"Somebody We Can Get”

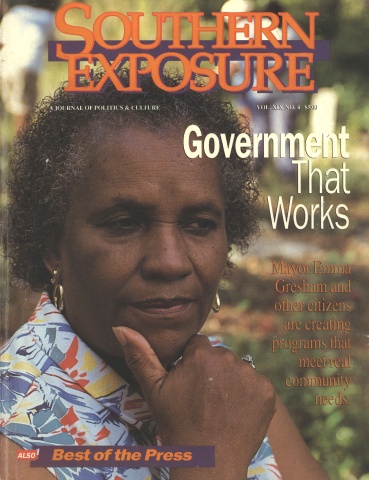

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-gay slurs.

Violence against gay men and lesbians has been on the rise in the South, jumping 27 percent last year in North Carolina. Yet most newspapers have paid little attention to brutal incidents of “gay bashing,” preferring to ignore the hatred behind the crimes.

When Ken Schell was savagely attacked in 1987, The Charlotte Observer reported the assault in a five-paragraph story that never mentioned the motive. Three years later, Diane Suchetka tracked Schell down and convinced him to tell the full story. The result is a compelling portrait of a little-discussed form of violence that is spreading across the region.

Charlotte, N.C. — Mark Barberree was out of work. He needed money the night he was drinking outside a local convenience store.

“I know somebody we can get,” Barberree told his buddy, Larry Shrader. “This guy’s a faggot. We can get away with it.”

Just before 10 that night, Ken Schell heard a knock at his Chantilly bungalow. When he opened the door, a fist hit him between the eyes. His glasses snapped and flew across the room.

Barberree, 24, and Shrader, 23, elbowed their way inside, shut the door, and slid the chain across the lock. One slammed the 42-year-old teacher into the sofa. The other drew a seven-inch hunting knife and ran the tip down Schell’s forearm until blood dripped.

“What are you doing?” Schell asked. “What’s going on?”

“We’re going to hurt you real bad and then we’re going to kill you,” Shrader said.

Then he laughed.

Anti-Gay Acts

Today, three and a half years later, Charlotte Police Officer Bob Cooke still says it’s one of the most violent crimes he’s ever seen. “I never will forget that house or that victim,” he says.

It’s one example of the violence against gay men and lesbians now surging in North Carolina and across America. Anti-gay violence and harassment jumped 42 percent in 1990 in six major American cities, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force reported.

In North Carolina, the number of anti-gay incidents rose 27 percent last year — from 1,204 to 1,530 — according to the N.C. Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality. Those statistics include two murders and 70 assaults and robberies. Not included are another 376 episodes of violence committed against gay men and lesbians by their own families.

Charlotte police don’t keep statistics on anti-gay crimes. And gay leaders in neighboring South Carolina say they know of no organization gathering statistics there.

But gays aren’t the only ones who say the numbers are increasing. In New York City, where police document crimes against gays and lesbians, they more than doubled last year. In some cases, police say men pretend to be gay and pick up gay men to learn where they live and what they own. Then they rob or kill them.

Violence against gays and lesbians is like rape. Many victims don’t report it. Because police reports are public record, gay men and lesbians fear that reporting crimes against them will make public their sexual orientation. Then they could lose their jobs, apartments, or custody of their children.

This is the story of a hate crime. The details come from interviews and court and police records. The men who attacked Ken Schell would not be interviewed.

If Schell had been attacked because he was black or Jewish, the violence would have received much more attention when it happened, says Charlotte lawyer and gay activist Chris Werte. “But gays and lesbians aren’t thought of as human beings,” he says. “They’re thought of as immoral objects.”

Coming Out

Ken Schell grew up in a working-class family in Wyoming, Ohio, a wealthy Cincinnati suburb. He knew in junior high school that he was attracted to boys, but he trained himself to turn his head “like a normal guy” when girls walked by.

He didn’t date, but he was bright — bright enough to win an academic scholarship to Earlham College in Indiana. In 1967, he graduated with a degree in biology.

That year, he moved to the Charlotte area for a teaching job, but he kept his sexual orientation a secret. Later, Schell, an art lover since childhood, helped start the Visual Arts Coalition and became president of the N.C. Print and Drawing Society.

In 1978, after a three-month relationship, he learned the man he loved did not love him. His heart was broken and he needed to talk. So at the age of 34 Schell came out. He told his family and friends that he was gay.

No one abandoned him. He couldn’t believe it.

Life was easier.

Then, one summer night in 1987, he picked up a hitchhiker. The man told Ken he was troubled and confused about his marriage. They sat in the parking lot of Latta Park for two hours talking. And when Schell got ready to leave, the hitchhiker said he wanted to go home with Schell. They spent the night together.

For the next few weeks, the man kept asking Ken for money. He called — even came to his house. But Ken always said no to Mark Barberree.

“He’s Still Breathing”

“Where’s your money?” Shrader yelled at Schell as he scoured each room. “Where’s your jewelry? Don’t you have some guns here?”

While Shrader searched for valuables, Barberree punched Schell in the face and chest again and again, pushing him into walls and from room to room. Then he shoved Schell into a bedroom and onto the bed. He held a half bottle of red wine he’d taken from Schell’s refrigerator and started splashing it on him.

