“Gotta Be Bold”

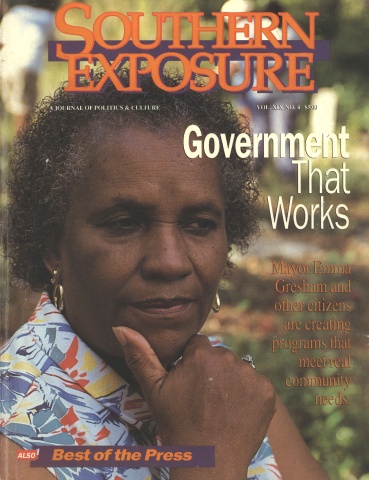

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

As a young pediatrician working in the Mississippi Delta in the 1960s, Aaron Shirley discovered that a comprehensive medical clinic could really make a difference in the health of a region.

Shirley was working two days a week at the Mound Bayou health center, a government-funded project set up by Tufts University in the nation’s oldest black community. The clinic provided both preventive and curative services, and it also ran a farm cooperative. The results were astounding: Within four years, the community’s infant mortality rate was cut by more than half.

That inspired Shirley to help found the Jackson-Hinds Comprehensive Health Center in 1970. Operating clinics in Jackson and rural Hinds County, the federally funded center takes a broad view of health — a view that encompasses everything from decent housing to clean water.

Statistics show that the comprehensive approach works. According to Lisbeth Schorr of Harvard University, Jackson-Hinds immunizes children and screens them for anemia at a much higher rate than in similar communities. And since the center began operating clinics in the local schools, the dropout rate for school-age mothers has fallen from 50 percent to 9 percent.

At a time when numerous cutbacks are plaguing our health care system, Shirley has found ways to keep those services flowing. He spoke with Delia Smith about the founding of the center and some of the services it offers.

Being a doctor was not my idea. It was planted in my mind by my sisters, one of whom was a nurse. As far back as I can remember, she told me I was going to be a doctor. My preference was engineering. But at that time, scholarships were available for doctors. They weren’t available for engineers.

I got my training in pediatrics at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. I was their first black resident. This was 1965, in the midst of the civil rights turmoil. And I finished my residency and set up private practice in Jackson. At about that time, Tufts Medical School was establishing a center in the Delta as a demonstration project. I got involved in that by going up there two days a week to work as a pediatrician.

Going to the Delta was how we conceived of the idea for the Jackson-Hinds Comprehensive Health Center. The center was established in 1970 at Cades Chapel Church in Jackson and in an old renovated bus in rural Hinds County.

Let me tell you why we founded the center: We had so many patients that could not afford private doctors. Those that did not have health insurance had to go to the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Almost everything was segregated.

We told our patients who couldn’t afford us, “OK, you pay us later.” But if they needed prescriptions, they couldn’t get them. If they needed to go to the hospital, they couldn’t get in. It was frustrating for us to do all we could, but then the patients needed more, and they didn’t have the money.

It was extremely hard to obtain funding for the health center. First of all, we had to prepare grant applications, something we had never done before. Our grant application was eventually approved by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity, but the governor vetoed the grant. We had to put forth a lot of justification to show that the governor was wrong in his veto. It was difficult to get the head of the OEO to override the veto.

Poor health doesn’t occur in a vacuum, especially among low-income individuals and families. Often the medical problems that we see are related to environment, the home, the neighborhood, so we try to look at whatever might contribute to the poor health of individuals.

We have a rural clinic that serves a lot of elderly individuals. Several years ago, many of our patients who were being treated for chronic conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and arthritis were making very frequent visits — beyond what we expected. Eventually we learned that they were coming to the clinic more to be in other people’s company than to see the doctors. We implemented a noontime feeding program and provided transportation and brought them in. They ate the meal and they socialized. Believe it or not, the diabetes and the hypertension were under better control, and there were fewer complaints about aching joints.

Another example: Twenty-five to 30 percent of our patients don’t have running water. In the summer months, the water they have comes from the runoff from the roof when it rains. We notice an unusual number of cases of diarrhea in the summer months, especially in infants who were being bottle fed. We checked the water that the formula was being mixed with, and noticed that the water was being contaminated with coliform bacteria. This is what prompted us to deliver water from a tank truck to those families. Then we teach them, when they use the runoff, to boil the water to make it safe.

We do a lot of work in the schools. I used to do sports physicals, along with some other doctors. Kids had to have a doctor’s statement saying that it was OK for them to participate in sports. We volunteered to do this, because these kids didn’t have private doctors.

We were finding that a lot of those kids had problems that they didn’t know they had. They had ear infections. Some had high blood pressure. They had gone untreated, and things had led to more serious problems. So we became concerned that if the athletes had these problems, then the general school body probably had problems too. But they weren’t coming into our clinic.

So we began to establish clinics in the Jackson area schools. We have them in four high schools, three junior high schools, and one elementary school.

Students can’t just come to our school clinics and say, “I want this and I want that.” They have to enroll. They have a physical and complete history and a psychosocial assessment, in which they tell us what’s happening in their lives. From that assessment, we determine their risks for pregnancy, depression, disease, violence. If, after that, the students want contraceptive services, we provide them. But they can’t just come in and seek out contraception, without having participated in the overall program.

It hasn’t cut down on sexual activity. It has cut down on pregnancies among the students who use the clinic.

We’ve had some students who found out they were pregnant by coming in. We’ve had others who found out they were pregnant and came in to start prenatal care. Some were scared to death. We had a pregnant sixth-grader this year, and another sixth-grader about three years ago. They don’t know what is happening to them. They don’t have any idea what the implications are. If we weren’t there, I fear that they would just be lost.

The boys have problems too. They have problems with their parents, with their peers, with gang members, with feeling isolated, no male figures. They see one of us, and we show them attention, and they keep coming back just for the male-figure attention that they don’t get at home. They’re longing for somebody.

From a medical standpoint, the center has made good, first-quality health care available to a lot of people who otherwise would not receive it. We have dentists, we have optometrists, and we do our own X-rays in our lab. So a lot of people are getting early preventive care before it gets to where they need a kidney transplant or they have a stroke.

The other major achievement is our link with the community. We do the work, but we have a governing board that is made up of community people. So we have given the community a sense of ownership and a sense of pride. At least 51 percent of the governing board members must be active patients. They volunteer; they don’t get paid. I think it’s their way of contributing.

How do we stay effective in a time of cutbacks? Gotta be willing. Gotta be innovative. Gotta believe in it. Gotta be bold. You have to constantly come up with new ideas. We keep abreast of what’s about to happen. If we realize that a cut is coming, then we start thinking up ways that we can take up the slack.

You see, we’re funded at about 65 percent of what it takes to operate. We have to generate 35 percent. So we have to find ways to broaden the base of our patients. That means we have to adjust our hours for working people. We’ve got to constantly counsel our staff about how to treat people. We’ve got to operate like a business.

I think the center will thrive. I think it will thrive because the notion has caught on and the need is so great. The doctors in private practice cannot afford to treat people on a private-fee scale. So we are getting more and more patients who are being encouraged to come to us rather than to be a burden on the non-subsidized doctors. As the need expands, we’ll find innovative ways to serve them.

Tags

Delia Smith

Delia Smith is a teacher assistant with the Jackson Public Schools. (1991)