To Protect and Profit

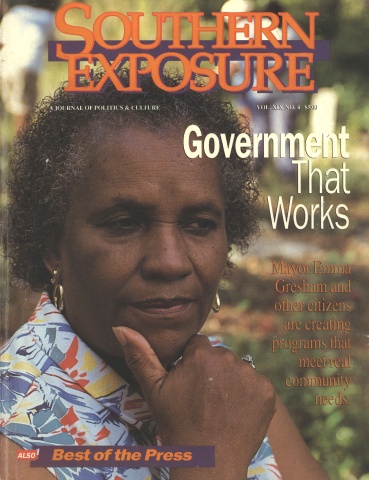

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

This story began with a phone call from an outraged citizen whose car had been seized by Florida police on a trumped-up charge. In the end, the team of Fort Lauderdale reporters who investigated the incident uncovered widespread misuse of police power.

Law enforcement officials are making enormous profits — and questionable expenditures — using a law designed to fight the drug trade. Along the way, innocent victims have been hurt as both enforcement and oversight of the law have been left in the hands of the police, who routinely ignore its nominal guidelines.

Ft. Lauderdale, Fla. — By 1980, drugs had a choke hold on Florida. Cocaine flowed virtually unimpeded from South America, and drug use was rampant. Drug gangs operated with impunity, gunning down competitors and bystanders alike in parking lots, in shopping malls, in broad daylight.

The public, outraged and terrified, had had enough. The federal government demanded action. Police begged for help. The state legislature’s answer was the Florida Contraband Forfeiture Act, which gave police the power to strip drug dealers of money, cars, planes, and boats and to use those resources for law enforcement. The law was designed to hit powerful drug organizations where it would hurt them most.

A decade later, drugs are still a scourge. The kingpins are still in business. But the Forfeiture Act is stronger than ever. The Sun-Sentinel has found that the law has evolved into a money-making venture for cash-strapped police agencies. While Florida police reap enormous profits through the law, the people who most often lose money or property in forfeiture cases are not international drug dealers but small-time crooks — and innocent citizens. The findings:

▼ Police have seized $100.4 million in property and cash since 1987. At least $92 million more was taken before 1987, but no one knows the exact total because police were not required to keep records until 1987.

▼ Many people who lose money or property in seizures are never charged with crimes. Some are clearly innocent. Even so, police routinely keep the seized property, returning it only when the victims pay “storage fees” and other charges or agree to settlements for thousands of dollars.

▼ Police use forfeiture profits to buy high-tech weapons and equipment and to build things such as firing ranges and jails, all touted as free to taxpayers. But some of the purchases later lead to bigger police budgets because they must be maintained and staffed using tax dollars.

During the past decade, police have grown sophisticated in their use of the Forfeiture Act. And as their knowledge has grown, so have profits.

Some say that’s only fair. “This is capitalism,” said Jeff Hochman, legal advisor to the Fort Lauderdale police. “This law lays a lot of golden eggs, and rightly so.” But Hochman, who teaches police how to make money from the act, also cautions them to know the limits of their powers. “Don’t be stupid and kill the goose that lays the golden eggs,” he said.

Of Florida’s top six seizing agencies, five are in Broward, Palm Beach, and Dade counties. Since October 1987, those five agencies have confiscated at least $41.7 million in cash and property. Smaller agencies in three counties picked up at least an additional $19.4 million.

That police use the law to make money hasn’t concerned state legislators or the public enough to reform or even monitor it. “I think [any investigation] would show law enforcement 99 percent of the time is doing exactly the right thing,” said state representative Fred Lippman of Hollywood. Some people might be bludgeoned by the law, but those cases are “anomalies,” he said.

Enough anomalies have cropped up to prompt questions about the fairness and effectiveness of a law that gives police a financial incentive to take away people’s property.

Legal Robbery

David Vinikoor, a former assistant state attorney, lobbied for the law when he led investigations of organized crime in Broward County. “The concept was real simple: It was intended to make it costly to be what we considered a major drug trafficker.” But now, Vinikoor said, “The police are allowed to take people’s property without an arrest. You have no recourse. It’s like blood money.”

Larry Nixon, a Daytona Beach lawyer and former prosecutor, said the law gives police an easy ride. “It allows the government to do great harm with very little investigation. A lot of the process in which the forfeiture law operates deprives people of what we have always considered fundamental rights.”

Most Americans think they are innocent until proven guilty, but that doesn’t apply in Forfeiture Act cases. The law allows police to seize property without proving that the property was involved in any crime. Citizens must prove their innocence to get it back. Moreover, the law contains no penalties to punish police who make wrongful seizures, and it does not require that attorney’s fees or other expenses be paid to innocent victims of the law. That means police have nothing to lose by pressing borderline cases. By doing so, they have steadily expanded the limits of the law.

