Out of the Madness

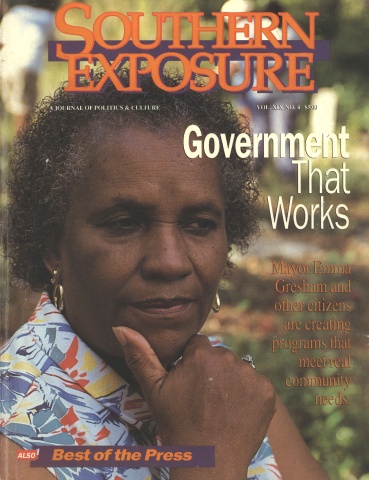

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Jerrold Ladd was a teenager when he decided to write a book about growing up in a West Dallas housing project. During the day he attended classes at a local community college and worked for a while as a clerk in a downtown law firm. But at night he sat up late, remembering and writing.

The result is the very best kind of journalism, the kind that newspapers too seldom publish — an intimate first-person portrayal that illuminates life the way no feature writer or investigative reporter ever can.

Dallas, Texas — I knew the voice coming from the living room did not belong in our house. I peeked around the corner of the stairs and saw two men with guns, one against my mother’s head, one against Fletcher’s head. One of the men looked at me. I dashed past them, running through the back door of our apartment as fast as I could to where my brother and sister were playing. My older sister made me run across the field to get the cops assigned to the fire station. I hoped that since the men had noticed me, maybe they would spare my parents. Many parents had been shot in the head lately.

It was remarkable to me, at the time, how the two officers responded. After being told the situation, they had casual conversations with the fireman on irrelevant subjects. If it had been their parents, would they have felt the same anger I was feeling?

Ten minutes later — it was a one-minute sprint for me — the cops and I arrived at our apartment. There was no blood on the floor, no dead bodies lying around. My parents told the cops everything was OK; they did not turn the men in.

I was no more than 10 years old at the time, and experiences like that were commonplace for me and other children. From as far back as I can remember we had lived in the West Dallas Housing Projects, about 3,000 units squeezed onto a small piece of land. Made of bricks, they looked as if someone took a few old dirty chimneys, molded them together, then cut out windows. In the front and back of each one of them was a small block of dirt. Sometimes there was grass. Most of the units had an upstairs and a downstairs. There wasn’t any carpet on the floor, just hard quarry tile, like an old warehouse bathroom floor. All the walls were white — dirty, old, crusty white. Roaches and rats roamed throughout the night, in your icebox, your closets, your beds. Dead, decaying spiders and their webs were in every corner. We had heat but no air conditioning. On long, hot Texas nights we usually tossed, turned, and sweated for hours unless an occasional cool breeze brought temporary relief. My older brother and I would lie awake sometimes, waiting on that breeze.

The tops of the bridges leading over the Trinity River offered a view of the projects that perhaps revealed their real purpose: Endless rows of them dominated the small area they were in. Later in life, when I had the opportunity to see all of the city, I thought of them as a facility to house the maximum amount of people in the smallest, most underdeveloped side of town. Most of the people were black.

There were only two categories of people — poor but not yet without hope, or a bottomless poor where you had absolutely nothing.

The first category was made up of those who had parents or a parent who worked steady minimum-wage jobs or were on welfare. They sacrificed and allowed their children to dress in fair clothes, have school supplies, and eat hot meals. Caught in the ghetto cycle, being content with day-to-day survival was a way of life.

The latter group was those who had given up — drug addicts, hustlers, burglars and the like. Most of them had kids they didn’t give a damn about. They lived keyed-up on heroin, T’s, and blues. Dope was a defense against the unyielding reality of an inherited future. Most of them had parents who birthed them into these situations, parents already on drugs or from the projects.

I was born into the latter group.

I’ll never forget Pie, a boyfriend of my mother’s. He was probably in his early 30s, heavily built and about 6-foot-1. He moved in and became our father. After he called the first meeting of father and sons and introduced me to personal hygiene, I was so excited. I took a bath with Comet and washed the tub out with soap. He meant vice-versa.

