Bonnie Ledet

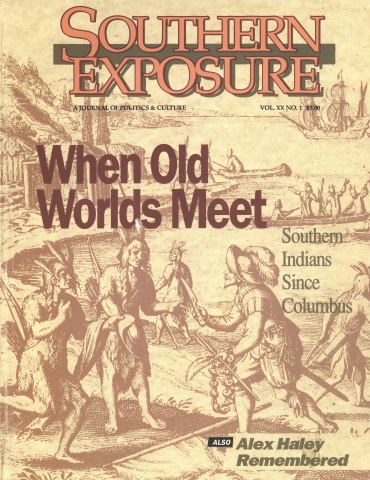

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 20 No. 1, "When Old Worlds Meet: Southern Indians Since Columbus." Find more from that issue here.

I had dragged the box full of toys from the garage onto the driveway and was dividing its contents into three piles — keepers, junk, and Salvation Army. Deep in the box I was finding things that went back to when my older brother had lived at home, back to when I was much younger than thirteen, what I was at this time. I pulled out a cracked New Orleans Saints helmet, a ragged Davy Crockett coonskin cap, and two large tin cans with straps which we had used as Steve Canyon rocketpacks. My father had told me he was tired of clutter around his work counter. He was irritable when working the three-to-midnight shift, but I usually liked this shift because it left my mother and me alone to go out for milkshakes or play Chinese checkers or just talk. Lately, though, we hadn’t done many of those things because she was still recovering from an illness which had put her in the hospital and kept her bedridden for a month.

I laid the tin cans on the junk pile, then saw three kids, a boy and a girl about my age and a younger boy, coming across the yard next door. We lived in a small neighborhood in Baton Rouge where news traveled fast, but these kids were new and I wasn’t sure where they had come from. The older boy led the way, smiling and smoking a cigarette. He wore an Army shirt with cut-off sleeves. Blackheads peppered his face.

“I’m Blane,” he said, his Cajun accent so heavy it took me a second to understand his words. “This my little brother Roland and my sister Bonnie.”

“I’m Jeb,” I said.

Roland was shorter and chunkier than Blane, and stood with his hands plunged into his pockets, his shoulders slumped. As he stared at the toys on the concrete, his eyebrows slanted in a frown toward the bridge of his nose.

The girl, Bonnie, hung back, wiry inside a faded paisley summer dress. Her short black bangs were pulled to the side and held by a plastic barrette. Her nose was pointy, her cheeks sunken below high ledges of bone. Now that she was nearer, I saw that she was probably the oldest of us.

“Our old man and us, we just moved in,” Blane said, then ground his cigarette on the drive.

“My momma won’t like it if you smoke around here,” I said.

“That’s cool,” he said, and pointed at my basketball lying on the grass. “You mind if I shoot?” he asked. “Roland, he ain’t good as me.”

“Kiss my ass, Blane,” Roland said.

He and Blane started shooting, their movements awkward and foot heavy. Bonnie stood about fifteen feet away, hugging her waist as she inspected my house and yard, her head slightly tilted toward the ground as though she were afraid of getting caught.

“Where are y’all from?” I asked her.

She looked sideways at me, her eyebrows arched. “Dulac.”

“Where’s that?” I said.

She rubbed her forearm and bit her lip.

I asked, “Is it close to New Orleans?”

“It’s down by Houma. Close to the Gulf.”

“I’ve never been to Houma.”

Blane yelled, laughing, and bounced the ball hard off Roland’s head. Roland ran after him, but Blane held him at arm’s length.

“Fucker,” Blane said. I thought they were about to fight. Bonnie sat and crossed her legs in the thick, early fall grass. Her skirt slid midway up her thighs, pale and muscled. She plucked blades of grass and tossed them to her side in small, violent movements until there was a fist-sized divot in front of her.

“When did y’all move in?” I asked.

“Yesterday,” she said.

“Where was the moving van?”

“Why you need to know?”

I shrugged. “Just asking.”

I heard the front door open behind me, my mother coming out to sweep the porch. Bonnie stood, smoothed her skirt over her thighs, and touched her fingers to her barrette.

“Blane, Roland, time to go,” she said.

“You go on,” Blane said.

