This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

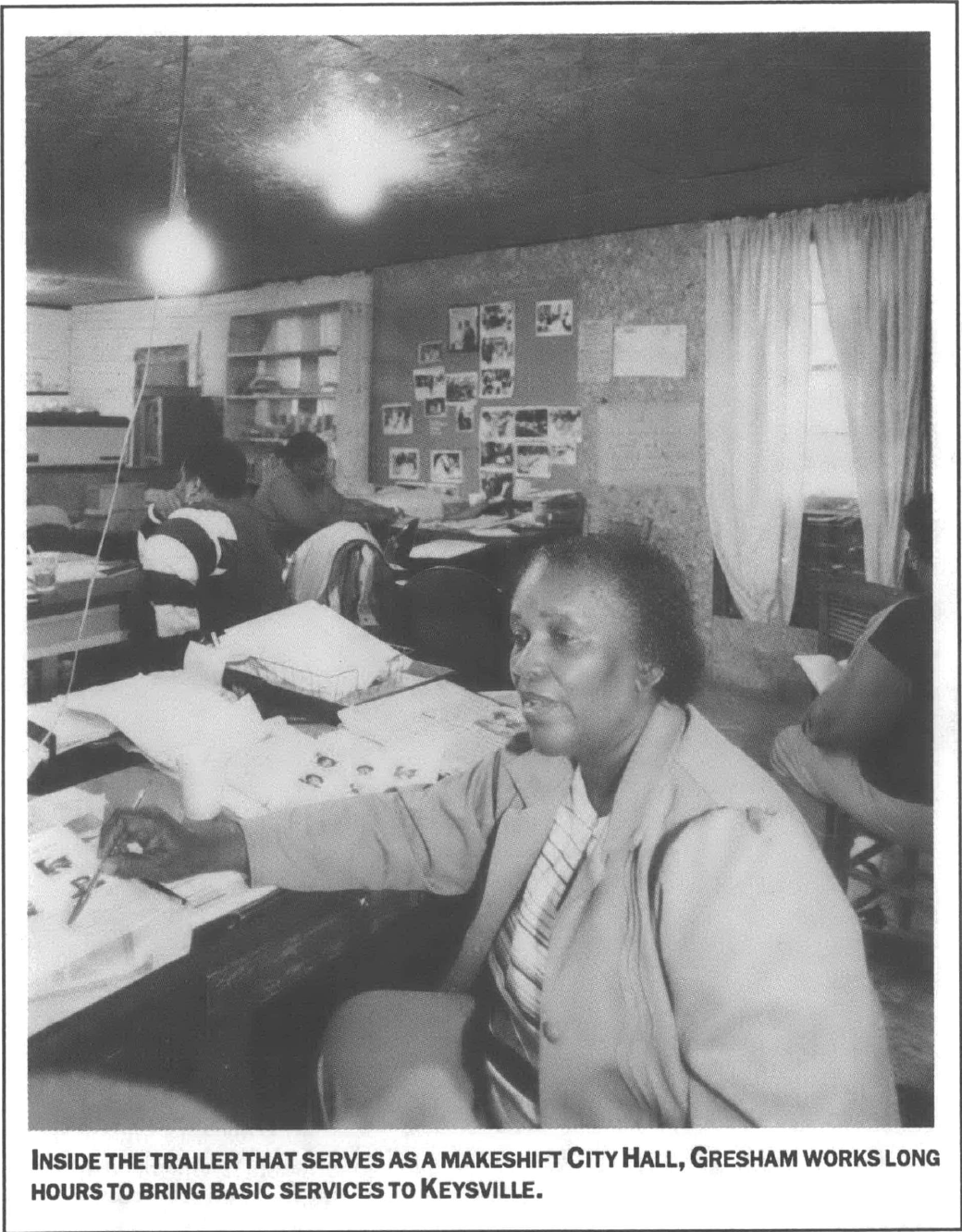

Keysville, Ga. — One steamy afternoon last July, Mayor Emma Gresham entered the double-wide trailer that serves as City Hall in this small town near the South Carolina border. She passed the photograph of herself with former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young and was walking toward her office when her assistant intercepted her with the good news: Keysville had just won a $400,000 federal grant to provide indoor plumbing to local residents.

