This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

In 1911 Marie Kriss, a seven-year old Polish girl, shucked oysters on the Mississippi coast for 25 cents a day. Sixty years later she still recalled with fondness the savory aromas of the breads, kielbasa, and potato dumplings that her mother prepared in their migrant camp. Cooked on outdoor ovens that her father handcrafted from clay and straw, these traditional Polish foods had made the foreign saltmarsh smell like home. But their memory had not left Kriss with any delusions about her childhood visits to the South. “It was,” she remembered, “like slavery days.”

Mexican campesinas are not the first migrant workers to labor in the Southern seafood industry. From 1890 to the 1920s, several thousand European immigrants traveled to the region from Baltimore each winter to work in oyster and shrimp canneries. Like the Kriss family, most had emigrated from Poland. But Bohemian, Italian, Serbian, Dalmatian, German, and Irish immigrants also made the journey, working in dozens of remote fishing villages from Swan Quarter, North Carolina to Houma, Louisiana.

Before 1890, the oyster industry in the South was relatively small. But as Chesapeake Bay oysters were depleted in the late 19th century, the great canning companies based in Baltimore began to open branch plants along the Gulf and South Atlantic coasts. Recruited largely from the impoverished Baltimore canning districts of Fells Point and Canton, European immigrants worked in the South for three to six months every winter. They returned north in the spring to pick crops in Delaware and Maryland, finishing in time for the peak season at the oyster, vegetable, and fruit canneries clustered on Boston Street in Baltimore.

The arrival of the “Baltimore workers” along the Southern coast grew into a seasonal rite of passage as regular as the late summer mullet runs or the autumnal shift in prevailing winds. In the early years, though, local residents found the migrants strange and exotic. The Biloxi Herald noted on January 11, 1890 that Gulf Coast residents stared with open mouths at their first sight of the migrant workers. The newcomers wore peasant clothes, spoke little or no English, and had Old World bearings which—in the case of the Polish workers —were etched by years of famine and Russian despotism.

For the new arrivals, the South must have been lonely and no less strange. The Polish workers had left Baltimore neighborhoods where they were often in the majority. There they could read Polish newspapers, patronize Polish stores, and confess to Polish-speaking priests, easing their sense of dislocation from their homeland and its customs. But in Mississippi and the Carolinas they found no such community. “They were,” in the words of one Mississippi, “only Bohicks” in a Jim Crow world not disposed to subtle distinctions. Many inevitably longed for St. Stanislaus Kostka, the Catholic church in Fells Point around which much of Polish life revolved, as well as for the social clubs and self-help associations spawned by the Polish National Alliance and Polish Home.

Nevertheless, the newcomers struggled to maintain a sense of community in the South. On Sundays a rosary and the Pasterka substituted for mass at “St. Stan’s.” Polish music, festivals, and sacraments were all transplanted to the company settlements, where local citizens occasionally joined the celebrations. “On Saturday nights,” recalled an elderly Biloxi resident who visited with the Poles in his youth, “they played accordion music and had dances, right in the camps.” Another Biloxian remembered attending a Polish wedding during the oyster season, as well as a traditional Polish wake —an all-night celebration of the dead’s passage into Heaven—for an oyster shucker and her baby who died in childbirth.

