The Nuclear Forest

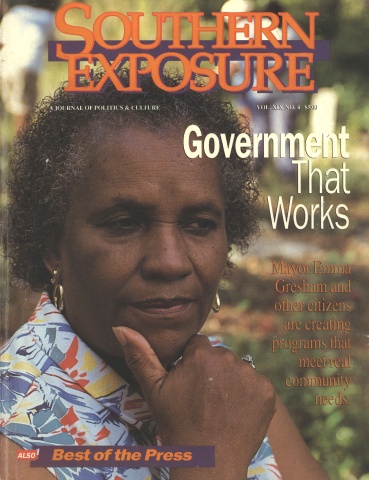

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Through relentless digging and paper chasing, reporter Karen Kirkpatrick produced an in-depth look at the dangers to hunters and residents around the former Georgia Nuclear Laboratories near Dawsonville, Georgia — an abandoned, unguarded lab that should have been cleaned up two decades ago.

The lab once operated an unshielded nuclear reactor known as “the monster” that was supposed to help design and test an atomic-powered warplane. But the A-plane project turned into a billion-dollar boondoggle, and the reactor was used to irradiate an entire forest to simulate the effects of a nuclear attack.

Today the forest around the lab remains radioactive. But thanks to Kirkpatrick, the state has strengthened security measures and ordered an independent taskforce to investigate continued health risks.

Dawsonville, Ga. — Radioactive debris from a nuclear laboratory dismantled more than two decades ago continues to endanger people frequenting parts of the Dawson Forest recreation park. One spot is so polluted that its radiation level easily exceeds current safety limits set for nuclear plants operating in the United States, state records show.

A state health department report in 1972 said the forest — once home to the Georgia Nuclear Laboratories — had been decontaminated by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation employees and contractors, and therefore was safe for public use of any kind.

But four years later, the state Environmental Protection Division (EPD) returned to the forest some 20 miles west of Gainesville and found that five areas were contaminated with radioactivity. Two spots were so polluted that state officials ordered them placed off limits to the public by enclosing the areas with four-foot-high hogwire fences topped with barbed wire.

Signs warning of danger were also posted, but residents and state officials tell of repeated trespassing at the forest’s two most radioactive sites. Both fenced areas have repeatedly fallen prey to vandals and the elements. Some community leaders and nuclear scientists say permanent steps are needed to rid the forest of radioactive debris — and the unseen danger it poses to the public.

A three-month investigation by The Times has revealed that:

▼ Radiation from one site exceeds accepted levels at licensed nuclear facilities. Radioactive wastes have been found in the soil and vegetation. Even very small amounts of cobalt-60 — once manufactured at the forest — pose the risk of cancer, health and nuclear-industry experts say.

▼ The EPD concedes that some of the remaining debris is so “hot” — or radioactive — that it can’t be removed without spreading it, endangering both workers and the environment. The price tag of a cleanup would be in the millions, said the state’s top nuclear watchdog, James Setser of the EPD.

▼ The highly radioactive areas were open to the public for nearly five years before a 1976 state inspection identified the hazardous remains. The security fences posted around the two most dangerous sites in 1977 have holes big enough for a person to fit through.

After talking with The Times, the EPD notified the Georgia Forestry Commission to replace the fence around the hot-cell building — where irradiated materials were tested and examined — and to repair the fence at the cooling-off area — where those materials were kept in an open environment after they were irradiated.

State officials say they plan no additional action at the former reactor test site, other than maintaining existing security measures. John Braden, a spokesperson for the property’s landlord — the city of Atlanta — also says he’s satisfied with the status quo.

A Thorny Problem

Shortly after the city acquired the property from Lockheed in 1972, Atlanta officials ordered workers to block entrances to the only remaining above-ground structure — the hot-cell building — and to remove surrounding topsoil to reduce potential radiation exposure. Crews also buried entrances to a maze of underground tunnels, said Braden, marketing director for the Department of Aviation, which oversees the site for the city.

But those safeguards have not worked, admits Braden, who said that visitors hack away at the hot-cell building and continually break through tunnels and fences. “We’ve even planted roses hoping the thorns would keep them out,” Braden said. The city always knew there was radioactivity at the site, but state officials assured Atlanta the levels met standards. “There is an acceptable level of radiation,” he said.

As for the state, environmental officials acknowledge the existing and past problems at the site, especially the radioactive waste left after decontamination efforts in 1972.

“There’s no way I can defend what went on there,” said Setser, chief of the EPD program coordination branch and chair of the state Environmental Radiation Advisory Committee. “I would just as soon not have this problem. We’ve spent a lot of money monitoring that site,” he said, estimating the cost at about $250,000 since the EPD came on the scene in 1976.

“There is no question two areas are still contaminated,” Setser said. “I firmly believe the only radioactivity we’re going to find is confined to those areas.”