“Daddy ain’t gonna like it, we not there when he gets back.”

“Fuck Daddy.” The sweeping stopped. I stood.

“Blane,” Bonnie said. “Don’t get me in trouble.”

Blane spat into the grass. They started home.

“Come by and get us for school,” he said to me. “We live around the corner.” Bonnie was already walking away, her hands clenched at her sides. With each step she took, the curve of her hips showed through her dress. At the comer Blane saluted, then punched Roland in the shoulder, but Bonnie didn’t look back.

“Who were they?” my mother asked, close to me, her arms crossed. Her hair rose in a bouffant, a style she’d started after her illness. She thought it made her face less gaunt, but it only brought out the circles under her eyes.

“They just moved in one of the rent houses,” I said. “They’re coonasses.”

“Don’t say that word,” she said.

“Mr. Badeaux says it.” He was our next-door neighbor.

“It hurts people’s feelings. You don’t say it.”

She knelt next to the pile of junk on the driveway and picked up a toy-car garage whose rusty decks were concave from where I’d sat on it when I was two. Momma ran her fingers over the surface, blue veins standing on the back of her hand.

“I remember the look you had on your face,” she said, smiling. “You thought crushing this was the cutest thing. I wish your daddy didn’t want to throw these out.”

“I’m just throwing out the broken ones. I’m keeping all the good things.”

She stood and scratched the place on her hand where small blood clots still lay beneath the skin. The doctors had thought the rash was an allergic reaction to insect repellent Momma and I had used at a drive-in movie late that summer, but later we realized it had been the first sign of her lupus. She moved her hand against the grain of my hair, then down my face to my neck. She squeezed, the ends of her long nails slightly digging in. It was an odd way for her to touch me, and I recoiled a little.

“I want you to keep that,” she said, and pointed at the crumpled garage. “I know it’s trash, but it makes me think of when you were younger.”

The next morning I walked to school between Bonnie and Blane. Bonnie wore a brown dress that fit too tightly everywhere except underneath her arms, where I could see her beige brassiere. Blane smoked a cigarette and asked if there were any girls in the neighborhood, if I had a friend with a car, if I’d ever been drunk.

“My brother gave me some wine once,” I said.

“I been drunk about a hundred fucking times,” Blane said. “I get drunk all the time.”

“You lying, Blane,” Bonnie said.

“No, I ain’t. I love to get fucked up.”

“Quit saying that word,” she said. Blane leaned over and gave me a mock whisper. “Bonnie think she our momma.”

“Shut up, Blane. You ain’t funny.” Bonnie hugged her notebook. The morning sun exposed a light sideburn of down on her face.

“Check it out,” Blane said, pointing. Up ahead was the Stop N Go parking lot where boys with homemade ink tattoos and long hair and girls in hip-hugger jeans smoked cigarettes before school. “See y’all,” Blane said, and headed off.

“Blane,” Bonnie said. “Daddy wants you to go to school.”

“Y’all tell me about it later.” He winked at me.

Bonnie’s jaw muscle flexed. “You know them people?” she asked me.

“Some of them. They go to school sometimes.”

“Blane always looking for trouble. Something loose in his head.”

I laughed, and after a second Bonnie smiled.

“I wish Blane didn’t say that in front of your momma yesterday,” Bonnie said. “She’s pretty.”

“She was real sick a month ago. She had to quit her job at Penney’s.” I remembered her in the hospital, her face so puffy her eyes were slits, her skin so sore I could only touch her hair.

“She’s well now?”

“She’s better. She still gets tired. Her skin hurts her, too.” I was about to ask about her mother, but a girl screamed and ran past us, a boy making monster grunts chasing her until the crossing guard halted them at the comer. Bonnie covered her mouth and laughed, her eyes wide. It was the first time she’d seemed my age.

In Louisiana History, Bonnie sat in the row next to me one seat ahead. While the teacher lectured about explorers, I noticed how in profile Bonnie’s chin and nose curved ever so slightly toward each other as if trying to touch in front of her lips. I traced the swell of her calf, studied the movement of her shoulder blades beneath her dress, followed the lay of the fine, dark hair on her forearms. Her body was older than most of the other eighth-grade girls, and when she leaned and reached inside her desk, I saw the cone of her bra pointing away.