“It’s legal robbery,” Broward Circuit Judge Stanton Kaplan said. “People have an uphill battle to get their property back. That’s not due process. Due process is when the person taking your property has an uphill battle to keep it.”

Two aspects of the Forfeiture Act are particularly troubling: Neither police nor victims have to appear in court to settle a case, and police don’t have to file criminal charges to seize property.

“As long as we seize property, we know the person’s not going to walk away scot-free,” said Captain Tommy Thompson of the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office. “We’re not just doing it so we can seize the man’s money. We’re doing it because the man broke the law.”

Too often, though, the law hurts people who had no intention of committing crimes. And with forfeiture proceedings heavily weighted against property owners, even the innocent sometimes find it cheaper to settle with police rather than fight in court. In Fort Lauderdale, 92 percent of seizures during the past seven years were settled out of court.

Tom Guilfoyle, head of the Metro-Dade Police Department forfeiture unit, thinks there is too much room for abuse with out-of-court settlements. “It just doesn’t look right,” Guilfoyle said of settlements that are not reviewed by a judge. In Metro-Dade, a judge reviews all settlements. But the law’s other glaring weakness is easy to see in Metro-Dade: only 30 percent of seizure cases are accompanied by criminal charges.

Farmworker Loses $7,000

Antoine Belizaire committed no crime, but the law still made him pay. The Haitian farm worker was stopped for speeding on Interstate 95, and the Volusia County Sheriff’s Department took $17,925 from his car. Belizaire said he was planning to take the money to his family in Haiti. No drugs were found. He was not charged with a crime, but the Sheriff’s Department kept $7,000.

Similar cases were found throughout the state. “Are they really stopping crime or fattening the coffers?” asked Broward Circuit Judge Robert Lance Andrews. “They use [the law] as extortion.”

Paul Steinberg, a former Miami Beach state senator, co-wrote the legislation but said the intent was never to use it against innocent citizens. “When I proposed it, it was supposed to be balanced to get at the wrongdoers’ pocketbooks. [But] I think the government in several specific instances has attempted to seize property when they know the individual is an innocent person,” he said.

Although Steinberg and others say the law needs reforming, no serious legislative attempts have been made to do so. Only two major reforms have come in the past decade. Police now must file a forfeiture case in court within 90 days of the time they seize cash or property, and they must submit quarterly reports to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) detailing forfeiture transactions.

Critics say 90 days is still too long for police to keep property or money belonging to innocent victims. Moreover, the record-keeping reform is flawed. The legislature did not establish penalties for failing to keep and file detailed reports, and it did not give FDLE authority to enforce the requirement.

The result? Few departments submit complete information; others submit no records at all. In some reporting periods, fewer than half of Florida’s 400 police agencies sent in records — even after receiving delinquent notices from the state. That leaves FDLE’s records woefully incomplete, hampering any attempts at oversight.

Other attempts to reform the Forfeiture Act have failed in the face of intense lobbying from police. Fort Lauderdale Police Chief Joe Gerwens, whose department’s forfeiture unit is used as a model by other agencies, said the act has helped “dismantle major criminal organizations and leave them financially devastated.” But Gerwens and other Florida police chiefs and sheriffs concede that most of the criminals are small-time. Gerwens says that sophisticated criminals have learned to shield themselves from the law: Drug kingpins no longer own boats, cars, or homes in their own names.

While the law has evolved into a weapon against small-time crooks and casual drug users, life in Florida may actually be less safe now than it was in 1980. Crimes most often associated with drug use — particularly robbery and car theft — have climbed sharply. In a decade when the state population rose about 35 percent, robberies jumped 50.5 percent and motor-vehicle thefts rose 124 percent. Meanwhile, police powers under the act have expanded. Last year, the legislature gave police the authority to seize houses and real estate.

Critics say reforms are overdue because police have become greedy. “The police — they’re like kids in a candy store,” said Vinikoor, the former Broward prosecutor. And West Palm Beach defense attorney James Eisenberg said, “I see the forfeiture law as being abused and probably the worst law for the purpose of justice that’s ever been enacted. Police appear to be more interested at times with making money and getting forfeitures than in taking drugs off the streets.”

The Toy Chest

For many Florida law enforcement agencies, the Forfeiture Act is the key to the toy chest. They have used it to buy electron microscopes and helicopters and night-vision goggles and portable computers.

Police often spend confiscated money with little oversight. The few guidelines covering Forfeiture Act profits are so vague as to be meaningless. Purchases are limited by little more than a police chief’s or sheriff’s imagination.

“No one really has oversight on the money,” said Rodney Gaddy, a lawyer with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. “The only authority lies in [the law], which says the money needs to be spent for ‘law enforcement purposes.’”