Pie was nice. We had a nice Christmas with real toys that year. I think my mother’s drug addiction made him leave. We could have moved up to the first level with Pie — the one where the parents sacrificed for the kids. Many more Pies would come and go.

At that time, I was a kindergarten student at Jose Navarro. I was six and a fast and able runner. The first escape move I learned was to take off at full speed, wait until the pursuer began to tire, and then let him get close enough to sense a capture. When he reached for me, I would suddenly slide to the ground. He would tumble forward, and I would jump up and run in the other direction. With no real will or endurance to continue, most people usually gave up the chase. When I was a teenager I saw films of African warriors on TV doing the same move. I used that move on a lot of people like the bully Biggun, would-be rapists, kid snatchers, and troublemakers. I ran all the time.

After school, we generally played around the project buildings. There weren’t any playgrounds, not until years later when they built some sort of block wood fixtures with tires hanging from chains — the type you see the monkeys swinging on at the zoos. We wore those swings out, swinging our souls away late into the darkness of the night, if it was one of those nights when our parents were high and didn’t come home.

Sometimes I sat out and watched the drug dealers. From morning until nightfall men mostly in their thirties sat out and pumped drugs into the people. I earned a couple of dollars from them at times by running across the field to a small store and buying cigarettes, sodas, or snacks. There were always at least three or four dope dealers at each corner.

Crippled Jerry was one of the more well-known dealers. His left leg was flawed from birth, and he dragged it when he walked. On several of the corners his workers sold dope. Jerry had money, a lot of money. He bought his 21-year-old girlfriend a new Mercedes-Benz. Some people treated him like some sort of Godfather. Every Christmas he bought all the kids toys and gave all the families hams. If he would not have sold drugs to the families, they could have bought their own hams and Christmas toys.

Gunfights went on all the time. It was normal to see 10 men jump out of cars with pistols and shotguns and come roaming through the projects, looking for their victim. It was both scary and exciting as a kid to see — gas bombs flying inside an apartment, ammunition flying inside a window.

Then there were black parents who rose in the mornings and turned into despaired zombies. They spent their days traveling back and forth to the corner, purchasing a pill or two of heroin and a syringe. They locked themselves in their bathrooms and bedrooms. They tied straps tightly around their arms to make the veins stick out. They sucked a cooked pill out of a bottle top with a needle. With the injection, release eased into their veins, their souls. A few precious moments of freeness were felt.

Perhaps they glimpsed the true inner man. Maybe within this dreamful high they saw the once proud kings and queens of Africa — saw their forefathers, great mathematicians, construct the pyramids. Maybe they felt the courage of a Marcus Garvey deep within them. Somewhere inside there was a man of intelligence and capability trying to get out.

Or did they see the task as so overbearing that they just refused to fight? So they abandoned their pride and families, their manhood and motherhood, their responsibility to their children. And every day was spent hiding the shame of their refusal to resist behind the guile of dope.

“Wake up Jerrold and Junior.” There was no need to wake up. I hadn’t slept for half of the night — was too nervous to sleep. I forced myself out of the bed. A pile of dirty clothes lay just inside the closet. I moved the broken door aside; it had come off its slide track.

Sifting through the pile, I managed an outfit that wasn’t so abhorrent. The shirt was from the early Sixties, the pants dirt-packed.

Somewhere along the way the principles of hygiene that Pie had taught us — bathing at the least — had dissolved. We were probably too young at the time to absorb it — too young to make it second nature.

I left the house and walked to the corner across the street from the graveyard. A few young kids were decent, well-dressed, and from the first group — just slightly more fortunate.

Maybe the bus would have a wreck. Maybe it would forget our street. The big yellow machine rounding the corner spoiled that idea. I was nervous as I boarded, nervous and embarrassed.

Hampton Road led us to a long bridge over a deep valley of grass, shrubbery, and scarce trees. Across the bridge, Hampton turned into Inwood Road. As we descended on the other end, a remarkable change took place.

I had heard rumors of the place we now headed toward. Yet no foresight could have prepared me, or any of the children, for what lay ahead. We were being bused to the heart of the white neighborhood.