After school we walked to her house. She stopped at the end of the driveway. I was hoping she would ask me in, but she stood until I asked if we could sit on the porch. Her eyebrows dipped together, and she did a slow take on her house as though she expected to see someone she hadn’t seen before. Then, without speaking, she walked to the cement steps, sat, and pulled her knees close to her chest.

“Your momma didn’t move down with y’all, did she?” I asked.

“She died when I was nine,” Bonnie said, then watched to see my reaction. “I had to stay home, take care of Roland cause Daddy was gone so much.”

“Is that why you’re in eighth grade?”

“Yeah, that’s why. Something wrong with that?”

“I just thought you were older than me, that’s all.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I thought you meant something.”

“Why was your daddy gone?”

Bonnie focused on the ground, moving her eyebrows up and down as if working the words into her mind. “He had a boat,” she said slowly, not looking at me. “One of them big fishing boats people pay to go on.”

“Cool,” I said. “Does he still have it?”

“It got tore up in a storm. That’s why we had to move down here.” She rocked back and forth, then stood. “I got to get dinner.”

“You mind if I ask you something?” I said. She shook her head. “What happened to your momma?” Her gray eyes pierced me. “I’m just wondering.”

“She drowned. She was out on the boat and something happened. She got knocked over the side.” “Really?”

“You don’t believe me?” “I believe you. It sounds terrible.”

Bonnie unlocked the door.

“Was your daddy there?” I asked.

“He didn’t see it. They didn’t find her.” She turned the doorknob.

“You mind if I ask you something else?”

“Depends on what it is.”

“Do you ever get mad at her?”

“At my mother?” She searched the porch as if she’d dropped the answer. “I used to. Once in a while, I guess. It was a long time ago.” She disappeared inside.

I looked at the grainy concrete of the steps. I thought of my mother dead, covered with a sheet in her bedroom. My mouth went dry.

At home I found Dulac in the atlas, a tiny circle near the end of a thin map road far south of Baton Rouge.

“What’re you looking at?” Momma asked, laying a hand on my shoulder. Her nails were dark red.

I pointed at the map. “That’s where Bonnie’s from.”

“That girl from yesterday?”

“Yes, ma’am. I walked to school with her. I like her.”

“Have you been down at her house?” I nodded. Momma took her hand from my shoulder, stepped around to my side. She had on a brightly flowered blouse I hadn’t seen in a long time. She clicked her nails on the tabletop. “Were her parents there?”

“Her daddy wasn’t. Her momma’s not alive anymore.”

Momma’s blue eyes widened for a moment. “How old is this girl?”

“I think she’s almost fifteen. She’s in my grade, though.”

Momma touched her throat. “Well, I don’t want you in that house when her daddy’s not home.” “We were just on the porch.”

“I said in the house.” Momma put a hand to her temple. She shut her eyes.

“You okay, Momma?”

She patted my shoulder. “I’m just tired. I went through my closet and got rid of some of my drab clothes.” She posed a moment like a model, showing off her blouse, then touched her forehead. “I think I’ll laydown a little while. Maybe later we can go get a hamburger.”

After she left the room, I stared at the atlas again. I imagined Mr. Ledet’s boat, a sleek yacht with Bonnie standing near the bow, her hair blown back, a school of dolphins leaping from the water. After a while I tiptoed down the hall to Momma’s room and peeked in. She lay flat on her back, her arms at her side, her mouth open, snoring. I wanted to turn her on her side. Instead I sat on the wooden floor and thought of being on that boat with Bonnie, its sharp prow cutting the green waves as we headed from shore.

I waited for Bonnie after school, scheming to get her to invite me inside her house. Over two weeks had passed since we had met, and even though we had been walking to and from school every day, I still hadn’t been further than her porch. I was thinking maybe I could start coughing and tell her I needed some water when a familiar car horn sounded. Parked in the circular drive behind the last school bus was our Galaxie 500, my mother waving to me as kids strolled past. I glanced to see if Bonnie had come out of the building yet, then walked over.

“What are you doing, Momma?” I asked through the passenger window. Thick make-up gave her face an unnatural beige color. Heavy streaks of rouge angled like warpaint across her cheeks.