Strikes and Allies

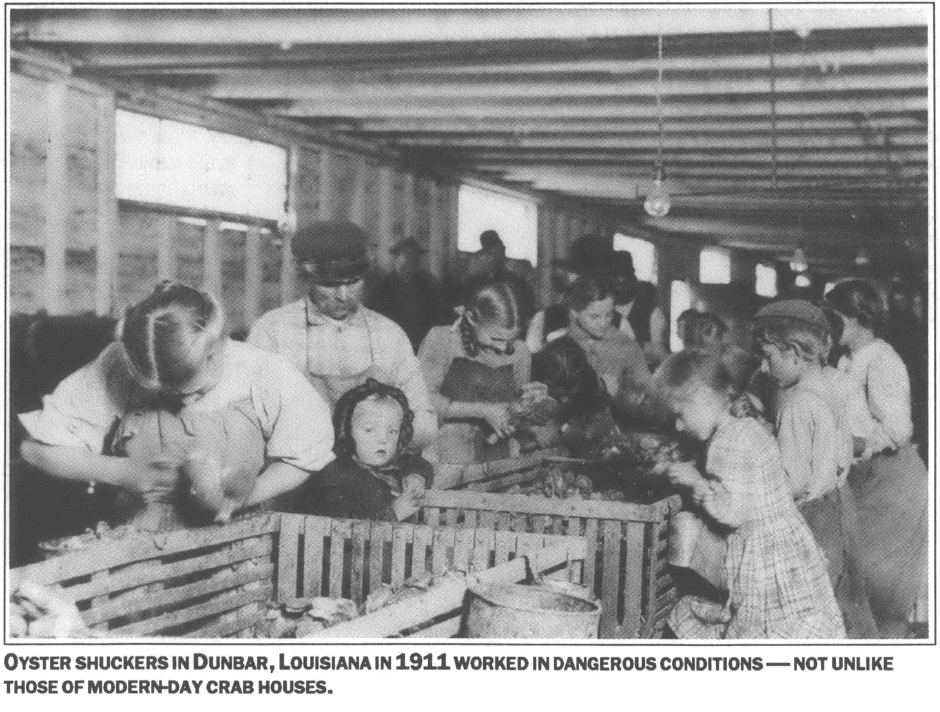

Workers needed these communal bonds to face the rigors of migrant labor in the canneries. Six days a week, in damp sheds, the European immigrants and their children pried apart steamed oysters for twelve-and thirteen-hour shifts. Often they started at three o’clock in the morning. Observing their "hard work—deadening in its monotony, exhausting physically, irregular,” documentary photographer Lewis Hine was “reminded forcibly of sweatshop scenes in large cities.” Children like Marie Kriss might shuck only 25-cents worth a day, but even adults needed stamina and skill to take home five or six dollars a week.

Working conditions were also dangerous. Paid “by the pot,” oyster shuckers worked hard and fast. They frequently cut themselves with the wet, razor-like shells and powerful knives. In 1919, investigators from the U.S. Children’s Bureau discovered that three-fourths of cannery families reported a recent injury. They also documented chronic “weariness and back ache and aching feet ... from the constant standing and bending, and illness from getting wet and cold.”

Shrimp peeling caused the worst pains. Within a few hours the crustacean’ s natural acidity—potent enough to corrode canning tins and rot work gloves— scorched fingers till they bled. The immigrants regularly soaked their hands in alum to ease the pain, and in peroxide to preempt infections. The Children’s Bureau investigators found that few shrimp peelers could work more than two days without taking a day off to allow their hands to heal.

Child labor—usually legal—was widespread and often critical for family survival. In 1911 and 1916, Lewis Hine photographed hundreds of immigrant children under the age of 12 working in shrimp and oyster canneries in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. While fathers and older boys worked on the dredge boats, mothers brought younger children to the cannery, carrying infants in cradles fashioned from crude boxes. The smaller children cared for the babies and shucked oysters when they nursed and napped. The older girls often returned to the camp once or twice a day to prepare coffee and bread to carry back to their families. “Everybody works here,” an 11 -year-old shucker named George Boshorvisky told a Biloxi visitor in 1913. “I know I must help because we’re poor.”

Company housing was no better than the working conditions. In Biloxi, Marie Kriss and her family slept 10 people in two unheated rooms. In Port Royal, South Carolina, 50 oyster shuckers stayed in a row of shacks, eight or more to a room. Open sewage, vermin, and bad drinking water were prevalent. In Swan Quarter shuckers actually lived on the second floor of the cannery, which reeked of foul oysters.

Abusive padrones, or crew bosses, kept workers in virtual peonage, sometimes forcing them to buy all their food from company stores. The complete control over workers was the greatest advantage to hiring migrants over local residents. “We blow the whistle and they have to come,” a cannery owner explained, “else we’ll run ’em out of the camps and refuse to pay their fare back.”

Migrant workers periodically fought back. Between 1908 and 1915, waves of wildcat strikes swept many Southern canneries. In the best documented protests, oyster workers struck for higher wages and more regular work at camps in Biloxi, Mississippi, Morgan City and Houma, Louisiana, and Apalachicola, Florida. In 1913, for example, Polish oyster shuckers in Morgan City twice walked out of the cannery of Dunbar, Lopez, and Dukate, and workers on the oyster dredgers refused to return their boats from the reefs until the company raised their wages.

In their struggles to improve working and living conditions, migrant workers often found local allies, especially among Southern women. During the First World War, for instance, Mrs. J.W. Dampfand other Civic League activists in Pass Christian, Mississippi campaigned successfully to have the local cannery improve migrant housing and provide a playroom for children at work. In 1919 they also charged the town clerk with sexually harassing six cannery workers. Similarly, a cannery foreman in the midst of a Morgan City strike was outraged when “people from the village” had workers “come to town and gave them bread and other food.”

Such gestures of solidarity helped break the isolation that enabled canneries to exploit migrant workers. As communities extended their support to migrants in the late 1910s and early 1920s, the families of Marie Kriss and other Eastern European immigrants began to settle permanently along the Southern coast. Many of them still live in the fishing communities where their ancestors once worked—and where migrant women from Mexico have inherited their struggle for better working conditions.

Tags

David Cecelski

David Cecelski is a historian at the Southern Oral History Program, UNC-Chapel Hill. He is author of Along Freedom Road, which recently won a 1996 Outstanding Book Award from the Gustavis Myers Center for the Study of Human Rights in North America. (1996)