Still the South: Mobile Homes

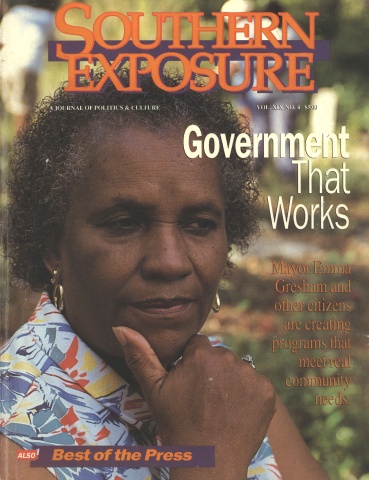

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Mobile homes have become a roadside fixture of the Southern landscape over the past half century. Originally created as playhouses for the wealthy, they have evolved into a $6-billion industry that provides one of the few alternatives to renting for millions of working families unable to afford their own home.

The mobile home dates back to the Roaring Twenties when aircraft designer Glenn Curtiss began selling luxury trailer homes called “ Aerocars” to the rich and famous. In an age of airplane frenzy, his customized “land yachts” sported cockpit observatories, trailer-to-car telephones, separate kitchens, and butler quarters at then-exorbitant price tags of $25,000.

As cars became cheaper and more accessible, a new cottage industry arose — small, inexpensive trailer homes for the middle class. During the Great Depression, homemade trailers outnumbered factory-built models by two to one. Industrial production finally gained control of the market in 1936, when the National Used Car Market Report listed 800 commercial trailer builders nationwide.

Curtiss had prophesied that if his trailer homes became readily available to middle-class consumers, they would become heavily stigmatized. He was right. Hotel and restaurant owners were outraged by the new breed of self-sufficient mobile home owners, and some even speculated that the motorized nomads were evading property taxes by moving their homes from state to state.

But it was the Second World War that transformed the mobile home into a permanent residence for many Americans. The federal government began ordering low-cost trailers for on-site worker housing, and by 1945 the mobile home offered many workers their only affordable alternative to renting.

Through the Fifties and Sixties mobile homes grew larger and less mobile. The trailer park, formerly a vacation camp ground, became a permanent neighborhood for mobile homes.

Nowhere are mobile homes more prolific than in the rural South. Like the tenant farmhouse and the shotgun shack before them, compact trailers provide a basic form of folk housing, offering economical shelter to low-income families. In mountain areas, parents often put mobile homes near the family homestead so their grown children will have a place of their own to live.

In 1976 the mobile home industry — hoping to overcome the low-rent image of its product—began a marketing campaign to change its name to “manufactured housing.” It didn’t work.

“I don’t like to hear people call them trailers,” complains Bill Clark, a mobile home salesman in Gamer, North Carolina. “Manufactured homes are as good as any stick house.”

Today the South leads the nation in its dependency on “manufactured homes” as an alternative to conventional “stick houses.” Census figures indicate that half of all mobile homes reside in the region, and six of the 10 states receiving the largest per capita shipments of mobile homes last year were Southern. South and North Carolina topped the list, followed by Alabama, Kentucky, Georgia, and West Virginia.

Most modem mobile homes resemble traditional houses, with full kitchens, living rooms, and separate bedrooms. Prices run as low as $25,000, and more expensive models include options like fireplaces, cathedral ceilings, skylights, and sunken tubs.

Yet the mobile-home stigma of poverty and tornado traps is slow to die. “Most people who come to look at mobile homes are educated about them,” says Mack McElheney, who has sold mobile homes for 30 years in Durham, North Carolina. “But once in a while someone will bring their mother-in-law, and they still think that mobile homes attract hurricanes.”

Tags

Leila Finn

Leila Finn holds a degree in anthropology and lives in Raleigh, North Carolina. (1991)

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)