This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

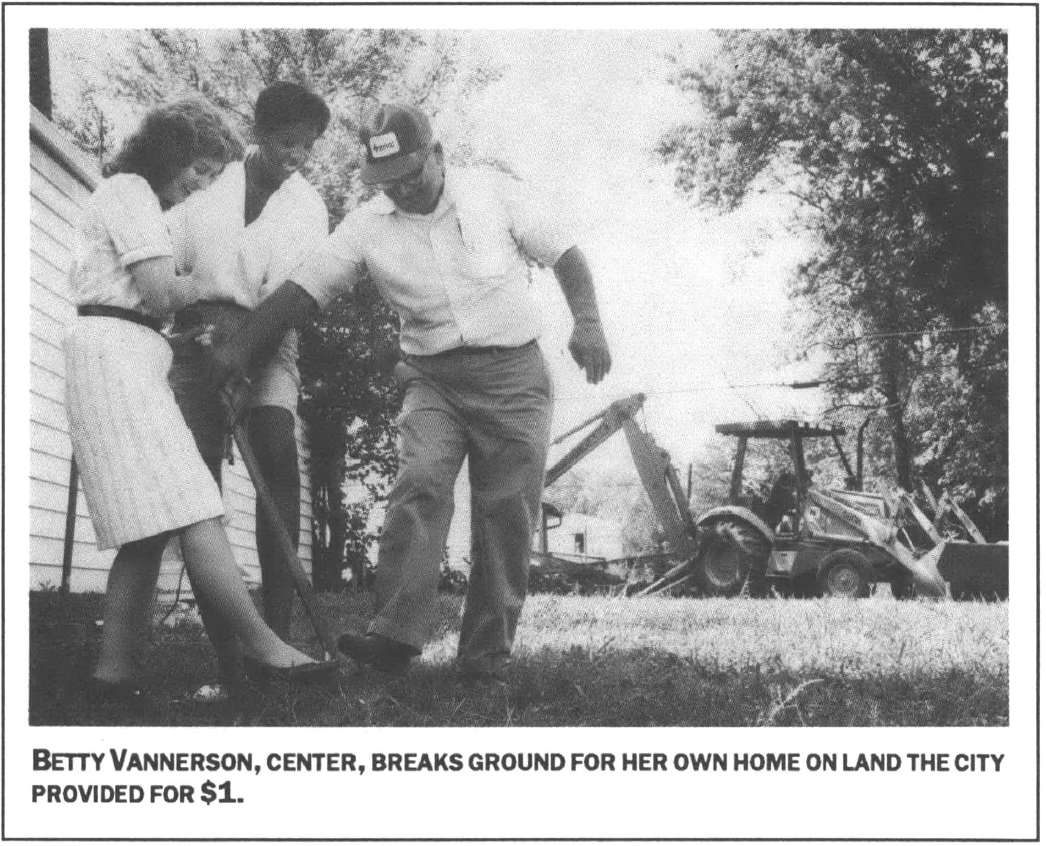

Louisville, Ky. — In a vacant lot that was once home to a huge, abandoned Victorian house, Betty Vannerson takes hold of a shovel and digs into the earth. White lines drawn with flour on green grass mark the place where a small three-bedroom house will soon stand. Vannerson, a 39-year-old cook with three children, is breaking ground for her own home in the West End neighborhood of Russell.

A prosperous black community in the early part of the century, Russell has fallen on hard times in the past few decades. More than half its residents live in poverty, and its streets are dotted with boarded-up houses and empty lots.

But as Vannerson smiles for photographers and surveys her new neighborhood, she can see signs of revitalization. Across Magazine Street, three new houses with neat white trim stand in a row, separated by narrow strips of well-tended lawn. Another new house stands just around the comer, and plans are under way for more new houses on two vacant lots next door.

“I’m very excited,” Vannerson tells reporters covering the groundbreaking. “This is a dream come true for me and my kids. I always wanted to buy a house, but I thought it would be above my means. I’ve been renting since I was 22. The difference will be that I won’t have somebody monitoring my life.”

Like the other new homes on the block, Vannerson’s is being built by volunteers from Habitat for Humanity, a nationwide group that helps construct affordable housing for low-income families. Becoming a homeowner will cost Vannerson only $25,000, and her monthly mortgage payments of $180 will be less than the $277 she now pays in rent.

