Art for Hampton’s Sake

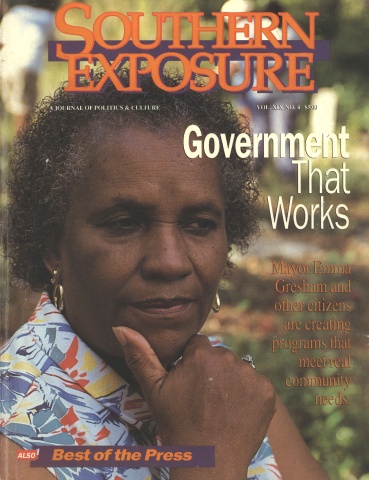

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 19 No. 4, "Government That Works." Find more from that issue here.

Hampton, Va. — You can stand on the sidewalk where Bridge Street crosses an inlet of the Hampton River, focus your eye on the egrets wading through the bay — and gaze into another era.

Here, at the edge of downtown, scurfy crabbing boats with nets piled high sit anchored in the river. Gulls swim alongside and fly overhead, hoping for an easy morsel from the day’ s catch. Along a hidden lane, two wholesale crab dealers advertise their goods in front of non-descript buildings. “Quality Crabmeat Since 1937” boasts the sign outside Lawson Seafood Company.

Indeed, this 380-year-old city is tied inextricably to its 63 miles of shoreline, and seafood has helped support thousands of its residents. But cast your visual net wider and a different Hampton emerges. Across the lane from the crab wholesalers rise the vaulted trusses of the brick-and-glass building that will soon house the Virginia Air and Space Museum and the Hampton Roads History Center. Across the street, in a landscaped brick plaza, children line up to ride an elegant 1920s carousel. Just down the block, visitors admire the diverse local artwork in the cooperatively run Blue Skies Gallery.

And in a restored brick building that punctuates the Victorian houses and crepe myrtles of nearby Victoria Boulevard, a small group of city employees plan the next stages in Hampton’s cultural revival. They work for the Hampton Arts Commission, one of the few local government agencies in the South charged with creating an environment in which the arts can flourish.

In four years, Hampton has gone from a city with few cultural opportunities to one with rich and diverse offerings. At a time when most governments are slashing funds for the arts — Governor Douglas Wilder referred to the arts as “niceties” and cut the state arts commission budget by 70 percent this year — Hampton has taken the opposite direction. “Our mission is to make Hampton the most livable city in the Commonwealth of Virginia,” says Mayor James Eason.

Not just livable for people who enjoy Verdi or Mozart. The commission has reached across lines of race, age, and class to make the arts accessible to a broad range of Hamptonians. For sure, it has presented the classical concerts and juried art shows that fuel most local arts councils. But it has also worked with inner-city teenagers, deaf schoolchildren, and African-American artists. A concert this fall by Guinea’s Les Ballets Africains drew the commission’s first sell-out crowd — and let the traditional arts establishment know that Hampton was ready for some cross-cultural excitement.

“I think the future of the arts is in ethnic programs that represent the essence of a culture,” says commission director Michael Curry. “We’ve got a global family — music, dance, the arts do cross all those lines and make us expand our awareness of working together.”

Dwarf Among Cities

Within the sprawling metropolitan area of southeastern Virginia known as Hampton Roads, the city of Hampton itself — population 130,000 — has long suffered from an inferiority complex.

Dwarfed by Norfolk, Virginia Beach, and Newport News, Hampton often gets lost amidst its better-known neighbors. Its greatest claim to fame lies in its history: City boosters promote Hampton as the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in the nation. Unfortunately, most of the historic structures have been torn down — first during the Civil War and more recently during “urban renewal” — giving Hampton the feel of a generic, medium-sized Southern city.

Hampton’s other source of pride has come from the aerospace industry. The original seven astronauts trained at the NASA Langley Research Center, a billion-dollar lab that helped send missions to Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Near the NASA center sits Langley Air Force Base, home of the U.S. Tactical Air Command.

Even though NASA and the military base have poured billions of dollars into the local economy, they have hardly brought prosperity. With an average personal income of $14,460 last year, Hampton ranked well below the state and regional average. Throughout the 1980s, economic development stood still. The city was losing industry to Newport News; it didn’t even have commercial sites to offer prospective businesses.

“If General Motors had knocked on our door and said they wanted to move their headquarters to Hampton, we couldn’t have accommodated them,” says Mayor Eason.

Just as the economy lagged, so did Hampton’s cultural life. In the late 1960s, a grassroots group called the Hampton Arts and Humanities Association sprang up, and did good work for about a decade. It provided music and art lessons for children and promoted archaeological research downtown — and it provided a model for biracial cooperation in a city that’s one-third black. “Black and white people really interacted and struggled for the same goal,” says Jeanne Zeidler, who worked at the association for several years.

But in the late 1970s, the city absorbed the association into its recreation department, and the group soon floundered. For a decade, Hampton had no coordinating arts group.

