Chipping In for Kids

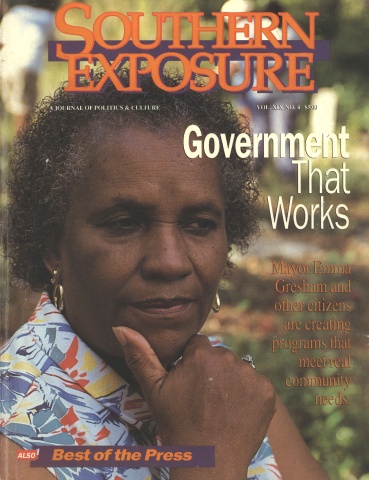

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Roanoke, Va. — “I’m 27,” Elizabeth Guthrie says. “Twenty-seven. Feel 97. I feel like I’m just the oldest woman in the hills.”

Guthrie gave birth to her twins, Casey and Cody, a year and a half ago. Born three months premature with weakened lungs and hearts, they spent most of their first few weeks in intensive care. With three other children at her apartment at Jamestown Place housing project, Guthrie found it almost impossible to get back and forth to Roanoke Memorial Hospital each day to be with the twins. She was overwhelmed.

But CHIP, the Roanoke Valley’s innovative medical program for children, began picking her up in its van and taking her to the hospital. CHIP arranged a meeting to give hospital workers an idea of her problems and to help Guthrie understand her babies’ ailments.

After the twins came home, a CHIP nurse and outreach worker helped Guthrie get them into an infant-stimulation program to make up for their slow development. Now CHIP is working with her as she appeals their cutoff from Medicaid. Cody and Casey still weigh just 18 pounds each, but their health is improving.

But CHIP didn’t stop with providing medical care. Nurses and outreach workers from the agency also helped Guthrie break away from a violent husband who has a criminal record and alcohol and drug problems.

Guthrie says he’s beaten her, trashed her apartment, and run over her with her car. Last fall, with the support of an outreach worker from CHIP, she went to court to get a judge’s order protecting her from her husband.

Now, she says, he is sober, has a job, and is treating her better. She hasn’t decided whether to take him back, she says, but she feels stronger and more confident.

Crossing Lines

Guthrie’s story shows what CHIP is all about — blending medical care and social work to help poor families grow up healthy. “They’re one of the few programs I’ve been involved with where they treated you as a person,” she says. “They don’t make you feel you’ve done something terrible when you’re asking them for help.”

CHIP — the Comprehensive Health Investment Project — serves nearly 900 poor children in the Roanoke Valley, from newborns to age eight. It does it all on a budget of about $800,000 a year, pieced together from state and local funding, foundation grants, and donations from local businesses.

Since its creation three years ago, CHIP has attracted nationwide attention, winning awards for innovative health care from the National Association of Counties and the National Association of County Health Officials. The program works because it defies traditional models for health and social services — both in the way it’s funded and in the way it operates at the grassroots.

It has grown and prospered financially partly because it hasn’t depended solely on the federal and state governments for funding. Instead, it operates as a cooperative developed by private doctors, local health departments, area businesses, and the local community action agency, Total Action Against Poverty.

CHIP is anchored in the Roanoke city and Allegheny regional health departments and receives some state funding. But in Virginia — the 12th richest state in the nation but one of the stingiest when it comes to paying for social services — CHIP has also been forced to look elsewhere for money.

It has earned support from local businesses, which have donated office equipment, passenger vans, and other help. State and national charitable foundations have also backed the program. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, one of the nation’s largest, has awarded CHIP $3.8 million.

The money has allowed CHIP to expand beyond the bare-bones operations that have characterized most social programs since the federal government surrendered its War on Poverty. With its broad base of support, CHIP has even managed to grow in the midst of the recent stage budget turmoil in Virginia.

Kids First

Just as it goes beyond traditional models of funding, CHIP also violates the standard procedures that make many social service programs a bureaucratic nightmare for families that are struggling to survive. CHIP workers cross the normal lines of responsibility that usually fence off different social programs — and send poor people from office to office looking for help.

They rarely tell anyone: “Sorry, it’s not my job.” Instead, they give poor families whatever help is necessary, and serve as advocates in cutting red tape and forcing action from other agencies. This holistic approach includes helping a mother and child find better housing, taking them a box of canned goods from a food pantry, and operating a “lending library” of toys that they can borrow. It also includes empowering parents by helping them learn how to read.

One 23-year-old mother earned her high-school equivalency diploma at the urging of CHIP workers, and has now been accepted into nursing school. Her CHIP workers said it took some gentle pushing at first, but from there she took off.

“I made a commitment to myself to accomplish something besides working in a fast-food joint,” said the mother, who is so shy she didn’t want her name used. “I’m proud of myself. I want the kids to be proud of me too.”

CHIP nurses and outreach workers are paired into seven teams. Case loads for each team run about 140 children; CHIP officials admit that is too many but say they hope to cut down those numbers as the staff grows.

Linda Lamm, who lives in a subsidized apartment complex in Roanoke, says the visiting nurses and outreach workers from CHIP have made a big difference for her three-year-old daughter. Clarissa, who suffers from a hyperactive condition known as attention deficit disorder, often attacks her one-year-old brother Kenny. She pulls his hair, bites him, pushes him.

“It’s not every once in a while,” Lamm says. “It’s an everyday thing, four to six times a day. It really bothers me, nerve-wise. I’m a very nervous person anyway.”