Under the law, county and city governing boards must approve purchases, but it is left to sheriffs and police chiefs to define “law enforcement purposes.”

“They’re the experts. You have to listen to the professionals to get the best advice,” Broward County Commissioner John Hart said. Broward commissioners, with the guidance of the Sheriff’s Office, have approved spending $66.7 million in forfeiture money since 1980 to buy a wide range of equipment, including three helicopters ($2.5 million), an automated fingerprint-identification system ($409,000), and Deputy Wendy, a safety-demonstration robot ($20,500).

Other agencies have been just as imaginative:

▼ North Palm Beach police paid $1,995 for a night-vision scope.

▼ The Volusia County Sheriff’s Department paid $117,000 for an infrared system for nighttime aerial reconnaissance.

▼ Hialeah police paid $67,000 for portable computers.

▼ Greenacres police paid $1,975 for 10 air guns that shoot paint balls.

▼ Coral Gables police paid $34,000 to build a shoot/don’t shoot simulator.

▼ Metro-Dade police paid $430,000 for a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer to identify drugs and a scanning electron microscope to identify gunshot residue and other trace evidence.

Police say effective law enforcement is not cheap. “If we don’t update our equipment, we’re not holding ground with the people we’re combating,” said Joel Cantor, the Hollywood police legal adviser. But even with exotic weaponry, police have done little to stop the well-financed drug cartels the act was designed to hurt. Instead, the weapons and equipment have been used against lesser criminals and in routine law enforcement.

And the fiscal reality is that these high-tech expenditures would never be approved if taxpayers had to foot the bill. “If I had gone to the county commissioners with those requests, they probably would have laughed me out of the room,” Broward Sheriff Nick Navarro said. Local officials might not have laughed, but, said Davie Mayor Kathryn Cox, “We’d have had to cut officers to pay for them.”

Taxpayers Pay

One of the problems with the Forfeiture Act is that it leads to purchases that ultimately cost taxpayers anyway. The law forbids using forfeiture money as “a source of revenue to meet normal operating needs of the law enforcement agency.” But it does not prevent police from buying equipment or building things that later must be maintained or staffed with tax dollars.

One example is the 94-bed, minimum-security jail opened by Fort Lauderdale in 1983. The jail’s construction and first-year operating expenses — about $2.5 million for both — came from forfeitures. Since 1983, taxpayers have paid another $12.6 million for the upkeep and staffing of the jail.

Police sometimes spend the money in areas that have little connection to law enforcement. North Palm Beach police spent $1,095 on weightlifting equipment. The Broward Sheriff’s Office spent $1,240 on emergency lights for Dania City Hall, an emergency hurricane shelter. And Delray Beach police spent $4,000 to install hoops at six churches in hopes that youths would shoot baskets instead of drugs.

Even some supporters say the law needs tightening. They suggest putting forfeiture money into a state fund and then handing it out to local agencies. The advantage? “Oversight,” said state representative Fred Lippman of Hollywood.

However, the lack of direct oversight can be traced directly to the legislature, which in nearly 11 years has never appointed anyone to monitor forfeiture expenditures. And there seems to be little demand for increased oversight, especially from officials at the municipal level, who seem satisfied with overseeing purchases themselves. “Fundamentally, the buck stops with the Town Council. . . . I haven’t seen anything come through that looks crazy,” said Cox, the Davie mayor.

Police defend the way they use forfeiture money. “The state of Florida is suffering a budget shortfall,” said Tampa Police Chief A.C. McLane. “This helps us go into innovative programs.”

Police fiercely protect their right to control forfeiture money and have worked to kill every proposal that would force them to spend the money on drug education and rehabilitation. Senate Majority Leader Peter Weinstein failed each of the three times he tried to get legislation to earmark 25 percent of the money for school resource officers and drug education programs. “The Sheriff’s Association has always opposed it because they want to keep it for their fancy uniforms, SWAT teams, and stuff,” Weinstein said.

Volusia County Sheriff Bob Vogel said Weinstein is missing the point. “I don’t think governmental bureaucrats who can’t find the money someplace else should take it from law enforcement,” he said.

But critics say that some portion of forfeiture money could be freed for drug education, because police do not have to buy all the equipment they need to fight criminals. They use the forfeiture law to seize and keep equipment ranging from airplanes and cars to portable phones and digital pagers. For example, a major with the Tampa Police Department drives a confiscated 1984 Mercedes-Benz 300SD worth $15,000. It’s his assigned police car.

“It was taken from a drug dealer,” police spokesperson Steve Cole said. “That’s one car the city will not have to buy.”

Tags

Mike Billington

The Sun-Sentinel (1991)