“There was no arts scene,” says Hampton native Nancy Bagley Adams, who now chairs the Hampton Arts Commission. “We had local artists that were fragmented, and people went to Norfolk.” Carol Conway, another native who runs the Blue Skies Gallery, remembers the city 10 years ago as a “vast wasteland.” The public schools had all but eliminated art education. The most thriving cultural scene took place at Hampton University, but the white community pretty much ignored the goings-on at the historically black institution.

It took the election of a mayor who made the connection between the stagnant economy and the ho-hum cultural life — and who saw the arts and humanities as a chance for the city to attract new jobs — to change all that. After defeating an anti-tax incumbent in 1982, James Eason immediately sponsored a series of citizen forums at public schools and a shopping mall. People turned out and talked about their vision for the city — and based on those comments, the City Council kicked off an intensive strategic planning process.

“We saw that there was a window of opportunity open, but that window would close in the late ’80s, and then there would be an economic downturn,” Eason says. “If we had to wait until the next upturn in the 1990s, it would be too late.”

So the council divided its goals into five broad areas: putting together attractive commercial sites, addressing the city’s tax structure, cleaning up Hampton’s appearance, upgrading the schools, and improving the quality of life.

In an unusual move, the mayor assigned an assistant city manager to focus her energies on improving Hampton’s cultural offerings and recreational facilities. As a result, since 1987, the city has built a new library and three new branches, an arts center, and a stadium. The Hampton Carousel, one of the 200 original tum-of-the-century carousels left in the United States, has been renovated and moved downtown. Construction on the $30 million waterfront museum — which city leaders expect will draw 300,000 visitors each year — will be completed next spring.

Most significantly, Eason established a protected fund — using cable franchise fees — dedicated solely to the arts. The fund raised $322,000 during the last budget year. Using that money, the mayor created the Hampton Arts Commission four years ago as a full-fledged department of city government and hired Virginia’s only full-time local arts director.

A Lost People

That director is Michael Curry, former director of the non-profit Fine Arts Foundation in Lafayette, Louisiana. A chain-smoking Englishman with a graying beard and a self-confidence that borders on cockiness, Curry attended a London boarding school and studied at the University of London before immigrating to Louisiana at the age of 22. At the time, Lafayette had almost no arts scene outside the indigenous Cajun culture; Places Rated Almanac once ranked the city dead last. Curry turned the city around during his 14 years there, bringing in such performers as Ella Fitzgerald and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

“We sat around before Michael was hired and said, ‘What are we going to do?’” recalls Adams, chair of the Hampton commission. “We were a lost group of people. And then Michael came in.”

Curry began by surveying existing arts groups to discover their needs. Besides the obvious one — money — most of the groups said they sorely needed publicity. So the commission began publishing Diversions, a bimonthly magazine that reaches 15,000 Hampton households. Then it launched a traditional concert series, starting with the Haydn Trio of Vienna. “I felt very strongly that we had to get the existing arts patrons behind us before we did anything,” Curry says.

Fifty-two people attended that first Haydn Concert, in a hall that seated 1,800. “I was bloody terrified,” Curry remembers. But he kept pushing — and he expanded the commission’s offerings beyond the traditional classical-music-for-middle-class-white-people fare.

Working with Hampton University, the commission sponsored a four-week workshop with master printmaker Ron Adams. Twenty-two high school and college students — black, white, and Asian — participated. The commission also curated an exhibit of works by the university faculty, the first time some of them had exhibited off-campus. It worked closely with the Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind, along with the Hampton school system, to give students a wider exposure to cultural events. And each year, the commission doles out money to a wide array of local arts groups.

Recently, Curry brought in Cantare Audire, a Namibian choir, during its first American tour. The first half of the concert was strictly classical — but then the choir broke out into drumming and grass-skirt dancing. “The audience was on their feet, screaming and dancing,” he recalls.

Much of the city-sponsored programming remains quite traditional — groups like the Orion String Quartet and the Hanover Band. Jeanne Zeidler, who has worked for grassroots arts organizations in Hampton since the early 1970s, says the Arts Commission is still struggling with the community’s competing needs. “What is going on now is an attempt to find a balance — to attract an audience that’s truly diverse, and still keep the people who had the advantage as children to go to concerts and travel to great museums,” says Zeidler, who now directs the Hampton University Museum.

“I don’t think all the solutions have been found, or even that all the questions are asked,” Zeidler continues. But she believes that Curry has taken important strides away from elitism. “Is he perfect? No. Is anybody? No. But I think he had a solid sense of direction. Besides that, he’s not afraid to take risks, which is sorely needed in this area.”

One of those risks has been locating the Great Performers Series across the river from downtown, at Hampton University. Despite its magnificent waterfront campus, the university still scares away some white Hamptonians who never set foot on that side of town. “The collaboration between the city and the university has never been so strong, and that is still a risk,” Zeidler says.

The Tailback

For all of Curry’s successes, the real inspiration for Hampton’s cultural renaissance comes from a native Hamptonian — a former high-school tailback who grew up to be mayor.

