Like Snow Before the Sun: 1692-1792

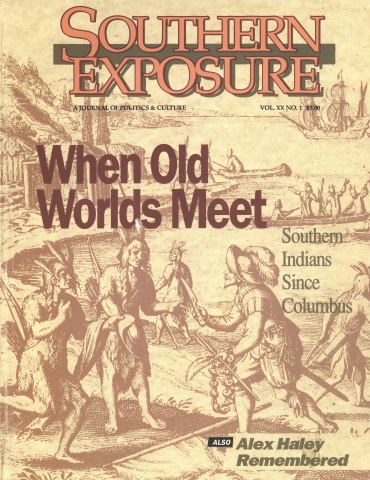

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

My ancestors may not have come over on the Mayflower,” Will Rogers used to quip, “but they met ’em at the boat.” The famous comedian, born in Oklahoma Territory in 1879, used this breezy one-liner to remind his audiences about a complex past they were unwilling to face seriously. Like many modern Native Americans, Rogers combined an Indian and non-Indian heritage. His American roots stretched into the South, where his Cherokee ancestors had already dealt with the disastrous consequences of Spanish exploration by the time the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in 1620. But ongoing relations with Europeans did not begin for the Cherokees and other major groups of the Southern interior, such as the Choctaws and Chickasaws, until the 1690s. The next hundred years would be anything but funny, as seemingly advantageous contact rapidly turned into a desperate struggle for survival, using every tool of diplomacy and warfare.

As always, geography played a crucial role. When the English had first invaded Massachusetts and Virginia, the smaller coastal tribes had been rapidly overwhelmed by disease and defeated in combat. Those who survived were confined to narrow reservations. But further inland, protected by the Appalachian mountains, the Iroquois Confederacy in the North and the Cherokee nation in the South survived the initial onslaught of sickness and conflict, buying time to respond knowledgeably and aggressively to the new threats from overseas. By the beginning of the 18th century, the two interior nations each still numbered more than 30,000.

Seacoast societies were less fortunate. During the 18th century, European powers probed all of the shorelines of North America with increased intensity. The Russians established posts in Alaska; the Spanish built missions in California; the English expanded trading factories in Hudson Bay. In the South, a warm climate and proximity to the booming sugar colonies of the Caribbean intensified competition, and the French now joined the European land grab.

During the 1680s, La Salle had explored the Mississippi River and claimed its huge hinterland for the French monarch, Louis XIV. By 1699 Frenchmen were building an outpost at Biloxi and exploring the lower Mississippi by boat. They found one town of the Houma Indians — a village of 100 huts surrounded by a palisade of cane — ravaged by a smallpox epidemic. Further upriver, where Houma hunting grounds met those of the Bayogoulas, they came across a curious boundary marker on the east bank — “a maypole without branches, reddened, with several heads of fish and bears attached.” This red post, over 30 feet tall, was called Istrouma by the Indians and Baton Rouge by the French. It would one day provide the name and location for the capital of Louisiana.

Dan Usner, a native of Louisiana and professor of Native American history at Cornell University, estimates that roughly 24,000 people occupied the bayous of the Gulf Coast and the Lower Mississippi during the 1680s. A generation later scarcely 7,000 remained. In 1718, as French settlers were laying out the town of New Orleans, a survivor from the Chitimacha tribe described the years of crisis in vivid terms:

“The sun was red, the roads filled with brambles and thorns, the clouds were black, the water was troubled and stained with blood, our women wept unceasingly, our children cried with fright, the game fled far from us, our houses were abandoned, and our fields uncultivated, we all have empty bellies and our bones are visible.”

As the small coastal tribes of Mississippi and Louisiana were being devastated by the sudden arrival of the French, similar groups along the Carolina coast were succumbing to the increasing English presence. “The Small-Pox and Rum have made such a Destruction amongst them,” wrote English traveler John Lawson in 1709, “that, on good grounds, I do believe, there is not the sixth Savage living within two hundred Miles of all our Settlements, as there were fifty Years ago.”