I noticed that the buildings were all pleasant and new. There were a lot of pretty cars. We drove farther. Houses started appearing unlike any I had ever seen. They were nice, new, and clean. As we drove on, they grew larger and larger.

We came around a curve. I saw the biggest house. You could have placed half of a project block on its front yard alone. It resembled a castle, and had a long, twisted road leading up to its front door, then circling back out the other side. Who could have lived in that place? It contrasted with anything that I had ever been exposed to.

The standard of white American life emitted itself along the way. Those same white kids who I would encounter later probably had risen to the scent of new clothes, fresh school supplies, and a hot breakfast. Their parents probably had made them brush their teeth and comb their hair.

Thus the odds began from birth.

School was unpleasant. I often daydreamed. We were some of the filthiest kids. The school bus driver, Mr. Holley, was also our P.E. teacher. He called me into his office one day and made me show him my once-white but now brown socks. He did the same with my underwear. He encouraged me to wash my clothes by hand and to bathe myself — we had forgotten what Pie had taught us.

I made friends with a few white kids. I’ll never forget Dean Hurst. He was mature and sincere for his age. He sometimes gave me money for my lunch when I was too ashamed to use the free-lunch ticket. They made the free-lunch kids go through one line; the paying students went through another. One line was all black, the other all white. It was very humiliating.

Fletcher and my mother had been together for about a year. Fletcher was also addicted to heroin. He was a quiet, conservative man and not very smart. Tall and light complexioned, he appeared to be in his late thirties. I remember when he first introduced me to fishing. He took me down to the pond with two rods and reels and a bucket of worms he had dug up from his mother’s back yard. Beyond the cattails he cast the lines into the water. He propped them up in the air using a Y stick and twisted the reel until the lines were tight.

We sat for a few minutes. I was told to watch the movement of the tip of the rod, which would signal a fish nibbling the bait. I paid no attention. Then I heard Fletcher say, “There he goes.” I turned around in time to see the tip of the rod bend almost to the water. As suddenly as it had tightened, the line slackened. “There are carps in this lake as long as a man’s leg,” Fletcher informed me. I went on to catch fish that enormous, some so big we had to go into the water and drag them out by their gills.

My mom enjoyed fishing also. She used the activity to combat her drug habit, though it never worked. I’d bait her hook then throw the line far out into the deep, where she liked it. As long as I would bait and cast the line, she would sit there and haul in the fish. Those fish filled our tummies many nights.

Every few months there was a different man, as a father, in our lives. You can imagine how confusing this was for us as children. The minute you adapted to the new person, out the door he went, and in came another. Every new man my mother had we called Daddy. That’s how bad we longed for a father figure.

I cannot recall one strong male role model in my youth. This was pervasive in every family. Most of the women were husbandless, all the children fatherless. Where was the strong, black, soothing hand in the moments of our uncertainty? Where was his wisdom and guidance to lead us around snares and guide us through tribulations? Where was my father who resists despair and holds high his torch of hope?

The longest my mother stayed with one was about a year, and he was Fletcher. She and Fletcher had started selling drugs for Crippled Jerry’s brother, Fred. Fletcher shot up a lot of the dope and fled to California with the proceeds from the rest. That hurt my mother. I remember how she stayed restless and upset after his departure.

Then there were the men who were just basic tricks. It was so embarrassing for all the other children to know your mother was selling herself. She was ashamed of herself, too, yet could not resist the hold of her habit.

If our mom was in a bad mood, it was best to stay clear of her. Kids were a means to release frustration, and loud shouting and cursing accompanied it. Every kid I knew received whoopings. Sometimes, up and down the streets, the kids yelled and screamed, “OK, Momma, I won’t do it no mo.” Some of them received whoopings in their front yards or the middle of the street. As I had, some children were made to take whoopings with extension cords, standing naked and wet. It borderlined on torture.

Although my mom put us through hell, I love her, we all love her. I remember the day I came home and found the house empty. Everything was gone, sold for little or nothing to support her drug habit. I sat on the porch meditating that night, calm and undaunted. I thought deeply, focusing on all the efforts she had given at overcoming her habit, at all the drug rehabilitation hospitals and halfway houses she had visited. I remember how she had wept over her failed attempts. She wasn’t to blame. She tried but just wasn’t strong enough to defeat the impossible.

