This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Hope, Ark. — Driving down the main street of this small Southern town, it would be easy to mistake it for a movie set from the 1960s. Unlike many rural communities, Hope has remained relatively unchanged over the years. Downtown shops — everything from a taxidermist to a soda fountain — have managed to survive despite competition from a nearby WalMart. Every phone number in town begins with a 777 prefix, and residents simply recite the last four digits when exchanging numbers.

Perhaps the biggest change in Hope took place in 1968, the year the town integrated its schools. But even then, it didn’t take widespread protests to bring children of different races together in the same classroom. There were no sullen mobs toting ax handles, no federal troops, no New York Times reporters. The well-funded white educational system simply agreed to meld with the town’s collection of grossly neglected black schools, and the voluntary merger went off without a hitch.

The relative calm didn’t surprise residents of Hope, a small community in the farmlands of southwest Arkansas. After all, the series of events that culminated with integrated schools unfolded the same way most things did in Hope — slowly and quietly.

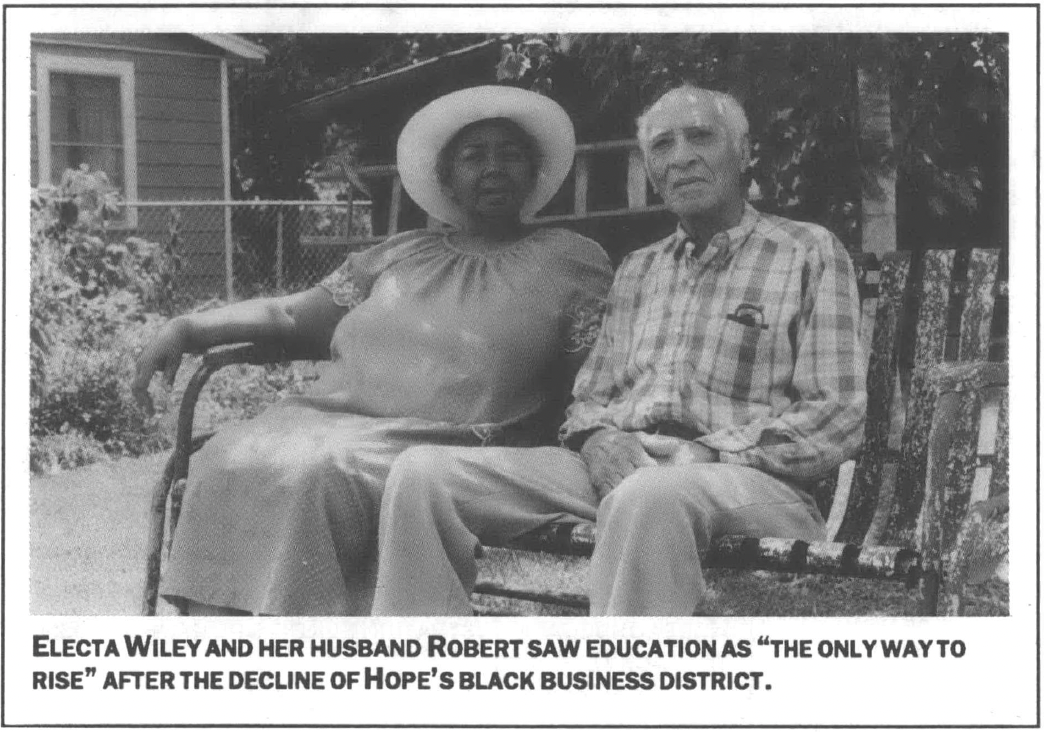

“I think whites in Hope have always thought they didn’t want a stink,” says Electa Wiley, a retired black educator who grew up in Hope. “They didn’t want to give the town a bad name.”

But while Hope held on to its good name, its “integrated” schools also retained the underlying inequality that had defined the segregated system. Black students, confined largely to low-level courses and shut out of most extracurricular activities, continued to receive an inferior education. Black teachers and administrators watched their numbers and influence dwindle. The school board, in charge of hiring and planning, was dominated by whites, who were assured of control by at-large elections that diluted black votes.

“It had come to the point where blacks were no longer included in determining the direction of school policy,” recalls Rosie Davis, a black teacher who was passed over twice for a job as principal. “We had a board that didn’t represent the whole community . . . and we had people getting promotions who didn’t deserve them.”

Determined to fight for the equal education that had been promised by integration, black residents decided to break with the tradition of quiet change in Hope. In 1988, a group of black parents, students, and teachers filed a class-action lawsuit against the Hope School District. They accused the school board of widespread discrimination in the hiring and promotion of blacks, and they challenged the at-large election system on the grounds that it effectively blocked participation by minorities.

The suit, which was settled out of court a year later, has already had a profound impact on education in Hope. The eight-member school board now has four black members, and the school district has its first black principal in nearly a decade. But perhaps most important, both blacks and whites have come to view the school system as their own.

