The Forgotten River

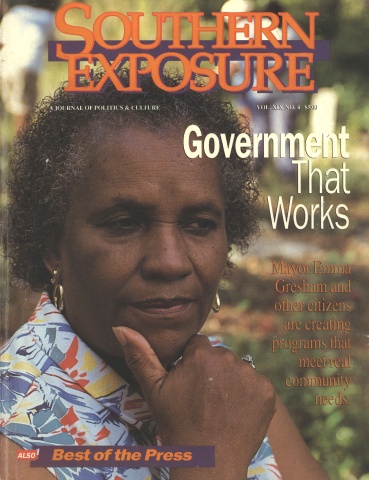

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

The Fenholloway River is where Procter & Gamble dumps treated chemical waste from making cellulose, a key ingredient in such modern conveniences as rayon and disposable diapers. The costs? Mutant fish, dead seagrasses in the Gulf of Mexico, unknown health risks, and the loss of the river itself.

For 37 years, the people of Perry, Florida remained silent about the pollution. They got used to the smell and stopped fishing in the river. Then, in the fall of 1990, reporter Julie Hauserman stumbled on the Fenholloway while looking for a river to canoe for an environmental feature.

The series caused bitter divisions in Taylor County between “pro-P&G” and “pro-environment” factions. And it created a public relations dilemma for the company, which has been pursuing a ‘‘green” marketing strategy.

Perry, Florida — In northern Taylor County, where the Fenholloway bubbles to life, the river is a magical place, a liquid ribbon graced by fern-studded banks and fluted cypress trunks.

The beauty is short lived. A few miles downstream, the ferns and clear waters are gone. The sprawling Procter & Gamble Cellulose mill dumps 50 million gallons of wastewater into the beleaguered stream each day, with the state of Florida’s blessing. “As far as water quality, I can’t think of anything worse in Florida,” said Jim Harrison, an Environmental Protection Agency scientist in Atlanta.

The river, which runs through Perry 50 miles southeast of Tallahassee, is the only Florida waterway classified as “industrial.” In a system that rates the quality of water bodies from 1 to 5, the Fenholloway is the only 5. It has the lowest standards in Florida.

Regulators say P&G’s water-treatment system is as good as any in the state. The company, which has won praise from environmentalists over the years for conserving vast tracts of Florida wilderness, has spent millions on pollution controls. Still, the Fenholloway is a small, 35-mile-long river, and P&G officials say the huge amount of water that comes from the plant can’t help but have an impact.

But one thing makes the effect worse: Because the plant sits on Florida’s only class 5 river, P&G can legally pollute more than any other mill. P&G has fought to keep that industrial label.

P&G officials say they have no choice. Other Florida mills sit on larger rivers, where pollution is diluted, but the mill’s waste makes up nearly the entire flow of the Fenholloway for much of the year. There’s no technology, they say, to make the plant’s undiluted waste cleaner than industrial standards. It is the price we pay to turn pine trees into sheets of cellulose that will one day return as disposable diapers, coffee filters, and rayon clothing.

There are other, more ominous costs.

Government officials warn people not to eat Fenholloway fish because the fish contain dioxin, a possible human carcinogen. And EPA scientists who took samples in 1989 found some spots in the river where absolutely nothing was alive. People living along the river have pollutants in their water wells so chemically complex that the state can’t say what they are, much less say for certain whether the water is safe to drink.

“There are things in that well water and things in that river water that we haven’t seen in Florida groundwater anywhere,” said Tom Atkeson, an epidemiologist with the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services.

All this pollution dumps straight into the Gulf of Mexico, as far as two miles out, killing seagrasses that would normally act as a marine nursery ground. At the government’s urging, P&G tested oysters and fish where the river meets the gulf and found no detectable levels of dioxin, but no one has tested crabs, although a Swedish government study indicates that crabs absorb dioxin more than fish do. People who catch blue crabs near the river’s mouth say the crabs sometimes turn dark from the plant’s waste.

The Perry mill is both the economic lifeblood of Taylor County and the executioner of the Fenholloway, Florida’s forgotten river. “There’s no bones about it. They [P&G] have a license to kill,” said Mark Thompson, a scientist with the Florida Marine Fisheries Commission. “That license is the state’s class 5 designation.”

“Bearded Lady” Fish

Thirty-seven years after the mill opened, no one swims here. The Fenholloway is home to mutant fish and not much else. Will Davis, an EPA scientist in Gulf Breeze, found female fish in the Fenholloway that are developing male characteristics. He calls them “bearded ladies.”

Davis said the phenomenon has been reported in just two other places: downstream from the Champion paper mill near Pensacola and downstream from a pharmaceutical plant in Italy. “The Fenholloway is the most drastic example we’ve seen in Florida of these types of hormonal effects,” Davis said. “We think the microbial breakdown of the pine oils at the mill is the source of this.”

