Waste Busters

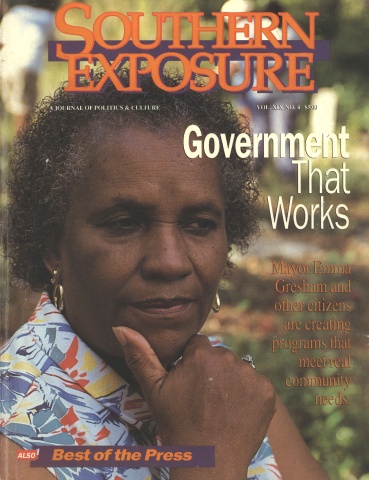

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Tallahassee, Fla. — Newspapers looking for flashy headlines call them “envirocops.” Corporate polluters call them “dump wardens.” But most Floridians aren’t concerned with what they’re called. They only hope the new state Environmental Enforcement Section can save what’s left of Florida’s fragile environment.

Established in 1989 as a bureau of the state Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, the Environmental Enforcement Section (EES) is designed to respond to an onslaught of pollution that threatens the land and water. Its mission: take hazardous waste criminals to court and make them pay for their environmental crimes.

In their first two years on the beat, the envirocops have handed out 2,200 citations and chalked up a conviction record of 90 percent. The initial success of the environmental police force demonstrates how states can take action to protect their natural resources — without writing more laws, and without spending more money.

In Florida, the need for tougher enforcement of pollution laws stems from the population boom of the past decade. Nearly 1,200 people move to the Sunshine State every day to carve out their piece of paradise. Over 13 million now inhabit the state, with an additional three million projected to join them by the year 2000 — an annual increase equal to the population of Tampa.

The dramatic influx of new residents has meant more roads, shopping malls, office buildings, and homes — developments which threaten critical wetlands, destroy wildlife habitat, dry up groundwater supplies, and produce a staggering 45,000 tons of solid waste each day.

Unlike other officers with the game and fish commission who concentrate on nabbing small-time poachers, the new envirocops have bigger fish to fry. “The commission has realized that the greatest detriment to fish and wildlife is habitat destruction,” says Sergeant Lou Roberson. “That will destroy more fish and game than any hunter every could.”

And while other state agencies get bogged down in lengthy hearings and bureaucratic detail, the EES is strictly a criminal investigative unit. Its 39-member team is designed to fill a gap between administrative agencies and the courts. Once officers find evidence of environmental crimes, they build a case and haul the polluter before a judge. Their record on criminal dumping of solid and hazardous waste has been especially successful — violators are often forced to cease illegal dumping, pay stiff penalties, and restore the damage they’ve done.

That means getting tough on polluters like Edward Fisher. Last year, the Inverness businessman contacted the landlords of two vacant storage areas near Tampa and arranged to rent their spaces to temporarily store discarded tires on their way to be shredded for disposal. During the next month, tires streamed into the two locations as planned.

The problem came when the rent checks Fisher wrote to the landlords bounced. The owners visited the sites and discovered more than 20,000 tires stacked to the ceilings. Fisher was nowhere to be found.

Threatened with having to pay for removing the tires, the two landlords contacted the EES for help. Investigators tracked down Fisher, arrested him, and charged him with commercial littering — a felony under Florida law. He was sentenced to three years probation, required to perform 200 hours of community service, and ordered to pay $10,000 to clean up the mess.

Such decisive action comes from looking at environmental crime from a different perspective. “As law-enforcement officers, we have a more cynical mindset,” says Paul Hoover, staff officer for the bureau that oversees EES. We turn up things that aren’t considered or that other agencies miss. People see us in uniform and know that we’ll get more done, and quicker.”

No More Fig Leaves

In its brief two-year existence, EES has come a long way in toughening enforcement of environmental laws. But its origins are rooted in the far-reaching legal powers of its parent agency, the Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission.

Established in 1943 by executive order from the governor, the commission was charged with enforcing fish and game laws. Over the years, wildlife officers evolved into fully empowered state cops. Their fish and wildlife duties were combined with those of other police officers, giving them more power than any other state law enforcement agents.

In 1972, the federal Environmental Protection Act gave the commission even more enforcement responsibility, shifting its priorities from simply enforcing fish and game laws to managing and protecting the land and water where wildlife lives. Already overburdened officers found themselves hard pressed to enforce the growing number of laws and regulations, and environmental violations were often lost in the bureaucratic confusion.

Then came the Florida growth boom of the mid-1980s — the proverbial backbreaking straw that forced a change. A 1988 study by the game and fish commission showed that officers spent 8,000 hours on 744 cases. With the caseloads soaring, a separate enforcement unit seemed like the only solution.

Created in the midst of a state budget crunch, EES showed how a state can protect its land and water without spending more money. No new positions or personnel were required: The game and fish commission simply changed the status of 34 officers and five supervisors and reassigned them to the new team. The move allowed investigators to devote all their energy to cracking down on environmental polluters.