“I was out shopping, and I thought I’d take you and your friend to the bakery.” She hadn’t taken a friend and me to the bakery since fourth grade. Bonnie came out, and I waved to her.

“I don’t know, Momma. I kind of wanted to walk.”

“It’ll be fun, Jeb. Plus I’ll get to meet this Bonnie you’ve been talking about.”

Bonnie stopped several feet from the car. I told her what was happening.

“I better not,” she said. “My daddy’s supposed to be home early.”

“It won’t take long,” Momma said. “I can explain it to him. Here, y’all get in the front.”

Bonnie exhaled through her nose, then slid onto the seat between Momma and me. In the car my arm and leg tingled against Bonnie’s, but she stared straight ahead. The odor of Momma’ s hairspray filled the car, and I kept my nose to the window, wondering if Bonnie would think my mother taking us to the bakery was queer. When we passed the Stop N Go, we saw Blane kissing a girl in a purple tube top.

“Has Jeb told you anything about me?” Momma asked, smiling.

Bonnie glanced at me. “He said you been sick.”

“He did?” Momma said, her smile leaving. “Well, I’m as good as new now. I’m going to get another job soon.” She turned on the radio and hummed along until we reached Delmont Pastries. Momma ushered us in, then stood slowly scratching the back of her hand as she examined the cakes and pastries on display behind the glass counter.

“Jeb, Bonnie, come see,” she said.

I touched Bonnie’s hand, and we walked over. Momma pointed at a cake with buccaneers and a wooden ship on top.

“Remember your pirate birthday?” Momma asked. “We put your presents in a treasure chest and had chocolate that looked like gold coins.”

“Let’s get something, Momma. Bonnie needs to go home.”

Momma ordered three chocolate eclairs, and we sat at a small table. “Jeb told me your daddy came here to find work,” Momma said to Bonnie. “What did he do down there?”

I had already told Momma what Bonnie had said, and I hoped she was making small talk, but her tone made me shift in my seat.

“He worked some different jobs. He worked on drilling rigs sometimes.”

I set my eclair on my plate. “And your mother passed away?”

Bonnie cut her eyes at me. “She died in a car wreck. Her and my daddy was out one night.”

“I know that’s hard,” Momma said. “My mother died when I was a little girl. My older sister raised me. You must be very strong.” Momma laid a hand on my wrist. “Did Jeb tell you he took care of me when I was sick?”

“Momma,” I said.

“Sorry,” she said. “But it’s good we’re close. A lot of families aren’t.”

Bonnie pressed a napkin to her lips. “I got to get home,” she said and pushed her chair back.

“I can drive you,” Momma said, but Bonnie was already going toward the door. “Go catch her,” she said to me.

“Why’d you ask those questions?” I said. “I already told you about all that.”

Momma wiped her mouth, leaving a red stain on the napkin. “I didn’t believe what she told you,” she said.

“You wanted to catch her in a lie.”

“I wanted to hear it myself.”

I wheeled and went out after Bonnie. As I crossed Winbourne Avenue I heard Momma call my name, but I didn’t look back. Bonnie was striding across the school ground. When I fell in beside her, she didn’t look at me. I wanted to apologize for my mother, but seeing Bonnie’s frown made my anger shift to her.

“Why’d you lie?” I said.

“I got to get home,” she said. “My daddy don’t like me being late.”

“Tell me why you lied.”

She stopped and faced me.

“I like what I told you better. It ain’t no big deal.”

We walked again, a little slower. Momma slowed as she passed in the car, but when I wouldn’t look at her, she drove away.

“Your momma don’t like you with me,” Bonnie said. “Why’d you tell her what I said?”

I almost told the truth, that I eventually told Momma most things that happened to me, but I didn’t say anything. Neither of us spoke again until we stopped in the street at her house.

“Why don’t you ever ask me in?” I said. Her daddy’s green Malibu sat in the driveway. Her jaw muscles worked in and out.

“Daddy don’t like nobody in the house,” she said. “Maybe when he’s gone.”

“I want a glass of water,” I said.

The screen door opened, and Mr. Ledet stepped onto the porch. Khaki pants were all he had on. He was short and stocky, his muscular chest black with hair. He had Bonnie’s pointy nose. He held a cup of coffee in his hand. Half of his index finger was gone. “Bonnie,” he said, but it sounded like “Bon A.”