The EPA also ranked the plant among America’s top five for dioxin risk. Three years ago, when the EPA tested the plant wastewater, the agency found dioxin levels 1,900 times higher than it considers an acceptable background risk, said Marshall Hyatt of the EPA’s Atlanta office.

P&G spokesperson Dan Simmons said the EPA is using “old data.” Simmons said P&G has spent $40 million to reduce dioxin, an unwanted byproduct of the bleaching process. New equipment, he said, will cut dioxin emissions by 50 percent or more. And he points out that the dioxin levels found in Fenholloway fish are well within limits set by the Food and Drug Administration. Under federal law, you can buy fish at the market that have more dioxin than the ones found in the Fenholloway, Simmons said.

Even though many people who live near the mill say the river has improved since the 1970s, the 22-mile stretch between the plant and the gulf is still the color of too-strong coffee, and it still stains everything in it. According to a 1989 EPA report, “The devastation to the river is also transferred to the estuarine reach. Where seagrasses should flourish, excessive staining of the water column has precluded adequate light.”

Other Florida rivers have advocates, but there is no “Friends of the Fenholloway.” Few environmental groups have watched over the mill. Surprisingly few people have pestered the state to find out what is wrong with the drinking water. Along the Fenholloway, there is only Perry, a company town where the state’s most polluted river is considered the reasonable price of progress.

Lowering the Standards

To entice P&G to Taylor County, an act of the 1947 Florida Legislature designated the rural county as a “manufacturing and industrial area.” The county could “deposit sewage, industrial, and chemical wastes and effluents, or any of them, into the waters of the Fenholloway River and the waters of the Gulf of Mexico.” P&G bought the Perry plant in 1951 and produced its first pulp three years later.

Today, state regulators say their hands are tied because of the 1947 law and the industrial label. But records show that the Department of Environmental Regulation actually lowered the water-quality standards for the Fenholloway as recently as 1986.

The DER rewrote the rules to allow the plant to dump water with what scientists say is an appallingly low oxygen content. During some of the year, when the Fenholloway is low, P&G can dump water with only .1 milligrams of oxygen per liter of water. A healthy water body has 50 times that much oxygen.

Can fish live in water with so little oxygen? “Not unless it’s a type of fish that could gulp air at the surface,” said Rick McCann, a Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission biologist.

Like other mills, the P&G plant must monitor itself, then submit the data for state and federal review. According to P&G figures, the plant has had no significant water-quality violations since 1988. P&G officials are proud of that record, and say it proves they run a top-quality shop.

Company officials also make no bones about the fact that when people in Taylor County complained about polluted wells, P&G provided bottled water and drilled new wells, free of charge, even though company spokesperson Simmons says no studies have tied the plant to the pollution. “The bottom line was, people were concerned about their water,” Simmons said. “Our response at the time was to take action first and ask questions later.”

Everyone agrees that the P&G operation meets state and federal regulations. But both the federal EPA and the state Department of Environmental Regulation are plagued by high turnover and tight budgets. That contributes to regulatory gaps:

▼ Sinkholes have opened beneath two ponds where P&G wastewater is treated before it flows into the Fenholloway, raising the possibility of groundwater contamination. The DER knows about the sinkholes, which appeared in 1988. But a series of calls to the EPA turned up no one at the agency who knew the details about the sinkholes.

▼ The plant produces what one state scientist calls “an almost infinite variety of compounds,” but the state requires P&G to track only eight groundwater pollutants. The wells near the treatment ponds don’t monitor dioxin, although the EPA has found dioxin in P&G wastewater.

▼ P&G dumps the sludge from its manufacturing process — which contains dioxin and other chemicals — into huge, unlined pits on the plant property. Although Florida is making all counties install expensive liners to keep landfills from leaking, some industry waste pits, like those at P&G, aren’t required to have liners.

▼ The woman who is writing P&G’s federal discharge permit for the EPA said she didn’t know about the drinking-water problems along the river, the sinkholes, or the unlined sludge pits. She also hadn’t heard about the dead seagrasses at the river’s mouth and the “bearded lady” fish found in the river, even though both studies came from her own agency.

▼ The plant’s federal discharge permit expired in 1989, but since the EPA hasn’t written the new permit yet, P&G is allowed to operate under its seven-year-old permit.

▼ Every few years, the EPA requires the state and P&G to prove that the Fenholloway can’t be improved. In 1987, the agency said Florida didn’t have enough scientific evidence to say the river had to keep its industrial label and gave the state 90 days to either change the classification or prove its case.