The officers selected for EES are veteran men and women experienced in a variety of law enforcement techniques. They must be able to slog through a swamp looking for evidence of illegal dumping, and to sit in a board room holding a corporate president accountable for pollution. They must work closely with state and federal officials, and handle the technical complexities of toxic substance removal, water quality, and chemical and oil spills. They even receive training in media relations — another way of putting pressure on environmental criminals to clean up their act.

“Years ago our officers were asked to hide under fig leaves when the media came around,” laughs Paul Hoover, who supervises the new unit. “But the day and age of being able to avoid the media is gone. Today our investigators receive training on how to deal with the media. We encourage it. It works well from an enforcement and deterrent standpoint. Companies don’t want to be publicly labeled as polluters.”

Pollution Doesn’t Pay

Such tactics are putting Florida companies on notice that environmental crime is serious business. For years, corporations have intentionally violated environmental regulations — simply budgeting funds in advance to pay the small administrative fines.

Now, polluters are beginning to realize that the stakes of illegal dumping are much higher. In addition to levying costly fines, Florida courts are tacking on stiff jail terms, long probationary periods, and community-service time. Paying fines is one thing, but going to prison is an alternative few CEOs can afford.

“I think people are finally beginning to realize that this is real crime,” says Florida Attorney General Robert Butterworth. “And the victim is a whole lot of people.”

To put even more bite into the law, EES is empowered to seize equipment and property from offending companies. In the Ocala National Forest of central Florida, a now-defunct oil transport company was caught discharging oil along the roadside. The driver was arrested and later convicted, and the company had to forfeit its tank truck. In the Florida Keys, the state confiscated more than $250,000 in heavy equipment from Key Iron Works after the company illegally dumped construction debris, creosote, and other hazardous chemicals.

No polluter seems too big for EES to confront. In Polk County, officers charged developer Louis Fischer with filling a wetland without a state permit. Fischer plans to build a huge resort on 8,500 acres in the county where six Southern bald eagles nest.

Even when EES doesn’t win its cases, it puts polluters on notice that they are being carefully monitored. In one major case, officers cited the Amtrak Corporation for dumping raw sewage in the St. Johns River. The company was found guilty on four counts of felony littering, sparking similar litigation in 22 other states. In the end, however, the ruling was overturned on appeal, allowing Amtrak to continue dumping until it develops septic holding tanks for its trains.

As with Amtrak, many of the cases EES investigates result from the most powerful tool in its arsenal: the 1988 Florida Litter Law. “The litter law was a landmark piece of legislation for us,” says EES supervisor Paul Hoover. “It was much of the impetus in setting up the unit.”

Born from a patchwork of divisive statutes, the new law became the cornerstone for all waste dumping cases. It’s been used to cite violators for illegally dumping everything from toxic chemicals to dead chickens. The law classifies violations as infractions, misdemeanors, or felonies based on how much and what kind of waste is dumped.

Under the law, illegally dumping hazardous waste, litter exceeding 500 pounds, or any quantity for commercial purposes is a third-degree felony punishable with a fine up to $5,000 and a prison term up to five years. Using a commercial vehicle in the crime automatically makes the violation a felony, and the vehicle may be forfeited.

Making major cases that stick has given EES a reputation as unbending under pressure, but taking people to court is only one solution. Randy Hopkins, head of the section, thinks success is more about preventing environmental crime than winning cases.

“We don’t measure our success by the number of arrests,” Hopkins says. “Compliance with the regulations is the issue. If we can’t ensure compliance, then we’ll go into the courts to get it.”

The Bottom Line

The success with environmental law enforcement in Florida has not gone unnoticed in other Southern states. “In a short time Florida has been able to accomplish a lot and bring in some good fines,” says Paul Oliver, director of fish and wildlife law enforcement in Kentucky. “They’ve expanded and made a place for themselves as the leading environmental enforcement agency.”

Oliver and other officials in Kentucky are developing their own specialized enforcement unit modeled on EES. Last fall, they placed environmental enforcement officers throughout the state to investigate pollution and illegal dumping. “We looked at the environmental problems Florida and other coastal states are facing and realized that Kentucky may have similar problems in the future,” Oliver explains.

In West Virginia, officials recently streamlined the Office of Environmental Enforcement, combining its water quality and solid waste bureaus into one group. Although the 48 inspectors in the unit routinely monitor hazardous waste sites, they are not law enforcement officers and lack the power to make arrests. Cases that require criminal investigation are still referred to other department divisions or to state and county prosecutors.

Slowly but surely, the tougher enforcement of environmental laws in Florida seems to be catching on. Those fighting to conserve the land and water say they are impressed to see a Southern state cracking down on companies that profit from pollution — especially at a time when the federal government is supporting developers who want to build more condos in sensitive wetlands and oil companies that want to expand offshore drilling.

Florida environmental investigator Clyde Jordan says his job gives him a chance to make a difference. “It’s a direction I wanted to take a long time ago. We can’t stop growth, but we have to minimize its impact on the environment. If we don’t watch out for it, it’s over. That’s the bottom line.”

Tags

Greg Williams

Freelance writer Greg Williams has written for Florida Wildlife and E Magazine. (1991)