In James Eason’s childhood home, Hampton affairs were paramount. His father coached football for 20 years at the city’s only white high school before going on to become Hampton’s first recreation director. “The thing we talked about at home was the city,” recalls Eason, who looks like a cross between an accountant (which he is) and a teddy bear (which his friends say he also is). “The environment in which I grew up was a very pro-Hampton, loyal environment. When Hampton High School played, it was almost like the city competing against the other cities.”

Eason left his hometown to play football for the University of North Carolina. But he returned immediately after graduating in 1965 — and 13 years later he won an appointment to the local school board.

The appointment turned out to be a mixed blessing. The Proposition 13 anti-tax movement was spreading eastward from California, and it hit Virginia with full force. Just as Eason was taking a leadership role on the school board, Hampton elected its first and only anti-tax mayor and City Council majority.

“It reached a point in the spring of 1981 that the council sought to really decimate the school budget,” Eason says. As vice-chair of the school board, he had to defend the city’s educational system — and he did so at a meeting that got so crowded that it had to be moved to the coliseum.

But the anti-tax majority prevailed that year. The city began closing schools, laying off teachers — and using Hampton’s economic problems as an excuse. “The mayor at the time said Hampton is a declining city; we can’t afford these educational programs. We are a declining city. That hit me on the head like a two-by-four. That sent shivers up my spine.” Enraged, Eason challenged the incumbent during the 1982 elections — and won by a more than two-to-one margin.

Eason’s belief in the importance of the arts came later, as the city developed its long-term strategic plan. The new mayor began to see a richer cultural environment as the way to attract industry — and to create a workforce that appreciates diversity.

“One thing that has influenced me is to look at who will be your workforce in the year 2000,” he says. With only 15 percent of the new jobs going to white men, “we’re going to be sitting here with the greatest diversification of the workforce in America’s history.

“What’s going to be necessary is molding the workforce into a team. You as a white male have got to appreciate what is motivating the black female or the Hispanic. You can’t just snap your fingers and say, ‘You — appreciate diversity.’ In the arts program, the main lesson is the appreciation of differences.”

The second lesson, of course, is creativity. “Art encourages the expansion of the mind,” Eason says. “If the city has created an environment that encourages expression and risk-taking, who is going to say that there will not be a spillover into somebody who sits down with a computer to program? Because that person was encouraged to be expressive without the fear of ridicule — Lord knows what happens from a creative standpoint.”

The biggest monument to Hampton’s cultural revival will be the waterfront museum, a 110,000-square-foot building with air-and-space artifacts as well as historic exhibits. City literature promotes the museum as a tourist draw, but Eason sees it as a way to educate Hampton’s own citizens — particularly children. When the mayor’s conversations wander afield, they often touch on his hopes for children and his fears that the next generation is growing up at a perilous time.

Perhaps that explains why Eason takes so much pride in the recent work the city of Hampton has done in the school system, expanding elementary-school art programs at a time when Virginia schools face across-the-board cuts. The city has sent artists into the public schools, and the Arts Commission has exhibited work by artists on the faculties of the city schools.

His concern for children also explains why Eason beams when he talks about the restored carousel, which operates in a glass pavilion overlooking a landscaped plaza. Made by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company more than 70 years ago, its 48 sad-eyed horses and two chariots were hand-carved by German, Russian, and Italian immigrants. The carousel reopened last summer — and on weekend days, more than 1,000 children come downtown to ride.

Of course, the carousel is dwarfed by the Air and Space Museum. But, says assistant city manager Elizabeth Walker, “I think the carousel meant as much to the mayor as the $30 million project next door.”

Beyond Brick and Mortar

In late October, the British-based Lucas Industries announced it would locate the world headquarters of one of its divisions to Hampton. The conglomerate, which manufactures automobile parts and aerospace equipment, will generate 400 jobs at first and more than 1,000 later on. It will also pay more than $175,000 in annual real-estate taxes. Eason calls Lucas’ decision “the biggest hit that Hampton has ever had.”

City officials cite the industrial recruitment as an example of Hampton’s cultural strategy paying off. At the same time, attracting international corporations comprises only one form of economic development. Eason continues to work on downtown revitalization. He wants to build a performing-arts center in the central business district, which will attract more nighttime traffic. Restaurants should follow, along with other late-night businesses.

What’s more, the city is now working to create a Santa Fe-style arts district that would include artist studios, galleries, and other art-related businesses in the Victorian houses lining two downtown streets. The city has already attracted the cooperative Blue Skies Gallery to a commercial building in the central business district, and gallery manager Carol Conway looks forward to moving into one of the grand old homes along Victoria Boulevard and Armistead Avenue.

City planners are continuing to do the research that will enable the city to create the district. But even without that district, Conway sees a tangible difference in downtown’s vibrancy over the past few years. The carousel has drawn people back to the inner city, and those families come to visit — and shop — at Blue Skies. At this rate, she says, it won’t be long before downtown becomes a mecca where people come to browse galleries, dance at street festivals, watch theater productions, eat at restaurants, and just take in the passing scene.

“Hampton’s making more of a commitment, both in a financial and physical way,” she says. “Before Michael Curry was hired, downtown was just involved with brick and mortar — the tearing down of buildings

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)