian smallpox epidemic that helped Cortez conquer Mexico City in 1521, for example, raced throughout North and South America killing untold numbers, for smallpox mortality among unexposed populations can run as high as 90 percent. As historical demographer Henry Dobyns observes, “The most lethal pathogen Europeans introduced to Native Americans, in terms of the total number of casualties, was smallpox.”

If smallpox was the most terrible killer, it was not the only one. Typhoid carried off roughly half the inhabitants of the Gulf Coast barrier islands in 1528; measles swept northward out of New Spain in the 1530s; influenza reduced Southeastern tribes in 1559; and typhus ranged from tidewater Carolina to central and western Florida in 1586.

In the century after the arrival of Columbus, the population throughout the Americas was drastically reduced, fragmenting societies, weakening cultures, and undermining spiritual beliefs. Southerners, who encountered the Spanish first, were among the hardest hit. But the full extent of the dislocation and devastation remains difficult to comprehend. “Aboriginal times ended in North America in 1520 to 1524,” explains Dobyns, “and Native American behavior was thereafter never again totally as it had been prior to the first great smallpox pandemic.”

By the time English colonists landed at Roanoke Island, North Carolina in 1586, most Southern Indians had still never seen a European, but all had felt the impact of transatlantic contact. As more Indians and non-Indians met face-to-face in the coming years, it would be hard for each group to sense or imagine how different the other had been scarcely a century before.

Tags

Peter H. Wood

Peter H. Wood is an emeritus professor of history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He is co-author of the U.S. history survey text, "Created Equal," now in its fifth edition.