In the Midst of Great Death: 1592-1692

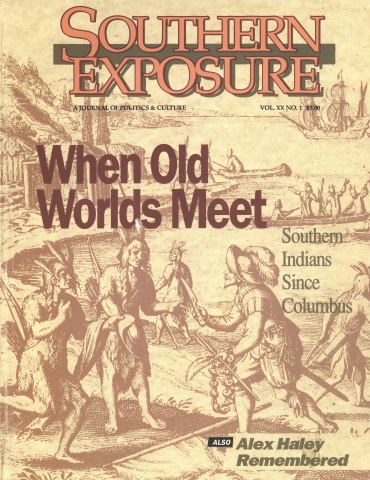

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

“We find that from four years ago down to the present, there have died on account of the great plagues and contagious diseases that the Indians have suffered, half of them,” a Florida missionary reported to the king of Spain in 1617. According to church doctrine, each life lost on earth could become a soul gained in the Christian afterlife if the person had been baptized before death, so the priest hastened to note the bright side he saw in the devastation.

“Your Majesty has had a very great part in the growth that was given to heaven,” observed the flattering cleric. “For with the help of the twenty-two Religious which your Majesty sent... to these regions five years ago, a very rich harvest of souls for heaven has been made in the midst of great numbers of deaths.”

By the time the missionary wrote, epidemics had been ravaging the area the Spanish called La Florida for nearly 100 years. During the 17th century, English newcomers began to occupy bits of the Southern coast in numbers greater than the Spanish or French had been able to muster — extending the clash of cultures and the deadly “harvest of souls” to the coasts of Virginia and Maryland.

The result, say some modern scholars, was nothing short of a holocaust. By 1690 — when usable data for Native American populations began to appear in European records — only an estimated 200,000 Indians survived in the South. Since present-day demographers estimate that the Indian population may have been reduced by as much as 80 percent between 1492 and 1692, it appears that at least one million people had inhabited the South at the time of Columbus, before the onslaught of new maladies.

Just as the Black Death had challenged Christian beliefs in medieval Europe, the New World devastation through disease shook Indian beliefs to their foundations. The enduring balance thought to prevail between humans and the rest of the living world of plants and animals seemed inexplicably disturbed. Native American healers, though skilled in matters where spiritual insight and herbal medicines could play a part, had no remedies for the new afflictions. Some survivors along the coast turned away from their own medicine men and listened, in desperation, to the teachings of the European newcomers. They planted crosses in their villages and accepted Catholic missionaries, hoping that the strange faith could protect them from the depredations of Spanish soldiers and the ravages of disease.

Because fewer Europeans died from such diseases as smallpox, measles, and influenza that they had encountered before, Indian interest in their religion increased. And for oral societies with no written languages, the fact that Christianity was recorded in a book added to its mystery and power. Capitalizing on this leverage, the Spanish sent missionaries among the coastal Indians — with limited success. In Guale, along what is now the Georgia coast, Franciscan priests were put to death in an uprising in 1597. A new generation of friars established missions in northwest Florida during the 1630s, but in 1647 the Apalachee Indians revolted, killing several priests and burning down more than half a dozen churches. Nine years later the Timucuans rebelled in central Florida.

Although willing to hear of another God besides their own, native Southerners were not eager to give up traditional ways. Their balanced economy of fishing, farming, hunting, and gathering required constant mobility, but missionaries insisted upon permanent residence near a makeshift church. The priests also demanded regular backbreaking labor, and they tried to prohibit traditions of polygamy, nakedness, and dancing.

Still, their presence offered hope of economic exchange, military protection, and spiritual favor to some beleaguered groups. By 1655,38 missions, staffed by 70 friars and claiming to serve 26,000 Christianized Indians, existed north and west of St. Augustine. Within another generation, however, these outposts had all but disappeared. Lack of support from Europe contributed, as did continued Indian resistance. In 1680, the Pueblo Indian Revolt against Spanish rule in New Mexico marked the largest successful North American uprising of the colonial era.