“I think a lot of tension has disappeared,” says Charles Morris, a newly elected white school board member with two children in the Hope system. “Before the suit, all the board members came from one side of town, and it just wasn’t fair.”

“It’s a better situation for students now because they feel they have someone to listen to them,” agrees Rosie Davis. “All students have a chance to live up to their potential now.”

First Day of School

Davis, an elementary school teacher who grew up in Hope, began to realize that something was wrong almost as soon as white and black schools merged. Integration broke up a tight-knit community of black teachers and sprinkled them throughout the new district.

“Human relations workshops were set up for the teachers and it was a smooth transition,” Davis says. “But the outspoken ones were separated so there was the least resistance to anything negative about the change.”

Communication wasn’t the only thing lacking in the new system. The grades and test scores of black students began to plummet, along with their membership in the National Honor Society. College preparatory and honors classes soon came to be dominated by white students, while blacks were increasingly relegated to remedial and vocational courses.

“Somehow the aggressiveness for learning you saw at the old black schools was quenched,” Davis says. “It just disappeared.”

The influence of black teachers and administrators was also vanishing. Although blacks comprised more than 40 percent of the 10,000 residents of Hope, they accounted for just 22 percent of city teachers by 1988. Only one black had ever managed to make it on the school board — first by appointment, and then by running unopposed for re-election. Aside from the high-school basketball coach, no blacks led athletic teams or directed after-school activities. And while there had been three black principals in the old system, the integrated system employed only two blacks on its 14-member administrative staff — both vice principals.

After integration, Davis had managed to become principal of Hopewell Elementary, but the board closed the school in 1981. She took a position as a reading specialist at Yerger Middle School — once the pride of the all-black system — and was publicly promised an administrative post during a board meeting.

Years passed, but the promotion never came. When she was passed over twice by white candidates lacking her qualifications, Davis filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. When she was passed over a third time, she called a former grade-school classmate — Little Rock civil rights attorney John Walker.

Homecoming

Walker was the obvious person to call. A native of Hope and a graduate of Yale Law School, he had built a reputation as one of the foremost civil rights attorneys in the nation. Known as “Too-Thin Johnny” during his school days in Hope, he went on to fight desegregation cases for black parents in Little Rock and other school districts throughout the state. His intimidating style served him well in the courtroom, earning him as many enemies as friends in the legal community.

“He’s using the Voting Rights Act as a club,” an unnamed lawyer complained to the Arkansas Times. “He goes into these situations where he knows the city government can’t afford to litigate, and when he’s through, whether he is right or not, the makeup of the government will be different.”

Although he moved to Houston after the tenth grade, Walker has no trouble remembering the iniquities of the old segregated school system in Hope. The white schools were well funded, but the all-black schools Walker attended were forced to rely on bake sales and hand-me-down books to make ends meet. There was no gymnasium, no football stadium, and no marching band.

“The black schools were obviously inferior,” Walker says. “We seldom saw white faces in school because the district administrators had little hands-on contact with students. Black teachers had to go to the central office to voice any complaints. It had been done that way for so long few people really said anything about it — it was a fait accompli.”

While Hope’s black school system lacked funding and support from the white community, it had the devoted backing of strong-willed black educators and energetic students. Henry Clay Yerger started the first black one-room school in 1886 and developed it into a 12-grade program with more than 900 students, offering courses in everything from Latin to agriculture. As the first training school for blacks west of the Mississippi, Yerger’s creation attracted students from all over Arkansas.

“We had a little different sense of pride than some of the places that didn’t have the accomplishments we had,” says Walker, whose grandparents taught in the black system. “People came from miles around to go to Yerger High School.”

Most black students were inspired to excel, and the school system provided the only opportunity. “We just wanted to rise, and education was the only way for us to rise,” says 72-year-old Electa Wiley, who graduated from the black system to a career in teaching. “Nearly everybody in my class left here and went on to do something with their lives.”

The black schools went beyond academic training. A family atmosphere prevailed at the schools that was never duplicated when the system integrated. “They instilled in us an attitude that if my brother was in trouble then I was too,” says Rosie Davis, who graduated from Yerger High in 1953. “Teachers weren’t afraid to give you that pat or hug. They weren’t afraid to touch you. Somehow this was lost.”

Class Unity

Walker brought his customary aggressiveness and legal skill to bear on the Hope case. Rather than fighting a narrow legal battle to get Davis the job she had been promised, Walker went to court on behalf of 80 parents, students, and teachers who filed a class-action suit against the Hope School District for widespread discrimination.

“This was the first time to my knowledge that an action was led in the South by black school teachers seeking to improve the lot of everyone,” Walker says. “The plaintiffs were poor, well-to-do, employed, and unemployed. All of them came together for this effort, they stayed together, and they found success.”

The first victory came when the all-white school board agreed to establish eight single-member districts for school board seats. Three of the districts would have black majorities and the remaining five would be predominantly white. The other charges in the lawsuit were put on hold until a new school board could be elected.

