This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

Step into the Southern workforce of the 1990s, and enter a terrifying world where a small but vocal minority dominates the entire economy.

The minorities represent barely a third of the population, yet they have managed to use their skin color and gender to get the best jobs — often squeezing out majority applicants who are better educated and more qualified. Thanks to the preferential treatment they receive in hiring and promotion, the minorities hold half of the white-collar professional jobs, two-thirds of the top management positions, and three-quarters of all skilled trades jobs.

They are the boss. They tell the majority what to do. When the majority of workers ask for tougher laws to ensure they are treated fairly, the minorities scream about “racial quotas” and “reverse discrimination.”

Can it be? Have the nightmares of white supremacists like David Duke come true? Do minorities really rule the workforce?

They do — but the minorities who hold a disproportionate share of the good jobs are white men, not blacks and women.

White men make up approximately 38 percent of the population of the South, yet they hold 67 percent of the top white-collar jobs in private industry and 71 percent of the best blue-collar jobs. By contrast, they fill only 11 percent of all pink-collar clerical positions and just 22 percent of the lowest-paying service jobs.

The continuing dominance of white men in private industry has often gone unmentioned in the current debate over federal affirmative action laws. Indeed, “affirmative action” has become virtually synonymous with “special treatment for minorities.” But in reality, federal employment mandates are designed to protect the majority of workers — the 6.2 million women, blacks, and other people of color who now comprise nearly 60 percent of the private labor force in the South.

Have affirmative action programs really helped most workers? To answer that question, the Institute for Southern Studies has conducted a state-by-state review of job data from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The study examined the race, gender, and jobs of 42 million workers employed by over 38,000 companies that do business with the federal government — nearly half of all private payroll employees in the nation.

The findings indicate remarkable progress throughout the South. Since 1970, women and non-whites in the region have made substantial gains in every sector of the economy. Some of the biggest strides were made by white women entering professional jobs and by black men breaking into the skilled trades.

But the study also indicates that much more remains to be done to ensure fair employment in the region. After two decades of affirmative action, white men still dominate the private labor force — and most blacks and women are still segregated in jobs that offer the lowest pay and the least responsibility.

“White males are not turning over to minorities and females any of the leadership roles in corporate America,” says Peter Roulhac, a former affirmative action manager for a Miami bank. “I can understand the perception of some white males that they’re being discriminated against, but if you did a fair statistical analysis, white males have not been negatively impacted at all.”

Goodbye Good Jobs

An analysis of federal statistics suggests that the greatest impact on all workers, white males or otherwise, has come from the shifting economy. Since 1980, manufacturing jobs have ground to a halt, especially in traditional Southern industries like textiles and tobacco. Lower-paying service and trade jobs now employ nearly half of all Southerners — up from one third in 1969 (see “The South at Work,” SE Vol. XVIII, No. 3). The result: Good jobs are harder to come by, even when the economy is good.

At the same time, women across the country have been entering the workforce in greater numbers than ever before. Seventy percent of women ages 25 to 54 now work, up from 50 percent at the beginning of the 1970s.

The growing number of women in the workforce has meant increasing competition for a dwindling number of good jobs. When Ashland Oil — the eighth-largest public corporation in the South — expanded its refinery in Catlettsburg, Kentucky in February, 2,200 job seekers waited hours in freezing temperatures to apply for 25 openings. The company set up portable toilets and water coolers for the applicants, many of whom spent more than a day standing in line for a crack at an $11-an-hour refinery job.

As white men have felt the job squeeze, some have blamed affirmative action. “I spent 20 years in the trade, and a girl who spent one year in the trade became my foreman,” says one male painter who filed a complaint with the EEOC. “That really hurt me.”

“I have no bad intentions against any one person,” says Bill Anderson, a white Miami firefighter who claims he was passed over for promotion in favor of less-qualified blacks and Hispanics. “It’s just the system.”