“You don’t have to humiliate him,” Shrader said to Barberree. “You know we’re going to kill him in a minute.”

The men forced Schell into the living room and demanded his car keys. I’ve got to do something soon, Schell told himself. If they’re getting ready to leave, they’re getting ready to kill me. This is it.

Schell had nothing to lose. He dove through the living room window.

Three-quarters of Schell made it past the two panes of glass and the splintered window frame, but a shard of glass foiled his escape. It sliced open Schell’s leg just below his left knee.

At least the neighbors could hear him now. “Help! Murder! Help!” he screamed.

Before he could say anything else, one of the men grabbed his hair, pulled him inside, and stabbed him over and over again in the back with the knife. They pulled him to his feet and Schell instinctively blocked his face with his left arm. Barberree jammed the knife into Schell’s chest.

“You killed me,” he said as he fell to the floor. But Schell could still hear voices.

“He’s still breathing,” Shrader said calmly. “Let’s cut his throat.”

“No, let’s get out of here,” Barberree said.

“He’s still breathing. Stab in the back of the skull.”

“Let’s just get out of here.”

They lifted $23 from Schell’s wallet and ran out the door.

Schell crawled four feet to the phone in the dining room, his eyes shut tight. I know I’m going to die, he thought, but before I do, I’m going to make sure they get caught. He felt for the last hole in the rotary dial, where the O would be, and dialed.

Police arrived in minutes. Officer Cooke stepped through the broken window and let another officer in through the door. They found Schell sitting on the floor like a rag doll — his legs stretched out in front of him, arms dangling and eyes shut so he wouldn’t have to see the blood draining from the 27 stab wounds and the cuts in his body.

During the three-mile ambulance ride to the hospital, Schell never stopped talking to himself. With every beat of his heart, he repeated his mantra: “I will live. I will live. I will live. I will live.”

The Trauma Unit

At 1:15 that morning, August 25, 1987, police found Barberree, apparently passed out, face down in a dog kennel behind his house, a German shepherd lying beside him. Barberree was spattered with blood. His white high-top tennis shoes were drenched in it.

They couldn’t find Shrader.

In the trauma unit that night, doctors pumped blood back into Schell’s body. They cut him open from his breast bone to below his belly button to check the damage to his organs.

He was lucky. The knife just missed his heart, just missed his lungs, just missed his spine.

For weeks, it hurt to breathe. The incision became infected. And four times a day, Schell endured 30 minutes of torture as a nurse used forceps to pack gauze into his stab wounds.

But he was buoyed by dozens of friends — gay and straight — who came to his hospital room, put his family up, and paid for a charter plane to take him home to Ohio when he couldn’t fly on a commercial flight.

About six weeks after the assault, police arrested Shrader. He had fled to Atlanta and a tipster told police he was back in town.

Three months after the attack, Schell returned to Charlotte. There were physical therapy sessions and thousands of dollars in medical bills that insurance didn’t cover. By Thanksgiving, he was finally able to go back to work. But not without his cane.

Going Public

It is rare, given the strong anti-gay sentiment in the Carolinas, for a gay man to talk publicly about being assaulted. It’s even rarer that he allow himself to be identified. Friends have begged Schell not to tell his story, fearing for his life.

But Schell, now 46, wants people to understand the horror. He says fear is constant for gay men and lesbians.

“I’m not going to live out of fear,” he says. “For me to live my life publicly as who I am is an affirmation of who I am — the freedom that this country is all about.

“I hope other gay men will be less afraid to be who they are.”

Schell has thick graying hair and a bushy handlebar mustache. His green eyes twinkle behind black reading glasses. He has recovered, but his knee still throbs and his chest knots up from the stab wounds.

“I’m not vengeful,” he says. “But my expectation was that these guys would be put away for 50 or 60 years.”

They weren’t.

On November 13, 1987, his two assailants appeared before Judge Frank Snepp. Both, it turned out, had criminal records that included arrests for theft and assault. Shrader had been arrested for breaking a man’s jaw with a baseball bat. Barberree had been convicted of assaulting a police officer.

The district attorney’s office agreed to a plea bargain. Even with that, each man faced up to 60 years in prison. In exchange for a lesser sentence, Barberree and Shrader pleaded guilty to armed robbery and assault with a deadly weapon, with intent to kill.

Snepp sentenced each to the minimum prison term: 14 years. In North Carolina, inmates get one day off their sentences for every day of good behavior. That can turn 14 years into seven.

That, says Schell, makes him feel as though he was victimized twice. “It’s appalling to me that Jim Bakker was given a longer sentence than these guys,” he says. “I’m an upstanding, law-abiding citizen, except that I’m a faggot. If I wasn’t, I have no doubt they would have received longer sentences.”

Snepp, who retired in 1989, says he doesn’t remember the case. “I heard hundreds of cases,” he says. “I only remember sensational murder cases.”

But Schell remembers every detail. And he worries about what will happen when Shrader and Barberree are released from prison. “These guys have done this before,” he says, “and they’ll do it again.”

Now Shrader leaves his Charlotte prison to work but must return at night. He is scheduled to be freed on January 12, 1993. Barberree is to be released May 18, 1994.

Both could get out earlier for working while in prison.

Tags

Diane Suchetka

Charlotte Observer (1991)