Big Salt Bay

The most profound change along the Atlantic coast in the 17th century involved the arrival of settlers from England. While they looked and acted much like earlier Europeans, the English were products of the Protestant Reformation who saw powerful Spain as their religious and economic rival. An initial attempt to establish a colony at Roanoke Island in the 1580s failed, in part because English ships were needed to stave off the Spanish Armada sent to invade England in 1588.

By 1607 England’s increasing commercial and naval strength made possible another, more successful, colonization attempt. The English called the region Virginia after their late virgin Queen, Elizabeth I, and the settlement Jamestown after their current king. But to longtime inhabitants the domain was Tsenacomoco, and the ruler was Powhatan, whose name was linked to the paramount chiefdom he controlled.

Powhatan’s “empire” was a young and still-growing domain that had originated near the fall line of the James and York Rivers, east of modern-day Richmond. Inheriting control of more than half a dozen local groups, Powhatan used aggression to expand his territory and double the number of Algonquian-speaking communities under his confederation. He swiftly emerged as the mamanatowick or “great king” of a paramount chiefdom, extracting tribute from subjects as far north as the Potomac River and across the Chesapeake to the east. A local chief or weroance, owing allegiance to Powhatan, held sway over each separate group, such as the Appamattucks, Rappahannocks, or Pamunkeys.

Those who still resisted the expanding empire in the early 1600s were destroyed or absorbed. Powhatan’s forces annihilated the Chesapeakes, near the mouth of the “big salt bay” from which they took their name. Later he would envelope the Chickahominies, or “crushed corn people,” living in several villages on the northern branch of the James. By the time the English arrived, Powhatan communities numbered an estimated 13,000 people.

At first the English and the Powhatans saw the utility of maintaining friendly relations. Englishmen wanted converts to Protestant Christianity, guides to the countryside, and allies against Spanish forces from the south. The Powhatan communities confidently exchanged turkeys for swords and provided starving Jamestown with countless bushels of corn, hoping the newcomers would prove strong additions to the paramount chiefdom.

But what started in 1607 as a small and useful appendage to Powhatan’s domain soon loomed as a serious threat to the region. Powhatan even allowed his daughter, Pocahontas, to marry an English leader named John Rolfe in 1614 and return to London with him, but the gesture failed to cement a lasting alliance, and Pocahontas died in England after giving birth to a son.

At first, Powhatan thought he could avoid conflict through isolation. “My country is large enough,” he boasted to the English in 1615, that “I will remove my selfe farther from you” if insults persist. But as the English began to grow tobacco for profit and demand more land, relations quickly deteriorated. Former enemies of Powhatan, such as the Monacans to the west, joined with him against the English. Wars erupted in 1622 and 1644, but the Indians could not stem the English tide. Whenever English settlers died, others arrived to take their place.

Powhatan communities were desperate. By midcentury, one observer wrote, the colonists were “takeing away their land and forceing them into such narrow streights and places that they cannot subsist either by planting or hunting.”

In 1676 the English, led by Nathaniel Bacon, attacked several weakened Indian communities to secure more land. The Occaneechee, for example, were forced to move further south, settling at a site on the Eno River that would later become Hillsborough, North Carolina. By 1690 the English completely dominated Virginia east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. More than 40,000 whites and 3,000 blacks lived on land previously controlled by Powhatan, and fewer than 3,000 Indians remained in the vicinity. Most survivors were confined to small reservations and forced to pay an annual tribute to remain on the land they had once hunted. On the Eastern Shore, the Accomacs were confined to one reservation, the Choptanks and Nanticokes to another.