The “system” of affirmative action dates back to World War II, when President Franklin Roosevelt ordered defense contractors to halt discriminatory hiring practices. In 1961, President John Kennedy introduced the phrase “affirmative action” in Executive Order 109255, imposing the first federal sanctions on government Black men have nearly doubled their share of skilled contractors who violate trade jobs since 1970, but white men still hold nearly minority hiring rules.

Four years later, President Lyndon Johnson ordered federal contractors to develop written plans detailing how they would overcome ingrained recruitment practices and create equal job opportunities for blacks and women. The overall goal was to diversify private industry by taking positive steps to pry open the “good ole boy” system — the relatively small, informal networks that most firms rely on to find new employees.

In the past decade, however, federal enforcement of anti-discrimination laws has slackened, as both the Reagan and Bush administrations have fought to weaken civil rights initiatives. In addition, federal courts have handed down several rulings that make it harder for blacks and women to prove job discrimination — and easier for white men to claim reverse discrimination.

“With the conservative mood of the country, affirmative action doesn’t appear to be getting the attention it had in the past,” Doug Cunningham, senior vice president of NationsBank, told the Tampa Tribune. “It’s very lax right now.”

Working Women

Despite the lack of enforcement in recent years, EEOC data confirm that affirmative action has helped Southern blacks and women make significant inroads in private industry since 1970. Consider the overall gains:

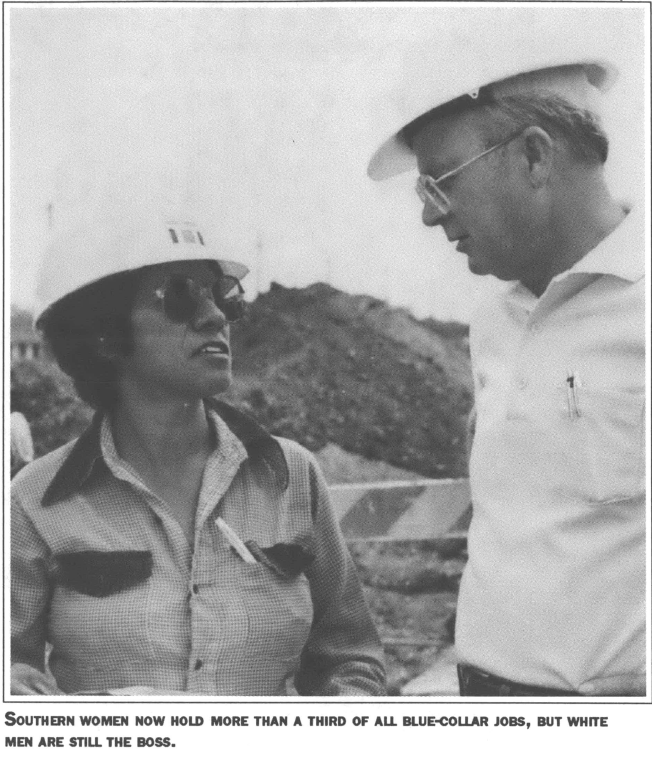

Women made up 46 percent of the private industry payroll in the region in 1990, up from 36 percent in 1970. Female workers increased their share in every job category, filling nearly half of white-collar professional spots and more than a third of all blue-collar jobs.

Black workers increased their share of the Southern labor force from 15 percent in 1970 to nearly 20 percent in 1990. The number of African-Americans in white-collar jobs more than doubled to 10 percent, and the black share of blue-collar jobs bucked a regional downturn, increasing to 27 percent.

“It’s very clear that affirmative action programs have made lots of better jobs available to people who have been kept out of them in the past,” says Steve Ralston, deputy director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “The progress for both women and black workers has been dramatic.”

Among workers protected by affirmative action laws, Southern women appear to have fared the best. Indeed, women in the region now hold an almost equal share of all jobs in private industry. In 1970, women made up barely a third of the workforce in most Southern states; today their slice of the employment pie ranges from a low of 40 percent in Louisiana to a high of nearly 50 percent in Florida.