A chorus of drawn-out “ohhhhs” filled the trailer — then laughter and applause. “This is great news,” the mayor beamed. “Keysville has had water problems for a long time.” As her staff celebrated, Gresham entered her spartan office, sat behind her desk, and began calling council members.

For most small Georgia towns, getting a water grant would hardly qualify as a remarkable event. Indeed, at first glance there’s nothing at all remarkable about Keysville. A traveler passing through this east Georgia hamlet on an average day would probably think nothing of the youngsters planting flowers in front of City Hall, or the dozen or so street lights scattered throughout the town, or the three red fire trucks parked in front of the volunteer fire department.

But Keysville is no ordinary town. Just five years ago, it wasn’t a town at all, its local government having been disbanded by whites during the Great Depression. With no local leadership or city services, it had slowly become a desolate place, where weeds and dirt roads bespoke its character. Its population had dwindled to 380 souls, three quarters of them black.

But in 1985, black residents pulled together to resurrect their community. They assembled a municipal government that has worked relentlessly to restore Keysville as a viable and self-sufficient city — a struggle that received an important boost from the federal grant to build the town’s first water and sewer system.

Emerging from her office that July afternoon to rejoin the celebration, Mayor Gresham stood beside a poster of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and other historic black leaders. To many of the Keysville residents around her, Gresham seemed to belong among those shining black heroes in the picture — a living symbol of their town’s dramatic rebirth.

The Quarters

At 66, “Mama” Gresham looks like the retired schoolteacher she is — her graying hair and stern features softened by her grandmotherly way with kids. The youngest of seven children, Gresham remembers the big camp meetings that used to be held every summer in Keysville under the pavilion that still stands near the new post office. “I was a little girl, running down there to see the people play the guitar and sing,” she recalls.

As Gresham and older residents tell it, the days were much better back then. Nestled in the midst of rich timber and farm land, the town had its own elementary school and a big two-story building with an auditorium where operas and plays were performed. Both were built by a philanthropic organization called the Rosenwald Foundation. “We had a lot of stores, a school, a planer mill and a sawmill and a railroad depot,” Everett Poole, a retired grocery store owner, told the Atlanta Constitution.

Henry Key, the oldest resident in town and a descendent of its namesake, used to haul red Georgia clay to harden the sandy streets. “I don’t recollect how much they paid me, but ’round then, if you made a dollar a day you were making gracious plenty for yourself,” Key told a reporter.

But then as now, the town was sharply divided along racial lines. Keysville was named after Joshua Key, a white man who took his black cook for a mistress. Most of his descendants and other white residents lived along the main highway, while most blacks occupied a neighborhood known as “the Quarters” on a small hill above the road. Although black citizens comprised a majority of Keysville, they were not permitted to vote. Whites controlled the economic and political life of the entire town, holding every municipal office and owning virtually every business.

The Great Depression changed all that. Younger residents began to move away in search of jobs; stores began to close; older white leaders died off and no one came forward to replace them. Eventually, white residents gave up on local government. The town held its last election in 1933, the year Emma Gresham turned eight.

“It just happened like an old house going down,” Everett Poole recalled. “There wasn’t no sudden break in it. It just slowly dropped into the ground.”

Disbanding the town government had little effect on white residents like Poole. Most continued to make a decent living, and today their modest ranch-style houses include indoor toilets, running water, and satellite dishes.

But for the black majority, things went from bad to worse. With few local jobs to support them, many found themselves living in broken-down trailers and drinking contaminated water from rain barrels. Zelma Walker lived in her family home — until the floors and roof almost caved in.