“The Indians of Virginia are almost wasted,” Robert Beverley observed in 1705. But a few native Virginians survived the sickness, warfare, and land loss. Such pressures “did not result in the complete disappearance of all the Powhatan groups by 1700 — or 1800 or 1900,” says Helen Rountree, an Indian expert at Old Dominion University. Like other native Southerners, she adds, they were “people who refused to vanish.”

Paths of Trade

Although native and foreign cultures clashed near Chesapeake Bay in the 1600s as they had at Florida missions in the 1500s, almost the entire South still remained free of colonization in 1650. In the 1660s a few English migrants entered the Albemarle region of North Carolina, and during the 1670s colonists from England and the Caribbean began to occupy the South Carolina coast. In 1682 the French explorer La Salle, using Indian translators and guides, descended the Mississippi to the Gulf, noting that the population was considerably reduced since the time of de Soto. He later returned by sea with a colonizing expedition, hoping to establish a town at the mouth of the river, but his venture foundered on the east Texas coast, and the few survivors were absorbed into Indian groups.

By 1690 — two centuries after the arrival of Columbus — only tidewater Virginia had a sizable colonial settlement, numbering more than 43,000. Elsewhere, from the Outer Banks to east Texas, roughly 10,000 whites and 1,000 blacks clustered in a few tiny coastal enclaves. The rest of the vast region remained the exclusive domain of nearly 200,000 Native Southerners.

As a few colonizers began to explore the Southern interior, they discovered the inhabitants linked by extensive trade networks. The Spanish found Calusa Indians traveling by dugout canoe from Tampa Bay all the way to Cuba to exchange such valuable light-weight items as feathers and bird wings. Communication between the Southern coast and the hinterland flowed along Appalachian rivers like the Potomac, Santee, Savannah, Chattahoochee, and Coosa, and warriors and traders in the Mississippi Valley used the Red, the Ohio, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee as thoroughfares. For centuries Native Americans had also been trading along a grid of overland trails joining one river valley to another. Most followed natural contours, such as the “Great Warrior Path” which ran along the Shenandoah Valley. Many of these trails eventually become white trade routes, such as the Natchez Trace, extending northeast from the lower Mississippi to the future site of Nashville. Local pathways and secondary arteries connected to each major thoroughfare.

Native Americans transported goods of all kinds along these trails. The Tequestas in south Florida trafficked in dried whale meat. Elsewhere, coastal Indians carried dried fish inland, along with shark teeth, pearls, and a variety of shells. Conch shells could be made into horns, cups, and gorgets, while the polished cylindrical beads known as peak came from the central stem of the quahog shell. Roanoke (disks cut from cockles, mussels and other thin shells and pierced with a central hole) was often hung from the ear as decoration or strung together for exchange. In addition, the warmer coastal areas provided the South with yaupon holly leaves, the ingredient for the strong “black drink” consumed regularly at public ceremonies.

In return, inland traders might supply tobacco, flint, salt, soapstone, and the hides of buffalo, which were common in the interior mountains. Like the Spanish explorers before them, the first Englishmen to venture inland experienced the network of trading paths firsthand. Gabriel Arthur, a prisoner among Indians near the French Broad River in North Carolina during the 1670s, accompanied them to Port Royal Sound, Mobile Bay, and the Ohio River Valley.

In the next decade traders from Charleston, South Carolina ventured inland along Indian paths to trade with a Muskogean-speaking group. The Indians were living along Ochese Creek, a branch of the Ocmulgee River, to take advantage of commerce with the Carolina colony. So the English traders called them the Creek people, and established a new commerce.

European goods also flowed between Indian groups along established lines of trade. When John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay in 1608, he found that inhabitants at the head of the bay already possessed numerous European hatchets, knives, and pieces of brass and iron that had been traded southward from the French in Canada. After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Spanish horses began spreading east from New Mexico via familiar trade routes across the Mississippi. The Chickasaw people, living in what is now northern Mississippi, became significant middlemen, and one breed of mounts became known in the South as Chickasaw horses.