Women in the South have always worked outside the home in higher proportions than their non-Southern counterparts, and they have always been more likely to hold manufacturing jobs. But EEOC figures show that the rest of the nation has undergone something of a “Southernization” of the workforce in the past two decades. For the first time, women now hold a slightly greater share of jobs outside the region than in the South.

Nevertheless, Southern women still maintain a bigger share of blue-and pink-collar jobs than women outside the region. In 1990, women made up over 35 percent of the blue-collar labor force in every Southern state except Louisiana, Texas, West Virginia, and Kentucky — energy-dependent states where men still dominate the coal mines and oil fields.

The employment gains have occurred across the board:

White Collar. Women make up 44 percent of all managerial, professional, technical, and sales jobs — up from 25 percent in 1970. One of every four top managers is now a woman, compared to fewer than one in 10 two decades ago.

“Affirmative action has helped women with professional training and an educational background break into a wider range of professions beyond nursing and teaching,” says Barbara Smith, professor of sociology at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. “Today we have more women lawyers, more doctors, more engineers. Affirmative action helped open some of those doors.”

Blue Collar and Service. Southern women now hold more than one of every three jobs in this category, but most remain relegated to low-paying positions in service and unskilled labor. Barely one in 10 skilled crafts jobs is held by women.

“Women who try to break into the building trades face an all-male club,” says Chris Weiss, a West Virginia organizer who founded Women and Employment, Inc. in 1980 to train women for non-traditional jobs. “Women who went to work on building sites would be threatened and harassed. The family is real important here, so when you had these uppity women come along who didn’t have a father in the trades, it didn’t sit well with the men.”

Pink Collar. Office and clerical jobs — long treated as “women’s work” — grew even more female-exclusive in the past two decades. Women now hold a whopping 85 percent of manual office jobs, up from 77 percent in 1970.

Black-Collar Jobs

Although affirmative action was initially created during the early days of the civil rights movement as a remedy for racial discrimination, it now seems that black workers have not fared as well as women in the past two decades.

“Affirmative action for women is as necessary as for Afro-Americans or any other group,” says Mike Sheely, a North Carolina attorney who specializes in employment discrimination cases. “But after 25 years, it appears that white women are in better jobs at a greater rate than black men. I see a whole lot more white women lawyers than black lawyers in the major downtown firms.”

Data from the EEOC bear out such observations. Since 1970, the share of black men in white-collar jobs has edged up to just over four percent — nearly double the rate 20 years ago. But the overall share of black men in the Southern workforce has actually declined by 10 percent since 1970. Most of the drop came in blue-collar jobs, as black women in the region have replaced black men as unskilled laborers and service workers.

Indeed, black women now hold one of every 10 Southern jobs, compared to one of 11 for black men. African-American women outnumber men among the ranks of white-collar professionals and technicians, as well as in service and sales jobs.

Affirmative action helped open the factory doors for black women. “Beginning in 1969, there was an industry-wide change in the textile industry,” says Richard Seymour of the Lawyer’s Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law. “For the first time, you saw large numbers of black women able to get jobs in textile mills. For many, it was their first factory job. There’s no question in my mind that government enforcement of affirmative action made an enormous difference in the lives of black women.”

But for black men and women alike, most employment gains over the past 20 years have taken place at the bottom of the job ladder. “Companies are hiring blacks, but they’re sticking them in low-paying jobs,” says attorney Mike Sheely. “Once a company reaches what it deems to be an appropriate hiring level, it just stops hiring blacks.”

Across the region, the “good ole boy” network remains strong — and black workers remain stuck in the most dangerous and dirty jobs:

White Collar. Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina — the Southern states where blacks make up the largest share of the population — discriminate the most against blacks in white collar work. Blacks have the fairest share of white-collar jobs in Virginia and the five Southern states with the smallest black populations — West Virginia, Texas, Florida, and Kentucky.