Many black residents like Walker were forced to rely on outhouses and outdoor water pumps. There were no street lights, no police, and no fire protection. The nearest fire department was 20 miles away. According to state figures, the average Keysville resident still earns only $4,335 a year.

The Charter

Emma Gresham witnessed the slow and painful deterioration of her hometown. She attended Paine College and Atlanta University, and left to teach school in neighboring Augusta. But she kept her residence in Keysville, spending her weekends back home so she could attend church with her family.

When Gresham decided to lay down her chalk over five years ago — after more than 30 years of teaching — she could have enjoyed a well-earned rest. Instead, she found herself thrust into the middle of a political whirlwind over the future of the town.

Gresham took the lead in a self-help organization of black residents called Keysville Concerned Citizens who were struggling to improve living conditions. For nearly two decades, the church-based group had been selling chicken dinners to raise money for community improvements — a modest endeavor that Gresham never expected would lead to the mayor’s office.

“I owe my political ambitions to my faith in God and my desire for all people to be treated justly,” says Gresham. “I had no idea I’d ever want to be elected to any office. I’m really not a politician, but I know what this town needs.”

The biggest need was for water and sewers. In its 101-year history, Keysville has never had a water system — which Gresham says underscores the importance of democratic government.

“Towns all around here have water and sewer systems,” Gresham says. “Burke County communities with as little as 75 residents have one. This says to me that if you do not have anyone to represent you governmentally, you can’t get things you need as a community.”

Keysville Concerned Citizens did their homework, and learned that federal and state funds were available for providing water and sewers. Hoping to apply for aid, the group met with prominent whites to find out whether the city had ever been incorporated. But white residents, who already enjoyed indoor toilets and running water, brushed the Concerned Citizens off.

William and Jean Harmon, owners of Keysville Convalescent and Nursing Center — the largest employer in town — told the group that they had recently installed a water system and were not interested in supporting a town government. They also told the Concerned Citizens that the town had never been incorporated.

The matter was forgotten. But not for long.

One day, a woman who owned a small grocery store asked the Burke County commission for a permit to sell beer and wine. The commission turned her away, saying she would have to ask the town of Keysville for a license. Herman Lodge, a black commissioner, had found a copy of the town’s 1890 charter at the courthouse. The charter, it turns out, had never been officially invalidated.

But asking the town for a liquor license was an impossible task. More than half a century had passed since Thomas Radford was sworn in as the last mayor of Keysville. He and every other city official were dead.

The woman who applied for the beer permit has since moved away, her name forgotten. But her simple request revealed that the town of Keysville still existed on paper, giving residents the tool they needed to revive their long-dormant government.

The Vote

Encouraged by Herman Lodge, Keysville Concerned Citizens began to push for local elections. In 1985, six black residents ran for office unopposed, and were sworn in as the new mayor and town council of Keysville.

But white residents, fearing that the new government would levy taxes to pay for city services, went to court to keep blacks from resurrecting the town. Five hours after the new city officials were sworn in, a Burke County judge barred them from taking office, ruling that the elections were invalid because no clear boundaries existed for the town.

Black residents asked an appeals court to strike down the injunction. They asked the General Assembly to designate city limits. They asked then-Governor Joe Frank Harris to appoint interim officials. All their requests were denied.

When new elections were held in 1988, black residents were prepared. They handed out leaflets and held town meetings and worked with the American Civil Liberties Union and Christic Institute South, a social justice group based in North Carolina. Nearly 200 residents went to the polls, electing Emma Gresham mayor by a 10-vote margin and giving black candidates four of the five seats on the town council.

Civil rights leaders hailed the election as an important victory in the struggle for racial equality in the rural South. “Civil rights did not touch all of America, particularly rural towns,” Georgia state representative Tyrone Brooks said after the vote. “It is time for us to direct our energies not on the Atlantas and Chicagos and New Yorks, but on small towns like Keysville.”