Lawson could have added slavery to his list, for the labor hungry English were paying Indians to deliver up captives taken in war. In 1704, South Carolina raiders and their Creek Indian allies destroyed Apalachee villages in western Florida, taking hundreds of captives to Charleston, where they were enslaved on local plantations or sold into bondage in other English colonies.

Tribes that took part in slave raids, such as the Tuscaroras in North Carolina and the Yamasees in South Carolina, were often pitted against one another, thus dividing resistance to European encroachment. When some Tuscarora villages launched a desperate war against the English in 1711, Yamasee warriors were recruited to crush the rebellion. Many of the defeated Tuscaroras left the South, moving north to join the powerful Iroquois League. Others, who had remained neutral or sided with the English, stayed behind and seized the first opportunity for revenge. In 1715, Tuscaroras helped to suppress a Yamasee uprising that nearly destroyed the South Carolina colony. In 1717 they were granted land on the Roanoke River, and later migrated to Robeson County, North Carolina, where many of their descendants still live.

In Louisiana, meanwhile, the French colony generated limited Indian resistance at first. The colony grew slowly, creating little pressure for land. “There was enough for them and for us,” observed the Natchez elder, Stung Serpent (see sidebar). But as French numbers rose and encroachments increased, tensions mounted. In 1729, ravaged by disease and insulted by a French demand to move their villages, the Natchez nation staged a desperate uprising. They attacked neighboring Fort Rosalie, killing 237 people.

The French retaliated. Employing Choctaw allies in a war of extermination, the newcomers destroyed what had once been the strongest society on the lower Mississippi. More than 400 Natchez captives were taken to New Orleans and sold into slavery in the Caribbean; a few hundred survivors escaped to join the Chickasaws to the north and Creeks to the east.

Deerskins and Diplomats

Groups like the Natchez, Tuscaroras, and Yamasees had once been successful brokers and middlemen between port towns and the interior. But by 1730 they had been violently destroyed or thrust aside by the pressures of increasing trade. The survivors helped to strengthen existing groups or build new ones, such as the Catawbas in Carolina and the Seminoles in Florida.

Further away from the coast, life changed less rapidly and less dramatically. Distanced somewhat from coastal epidemics and land claims, native residents of the Southern interior were still numerous and strong enough to be wooed as potential allies in imperial conflicts and courted as likely markets for European goods. They also proved able producers of an endless supply of furs and pelts drawn from the abundance of game — especially deer — in Southern forests.

Having set aside the Spanish dream of vast mineral wealth, the French and English now concentrated on the ever-expanding deerskin trade. Their colonial settlements had become less reliant upon Native American help for immediate survival and more closely tied to the Old World through regular shipping. The market for Indian labor was drying up, as a vast transatlantic network poured enslaved Africans and European indentured servants into the Southern colonies at great profit to the suppliers. The colonists had learned Indian techniques for raising and smoking tobacco, so they could meet the growing European clamor for this American product. But Europe was also developing a taste for gloves, vests, aprons, and other items made from soft and durable deerskin, and only Southern Indians could meet the rising demand.

This new commerce offered clear advantages to the suppliers. As it rose in importance, it blunted colonial zeal for enslaving Indians and grabbing their land, since white traders depended on peaceful conditions to protect their livelihood. The deerskin trade also tapped a seemingly limitless resource, utilizing traditional Indian hunting and curing skills developed over centuries. At the same time, it brought useful trade goods into Indian communities, modifying and improving many daily tasks without revolutionizing them. Iron cooking kettles lasted longer than clay pots; metal hoes cleared gardens more easily than wooden digging sticks; glass beads for jewelry and embroidering were less expensive than traditional peak made from shells.

But the disadvantages of trade with the Europeans gradually emerged. At first, Indian burdeners were paid to carry heavy packs of skins hundreds of miles to navigable rivers or port towns. As horses became more common in the region, trains of pack animals took over the transportation, and colonial merchants absorbed the profits. Improved transportation also increased the number of European traders vying for commerce in the interior. Besides foreign customs and strange diseases, they brought with them trade goods that created long-term dependency. Guns for hunting and warfare, for instance, increased local military power and aided in procuring skins, but users became reliant upon Europeans to provide gunpowder and make repairs, while losing skill with their traditional weapons. Indians in Virginia “use nothing but firearms, which they purchased from the English for skins,” observed William Byrd in 1728. “Bows and arrows are grown into disuse, except only amongst their boys.”