How can Habitat afford to build the house so inexpensively? One reason: It bought the lot for $1 from the Louisville and Jefferson County Land Bank Authority, an innovative new program that buys up abandoned properties and turns them over to non-profit developers who build low-income housing.

The Land Bank — a joint venture by the city, county, state, and school board — erases all back taxes on abandoned lots and sells them to developers like Habitat for $1. The tax savings and giveaway prices make it easier for non-profits to build homes for people who might otherwise be priced out of the housing market.

“One of the great challenges of trying to build affordable housing is to keep the costs down,” says Mike Jupin, executive director of South Louisville Community Ministries. “If we can acquire a piece of land for $1, it means it’ll cost less to the person we sell it to. The Land Bank makes it more economically feasible to provide housing at the lowest possible cost.”

Trash and Taxes

The need for a land bank in Louisville has been painfully apparent for decades. The city is home to an estimated 7,000 abandoned lots, many of them choked by weeds and trash. At the same time, more than 2,000 people currently crowd the waiting list for public housing.

The Land Bank offers a disarmingly simple solution to both problems. The program helps the city and county by rejuvenating vacant lots and generating taxes on delinquent properties. It also helps low-income families move out of public housing and into their own homes, freeing up space for the homeless.

“It’s a terrific tool,” says David Fleischaker, a consultant with Louisville Housing Services, a city agency that plans to build low-income housing on Land Bank property. “Like the mousetrap, a lot of ideas seem obvious after they’re implemented, but somehow they weren’t. The Land Bank is probably one of those. I don’t see how it can’t catch on elsewhere.”

Although the Land Bank is less than a year old, other cities across Kentucky are already moving to create similar programs. Louisville has received calls about its Land Bank from Florida, Michigan, California, and Pennsylvania.

The Louisville Land Bank got its start back in 1988, when legislators from the city prompted the Kentucky General Assembly to pass a law allowing the creation of land banks. The city, county, school board, and state promptly signed an agreement creating the Land Bank Authority, but the program didn’t really get off the ground until 1990, when the legislature amended the law and ironed out some of its technical problems.

The law requires the Land Bank to have four directors — one each from the city, county, state, and school board. The Bank goes to court to buy up tax-delinquent lots and then sells them, dividing the revenues among the four participating governments in proportion to the taxes each was owed. Non-profits can buy lots for $1, but private owners must pay the full price the Land Bank paid for the lot plus 20 percent of its assessed value.

Officials say they are thrilled with the way the Land Bank takes abandoned lots that cost the city money to maintain and turns them into tax-generating properties. “We get calls about the grass not being cut and trash piling up,” explains Jim Allen, director of city housing and urban development. “We go out and maintain the property and send bills to the owners that never get paid. If we can get a property cleaned up and get a house on it, it’s a double hit for us. It’s producing taxes and it’s not costing the city time and money to maintain it.”

$11 a Month

Leaders of non-profit organizations struggling to build affordable housing say they are equally thrilled by the success of the Land Bank. Sitting on a low cement wall bordering a vacant comer lot that is the first piece of property Louisville Housing Services has bought from the Land Bank, David Fleischaker whips out his calculator to figure out what it will cost families to buy the houses that will be built here. “This is just a gleam in our eyes right now,” he says, “but in terms of numbers, I can say that with the Land Bank you can do development for a lot less.”

At most, Fleischaker calculates, it will cost $49,000 to build a 1,100-square-foot house with three bedrooms and one and a half baths. Assuming a mortgage with city-backed interest rates of eight percent, monthly payments will run about $440. To qualify for such a loan, a family must earn at least $1,570 per month — $18,857 a year — and can’t have more than $125 in other monthly fixed expenses such as car payments and education costs.

If Louisville Housing Services had paid $1,500 in taxes on the lot instead of getting it from the Land Bank for a dollar, Fleischaker points out, it would have been forced to add $11 to a family’s monthly payment. “That would mean they need to make $500 more per year to qualify for a loan. That may not sound like a lot, but in that income range, there’s a lot of people who can just barely afford it and to whom $11 a month makes a big difference.”

Squinting into the sun, Fleischaker looks across the street at the renovation under way on a dilapidated building that appears to have had past lives as a church, a bar, and an apartment building. Then he glances down the street in the other direction, taking in a well-maintained brick house. “This will be a very nice comer,” he says.