The politics of race seemed to dictate the outcome: a school board with five whites and three blacks. But the first election, held in June 1989, yielded an unexpected result. Black candidate Earnest Brown Sr. won in a largely rural district where nearly 60 percent of the voters were white. The other contests broke down along racial lines, giving the Hope School Board four whites and four blacks.

Walker was encouraged by Brown’s victory. “He won in an area where blacks and poor whites have traditionally gotten along well together,” he says. “They had something in common with each other and some respect for one another. They determined who would represent them based on something other than race, which is just what you hope for in a democracy.”

But race was far from a forgotten issue among the newly elected school board members. One of their first tasks — selecting a new superintendent — ended in a standoff, with the four black members supporting a black candidate and the white members backing a white applicant. Black board member Viney Johnson described the debate over the new superintendent as “heated.” Board president Ed Darling accused black members of playing politics to eliminate white candidates.

Ironically, it was Earnest Brown, the black board member from a white-majority district, who broke the deadlock by throwing his vote behind the white candidate, Jimmy Johnson. Walker tried to block the appointment in court, but his request for an injunction was rejected.

“In the beginning there was some mistrust because neither the white members nor the black members knew what I was going to do,” Johnson says. “But I’ve always believed if you treat people consistently and fairly, your race doesn’t matter. There was a period when trust had to develop between the board and myself and I think it’s developed.”

Winter Break

After the election, the new board worked to settle the remaining points of the original lawsuit. Finally, after months of negotiations, the case was settled out of court in December 1989. Although the school district admitted no wrongdoing, it pledged to remedy any past discrimination and prevent it from happening in the future.

The settlement required the board to take immediate steps to hire more black teachers and administrators — in effect, to recreate the family atmosphere that was so lacking for black students in the integrated system. The hiring agreement provided the first tangible evidence that the district was committed to placing blacks in leadership roles, giving students living examples of change standing at the front of the classroom.

“After integration, the black students were thrown into a completely different environment, and as a result they felt threatened,” Rosie Davis says. “The settlement will eventually give them more people to turn to in the schools.”

A black administrator, Kenneth Muldrew, was named to the newly created position of assistant superintendent. Although Rosie Davis wasn’t given a job as principal, she became the director of federal programs for the district. Angela Pigee was recently hired as an elementary school principal, becoming the first black woman since Davis to hold the post.

“We’re making inroads in an area that needed to be addressed,” Superintendent Johnson says. “Kenneth Muldrew’s number one priority is to recruit qualified black faculty members. He travels to college fairs all over the South to find recent graduates.”

The settlement also mandated racial sensitivity workshops for teachers, and eliminated the policy of offering three types of diplomas — vocational, basic, and college preparatory. Honors and advanced courses were opened to all students who could maintain passing grades, eliminating the previous system where admission was based on test scores and teacher recommendations.

A grievance procedure was also established to allow parents to contest disciplinary actions against their children. Although only three cases have actually come before the board since the settlement, black parents say they welcome the option.

“Some of the cases would never have been brought up in the past because it wouldn’t have done any good,” says Viney Johnson, a black board member. “Black students know that if they are mistreated, then something can be done about it.”

Students seem to agree. “I really don’t look at it as a black-and-white issue,” says Michael Carter, who became Hope High’s first black drum major this fall. “But the board’s there to help if we need it.”

“Everybody deserves a chance to teach or be on the school board,” agrees Quinton Radford, a 16-year-old Hope High School senior and former student council vice president. “Now, whoever is best for the job has the chance to get the job, and the different cultures have a better chance to speak with one another.”

Graduation

Nearly two years after voters elected a bi-racial school board, its members seem to have risen above much of their early racial antagonism. Because the single-member election system virtually ensures a racially mixed board, the new members came to realize that continued divisions between blacks and whites would render them ineffective.

“It takes time to build teamwork effectively,” Board President Ed Darling says. “We were kind of like eight people thrown out to plug the dike. There were some things said in the beginning on both sides that may have been racially motivated, but I think that’s all behind us.”

Hope High School Principal Michael Brown agrees. “There was really no one there to guide them so it took time to get adjusted,” he says from his cluttered office on the ground floor of the sprawling brick high school. “A confidence has to develop within the board and the administration. We have it now, but it took a while to happen.”

One of the clearest indications that the racial tensions are easing came last September. After heavy lobbying by a united school board, voters approved the first local property tax increase in more than 35 years for the construction of a new elementary school. The new building will house 1,500 students from kindergarten through fourth grade.

“I’d like to think that was the town’s way of saying, ‘OK, this is a new beginning and let’s start supporting the new school board,’” says Superintendent Jimmy Jones. “It shows we’re settling into a strong school system.”

Tags

Gordon Young

Gordon Young is a reporter for Spectrum Weekly in Little Rock. (1991)