That doesn’t satisfy Forsyth County Commissioner Barry Hillgartner, who has expressed concern that he and others may have been exposed to radiation when they explored the site as teenagers in the 1970s. He wants the site cleaned up to remove any risk of exposure to present and future generations.

But what action, if any, will be taken remains unknown at this point, nearly two decades after the state of Georgia declared the site radiation-free.

The Monster

Once envisioned as a $100 million state-of-the-art defense complex in 1956, the Georgia Nuclear Laboratories was a joint venture between the U.S. Air Force and Lockheed to create a supersonic atomic jet. The remains of that vision are what some people call a radioactive graveyard.

The complex’s labyrinth of tunnels and concrete structures was designed as a test site for what ended as a billion-dollar government boondoggle — the so-called “atomic war plane,” a Cold War nuclear aircraft that was never built. The complex was designed to test aircraft components that could withstand enormous amounts of heat and radioactivity.

The facility, initially called “Air Force Plant No. 67,” had been scaled down to a $15 million version when it opened in 1958. After the official demise of the A-plane project in 1961, the laboratories were used for other radioactive experiments and for the manufacture of radioactive substances.

The site included above-and below-ground structures, two reactors, and an on-site railroad to transport irradiated material from the big, unshielded “Radiation Effects Reactor” across the Etowah River to the cooling-off-area and back across another bridge to the hot-cell building. Neither the rail cars nor the irradiated materials were covered during these journeys. In the hot-cell building, workers in the adjoining “Radiation Effects Facility” examined the radioactive cargo by remote control.

The unshielded reactor — lab employees called it “the monster” — normally rested in a pool of water. When fired up, it rose above ground to send radioactive waves and particles into the test materials — and the environment. The reactor sat inside an aluminum building, similar to a warehouse.

Located 750 feet from the Etowah River, the monster generated 10 megawatts of power capable of irradiating large quantities of materials in a natural environment — including the forest, according to Lockheed and other records. Compared to large commercial reactors used today, such as Georgia Power’s 1,100-megawatt Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, “the monster” would appear tame, but the Dawson reactor was used in a different way. All its power was directed freely into test items and the environment.

Nuclear Aftermath

The monster reached self-sustaining atomic chain reactions in 1958. It ceased operation July 16, 1970, as Lockheed ran out of contracts for its unique service.

Two years later, the city of Atlanta, scouting land for a possible new airport, hooked up with Lockheed and paid the defense giant $5.1 million for the 16-square-mile site. A stipulation in the contract required that the land be fit for public use by the contract’s expiration date, June 23, 1972.

To meet that deadline, Lockheed and its contractors spent months digging up and shipping out tons of contaminated earth and other materials to radioactive waste disposal sites, including the military’s Savannah River Plant in South Carolina and the Oak Ridge Nuclear Laboratory in Tennessee.

The huge concrete lab and the office complex next to the hot-cell building were destroyed by Lockheed — for undisclosed reasons — before the company sold the site. At least part of the lab building had once been contaminated — and then cleaned up — following a 1967 accident when fans in the pressurized hot-cell building reversed, drawing radioactive particles into the lab, said former lab health physicist Mark Ham.

The hot-cell building, which had been built to test the effects of radiation exposure on materials, was used in later years to manufacture large quantities of radioactive substances for industrial and university use. It proved too hot and too solid to tear down, former employees said, and still looms over the site.

The reactor itself was dismantled and transferred to its final resting place at the Savannah River Plant in 1971. But even after it was shut down, according to Lockheed files obtained from the EPD, the reactor was still pumping out radiation levels up to 500 rems per hour — a dose that could swiftly kill a human.

Water from the Etowah River routinely had been used to cool the reactor, Lockheed reports show. The resulting liquid waste was demineralized and then dumped into an on-site seepage pit near the reactor. Another pit was used to contain radioactive waste from activities at the hot-cell building.

During the 1972 cleanup, the liquid wastes remaining in the 100,000-gallon pits were sucked out and shipped to an undisclosed nuclear waste area, according to former lab administrator Don Westbrook. A second reactor — in use for just a few years — was much smaller and was removed as waste material in 1971, Lockheed reports show.

On June 22,1972, the state health department ruled that the area now known as the Dawson Forest was fit for any use. The next day, it became the property of Atlanta. One month later, a memo issued by the state health department said, “This department and Lockheed, both with moral and legal obligations to the public, have agreed to remain liable for any decontamination that may be called for in the future at the site.”

Officials at Lockheed headquarters in Marietta refused detailed comment on the lab site. Director of Communications Dick Martin was given a list of questions, as well as a summary of what The Times had discovered. In a prepared statement, the company said it sold the site to the city of Atlanta nearly 20 years ago and is therefore no longer responsible for additional cleanup or other action.

The 1976 Report

After Atlanta purchased the property, the public had free access to the site, and in 1975, the city made an agreement with the Georgia Forestry Commission to manage the land. But in 1976, a representative of the Natural Resources Defense Council — an environmental group — began asking questions about the former lab site.