Blue Collar and Service. Manual work remains disproportionately black work in every Southern state. Once again, Mississippi has the worst record, giving black workers 47 percent of all blue-collar jobs, but a meager 17 percent of white-collar jobs.

Pink Collar. Like women, black workers have been shunted into office and clerical work in greater numbers over the past two decades. Over 17 percent of all pink-collar jobs now go to blacks — most of them women — compared to less than six percent in 1970.

Segregation at Work

For black and female workers in the South, such numbers tell the story. Affirmative action has helped open doors to employment with many private firms — but once inside, women and people of color still face enormous barriers. As a result, the workforce remains starkly segregated along lines of race and gender.

“Black workers broke through the initial barriers early on in the 1970s,” says Steve Ralston of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “Since then, our litigation has focused on what happens after you get the job. Blacks can get hired, but they often have trouble getting promoted. They tend to be in the dead-end jobs, while whites move up rapidly.”

As blacks and women have entered private industry in record numbers, racial and sexual discrimination on the job have become major issues. “Many of my cases now involve promotions and firings,” says Mike Sheely, the North Carolina attorney. “Blacks are slower to be promoted and quicker to get fired than whites.”

Floyd Pough discovered “job segregation” when he graduated from college in 1976 and became the first black man hired as a project accountant at a large company in Mobile, Alabama. Soon after he took the job, he noticed that the boss only invited white employees to his home for cocktails or to go fishing with him. When it came time for promotion, Pough was told he was doing good work — but his probationary period was extended.

“Telling me I’m doing a good job but not ready to move up to the next level is double talk,” says Pough, now the director of the Mobile Community Action Agency. “A lot of times promotions come from within — but they are based on the color of your skin and what school you attended.” Frustrated by his inability to advance in the firm, Pough quit after a year.

Such experiences are all too common. The Reverend Nimrod Reynolds, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference chapter in Anniston, Alabama, Black workers have not fared as well as women in the past two decades. recently accompanied a black man who had filed an EEOC complaint to his discrimination hearing. “This man says he was fired because he’s black,” says Reynolds. “He says that of every 10 people fired at his company, eight are black.”

As federal enforcement of affirmative action guidelines has slackened, cases of job discrimination have increased. Last year alone, 63,898 workers filed complaints with the EEOC — up from 56,228 a decade ago.

Among those filing a complaint was Regene Radford, a fashion designer who took a job at a weight-loss clinic to make ends meet while she built up her own business. Lloyd Liming, the owner of the clinic in Waynesville, Virginia, hired her one Friday — but over the weekend, he apparently had second thoughts.

On Monday, clinic manager Kim Fisher approached Radford and said she had just received a call from Liming. “You won’t believe what that man just said,” Fisher told her. “He said he’s going to have to get rid of you because you’re black, and you’ll attract a lot of black clients and his business will go down.”

Liming didn’t fire her immediately, Radford says — but over the next two months, he called the clinic repeatedly to check on how many black clients were coming in. “It was like I was on pins and needles,” Radford recalls. “I never knew when I would go in and find somebody else sitting in my seat.”

Liming finally sent an assistant to fire Radford — and Radford went to the EEOC. The agency has filed a lawsuit against Liming in U.S. District Court in Charlottesville.

Radford says the experience taught her that racism is still rampant in the workplace. “It’s prevalent,” she says. “I’m not going to say it’s targeted to the South. It’s everywhere. My case just happened to have been located in the South. It’s sickening. That’s why we need laws — the only way we can make these people stop is to make them pay out of their pockets.”

Grassroots Action

It has taken more than laws, however, to help workers like Radford break into private industry in the South. All across the region, community advocates have used affirmative action rules as a tool in grassroots organizing, helping to pry open the doors of corporations and industries that exclude women and blacks.

Chris Weiss was a member of the YWCA board in Charleston, West Virginia in 1979 when the federal government handed down new regulations to make sure women and minorities were represented in federal contracts. Weiss developed a new program to train women looking for construction jobs, and she raised the money to make it happen.