Thanks to CHIP, Lamm says, Clarissa is on new medication and starting to improve. “CHIP is wonderful. I think the United States should really focus on our American children’s health. Giving money overseas, Russia and stuff, that’s fine. But we’ve got to take care of our kids first.”

Out of the E.R.

America hasn’t been doing a very good job of taking care of its kids. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, one-third of low-income children lack proper immunization for measles or mumps; 1 in 10 children under four have not seen a doctor in the past year.

Meanwhile, fewer pediatricians across the nation are willing to treat Medicaid patients because of red tape and low government payments, according to a study published by the academy in June. The study found that the proportion of pediatricians who saw no Medicaid patients grew from 15 percent to 23 percent in the past decade, and the proportion who limited the number they saw increased from 26 percent to 39 percent.

The problem was even worse four years ago in the Roanoke Valley. Only one of the 21 pediatricians in the area was willing to see new Medicaid patients, and 42 percent of the people who qualified for Medicaid in Roanoke weren’t using it.

Dr. Douglas Pierce had those facts on his mind in 1987 when he read in the newspaper that Cabell Brand, a Salem businessman and president of Roanoke’s community action agency, Total Action Against Poverty, had been named chairman of the Virginia Board of Health.

Pierce, who had treated Brand’s children, picked up the phone and called him. From there, CHIP was born. Total Action Against Poverty helped write the proposal that drew in seed money from the state. From an initial pilot group of 100 children, the program grew.

Today, 33 pediatricians and family doctors and seven dentists participate. CHIP nurses and outreach workers fill out the Medicaid paperwork, make sure that patients keep appointments, and help them fill prescriptions. Super X Drug Store provides discount prescriptions to CHIP children.

Despite its success, organizers say the program is a long way from reaching all the children who need it. So far CHIP has enough money to reach only one in five of all eligible children in the Roanoke Valley. A family of four qualifies for the program if it has a yearly income below $17,823.

For many working poor families, who earn too much money to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to buy health insurance, CHIP provides their first chance at a regular pediatrician. If they got medical help at all before, it was through walk-in visits to emergency rooms. A study last year at Roanoke Memorial Hospital found that fewer than 15 percent of children’s emergency-room visits on the evening shift were true emergencies.

When families are forced to use emergency rooms for regular care, the doctors on duty do not know the children and have no medical histories on them. So, to play catch-up medicine and to protect themselves, the doctors run expensive background tests. That runs up huge bills the families can’t pay. So they go to another emergency room the next time their children get sick — or nowhere at all.

That’s the way things were a few years ago for Gerald and Roberta McCraw and their five children. The McCraws, who live at Lansdowne Park public housing complex, couldn’t afford insurance, and they had a stack of unpaid hospital bills.

CHIP gave them something they’d never had: their own doctor.

It was almost too good to believe, Roberta McCraw told an Associated Press reporter last fall. “The baby was fussing and running a fever and I was scared to death. I had never called my doctor at night and didn’t know whether I should maybe just go ahead and go to the emergency room. But I called, and he said bring her in.

“He examined her and looked at her record and in a minute said, ‘Mrs. McCraw, Amanda’s teething. Take her home, she’ll be just fine.’ And she was.”

It’s a story that Cabell Brand and other CHIP founders would like to see repeated across the nation. More than $2.4 million of the money CHIP received from the Kellogg Foundation is for replicating the program across Virginia, starting in Abingdon, Charlottesville, Richmond, and Chesapeake. From there, Brand says, “There’s no reason for it to stop at the state line.”

Bright Sunshine

Again and again, CHIP’S outreach workers cross the line that has been set down in traditional welfare programs: Don’t get personally involved.

Gloria Charlton, an outreach worker, talks on the phone every day with one CHIP mother who needs daily support. Some of her problems might not seem like a big deal to some people, but “they’re a crisis to her.”

“Whenever they call you, whatever they tell you, you have to know it’s the most important thing, the most awful thing in the world to them at that time,” Charlton says. But “sometimes you have to ask yourself if you’re really helping them if you do everything for them.”

The key, she says, is doing what needs to be done to build up their confidence and help them gain the skills they need to be more self-reliant. When they start to succeed, Charlton doesn’t just tell them: “I’m proud of you.” She tells them, “You should be proud of yourself.”

One CHIP kid was born with severe birth defects and spent two months in the hospital getting reconstructive surgery. The baby has potentially life-threatening asthma, so CHIP helped the mother get a phone to use in emergencies.

In April, the mother got a phone bill for $600 worth of 900-number phone calls. Her CHIP nurse, Pat Gayle, did some checking; it turned out that all the calls had been made on two days when the mother and child had been at the hospital.

The mother has a speech defect, so Gayle spent two hours one afternoon in conference calls with her and MCI and AT&T officials before she was finally able to persuade them to drop the 900- number charges. The mother ended up paying only her $30 bill — and kept her phone.

Sometimes, what a child needs is as simple as a change of scenery. Darlene Brown, a former CHIP outreach worker, remembers working with one three-year-old girl whose slow development made it difficult for her to speak clearly.

Her family’s home was dark and dingy, and she had never been to a park. Brown took her — and the effect was dramatic.

“Just being out in the bright sunshine, she really started talking,” Brown recalls. “She started saying things I didn’t know she knew how to say.”

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)