Florida sent in another report — but in the four years since then, the EPA has done nothing. “It has dragged on longer than is easy to defend,” admitted Phil Vorsatz, chief of the EPA section overseeing water quality in the Southeast.

Black Muck

Believe it or not, there is a fish camp on the Fenholloway, two miles from the gulf. It’s a tumble-down place on a dirt road through swamp and cabbage palms. Linda Rowland, who runs the camp, caters to people who want to fish in the gulf.

Rowland knows the P&G plant: She worked there 14 years before a disability landed her at the fish camp. She doesn’t know much about government regulations, but she knows what she sees: too-black water and thick clots of foam down the river some days.

At first glance, the Fenholloway near the fish camp looks like North Florida’s other blackwater streams, with arching branches, ethereal Spanish moss, and cabbage palms crowded tightly along its banks. It looks fine until you get close enough to see its hard, glassy surface, close enough to see how the inky waters snuff out life.

Rowland points to black muck at the river’s edge. “See this? It looks like mud, but it’s not. It’s chemicals,” she says. There is a metallic, chemical smell coming off the Fenholloway, and with it, the ripe odor of the mill.

Although she’s spent her life along this river, Rowland is surprised to hear that the Fenholloway is Florida’s only industrial river. She wonders why no one works to clean it up. “We had four sets of environmental men here. We never hear back from them. I told them, ‘Why do you come down here and do these tests and get so mad and then do nothing?’ What’s the use of all these pollution controls if they don’t do what they are supposed to do?”

Grantham McMillan is a salty crabber with a face as weathered as the dungaree overalls he’s wearing. He pulls into the fish camp with a load of blue crabs. “When they dump, you see foam down the river, and it chases the crabs off in the gulf for two or three days,” he says. “They done took tests and all for days out here. They said how bad it was and didn’t do nothing about it.”

Rowland has crab traps in the gulf, too. She climbs into a boat and sets out to check her catch. As the boat putters from the fish camp toward the gulf, the engine churns up water that is opaque and sewer-brown. The Fenholloway widens near its mouth, and the forested banks give way to vast, pale marshes.

“My granddaddy was an Indian, from right around here,” she says, scanning the choppy ocean waters for her crab traps. A few miles out, she finds one and hauls it up. “Whenever they are dumping, your crabs and your bait will be real dark looking,” she says. This time, the crabs look healthy.

“They say they are not hurting the people, but they are. They are taking our wildlife away, and they are taking our fish away. The bad thing about it is, you live right here on this river, and you think, ‘Boy, I could be Fishing today.’ But you can’t.

“Some of our catfish have got big sores on them. There ain’t no way I’d eat them, but some people do. . . . My cousin caught some bass in the river once. He put them in a frying pan, and you couldn’t even stand it, it smelled so bad. We put it out, and the dogs wouldn’t touch it.”

She sighs.

“They’ll always have to dump it. But when they dump it, it should be clean. They can do it. Other paper mills can do it.”

As she turns the boat back for the short trip up the Fenholloway, Rowland appraises the marsh and the way the river narrows into the forested corridor, where no houses mar its banks. “Just look at it, and think how pretty it is,” she says. “Look how pretty it is. And how polluted.”

The Company Town

Until recently, few people in Perry were willing to speak up about the pollution. This is a company town in a rural county with the highest unemployment rate in Florida.

P&G put Perry on the map. It pays half the property taxes. It has a payroll of $40 million and contributes “several tens of millions” more to the local economy each year, said company spokesperson Dan Simmons. About 1,000 people work at the plant, and another 1,000 work in related industries.

Over the years, people in Perry have been reluctant to say much about the mill’s pollution for fear it would cost them their jobs. Andrew Wood, a Taylor County commissioner for the past six years, said simply, “We would be in a terrible fix without them.”

But Wood believes Taylor County can have both a clean river and industry. “They’ve improved the river,” he said. “When they first came here, everybody called it the Stink River. It was so bad you had to hold your nose when you went over the bridge.

“Then again, the people that worked out there said it smelled like money to them. I reckon it depends on where your paycheck comes from.”

Now that so many wells have gone bad, now that the government has told people not to eat Fenholloway fish because of the cancer risk, people are speaking up. Some worry that their benefactor may be poisoning them.

Gwen Faulkner has a weekend place along the Fenholloway. Last year, the water started to smell funny. It had an oily film. “When you dry yourself off, you can’t really dry off,” she said. “P&G says the pollution’s not coming from them, and of course they are going to say that. They are the livelihood of this community. Yes, they have done good for the community. Does that justify what they have done to the environment?

“Once the environment is gone, they can afford to pick up and move and leave us with nothing. If we don’t have our environment and our drinking water, what else have we got?

“I want to live in Perry. I just want to be healthy.”

Tags

Julie Hauserman

Tallahassee Democrat (1991)