“I got to go,” Bonnie said. At the door she had to duck under her father’s arm. His eyes went right into her. Mr. Ledet sipped from his cup, his face expressionless as he looked at me. “You go home,” he said, then went back in.

I walked fast, away from the Ledets’ house and ours, toward Hurricane Creek, a deep drainage ditch that snaked through our neighborhood. When I was younger, I used to go there almost every day during the summer to catch tadpoles or explore the huge dark pipe that ran beneath the road.

I shimmied down the steep side and sat on the slanted concrete near the bottom. A stench hovered above the stagnant water. The mouth of the pipe was snarled with trash —tree limbs, a broken chair, a deflated football—washed there by the rush of storm water. I hurled a chunk of concrete into the water. A week after Momma had come home from the hospital, her fever had returned, rising even after I’d put cold cloths on her and given her aspirin. I had wanted to call Daddy at work, but Momma said he’d missed too much work already, and I held her head as she vomited into the crescent shaped pan, the acid odor burning my nose. Her flushed face went pale, even the raspberry welts, and I kept talking to her, stroking her hair, hoping she would open her eyes again. When she finally looked at me she said, “Goddamn this. Goddamnit, I thought I was okay,” words like none I’d ever heard from her, words which made me certain she was going to die.

I was dribbling my basketball a few days later when Blane came up the driveway, smiling, a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

“You know where Roland at?” he said. “His school called Daddy at work, said Roland beat up some kid. Daddy mad as hell.” Blane flicked ashes, then cupped the cigarette to hide it.

“I haven’t seen him,” I said.

“Boy must’ve fucked with Roland. Roland don’t start things. He finish ’em, though.”

“There he is,” I said, and pointed at Roland, who was coming out of a clump of tall hedges across the street two houses down. His thumbs were hooked in his pockets, his jaw shoved forward.

“Shit, he was hiding,” Blane said. “Roland, you was in them bushes?”

“I was thinking,” Roland said.

“What that boy did to you?”

“Told me I couldn’t read.”

“Daddy gonna whip your ass,” Blane said.

“Shit on Daddy,” Roland said. “Give me a cigarette.”

“Jeb’s momma don’t want us smoking here.”

“How long are you suspended for?” I asked.

“A whole fucking week. Principal say she going to teach me to act good. I told her I still ain’t taking no shit.”

“Boy, Daddy gonna hit you,” Blane said. “Bonnie ain’t gonna be able to stop this.”

Roland stared straight ahead, tears welling up, then walked off toward their house. Blane wiped a fake tear for my sake, then went after Roland. Blane nudged him, tried to put an arm around Roland’s shoulder, but Roland blocked it.

“Jeb, come here a minute,” my mother said from the backyard corner of the house. Her left hand was covered with black soil, her right hand held a small rake with three claws. She’d been turning dirt in her garden and had overheard everything we’d said. I banked a shot in, then slapped the ball into the grass before I walked to her. It was a warm day, and there were pink splotches on her face as though she had fever again. Her blouse stuck in wet patches to her chest and the tops of her breasts.

“I don’t want you near that house anymore,” she said. “It’s not good for you.”

“You don’t like Bonnie, that’s it.”

“She doesn’t have a mother. Most of her life she’s been by herself with those boys and a man who hits them. That girl knows a lot more than you do, Jeb.”

“That’s why I like her.” She pointed the hoe at me. “I’m telling you not to go down there. End of talk.” She walked back to the garden, lowered onto her knees, and stabbed the dirt.

“You can’t stop me,” I said.

She looked up. “I’m your mother,” she said.

“Then why don’t you act like it?” She narrowed her eyes at me and started shaking. I took a step forward, wanting to take back what I’d said, but I didn’t. She scooped up dirt with her free hand and crumbled it. “Leave me alone,” she said.

The next morning I waited in front of Bonnie’s house past the time when she was supposed to show. The Malibu was in the driveway, but I knocked anyway. After the third knock, I heard heavy footsteps and moved back a little, bracing for Mr. Ledet. The Venetian blinds on the front window rattled, a dark slit opened and closed, then the footsteps receded. I made a fist to hit the door once more, then jumped off the porch and stormed toward school.