No, I did not blame her for being born into the faithless latter group and turning to the substance that helped her bear the burden of the tremendous odds against her. She never had a chance. At the age of 14 her mother made her quit school and help take care of her seven brothers and sisters — clean, cook, and wash. And when she was 20, she moved into her first project apartment with three kids. It was her mother who gave her heroin as a remedy for a headache. Her own mother handed down the tradition of the latter group. “Here, take this and fail like the rest of us. You’ll never defeat these impossible odds anyway.”

Late evening sunlight reflected from an eerie, empty project unit. The windowpanes were all broken. Glass and debris were scattered around. I peered out our front door and down the street trying to locate the voice coming through the microphone. It was full of energy and shouted strange words. Excitement was about. Who was causing the excitement? I walked to the corner to find out.

In the front yard of someone’s apartment, right there on the dirt, a small group of men and women had gathered. Their faces appeared stern, dry, and serious. All of the women had on dresses or skirts and the men had on suits and neckties. They were black.

They had small, round objects with cymbals attached and patted them against their outstretched hands. Others repeatedly clapped or patted their foot to the rhythm. A lady with stubby limbs held the microphone and sang, “Watcha gonna do, whatcha gonna do when the world’s on fire.” After she finished, an old set-faced man stepped forward and began to talk. “The Lord can bring a change in your lives, if you’re hungry and worried, if you have bills to pay, if you’re on drugs, whatever the problem, the Lord can make a change,” he told us.

I felt hurt and wanted this God to help me and my family. When he asked did anyone want to try Jesus, through the laughter of some of the spectators, I stepped forward. Nervous and ashamed, I was led off by a woman. She told me to ask the Lord to save me. I said, “Lord, save me.” She shouted in my ear, “Save me Lord.” I said, “Save me Lord.” “Ask the Lord to save you.” “Save me Lord.” “Now thank him.” “Thank you Lord.” By this time, she was hyped and spitting in my ear. I heard moaning and eerie, ghost sounds coming from around me. I opened my eyes and saw one lady bent forward with her arms outstretched, screaming.

The intensity slowly let up. I was asked my name and told that I was now clean and saved. I now needed to come to the church to learn and grow. The arrangements were made. I went back home, telling no one about my secret.

I soon learned how to pray, all about sin, living holy, the end of the world, and the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. God loved me and did not want to see me suffering, hungry, and depraved. Without hesitation, I trusted God. I started going to the church every time they had service, maybe five times a week. Word soon spread around our block that Jerrold was Saved.

I began joining in the shouting and testifying. Allowing the mood of the atmosphere to take me, my feet stomped and my voice wailed. I became well-trained in the Scriptures. I was happy to know that I could have a good, normal life — never hungry, always happy.

I only had to die before I received it.

After a few months of this, I prepared for my biggest challenge. I turned my faith toward our house. God was going to take my mother off of drugs. I knew he would do it, I possessed no doubt.

That evening I went into her room and opened the drawer where she kept her needles. I threw them in the trash. When she came home and found out, she slapped me around and turned over furniture. I told her that God loved us and wanted to help us. Since she was from a holy family, my words disturbed her. She went into her room and shut the door. I was determined. I sat at the top of the stairs in front of her door. I stayed there all night so that she would not go out.

Around three o’clock, she emerged from the room, then took a seat beside me. I told her that we could do better; she agreed. I told her how God was making me happy and that he wanted to do the same thing for her. After our talk, we decided that our whole family would go to church the next Sunday.

That Sunday, my mother, sister, brother, and I went to church. When the pastor asked who wanted to be saved, they all went to the altar. They each went through the process and my mother wailed like a seasoned pro. I recall feeling ashamed as my mother went through wild, uncontrollable yelping and screaming.

After we arrived home that evening I noticed a worried look in my mother’s eyes. As strong as her desire was, she was still helpless. No matter how hard she tried, her peace of mind came only from the heroin pills.