But white residents continued to fight the new government, saying the voting boundaries included too many blacks. Nursing home owners William and Jean Harmon even filed suit against the town to block collection of a new business licensing fee — an assessment that threatened to cost the couple $62.50.

Finally, after another year of legal wrangling, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the boundary dispute, clearing the way for Keysville to hold another election in 1989. This time, Gresham beat white opponent J. Upton Cochran by 59 votes, and blacks won all five council seats.

“I feel that God blessed us,” says Gresham. “That last election made us official and we’re able to continue making Keysville a better city.”

Gresham says she wasn’t surprised by the white opposition. “I saw the challenges as part of a group of people who are afraid of change, who had never seen anything like this before,” she says.

White residents insist their primary conflict with blacks is one of economics. Even with federal and state grants to build a water and sewer system, many white homeowners worry they’ll be stuck with large tax bills to operate the system once the grants run out.

“We’ve got just a few households where both parties are working,” nursing home owner Jean Harmon told the Atlanta Constitution. “Most of the others are widows living on fixed incomes. If they come in here and slap a bunch of city taxes on them, they won’t be able to live here anymore.”

J. Upton Cochran, who was defeated by Gresham in the mayoral election, agrees. “Our economic interests are just different from most of the blacks,” he says.

But one white resident says such opposition is based on race, not economics. “The whites never did want black people to have anything,” says 67-year-old Elsie Munn, who went to work for Mayor Gresham as a part-time librarian once she saw how the new government was helping residents. “They — blacks — have always been pushed around, stomped on, and cussed by some white people. I think the white people should join in and help.”

The Work

Under the leadership of Mayor Gresham, the new municipal government set to work immediately to do what it could to help. Funded primarily by donations from black churches across the nation, officials moved quickly to make real, physical changes in the community: adding street lights, creating a fire department, opening a post office, and staffing a day-care center.

But local businesses are still boarded up, and some homes are without indoor plumbing. “I’m not going to be satisfied until every citizen of Keysville has running water and there are clean streets, livable homes, a larger city park, more definite police protection, standard garbage pickup, a real library, a school, and other basic services,” vows Gresham.

The town presently has a small park with a basketball court, a softball field, and a swing-and-slide gym set. The library is a small room added to the City Hall trailer and stocked with an odd assortment of donated books. Garbage collection is handled by Quinten Gresham, the mayor’s husband and president of Concerned Citizens, who is paid $25 a week to pick up trash and take it to the dump. And for police protection, a Burke County deputy drives through town once a day and stops at City Hall.

Residents know that making Keysville self-sufficient is going to take hard work. Gresham often puts in 12-hour days, but she is not alone. Council members, who work for free, are busy keeping the community informed and finding ways to raise money for basic services.

What’s more, the new government has energized the people of Keysville, imbuing them with the spirit of improving their own community. “I’ll continue to take my truck and pick up our trash until we can get a sanitation department,” says Quinten Gresham. “Until we can get the proper aid, we gotta do for ourselves.”

Residents are also taking part in Visions of Literacy, a new program that helps townspeople learn to read. Gresham, appointed by the governor to the Georgia Council on Adult Literacy, estimates that half of Keysville’s residents need the program.

“We have residents who are outstanding citizens, who really are strong in their commitments to community, but they have not had a high-school or formal education,” Gresham says. “In order to encourage economic development, you have to have people who are trained and educated. This is why we started this program.”

Five instructors — including the mayor — teach an average of a dozen students, who range in age from 19 to 51. Kathie Johnson, a former teacher in the Richmond County school system, says she doesn’t mind driving 30 miles from Augusta to Keysville in return for a small travel stipend. “The students are motivated and cooperative,” she says. “Whatever they’re asked to do, they do it. It’s a refreshing difference from working with eighth-graders all day.”