That afternoon, Bonnie was on her porch, wearing shorts and a low-cut shirt that showed freckles on her chest. Tied on her head was a red bandana which hid her hair and caused her eyes to stand out from her face when she pulled on her cigarette, something I’d never seen her do.

“Daddy said don’t bang on the door.” She pressed the arches of her bare feet together.

“Why didn’t you answer? I wanted you to go to school.”

“I ain’t going to school no more. It’s stupid. What you learned there?” Bonnie struck a match, raised it near her eyes, blew it out. “Your momma’s jealous.”

“No, she ain’t. She’s my mother.”

“So?” Bonnie took a last drag, then thumped the cigarette into the yard.

“Is your daddy here?”

“Work called him at noon.” She tugged at the legs of her shorts. On her thigh I saw three bruises, each the size of a fingertip.

“Where’s Roland?” I asked.

“Daddy ran him off hitting him.” She examined my face. “You want to come in?”

“Inside your house?”

She laughed and stood. Their house was hot and stale, without the exotic smells of rouxs and etouffe and fried garfish like those at our neighbors, the Badeauxs. In the living room was a portable TV and a worn vinyl recliner with strips of silver duct tape on the seat. The walls were blank except for a framed photo of the family when Mrs. Ledet was still alive. Bonnie’s mother looked like Bonnie except with a more rounded face. She looked younger than my mother, and I touched the glass without thinking. When I turned Bonnie’s lips were tight.

“You want some water?” she asked, and walked off. While Bonnie was in the kitchen, I wandered down the short hall. Through an open door I saw her father’s room, his queen-sized bed covered by a tangle of sheets, four pillows twisted and crushed. Bonnie brushed past me, shut the door, and handed me my water.

“This is my room,” she said, leading me across the hall. The only furniture was a wooden chair, a single bed without sheets, and a small chest-of-drawers. On top of the chest sat a round hand-held mirror, a pair of scissors, and a bottle of rubbing alcohol. On the floor lay clumps of hair.

“You cut your hair?” I asked.

“No, it just fell out.” Bonnie unscrewed the lid of the rubbing alcohol, sniffed it, and recoiled. “You want a sip?” she asked, then shoved it under my nose, but I pushed it away. She closed the bottle and dropped it back in the drawer.

“Let me see your hair,” I said.

“Why should I?”

“I want to see what it looks like.” She took a transistor radio from one of the drawers, turned it on and moved across the room. “Your daddy ever hit you?”

“He used to whip me with a skinny belt,” I said.

“Where he hit you? On the ass?”

I nodded. “Did your daddy hit you?”

Bonnie snapped her fingers to the music.

“You like to dance?” she asked.

“Dance?”

“Come on.” She grabbed my wrist and pulled me across the hall into her father’s room, my glass sloshing water. A basket of dirty work clothes reeked of sweat and chemicals. Next to the basket lay a white nightgown and some girls’ underwear. When I looked at Bonnie, she had the radio pressed to her chin, her fingers white from gripping it so hard. She snatched the glass from my hand and made me stand on the bed with her. She turned up the music, kicked the covers and pillows to the floor, squeezed my wrists, and bounced. I grasped her hands and we flew, our heads almost touching the low ceiling, the bed creaking as Bonnie’s wild laughter spilled over me. As we jumped I spun us, and we turned a slow circle, gripping each other tighter.

Suddenly she stopped, put a hand to my mouth, and turned off the radio. Down the hall came footsteps. Blane stuck his head around the comer.

“What you doing?” he asked Bonnie. “You know it ain’t cool Daddy catch him in here.”

“Shit on Daddy,” Bonnie said.

Blane flung his hair away from his glassy eyes. “Where Roland went?”

“He left this morning,” Bonnie said.

“Damn. Where Daddy at?”

“He went to work. Leave us be.”

Blane smiled at me. “Don’t let my old man catch you,” he said, and knocked twice on the door frame. We heard him slam the front door.

“I know Blane stoned,” Bonnie said. “I hope Roland don’t start that.” I stepped off the bed, but Bonnie stayed. She touched the depression at the base of her throat. You like me.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I like you a lot.”