Another trading staple, rum, also fostered crippling dependency. Long before Westerners began selling opium to the Chinese and cigarettes to the Third World, colonists realized that addictive substances could secure commerce. Slave-based sugar plantations in the Caribbean gave white entrepreneurs a ready source of molasses from which to distill cheap rum, and soon they were transporting casks of the demon drink into the backcountry.

Indians, unfamiliar with sugar-based alcohol, became eager buyers of the addictive brew. Southern Indian leaders looked on in dismay as traders used liquor to leverage their people into debt and keep them there. Some fought back. Indeed, Creek headmen organized what may have been the first prohibition movement in North America, sending scouts out to smash rum casks on the trail before pack trains could enter their territory and intoxicate their hunters.

Even the sheer success of the deerskin trade began to prove burdensome. At the beginning of the 18th century, England already imported an average of nearly 54,000 deerskins from the Carolina colonies each year. By the 1730s Charleston was shipping 80,000 deerskins annually, and by 1748 that figure had doubled. “There was a falling off in the early 1750s but another peak was reached in 1763,” according to historian Verner Crane. “These exports, of course, represented a tremendous slaughter of deer, comparable to the great wastage, by a later generation, of the buffalo of the Great Plains.”

Stung Serpent

When the French began colonizing Louisiana in the 18th century, they encountered the highly stratified and centralized society of the Natchez Indians. The noble class was led by the family of the Great Sun, hereditary rulers thought to have divine ancestry. The Natchez still used the temple mounds of their Mississippian ancestors, and they continued a practice of sacrificial killing dating from Woodland times. When a member of the Great Sun lineage died, relatives and servants volunteered to be put to death to accompany the deceased.

A Frenchman named Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz lived among the Natchez for eight years before the war of 1729 destroyed their community and culture. He wrote in detail about everything, from language and religion to food and daily appearance. Le Page described the elaborate tattoos of the Natchez and commented:

"The youths here are as much taken up about dress, and as fond of vying with each other in finery as in other countries; they paint themselves with vermilion very often; they clip off the hair from the crown of the head, and there place a piece of swan’s skin with the down on; to a few hairs that they leave on that part of their hair they fasten the finest white feathers that they can meet with; a part of their hair they weave into a cue, which hangs over their left ear.”

After his arrival in 1720, Le Page became well acquainted with Stung Serpent, sometimes called Tattooed Serpent—the elder leader of the Natchez and younger brother of the aged Great Sun. In his memoirs, Le Page relates how he “one day stopped the Stung Serpent” and sounded him out about his reactions to the French.

"We know not what to think of the French," the Indian replied. “Why, continued he, with an air of displeasure, did the French come into our country? We did not go to seek them: they asked for land of us, because their country was too little for all the men that were in it. We told them they might take land where they pleased, there was enough for them and for us; that it was good the same sun should enlighten us both, and that we would give them of our provisions, assist them to build, and to labour in their fields. We have done so; is this not true? What occasion then had we for Frenchmen? Before they came, did we not live better than we do, seeing we deprive ourselves of a part of our corn, our game, and fish, to give a part to them? In what respect, then, had we occasion for them? Was it for their guns? The bows and arrows which we used, were sufficient to make us live well. Was it for their white, blue, and red blankets? We can do well enough with buffalo skins, which are warmer; our women wrought feather-blankets for the winter, and mulberry-mantles for the summer; which were not so beautiful; but our women were more laborious and less vain than they are now. In fine, before the arrival of the French, we lived like men who can be satisfied with what they have; whereas at this day we are like slaves, who are not suffered to do as they please.”

Not long after this encounter, Stung Serpent fell ill. Le Page recalls how his death was announced in the spring of 1725 "by the firing of two muskets, which were answered by the other villages, and immediately great cries and lamentations were heard on all sides.