At the rate the Land Bank is buying up land, other corners should be quick to follow. The Bank has already acquired close to 600 lots, thanks to a mass foreclosure law which allows the city to lump tax-delinquent properties together and file suit against them in circuit court all at once. As a result, the city forecloses on approximately 20 properties each month. The Land Bank bids on those lots at court sales, and usually gets them all.

In fact, the Land Bank is buying up properties faster than it can sell them. “The non-profits have limited resources and staff, and they simply cannot redevelop that many properties a year,” says Fred Nett, city administrator of acquisitions and foreclosures. So far, the Land Bank has sold only 50 properties.

In many cases, Nett says, the Land Bank buys properties with the intention of hanging on to them for a while. Many inner-city lots have only 25 feet of frontage. Because fire codes require five feet on either side of a house, homes built on such lots could be no more than 15 feet wide. To provide more space, the Land Bank gradually collects several tracts in one area, assembling larger lots that will be more attractive to developers.

The American Dream

Not far from Churchill Downs, Mike Jupin of South Louisville Community Ministries walks down a run-down street. To his left is nothing but a small playground, a pink, boarded-up shotgun house, and an overgrown tangle of brush. To his right a large vacant lot splits the block in two.

Jupin can picture a cluster of homes here, a vibrant, rebuilt community. He knows exactly how the houses will look: energy-efficient, low-maintenance, and vinyl-sided. And he knows who will live in them: low-income, first-time homeowners.

The Land Bank owns several vacant lots on both sides of the block, and the Community Ministries wants to build four or five two-story, two-bedroom houses on them. The group, which provides emergency assistance to help people pay for rent and utilities, got interested in building low-income houses because homeowners in South Louisville are resistant to additional public housing. The area is already home to the 750-unit Iroquois Homes, the largest housing project in Kentucky, and two private, low-income apartment complexes totaling 800 units.

Jupin says the Ministries plans to sell houses on the Land Bank lots to people now living in public housing who make between $16,000 and $20,000 a year. “Hopefully we’re helping them buy part of the American Dream — their own home,” he says. “I think it’s been shown that if you own your own home you have more of a stake in the community. That will open up public housing for people at the bottom of the rung right now — people who need to stabilize their lives and work towards a job or an education and get to the point where they can buy a house.”

The Ministries came up with its plan for building houses near the Downs only after the Land Bank offered to sell the lots for $1, free of back taxes. “Without the Land Bank, we probably would not pursue this,” Jupin says. “We do not have the resources to track down the owners of vacant properties and go through the courts. We’d wind up with lots of blight in the neighborhood, broken windows, and weeds.”

While housing advocates applaud the Land Bank for reaching out to local groups like the Ministries, some caution that the program is still young and has the potential to go astray. Jack Trawick, director of the Louisville Design Center, a non-profit organization that provides technical assistance to neighborhood groups, worries that the Land Bank may be tempted to package small lots into larger tracts for big developers.

“The Land Bank certainly could be a very helpful and powerful tool, but it remains to be seen how neighborhood-sensitive it is and how closely it works with community-based organizations,” Trawick says.

City officials say neighborhood-based non-profits can buy as much Land Bank property as they want — but that there has not been much competition for the lots so far. “They’re not in heavy demand,” says Fred Nett, city administrator of foreclosures.

Still, Trawick and other housing advocates say the success of the Land Bank will ultimately depend on planning. “The question is, what’s their strategy for unloading these things? Is it random, catch-as-catch-can, or more deliberate? I think there is more and more of a push coming from neighborhood organizations and housing advocates for comprehensive planning that uses things like the Land Bank. A lot will depend on the next year. I am hopeful that the community groups and the city will develop a constructive dialogue on how to make the Land Bank work for everyone.”

In the meantime, non-profit groups like Habitat for Humanity continue to buy Land Bank properties and build homes for working families like Betty Vannerson’s. Diane Kirkpatrick, executive director of Habitat, says the group hopes to build 40 houses in the Russell neighborhood in the next five years.

In the past, Kirkpatrick says, Habitat has had to pay as much as $800 in back taxes on lots it bought. The Land Bank has helped make affordable housing more affordable.

“If we can buy 40 pieces of land for $40, that obviously frees up a tremendous amount of money for construction,” she says. “The more money we save, the more houses we can build.”

Tags

Robin Epstein

Robin Epstein is a freelance writer in Louisville. (1991)