She put her hand on my shoulder and hopped down. Her hand still on me, she reached with the other and removed her bandana. Her hair was mutilated, the same length as before in some places, her scalp visible in other places, as if someone had ripped out hanks of it.

“Your daddy did that?” I said.

“I did it. To show him. You like it?”

“No l don’t like it. Why did you do that?”

She looked at the bed, then jerked her head as though she’d been slapped. She took my hand and ran it over her head, the bristles sharp, the longer hair soft and fine. The bandana was still knotted, and she slid it onto my head, her thumbs pressed to my temples.

“You ever kiss a girl, Jeb?” she asked.

“Not really.”

“You want to kiss me?”

I nodded. She placed her mouth on mine. When her lips opened, I opened mine too, let her tongue, thick and dry, come inside, the taste of cigarettes bitter and sharp. The second time I tried to use my tongue, but she took a step back, glanced over my face as if looking for some small thing, then gently pushed me so that I sat on the bed. She sat sideways on my lap. I put my arms around her and hugged her, the small circles of her breasts against me, the warm skin of her cheek on mine. “You can touch me,” she said, and I slid my hands under her shirt, over the tense muscles of her back and the knobby ridge of her spine. Her breathing was loud and close to my ear, and I felt wild and bigger than I was, moved my hands up to her shoulder blades, then around to her breasts, firm and soft at the same time, like nothing I’d ever felt. She made a slight noise like pain and gripped me tighter, but her cheek moved from mine and she stood by the bed.

“You got to go,” she said, and a bolt of lightning went through my head.

“Is somebody here?” I asked. There was a swirl around her. She took the bandana from my head, put it back on hers and went to her room. I followed her, but she kept her back to me.

“You didn’t like it?” I asked, confused, thinking there was something I should do, but only wanting to touch her again. I took a step toward her, and she turned and pointed two fingers. “Go on,” she said.

“Your daddy made those bruises on your leg, didn’t he? He hit you like he hit Roland. I want you to come to my house.”

Bonnie smiled, hugging herself, but it was a smile close to crying. She put her hands on her head. “I did this. I took my scissors and did it. That fucker’s gonna see. Get on out.”

As I went down the hall I heard her start crying. The feel of her skin and hair was still on my hands, the taste of her mouth still in my mouth. I walked out of her house and down her street toward mine, the world around me shut away as though I were in a tunnel. Inside our garage I stopped. Through the wall came the muffled babble of the TV like a voice beneath a blanket. I imagined Mr. Ledet’s hand swinging hard against Bonnie’s face. He pushed her to the floor, his hand gripping her thigh, his heavy body on top of hers.

I threw a punch into the wooden wall, then another and another, then I was kicking a metal gas can and plastic jugs of toluene, punching the wall again. “Stop it!” I heard Momma’s voice yell and her hands pulled my arms, but I flung them off and kicked the washer, the hollow metal booming until she grabbed my shirt.

“Leave me alone!” I said, jumping back. “Don’t touch me!”

“You stop it!” she said and held out her flattened hand as if to strike me. She balled her fists. “You’ve been at her house!”

I backed away. “What’s wrong with you?” I said. “Quit it. You’re scaring me.”

She stopped. She opened her fists and raised her hands in front of her. There was disgust on her face. She walked over to the steps by the kitchen door and sat. She looked tired, as if she’d been running ever since the rash had bloomed on her.

My hands were bruised and bleeding, my arms quivering. I walked over and sat next to her. After a minute she touched my hands with her fingertips.

“We need to put something on that,” she said, but we didn’t move.

Before school the next morning I knocked at Bonnie’s, even though the car was in the drive, then did the same again that afternoon. Later that night, after my father had come home and gone to bed, I snuck out to Bonnie’s house, the night humid and cool. Mr. Ledet’s car was still there. The porch light was off, but the inside lights burned yellow through the blinds. I listened beneath the high windows on the side of the house, but all I heard was the distant sound of traffic.

The following day I knocked again, but when no one answered, I banged, twenty or thirty times. Blane jerked open the door. He was in his underwear. One eye was cut and swollen. “Shit! What you want?” he asked, a hand laid flat on his ribs.

“Jesus. Your old man did that?”