"Before we went to our lodgings we entered the hut of the deceased, and found him on his bed of state, dressed in his finest cloaths, his face painted with vermilion, shod as if for a journey, with his feather-crown on his head. To his bed were fastened his arms, which consisted of a double-barreled gun, a pistol, a bow, a quiver full of arrows, and a tomahawk. Round his bed were placed all the calumets of peace he had received during his life, and on a pole, planted in the ground near it, hung a chain of forty-six rings of cane painted red, to express the number of enemies he had slain. All his domesticks were around him, and they presented victuals to him at the usual hours, as if he were alive. The company in his hut was composed of his favourite wife, of a second wife, which he kept in another village, and visited when his favourite was with child; of his chancellor, his physician, his chief domestic, his pipebearer, and some old women, who were all to be strangled at his interment. To these victims a noble woman voluntarily joined herself, resolving, from her friendship to the Stung Serpent, to go and live with him in the country of spirits.”

As deer became more scarce, Indian hunters had to stay in the field longer, kill smaller animals, and carry their trophies over greater distances. In communities already diminished by disease, family members had less time for gathering strawberries, observing the Green Com ceremony, or taking part in other activities that made village life meaningful and self-sufficient. By the 1760s, deerskins had even become an accepted medium of exchange between Native Americans. “If one man kills another’s horse, breaks his gun, or destroys anything belonging to him, by accident or intentionally when in liquor; the value in deerskins is ascertained before the Beloved Man,” noted John Stuart, the English Superintendent of Indian Affairs. “If the aggressor has not the quantity of leather ready he either collects it amongst his relations or goes into the woods to hunt for it.”

For years, Indians contained the harsh effects of the expanding deerskin trade through diplomacy. Traders from Virginia, the Carolinas, and the aggressive new colony of Georgia could be played off against one another. English agents could also be pitted against traders from Spanish Pensacola or French New Orleans to see who could offer the steadiest flow of high quality goods at the lowest prices. Since each European power wished to expand its markets, extend its territorial control, and secure its settlers from attack, skilled Indian negotiators were able to drive hard bargains. Many made annual trips to the coast to exchange gifts, benefiting their people while reinforcing traditional ideas of collective and reciprocal gift exchange — an economic custom increasingly threatened by foreign notions of individual, capitalist acquisition.

Some leaders, like Old Brims of the Creeks, elevated diplomacy to a high art, pitting rival European powers against one another much the way neutral Third World countries bargained between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War. But as recent history demonstrates, when conflicts between superpowers recede, the bargaining strength of small nations is reduced. And in 1763, the balance of colonial power shifted dramatically in the South.

For generations, the French had built forts in the interior and recruited Indian allies in hopes of driving English settlers out of North America. But the greater numbers and superior trade goods of the English proved more powerful. In 1763, following the English victory in the Seven Years War, the French surrendered their claim to Canada and Louisiana. That same year, the Spanish ceded Florida to the British. After two centuries of colonial struggle, England suddenly claimed unrivaled control of eastern North America.

The implications were not lost on Indian leaders. Within months an Ottawa war chief named Pontiac had forged an alliance in the Northwest, hoping that warriors from the Huron, Chippewa, Iroquois, Shawnee, and other tribes could push the English back from the Ohio and Mississippi Valley before the French had fully vacated the region. Had Pontiac been able to sustain the initial successes of his dramatic uprising, he might have been joined by Southern Indians who also feared the withdrawal of England’s European rivals. The “Indian War of Independence” failed, but it managed to frighten the young British king. In 1763, George III proclaimed that no colonist was to settle beyond the Appalachian divide, for fear of provoking Native Americans into a war that would absorb the empire’s money, endanger its subjects, and damage its trade.

Debts and Deals

The crown, however, could not enforce its royal proclamation. With the French threat removed, English settlers in coastal colonies were eager to move west beyond the mountains — and wealthy speculators were anxious to obtain title to frontier lands that could be sold to small farmers at a profit. Using debts created through the deerskin trade, plus the threat of force, syndicates of white investors with government connections negotiated a series of valuable land cessions.