The literacy program has made a dramatic difference for Keysville residents like Georgene Allen, a 42-year-old cook at nearby Fort Gordon and a soldier in the Georgia National Guard. Allen wants to go to nursing school, so she attends literacy classes to brush up on her English, literature, social studies, and math.

“You should have seen us when we first started,” she says. “I started from ground zero. You aren’t associated with school every day like the kids are. It gets hectic. I have to study, and if you don’t do it regularly, you get rusty.”

The Money

But perhaps the greatest success of the new government came in July, when the town received the $400,000 federal grant to pump water to the homes of its residents. “The grant will give Keysville the greatest thing it has ever had: a water system free of contamination,” the mayor says.

Much of the credit for qualifying for the grant belongs to Margaret White, an administrative assistant to the mayor. White was sent to Keysville by Virginia Water Projects, a non-profit organization based in Roanoke that helps communities obtain safe drinking water.

White — at 66 the same age as Gresham — had also recently retired. But duty called, and she began traveling to Keysville for one week each month.

“I felt that I didn’t need to sit down any longer,” White says. “I had read about Keysville and their troubles, and since I had gone through a similar situation in Virginia, I knew I could help them. Why should someone have to keep reinventing the wheel?”

White went to work to acquire federal and state grants for the town. A former employee of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, she was familiar with the ins and outs of the federal bureaucracy. She knew where to look, what papers to fill out, whom to talk to, and when deadlines needed to be met.

White helped Keysville secure an emergency grant in 1988 that gave many residents their first taste of clean drinking water. Now, the $400,000 grant will enable the town to pump water directly into their homes.

“Hard work pays off,” says White. “In the end, I think Keysville will be the kind of city in rural America that it was when Mayor Gresham was growing up here. Water and sewerage is as good as here, and I eventually see a small school coming back. I see a Headstart program and an increase of industry that provides jobs for the residents here so that they don’t have to travel to Augusta and Waynesboro.”

The Future

Gresham shares those goals. Because Keysville lacks services that other communities consider necessities, she says, most young people are still forced to leave town to find work. “Keysville cannot attract industry in the condition it’s in now,” she says.

State and federal officials have been impressed by how much the Keysville government has accomplished. “These people are not ignorant,” Jacqueline Byers, state manager of city and county governments, told The Washington Post shortly before the 1989 elections. “They don’t know the workings of local government, but as fast as they’ve caught on to everything — from talking to state government department heads about grants to marching on the Capitol — they’re brilliant. All you have to do is point them in the right direction and voom, they’re gone.”

Although the new government has made significant progress in reviving the town, it still faces hostility from white residents. “It has caused some bad feelings, especially with the older citizens,” nursing home owner Jean Harmon told a reporter. “I just wish it could really quiet down.”

But J. Upton Cochran, who lost to Gresham in the mayoral race, believes the controversy will not abate as long as blacks control the town. “Blacks have always cried when there were all white governments, but it’s the same thing down here,” he says. “We white residents have no representation.”

Despite such opposition to majority rule, Gresham remains optimistic about the future of Keysville — and about relations between the races. “What I want most of all is for the white people and the black people who live in this town to sit down and talk,” she says. “If we can sit down and talk, I think whites will understand why this is something that needs to be done. The future of our kids is at stake. Our very destiny is at stake. These things are worth paying taxes for, taxes which are not going to be much anyway.”

“I believe Keysville will once again be the town I always loved,” she adds. “I always told people Keysville was an exceptional town where black and white lived together peacefully. I want to see black and white working together like they did when I was a little girl. It was a unique town.”

Gresham looks around her tiny office in the makeshift trailer that serves as City Hall. “Keysville will become more than a crossroad or a stop sign,” she says. “It will become a model of hope for other small towns that have been locked out, shut out and left behind.”

Tags

Frederick D. Robinson

Fredrick D. Robinson is an Atlanta freelance writer. (1991)