“You always asking questions.” He rubbed a hand over his face. “I tried to stop him hitting Roland, so he switched off.”

“You hit him back?”

“I tried. He’s a tough fucker.”

When I didn’t say anything, he motioned me inside and led me to the kitchen. The linoleum floor was cracked and peeling. Blane turned on the burner beneath the coffee pot.

“You drink coffee?” he asked. I shook my head. “Bet my old man wish he didn’t.” He took an apple from the fridge, cut it with a thin-bladed filet knife and gave me half. We sat.

“Where’s Bonnie?” I asked.

“At the hospital.”

“She’s hurt?”

“She’s with Daddy.” He smiled. “You fucked her?”

“Shut up, Blane.” He laughed, then grunted like an old man when he stood to pour the water.

“Did you hurt him when you hit him?” I asked.

“No, man. Bonnie put rubbing alcohol in his coffee. Fucked him up.”

“Is he going to die?”

“Nah. He’s too mean to die.”

Blane took a cup from the sink and turned on the hot water. He scrubbed the rim with his finger. “Does he know Bonnie did it?” I asked.

“She told him. His stomach cramped real bad, and when the ambulance pulled up, she said she wasn’t gonna take him messing with us no more.” Blane poured the coffee into his cup. We each ate our apple half until Blane looked at me with the most serious expression I’d ever seen on his face. “You know my old man and Bonnie do it,” he said. “That’s why we had to move here. Neighbors found out. The sheriff told Daddy to go.”

I tossed the rest of the apple into the garbage. Roland came in and sat with us, his face relaxed, the most like a kid’s since I’d met him. “How you like Blane’s new face?” he asked me. “You shoulda seen how bad he thought he was till Daddy knocked him.”

“Saved your little ass,” Blane said.

“Blane told you what Bonnie did?” Roland asked. “Too bad she didn’t kill that bastard.”

Blane sipped his coffee and stared at the wall like he hadn’t heard Roland. He had lit a cigarette, but it was already halfway burned in the ashtray, and he hadn’t touched it.

“Why did she go to the hospital with him?” I asked.

Blane looked at me from the corner of his eye as though I’d asked the most ridiculous question. “Cause he’s our daddy,” he said.

How are your hands?” Momma asked. It was before school two days later. She hadn’t said anything about the Ledets since I had punched the wall. I held out my bruised knuckles. She laughed. “You better be glad your daddy didn’t see you trying to knock a hole in his garage.”

“Thanks for not telling,” I said.

“I’m going job hunting today,” she said. “Being around this house all the time’s making me crazy.” “You look pretty,” I said, and she me gave a smile. “Daddy knows you ’re looking for a job?”

“We talked about it last night when he came in. I guess that’s why he’s still asleep—I kept him up so late.” She lifted her coffee cup with both hands, blew on it, and sipped. “He starts days soon, and you and I haven’t even gone out for a milkshake.” She sat back. “Have you seen Bonnie?”

“She hasn’t been home.”

She waited for more, then nodded. “It’s confusing sometimes, isn’t it?” She forced a smile, then stared at the table.

I downed my juice and said, “I’ve gotta go.”

“I could drive you,” she said, but I didn’t answer. I wanted to talk to Momma about Bonnie, wanted to tell her that Bonnie had carried them all — Mr. Ledet, Blane, Roland— had carried them without any of them knowing it, maybe without knowing it herself. I kissed Momma, and she hugged me before I headed outside.

The last two days no one had come when I knocked on Bonnie’s door. This morning it was ajar. I eased inside and called out, but my voice rang through the house and died without answer. In the living room a few dust balls were all that remained. I went down the hall to her father’s room, the morning light harsh through the uncurtained windows, the smell of his clothes still heavy. I remembered Bonnie and me on his bed, her lips on mine, my hand on her hair. In a way it seemed a long time ago. I looked in his empty closet, then crossed the hall. I stood in the center of Bonnie’ s room and breathed in. I walked to the corner where her chest-of-drawers had been and knelt on her floor, hoping to find something, a button, a string, a bit of her hair, but every trace had been swept clean.

Tags

Tim Parrish

Tim Parrish lives in Tuscaloosa and teaches at the University of Alabama (1992)