Oconostota and other Cherokee leaders conceded lands in treaties at Hard Labor (1768) and Lochaber (1770) in hopes of preventing further encroachments. The largest transfer occurred in 1773, when the Creeks ceded more than two million acres to Georgia to satisfy the demands of English traders for payment on previous debts. In 1774, Virginia speculators and frontiersmen used military power against the Shawnee leader Cornstalk and his allies at Point Pleasant to force the concession of lands in eastern Kentucky.

Many private investors simply ignored official warnings against the purchase of land beyond the Appalachian divide. At Sycamore Shoals on Tennessee’s Watauga River in March 1775, Judge Richard Henderson and Daniel Boone of the Transylvania Company distributed six wagon loads of goods to the Cherokees. In return, Oconostota and several other elderly chiefs who had agreed to earlier land cessions signed over a huge tract of 17 million acres between the Kentucky and Cumberland Rivers, cutting off the Cherokees from their northern hunting grounds and the Ohio River.

As Henderson completed his illegal purchase, a group of younger warriors — defying the usual Indian protocol of bargaining by consensus and deferring to elders — walked out of the conference in protest. “You have bought a fair land, but there is a cloud hanging over it,” their leader, Dragging Canoe, told the buyers. “You will find its settlement dark and bloody.”

A month later the Battle of Lexington marked the opening of the Revolutionary War. Most Native Americans sided with the English, who desired trade, against the rebellious Americans, who wanted land. Dragging Canoe led a siege on the new Watauga settlement in July 1776, prompting a scorched-earth counter offensive by the Americans in the fall. Their villages in ruin, most Cherokees felt obliged to accept neutrality, but Dragging Canoe led a band of holdouts westward into the mountains around present-day Chattanooga. Joined by guerrilla fighters from other tribes, they became known as the “Chicamaugas” and carried on their resistance with supplies from British agents in Pensacola.

When the English finally lost the war, their Indian allies did not fare well at the peace table. The defeated British made no mention of Native Americans in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, ceding all the land north of Florida and east of the Mississippi to the new American confederation. Abandoned by the English, the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Chickasaws negotiated treaties with confederation officials at Hopewell, South Carolina in 1785, only to discover that the weak central government could not protect them from aggressive states.

While Dragging Canoe and his Chicamaugas continued their armed resistance, others attempted to maneuver diplomatically. Alexander McGillivray, a mixed-blood Creek chief, tried to pull together a confederation of Southern Indians, with encouragement from Spanish officials at New Orleans and Chickasaw Bluffs, the site of present-day Memphis. But in 1790, George Washington’s new government invited McGillivray to New York, showered him with money and honors, and successfully concluded a peace treaty with the Creeks.

Two years later Dragging Canoe died at the age of 60; his resistance movement outlived him by only a few years. But he and his generation had experienced more than one revolution. In the two decades since American independence from England, the native hunting grounds west of Cumberland Gap had been transformed by a flood of new immigrants. By 1790 there were suddenly more than 60,000 whites and 13,000 blacks living in what would soon become Tennessee and Kentucky.

The abrupt transformation in the west reflected far wider shifts in Southern population during the 18th century. At the start of the 1700s, Native Americans had been in the majority, numbering well over 130,000 people. But Indians were dying at a much faster rate than blacks and whites were arriving, reducing the population of the region to an all-time low. By 1776, the number of native Southerners had plummeted to fewer than 60,000.

After the Revolutionary War, the Indian population began to increase slightly. But the non-Indian population was growing many times faster — and numbers translated into economic and cultural power. Throughout much of the region, English was becoming the dominant language, Protestant Christianity was emerging as the dominant religion, and, on paper at least, the newly adopted Constitution was the law of the land. “Indian Nations before the Whites,” observed a Cherokee at Sycamore Shoals, “are like balls of snow before the sun.”

By 1790 there were more than one million Europeans and half a million Africans living in the region — and the pressure for additional access to Indian land was continuing to build. For Native Americans, the withering Southern sun would burn ever more fiercely in the coming century.

Tags

Peter H. Wood

Peter H. Wood is an emeritus professor of history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He is co-author of the U.S. history survey text, "Created Equal," now in its fifth edition.