Community and Culture

At the end of each trading path lay an Indian town, usually inhabited by several hundred people. A nearby river provided fish, caught with spears, arrows, hooks, or traps. Some Indians even ground up buckeyes and sprinkled the toxic powder in a pool; the organic poison attacked the central nervous system of the fishes so they could be pulled in by hand. The river also created fertile bottomland for cleared fields where hills of corn and squash were farmed communally by the local women. If the soil became exhausted or the supply of firewood ran thin, a community would simply move, limiting the demand on local resources. Many Europeans made their settlements in these “Indian Old Fields,” which had already been cleared and cultivated.

These open fields, created by stripping a ring of sap-carrying bark from trees and letting them die, let sunlight into the adjoining woods and allowed grass and leafy plants to grow along the “edge,” which in turn attracted game. The Indians occasionally burned wooded areas to flush animals into the open, but the practice also cleared undergrowth, revitalized the soil, and encouraged new grass which lured deer to graze in predictable places where they could be hunted more easily with bow and arrow.

Hunting was a necessity, not a sport, and Indians were careful to ask the pardon of animals they killed. The first animal killed during a hunt was treated as a sacrifice, and Indians often threw a portion of their meat into the fire as a further offering when they ate. Everywhere the local woods provided abundant small game. The Cherokees used blowguns made of bamboo to shoot darts at squirrels and rabbits, but bows and arrows were the weapon of choice in hunting wild turkeys, black bears, and white-tailed deer.

The homes to which hunting men and farming women returned varied with the locality. Native Virginians built oblong houses that had sapling frames and barrel-shaped roofs resembling the long houses of their distant relatives, the Iroquois. Farther south among the Upper and Lower Creeks, dwellings were thatched with cane. According to anthropologist Peter Nabokov, vertical walls on their winter houses were “plastered inside and out, with a very small opening which is closed at dark and a fire being made within it remains heated like an oven, so that clothing is not needed at night. Baby boys slept on panther skins and baby girls slept on soft, tanned fawn skins, which the Indians believed would impart the appropriate masculine and feminine traits to their children.”

For the Creeks and other groups with roots in Mississippian culture, the town itself surrounded a four-sided “square ground,” oriented to the four primary directions. Nearby stood a circular council house, built around eight upright poles. (Four and eight were considered special numbers.) The sacred fire was kept at the square ground, where the annual Green Corn ceremony took place. Ancient mounds sometimes flanked the square.

Most towns also had a very large ball court — a wide ceremonial expanse, often 250 yards in length, surrounded by a low embankment for spectators. Residents kept the court swept and strewn with fresh sand for playing the ancient game of chunkey. Players rolled a stone disc and then tossed poles after it, betting on who could hit closest to where the stone would stop. Dominating the open space was a large pole of stripped pine, 30 or 40 feet high, used as the goal for several ritual ball games, one of which was a Southern ancestor of lacrosse.

Though much smaller and less numerous than they had been in the heyday of Mississippian culture, most Southern towns of the 17th century still functioned in traditional ways. But word of further change was in the wind. In 1671 two Englishmen named Thomas Batts and Robert Fallam headed west from the Chesapeake, crossing the Appalachian divide in southwest Virginia to where the Tug Fork River divides West Virginia from Kentucky. Like all Europeans of the time, they remained thoroughly ignorant of the true geography of America. Hoping to find access to the Pacific, they scanned the horizon for water and watched the west flowing streams for signs of tidal ebb and flow. Instead, Batts and Fallam saw the eastern edge of the vast Mississippi Valley, which French Canadians were beginning to explore from the north. Along the way they met an Indian who had come from farther west on his own journey of exploration, trying to confirm rumors about the arrival of strangers. Over the next 100 years, such rumors would prove all too true.

Tags

Peter H. Wood

Peter H. Wood is an emeritus professor of history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He is co-author of the U.S. history survey text, "Created Equal," now in its fifth edition.