I kept going to the church for a while. I began to notice things more in depth. I saw how most of the members never lasted long and were always worried, deprived, and depressed. The way the religion was arranged, it didn’t answer key questions. I noticed how everyone felt naturally disturbed when the sermon hinted around the color of Jesus and the origins of the religion. Their knowledge of the religion was limited, and they could never answer the question: Was it truly ours?

Among the gossiping, boredom, grief, and home-threatening problems, my church activities diminished. One day, I simply left, never to return.

I was around 13 then and becoming restless about improving our family standard. It had gotten to a point where on days that we ate, it was only a small serving of red beans and maybe some corn bread. Sometimes we only ate mayonnaise sandwiches, ketchup sandwiches, mustard sandwiches, or just plain bread. That was all.

Hanging out on the corner one day, this man told me how I could get my family something to eat. He knew some foreigners who lived on the other side of the projects and had a lot of money. He told me that he was going to take their belongings. He would give me a cut if I would help carry the merchandise to his car. I said OK, never giving it a second thought. He was a dope fiend and desperate for a fix. I was desperate for everything.

Shortly after, we arrived at the back door of this apartment. I was nervous, yet the thought of a lot of money kept me involved. He busted the glass pane above the lock and unlocked the door. We both crept inside. A big color TV was against a wall. We lifted simultaneously and carried it to his car.

After another quick trip we were at a dope trap. I helped him unload the TV and carry it into the apartment. That was when I heard this woman say she was going to whoop my ass. I turned around and saw my mother seated on a couch. The man I was with told her he had just asked me to help him carry the TV. He explained that I knew nothing. He gave me $5, telling me he would have to find change for the $50 bill — to give me my other cut. My mother told him she would go along and bring back my change. She called it making sure that I would not be messed around, but I knew that I’d never see the rest of the money.

After that, I learned how to shoplift for food. On days when our hunger wouldn’t let us rest, my brother and I stole things that were easy to conceal — cans of sardines, small packages of rice. A bowl of rice and a tall glass of water did justice to our indiscriminate hunger.

Another hustle we learned was to go to the shopping center late Saturday nights. The newspaper companies dumped hundreds of papers on the sidewalk to be delivered the next morning. A couple of us would arrive around one a.m. and sift through the piles, picking out all of the TV guides. Back in the projects we would go from door to door selling our magazines for a quarter apiece.

In those days, my mother made us do everything. Sometimes I thought we were slaves. If she wanted a glass of water we brought it to her room. If she wanted her cigarette lit from the stove or her neck massaged, we did it. She sent us to Ms. Dee’s house to buy her pain pills for $1.50 each. If Ms. Dee was out, we were told to walk miles to other places.

To this day I dislike anyone who pops as many pills as my mother. She took maybe five or six Anacins a day and sniffed Afrin nasal spray. She was as addicted to them as she was to heroin. If she was out of either one, even if it was three o’clock in the morning, we had to walk almost a mile to the shopping center to buy them. If there was no way to buy them, we were told to steal them. The cool words “Do it for Momma” and “That’s Momma’s baby boy” did me in every time. Kindness was so rare.

Bring Momma’s house shoes, go and borrow some sugar for Momma, and it was best not to object or you would receive one of those horrible beatings or get slapped across the head. One time, before one of her blows landed on my face, I darted out the back door while calling her a bitch. I climbed a tree, staying until I thought the action had died away.

The mailman delivered the notice that we had 30 days to vacate our project unit. I was 14 and it was autumn 1984. During those 30 days, my mother stayed depressed. We had no money, so there was nothing we could do. We were going to be homeless.

“Jerrold,” she screamed. “Yes ma’am,” I responded while hurrying up the stairs. I was called into the bathroom where she sat on the toilet. There was a stocking tied around her arm. She gradually brought the needle up toward her arm. She said, “Jerrold, I’m too nervous to hit myself. I’ll put the needle in place and then let you hold it. All that you will have to do is squeeze it.” I was in a trance — I quietly came in the bathroom and shut the door behind me. She placed my hand on the needle with her nervous, shaking hand and said, “Do it for Momma.” A little kid, I understood her torment, her complete dependence. I held her shaking arm still, while slowly squeezing the clear liquid into her. I did it for Momma.

Tags

Jerrold Ladd

Dallas Morning News (1991)