“At the time there was a lot of building in Charleston with federal funds, which should have given women a chance,” recalls Weiss. “But it wasn’t until after we started the training program that I discovered there were no women in the building trades. I didn’t realize what they’d be up against. We would go around to the construction sites and the men would say, you can’t enter the union except through the apprentice program, and that doesn’t open up until next spring. It was a no-win situation.”

When Weiss threatened to file an EEOC complaint, the federal government pulled the funding for the training program. ‘That’s the point I took everything home to my attic and started an organization that they couldn’t shut down,” Weiss recalls. She called it Women and Employment, Inc.

The new group worked with more than 30 women who were qualified for construction jobs. “They would go on site in pairs so they could document each other’s stories,” Weiss remembers. “At one site the men dangled a purse and bra and said, ‘Look what happens to women who come on this site’ — the implication being that they get undressed and raped.”

Joining forces with a local group representing black men, the women took their case to court—and won. In 1982, the city agreed to hire more women on federally funded construction sites, and to use Women and Employment as a referral.

“Thirty-five to 40 women worked on the job in all,” says Weiss. “That was the first time in the history of the state that women worked on a building trades job.”

Since the early 1980s, however, Weiss and other grassroots organizers have watched as the Reagan administration cut back funding for the EEOC and its enforcement arm, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance.

“They effectively eliminated any kind of monitoring and enforcement in West Virginia,” says Weiss, now a program associate with the Ms. Foundation for Women. “It was real clear what was happening — and the employers got the message that they could pretty much do what they wanted to with impunity. The building trades and contractors started thumbing their nose at us when we would come around with women.”

The numbers bear out the slowing of progress during the Reagan-Bush era. Women raised their share of skilled crafts jobs twice as fast in the 1970s as they did in the 1980s — and the same is true for black gains in all white-collar jobs.

Scapegoats and Slowdowns

With weak enforcement of affirmative action rules, community organizing by grassroots groups like Women and Employment is more important than ever to ensure workplace diversity — especially in the midst of a recession. “In recessionary times it’s very easy to point a finger, very, very easy to say that a black or a female is taking something away from the white male,” says Peter Roulhac of First Union Bank in Miami. “You look at David Duke, Pat Buchanan ... it’s very easy to find scapegoats.” In truth, the Southern white male has not lost his advantage in the job market. He still occupies a vastly disproportionate share of the good jobs, and continues to receive preferential treatment from personnel managers who generally share his skin color, gender, culture, and personal mannerisms. Although white males make up a smaller percent of the total workforce than they did in 1970, the increasing number of jobs in the region means they still enjoy lower unemployment rates and higher pay.

As the recession has deepened, blacks and women who were the last hired are often finding they are the first fired. Advocates of affirmative action say many businesses are simply using hard times as an excuse to lay off workers.

“I have sensed that affirmative action had been receding before the slow down,” says Maxie Broome, a Jacksonville attorney and former chair of the Florida Black Business Investment Board. ‘The slowdown is just an excuse for not aggressively pursuing affirmative action. I’m not saying it’s a devious kind of thing. But the first thing to go is the luxuries — and affirmative action has always been viewed as a luxury by these companies.”

In the end, advocates say, the only way to truly diversify private industry is to expand the number of job opportunities available for all disadvantaged workers. “We need to retool affirmative action to address the realities of the 1990s,” says Clint Bolick, director of litigation at the Institute of Justice in Washington, D.C. “We must provide basic skills and literacy training, day care, mentoring, transportation of inner-city residents to suburban jobs — action that is truly affirmative.”

But if affirmative action is to work, then the federal government must renew its historic commitment to ensuring fair employment for all workers in private industry. “The federal government played a clear role in opening up job opportunities and eliminating discrimination in this country, and they clearly backed off from it,” says Chris Weiss. “If we’re going to see changes in the future, we’re going to have to see a stronger federal role for ensuring equal opportunity for all Americans.”