That same year, the state Environmental Protection Division inherited radiation monitoring duties from the health department, and began an exhaustive survey of the site. The EPD uncovered five hazardous areas:

▼ The ground surrounding the spot where the large reactor was based.

▼ The hot-cell building where irradiated material was tested and manufactured, as well as the surrounding land.

▼ The outdoor cooling-off area, including several acres across the Etowah River where high-level wastes were temporarily stored, low-level wastes were permanently buried, and irradiated materials were taken until they decayed to lower levels.

▼ The reactor seepage pit where waste waters from the reactor were stored.

▼ The hot-cell seepage pit where other liquid wastes were stored.

In its report, the state survey team informed EPD program coordinator James Setser and then-division director J. Leonard Ledbetter that it had found hot particles distributed in the soil with radiation levels up to 850 millirems a year at the reactor seepage pit. Levels of up to 2,278 millirems a year were found at the hot-cell seepage pit. At the cooling-off area, one spot measured 8,760 millirems per year. The current federal standard for acceptable radiation levels at nuclear power plants is 100 millirems per year.

The probable dose of radiation that most people receive from the environment each year is about 100 millirems, experts say. With an added dose of 100 millirems, “it’s unlikely you’d see any discernible health effects. You couldn’t measure it,” said Bill Cline, chief of nuclear material safety at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission office in Atlanta. But the NRC and other nuclear agencies agree that any additional dose above environmental radiation should be avoided because of possible health risks.

There is not yet an agreement on where the line is drawn. Some say even the lowest doses — including those received from the environment — can cause cancer over a period of time; others maintain there is probably a threshold level that humans can withstand, said Ken Clark of the NRC regional office in Atlanta.

Fences and Signs

Because of the high readings at the hot-cell building and the cooling-off area, the EPD recommended installing the four-foot-high hogwire fencing topped with barbed wire. On the fences, they advised posting standard “no trespassing” and “hazardous area” warning signs. The Georgia Forestry Commission poured dirt into tunnel openings and around the hot-cell building, according to the EPD recommendations. Workers also stashed the radioactive hot-cell slabs that forest visitors had used as picnic tables back inside the building and boarded it up.

EPD officials felt the other three areas of contamination fell within regulatory guidelines for public access and were not dangerous enough to warrant concern — even though the 1976 report shows the two seepage pit areas to have levels above 500 millirems per year. “I disagree there were levels that exceeded standards,” EPD official James Setser said recently. Following the fencing and posting of signs, EPD officials — including Setser — went on to tell area residents that no danger existed.

The decision to fence in two areas to keep the public away from the highest levels of radioactivity was made by Setser, DNR Commissioner Joe Tanner, and EPD Director Leonard Ledbetter. “I made the recommendation the site be closed,” Setser said. “I don’t remember the details of how the discussion went. The final consensus was that a four-foot hogwire fence with two strands of barbed wire would be a sufficient deterrent.”

But that hasn’t been the case, said Winston West of the Georgia Forestry Commission. The fences are constantly vandalized. “They fight their way through the barbs,” West said. Former lab administrator Don Westbrook said that someone had once used dynamite to blast a way into the hot-cell building.

“Gross Failure”

The state’s security efforts, explanations, and testing procedures don’t satisfy Ivan White, a scientist and nuclear expert with the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurement. The Maryland-based group sets state and industry radiation standards and decommissioning guidelines for nuclear facilities. Chartered by Congress, the group issued the standards the EPD used when it surveyed the lab site in 1976.

After learning from The Times of the 1976 state report detailing remaining contamination and of the subsequent reports issued by the EPD, White said, “No wonder industry has such a black eye. They’re going to have to decontaminate that whole thing. They need to go in there and remove that stuff and put it in a radioactive waste disposal area.”

White said that according to standard techniques used in cleaning up nuclear facilities, the radioactive materials never should have been left on a site where the public risks exposure. Warning signs and fences are not enough to protect the public.

“I wouldn’t walk around in there,” he said. “You don’t know what’s in there until you really evaluate it and they didn’t do an adequate job of evaluating it. The least they could have done was concrete it over.”

Instead, the 10,000-acre forest has become a prime hunting and horseback riding spot and attracts year-round outdoors enthusiasts. The former lab occupied three areas of at least several acres each in the center of the forest. Residents say that portions of the forest where the laboratory and reactor sites once stood are frequented by area families, hikers, and others who eat and drink near the radiation sources.

Yet camping and eating near the contamination are the worst things people can do, White said. Both pose the risk of ingesting or breathing airborne radioactive particles. “Today when we look at these situations, one of the first things we look at is how likely we are to have human intrusion,” White said. Anything fenced or locked or unguarded is considered an invitation to some people, he added.

“This is a mess as far as I am concerned,” White said. “A gross failure of the state of Georgia.”

Tags

Karen Kirkpatrick

Gainesville Times (1991)